This document provides an overview of a course on digital electronics that covers combinational and sequential logic. The course consists of 11 lectures and 6 hardware lab workshops. The objectives are for students to learn about combinational and sequential logic circuits, how digital logic gates are built using transistors, and how to design and construct simple digital electronic systems. Key topics that will be covered include Boolean algebra, logic gates, combinational logic, sequential logic, and how digital systems are constructed from semiconductors to computers. Recommended textbooks are also listed.

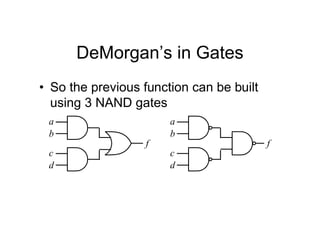

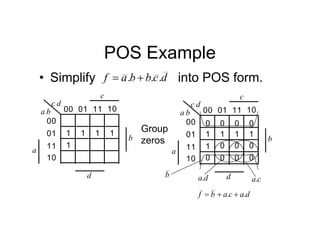

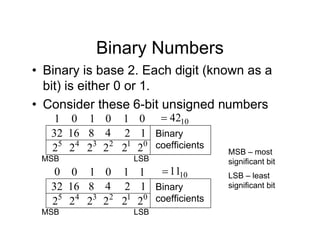

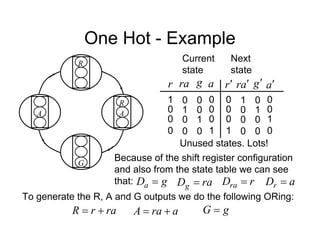

![Tripos Example

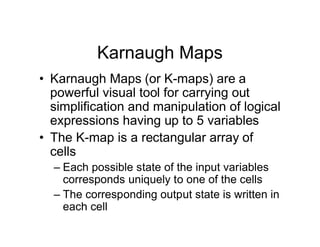

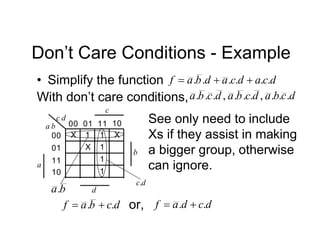

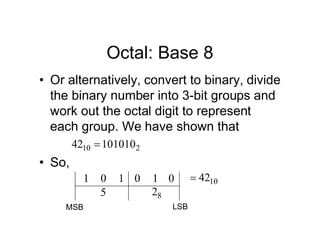

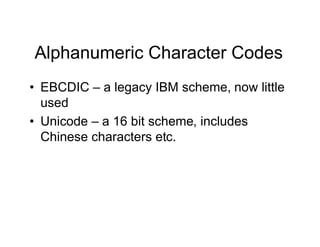

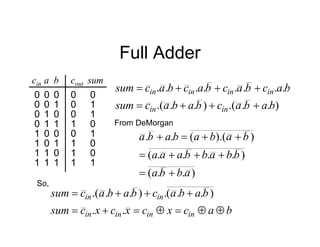

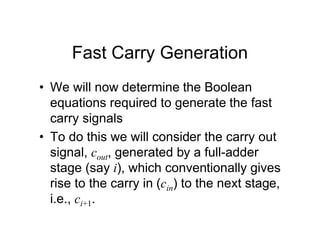

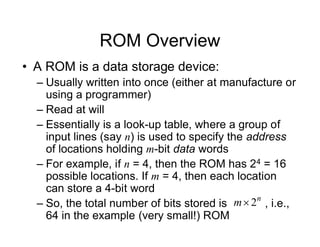

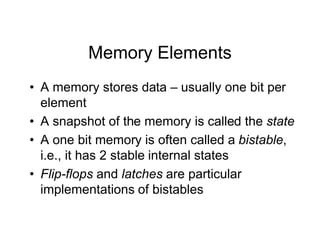

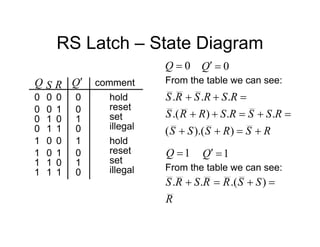

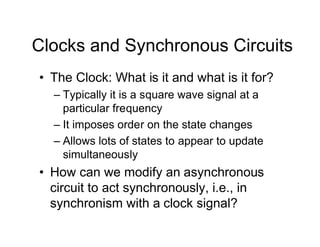

