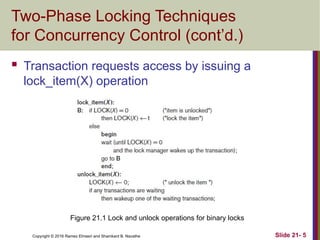

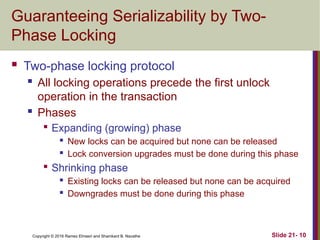

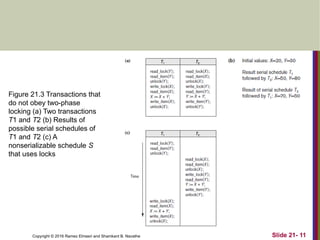

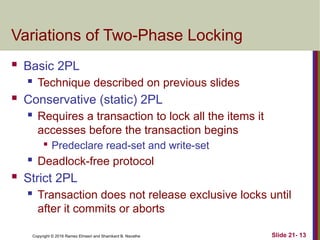

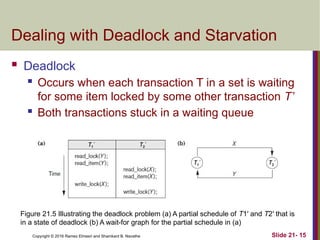

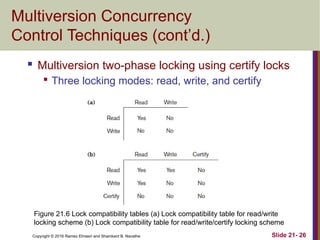

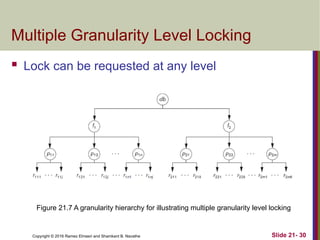

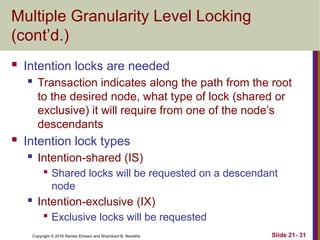

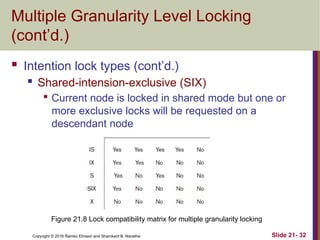

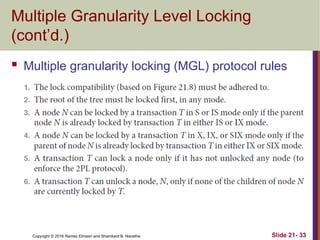

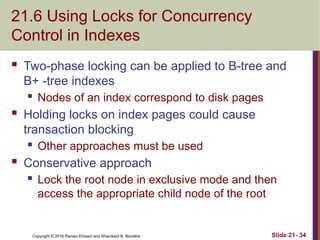

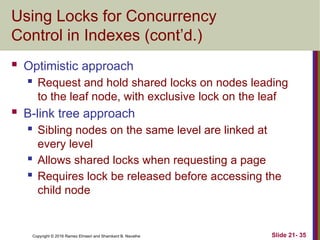

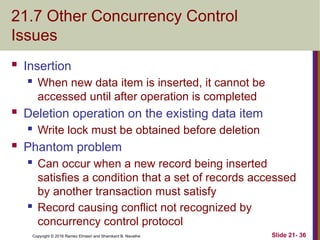

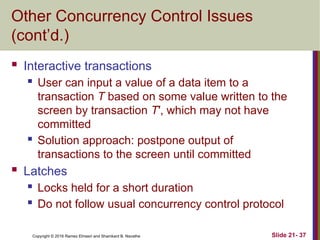

The document discusses concurrency control techniques in databases, including two-phase locking, timestamp ordering, and multiversion protocols. It explains how these methods ensure serializability and manage issues like deadlocks and starvation. The summary also highlights the importance of granularity in locking mechanisms and outlines specific approaches for managing locks in indexed structures.