This document provides an outline for a course on category theory from a logician's perspective. It introduces the instructor, Valeria de Paiva, and their background in category theory through their PhD thesis on Dialectica categories. The course will cover categories, functors, natural transformations, adjunctions, deductive systems as categories, and a taste of glue semantics. It emphasizes viewing proofs as first-class objects and using category theory for proof semantics rather than set-based models. The goal is to represent proofs explicitly rather than just knowing if a proof exists. The course will take an intuitionistic and constructive perspective on logic.

![Interested in Category Theory?

Dialectica categories are models of Linear Logic

Linear Logic (LL) introduced by Girard (1987): [...]linear logic comes from

a proof-theoretic analysis of usual logic.

LL the best of both worlds, the dualities of classical logic plus the

constructive content of proofs of intuitionistic logic.

Dialectica categories are a cool model of LL, still one of the best around...

Valeria de Paiva (NASSLLI2012) June, 2012 6 / 113](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nasslli2012-categories-120627074305-phpapp01/85/Category-Theory-for-All-NASSLLI-2012-6-320.jpg)

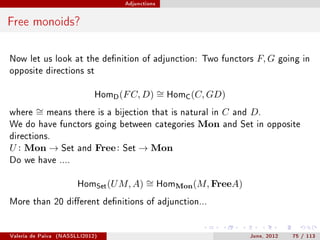

![Adjunctions

Free monoids?

Recall the functor Free : Set → Mon.

On an set A it produces the free monoid. i.e sequences of elements from

A, 'multiplied' by concatenation, (A∗ , [], concat).

On an set B it produces the free monoid (sequences of elements from B)

(B ∗ , [], concat).

Valeria de Paiva (NASSLLI2012) June, 2012 74 / 113](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nasslli2012-categories-120627074305-phpapp01/85/Category-Theory-for-All-NASSLLI-2012-98-320.jpg)

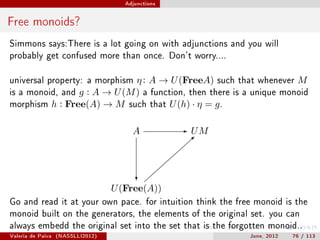

![Adjunctions

Free monoids?

Recall the functor Free : Set → Mon.

On an set A it produces the free monoid. i.e sequences of elements from

A, 'multiplied' by concatenation, (A∗ , [], concat).

On an set B it produces the free monoid (sequences of elements from B)

(B ∗ , [], concat).

remind me, what's the rest of the functor?

Valeria de Paiva (NASSLLI2012) June, 2012 74 / 113](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nasslli2012-categories-120627074305-phpapp01/85/Category-Theory-for-All-NASSLLI-2012-99-320.jpg)

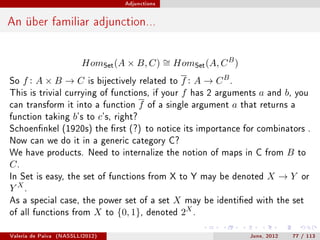

![Adjunctions

Free monoids?

Recall the functor Free : Set → Mon.

On an set A it produces the free monoid. i.e sequences of elements from

A, 'multiplied' by concatenation, (A∗ , [], concat).

On an set B it produces the free monoid (sequences of elements from B)

(B ∗ , [], concat).

remind me, what's the rest of the functor?

On a map f: A→B the action of Free, f ∗ is simply doing the function f

in each of the elements of A.

Recall also the `boring' forgetful functor U : Mon → Set. Given any

monoid (M, ·, e) it returns simply M . Given a monoid morphism

h : (M, ·, e) → (M , ·, e ), return simply the function h.

Valeria de Paiva (NASSLLI2012) June, 2012 74 / 113](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nasslli2012-categories-120627074305-phpapp01/85/Category-Theory-for-All-NASSLLI-2012-100-320.jpg)

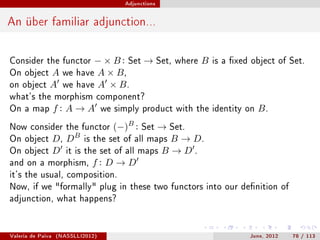

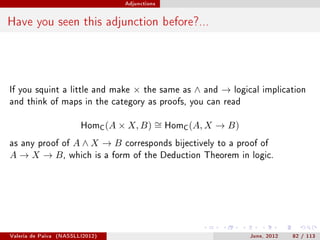

![Adjunctions

Cartesian Closed Categories...

A category C is called a cartesian closed category (CCC) if it has products

and if for each object X of C, the product functor −×X: C →C has a

X

right adjoint, written as (−) . That is we have

HomC (A × X, B) ∼ HomC (A, B X )

=

A minor modication, not insisting on real cartesian products, produces

the denition of symmetric monoidal closed category.