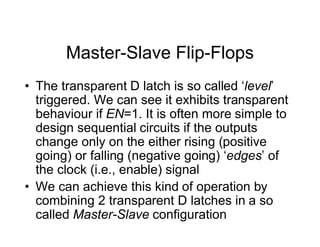

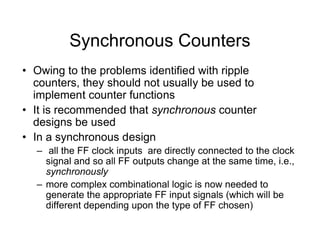

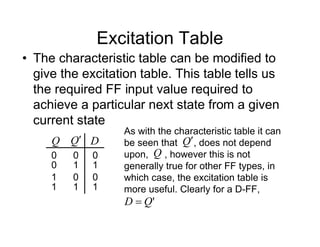

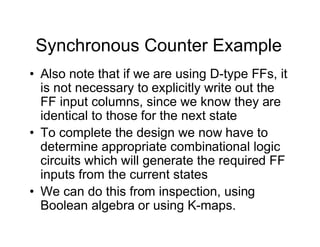

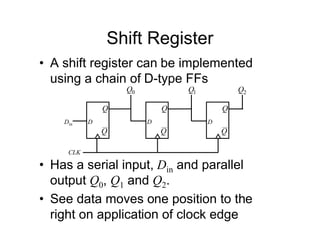

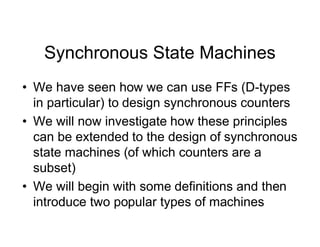

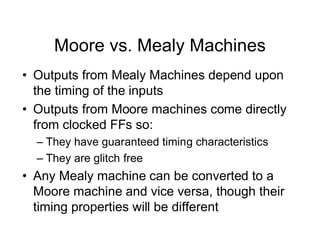

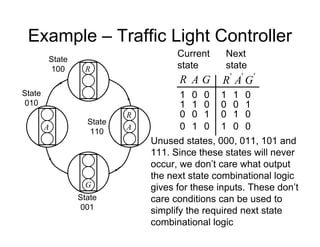

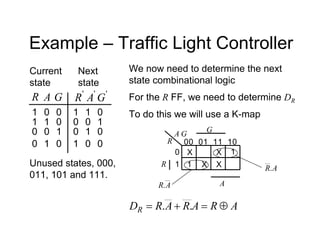

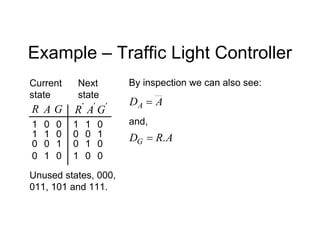

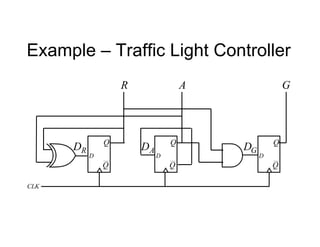

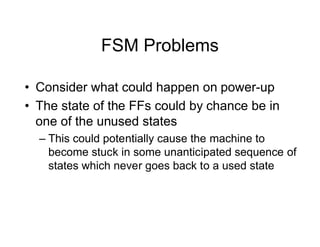

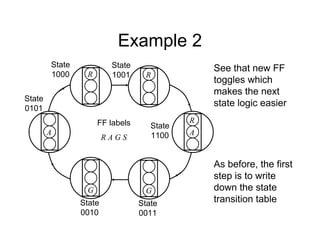

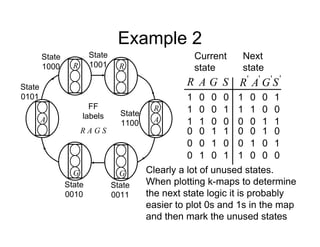

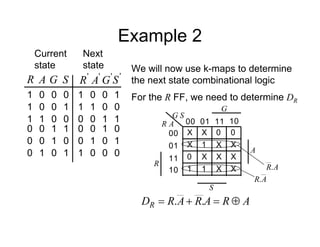

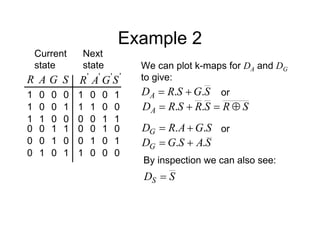

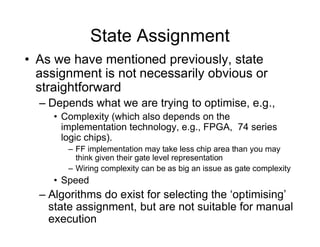

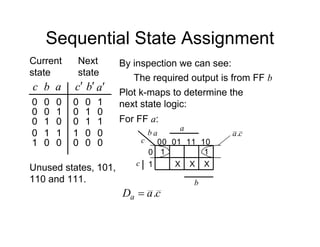

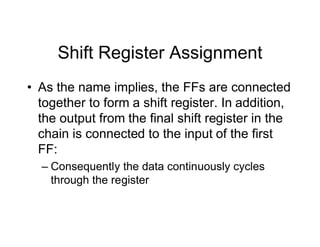

• The state diagram for a synchroniser is shown.

It has 3 states and 2 inputs, namely e and r.

The states are mapped using sequential

assignment as shown.

[s1 s0]

FF labels

Sync Hunt

Sight

[10] [00]

[01]

r

r

r

e.

r

e.

r

e. r

e.

e

e

An output, s should be

true if in Sync state](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/debasicspdf-240215175513-2e86b8f3/85/Digital-Electronics-basics-book1_pdf-pdf-212-320.jpg)

