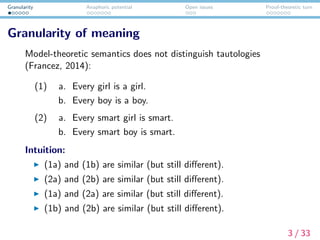

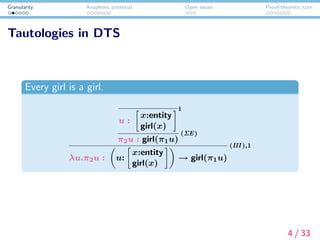

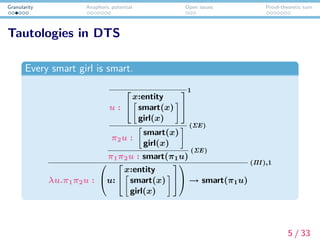

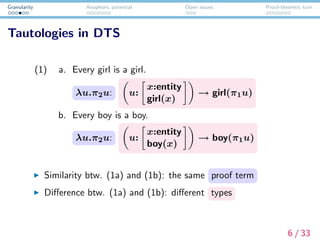

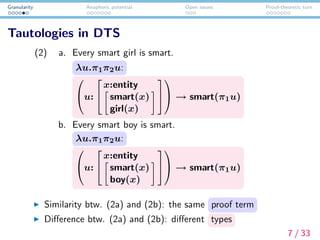

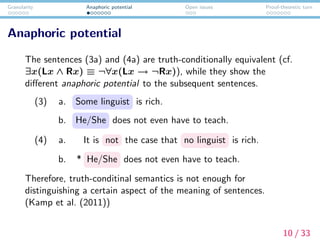

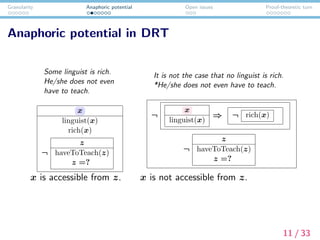

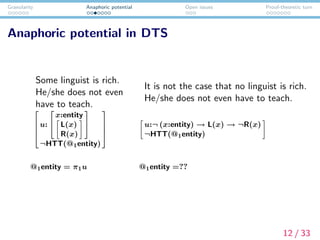

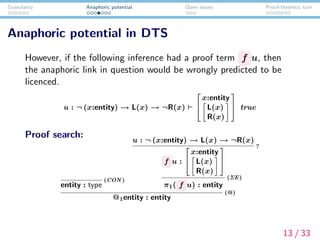

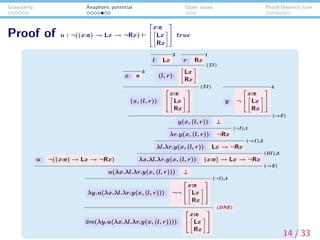

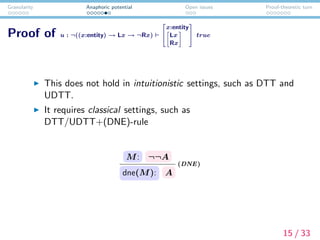

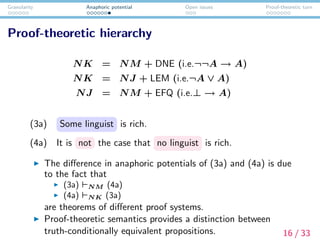

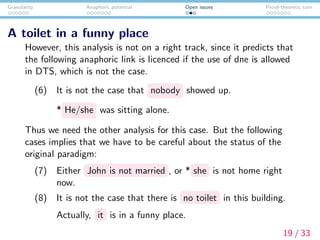

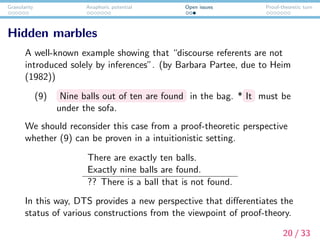

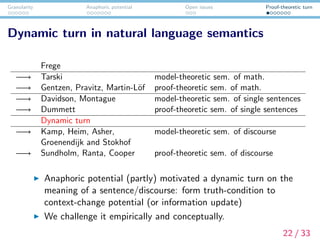

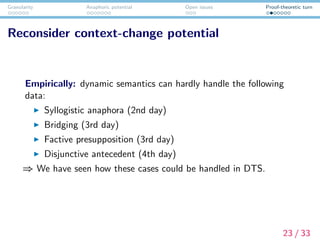

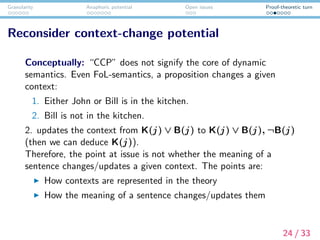

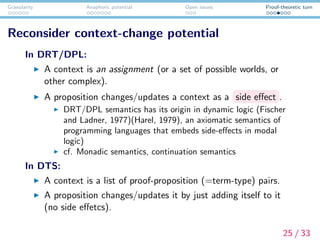

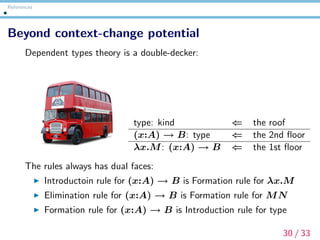

The document discusses the proof-theoretic approach to semantics, focusing on granularity, anaphoric potential, and open issues related to dependent type semantics. It contrasts model-theoretic and proof-theoretic semantics, highlighting how the latter can better capture nuances in natural language meaning through verification conditions. Additionally, it addresses the limitations of dynamic semantics and the empirical and computational motivations for adopting proof-theoretic methods in understanding anaphoric relationships.