HomC (A ⊗ X, B) ∼ HomC (A, [X, B]C )

=

Valeria de Paiva (NASSLLI2012) June, 2012 81 / 113](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nasslli2012-categories-120627074305-phpapp01/85/Category-Theory-for-All-NASSLLI-2012-110-320.jpg)

![Deductive Systems as Categories

Recap..

So I goofed, should've dened:

An object C in a category D is an internal hom object or an exponential

object [A → B] or B A if it comes equipped with an arrow

ev : [A → B] × A → B , called the evaluation arrow, such that for any

other arrow f : C × A → B , there is a unique arrow λf : C → [A → B]

such that the composite

C × A →λf ×1A [A → B] × A →ev B

is f .

but yes, the bike metaphor is still valid...

Valeria de Paiva (NASSLLI2012) June, 2012 90 / 113](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nasslli2012-categories-120627074305-phpapp01/85/Category-Theory-for-All-NASSLLI-2012-121-320.jpg)

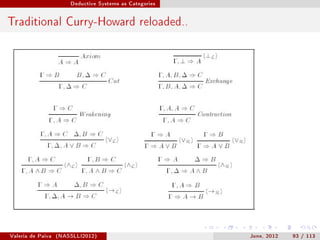

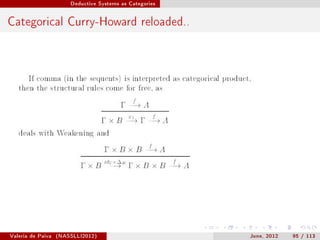

![Deductive Systems as Categories

Categorical Curry-Howard reloaded..

Soundness Theorem[Categorical Modelling of IPL]

Let C be a cartesian closed category with coproducts and let I be a model

of EqΣ in C. Then I satises any equation derivable from Eqσ using

equational logic.

Valeria de Paiva (NASSLLI2012) June, 2012 99 / 113](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nasslli2012-categories-120627074305-phpapp01/85/Category-Theory-for-All-NASSLLI-2012-130-320.jpg)

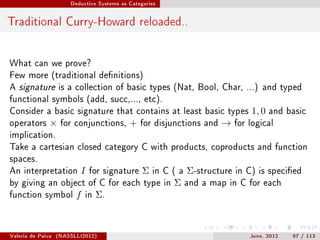

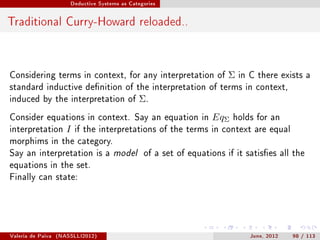

![Deductive Systems as Categories

Categorical Curry-Howard reloaded..

Soundness Theorem[Categorical Modelling of IPL]

Let C be a cartesian closed category with coproducts and let I be a model

of EqΣ in C. Then I satises any equation derivable from EqΣ using

equational logic.

Completeness Theorem[Categorical Modelling of IPL]

For all signatures Σ there exists a cartesian closed category with coproducts

C and an interpretation of the calculus in this category such that:

If Γ t:A and Γ s : A are derivable, then t and s are interpreted as the

same morphism only if t = s is provable from the equations above using

typed equational logic.

Valeria de Paiva (NASSLLI2012) June, 2012 100 / 113](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nasslli2012-categories-120627074305-phpapp01/85/Category-Theory-for-All-NASSLLI-2012-131-320.jpg)

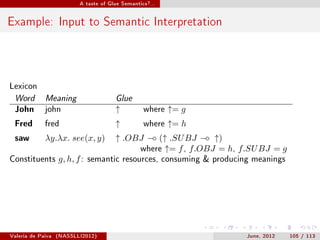

![A taste of Glue Semantics?...

Independence of Glue and Meaning

Original Glue (93) Curry-Howard Glue (97)

mixes meanings glue separates meanings glue

gjohn john : g

hf red f red : h

∀y. hy −◦ ∀x. (gx −◦ f see(x, y)) λyλx. see(x, y) : h −◦ (g −◦ f )

Some meaning separation rules:

• [[∀M. (rM −◦ ϕ)]]m = λM. [[ϕ]]m

• [[rM]]m = M

Some expressions can't be separated: gjohn −◦ f sleep(john)

Avoid these: derivations dependent on meanings,

and higher order unication needed to match meanings

Curry-Howard: good for understanding derivations

Original: good for understanding premises

Valeria de Paiva (NASSLLI2012) June, 2012 110 / 113](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nasslli2012-categories-120627074305-phpapp01/85/Category-Theory-for-All-NASSLLI-2012-141-320.jpg)