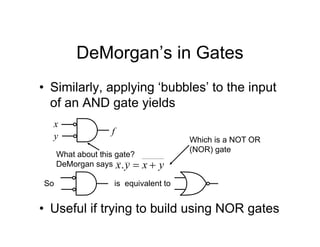

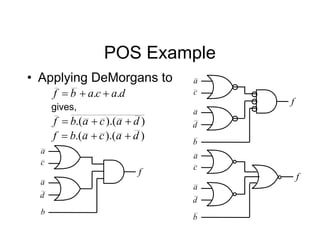

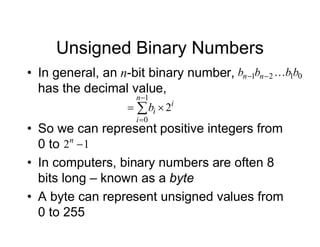

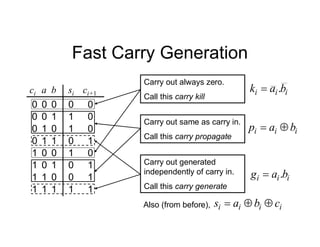

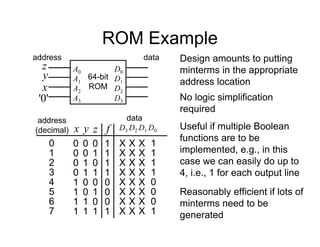

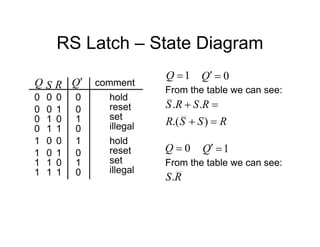

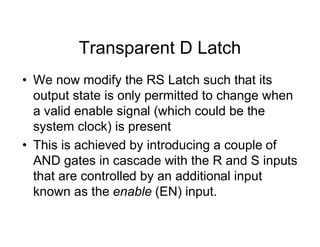

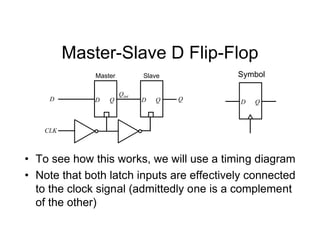

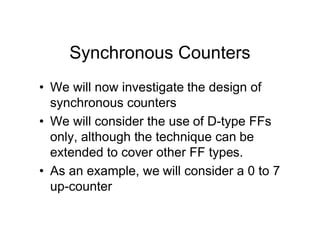

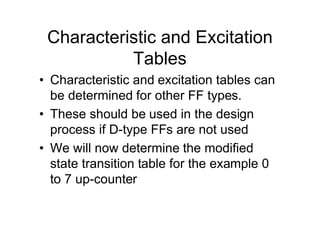

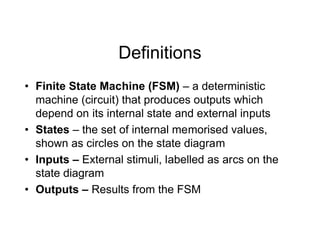

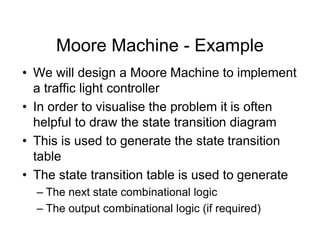

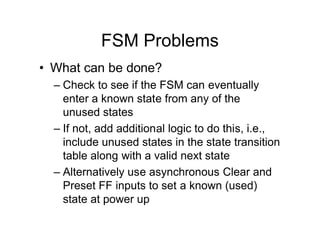

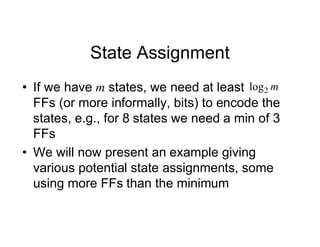

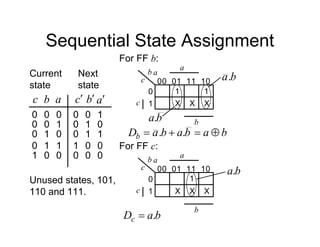

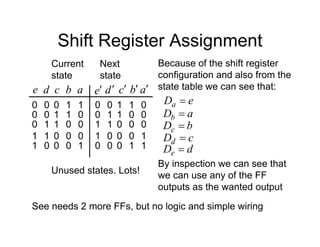

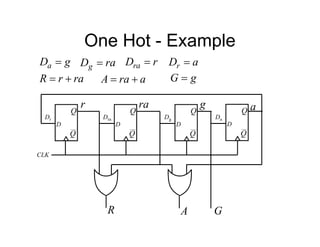

![Tripos Example

Sync Hunt

Sight

[10] [00]

[01]

r

r

r

e.

r

e.

r

e. r

e.

e

e

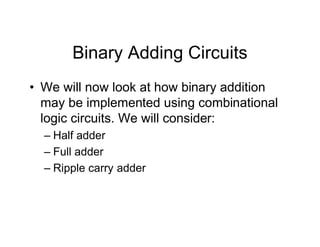

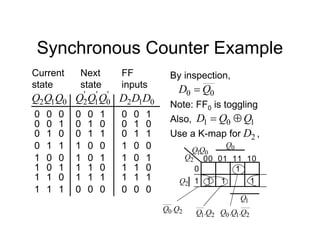

Unused state 11

Current

state

r

e

0

X

1

X

'

1

s '

0

s

0

1

0

0

Next

state

0

s

0

0

0

0

Input

1

s

X

0 1

0

0

1 0

0

1

0

1

0

1

1 0

1

1

0

0

1 0

0

0

1

X

0 0

1

0

1

1

1 0

1

0

1

X

X X

X

1

1

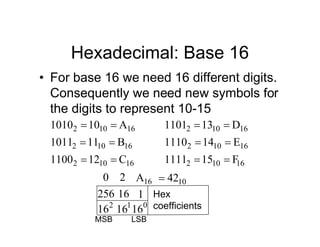

From inspection, 1

s

s ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/debasicspdf-240215175513-2e86b8f3/85/Digital-Electronics-basics-book1_pdf-pdf-213-320.jpg)

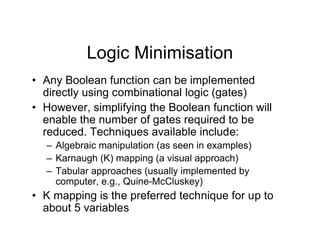

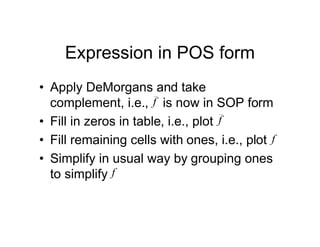

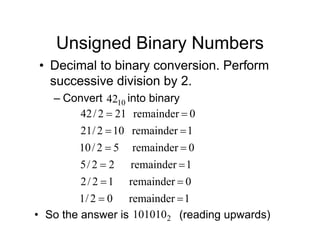

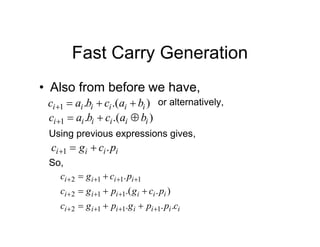

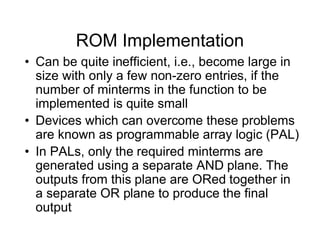

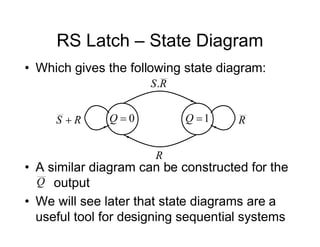

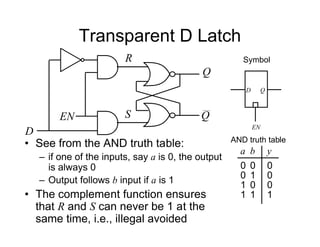

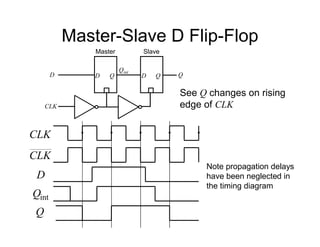

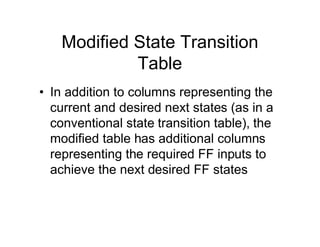

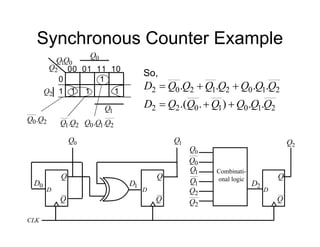

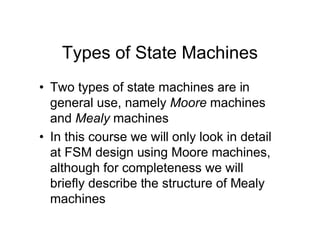

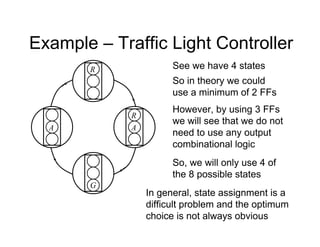

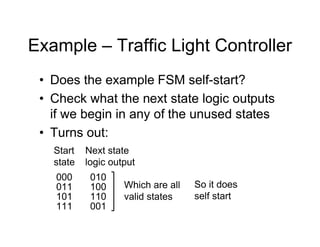

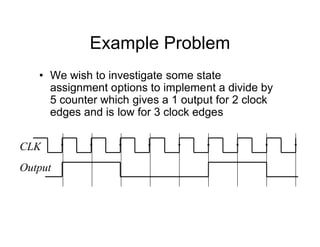

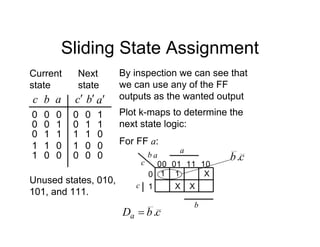

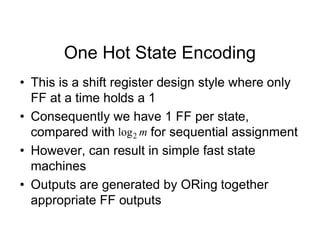

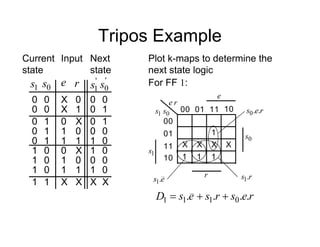

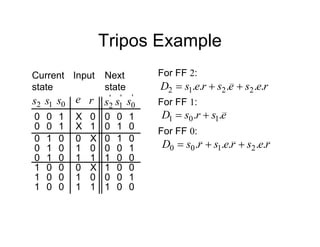

![Tripos Example

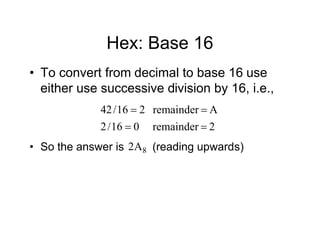

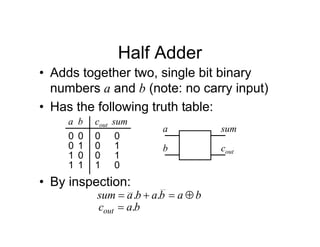

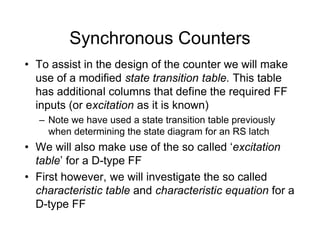

• We will now re-implement the synchroniser

using a 1 hot approach

• In this case we will need 3 FFs

Sync Hunt

Sight

[100] [001]

[010]

r

r

r

e.

r

e.

r

e. r

e.

e

e

[s2 s1 s0]

FF labels

An output, s should be

true if in Sync state

From inspection, 2

s

s ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/debasicspdf-240215175513-2e86b8f3/85/Digital-Electronics-basics-book1_pdf-pdf-216-320.jpg)

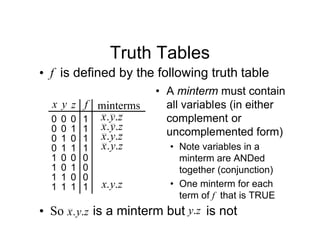

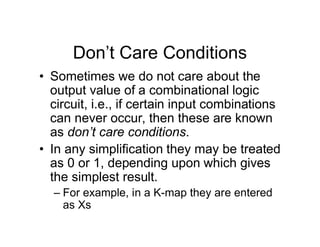

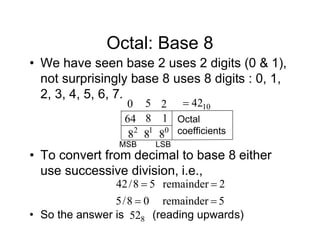

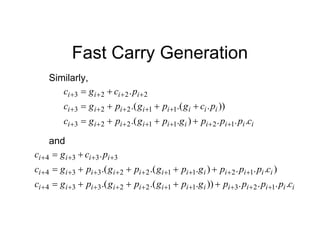

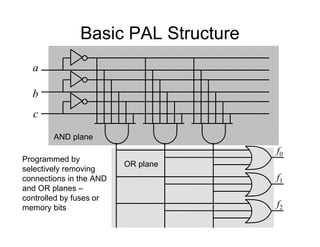

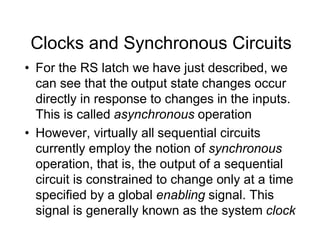

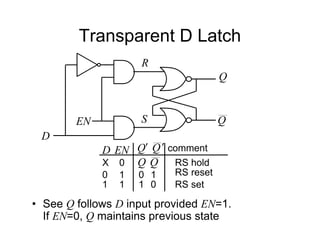

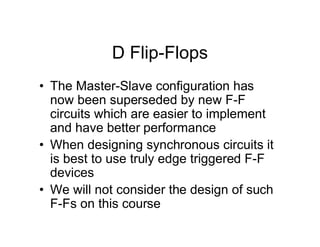

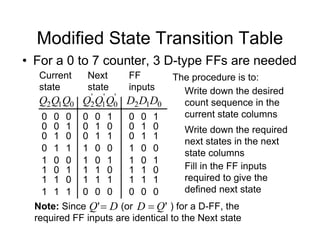

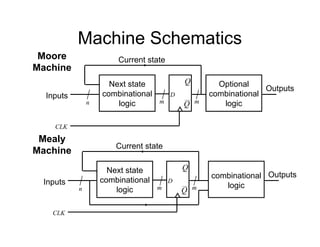

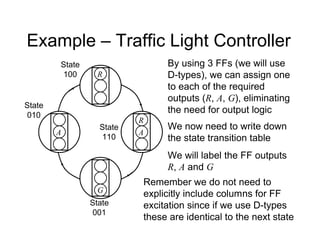

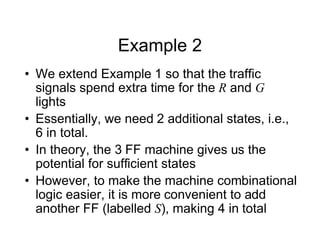

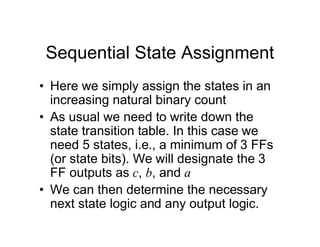

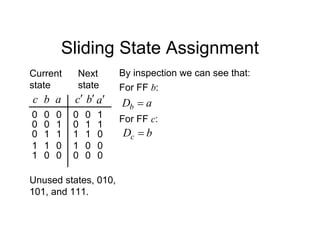

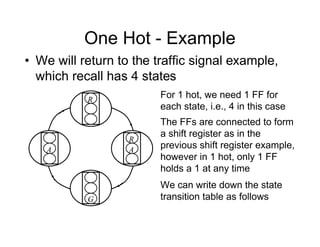

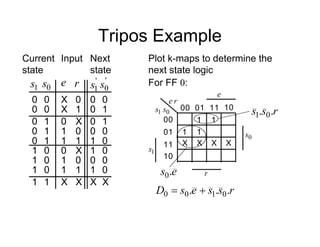

![Tripos Example

Sync Hunt

Sight

[100] [001]

[010]

r

r

r

e.

r

e.

r

e. r

e.

e

e

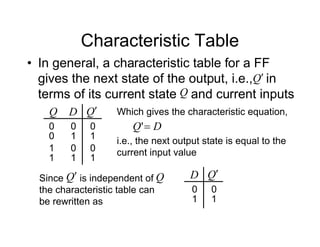

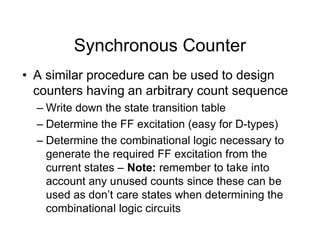

Current

state

r

e

0

X

1

X

'

2

s

0

0

Next

state

0

s

1

1

Input

X

0 0

0

1 0

0

0

1

1 1

0

0

1 0

0

X

0 1

0

1

1 1

0

'

1

s

0

1

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

s

1

1

1

0

0

0

'

0

s

1

0

0

1

0

1

0

0

0

0

2

s

0

0

0

1

1

1

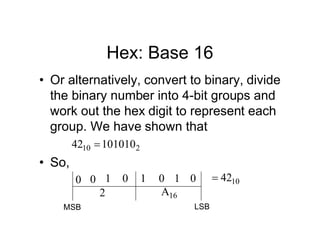

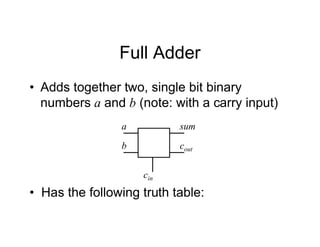

Remember when interpreting this table, because of the 1-

hot shift structure, only 1 FF is 1 at a time, consequently it

is straightforward to write down the next state equations](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/debasicspdf-240215175513-2e86b8f3/85/Digital-Electronics-basics-book1_pdf-pdf-217-320.jpg)

![Tripos Example

Sync Hunt

Sight

[100] [001]

[010]

r

r

r

e.

r

e.

r

e. r

e.

e

e

Note that it is not strictly

necessary to write down the

state table, since the next state

equations can be obtained from

the state diagram

It can be seen that for each

state variable, the required

equation is given by terms

representing the incoming arcs

on the graph

For example, for FF 2: r

e

s

e

s

r

e

s

D .

.

.

.

. 2

2

1

2

Also note some simplification is possible by noting that:

1

0

1

2

s

s

s (which is equivalent to e.g., )

0

1

2 s

s

s

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/debasicspdf-240215175513-2e86b8f3/85/Digital-Electronics-basics-book1_pdf-pdf-219-320.jpg)