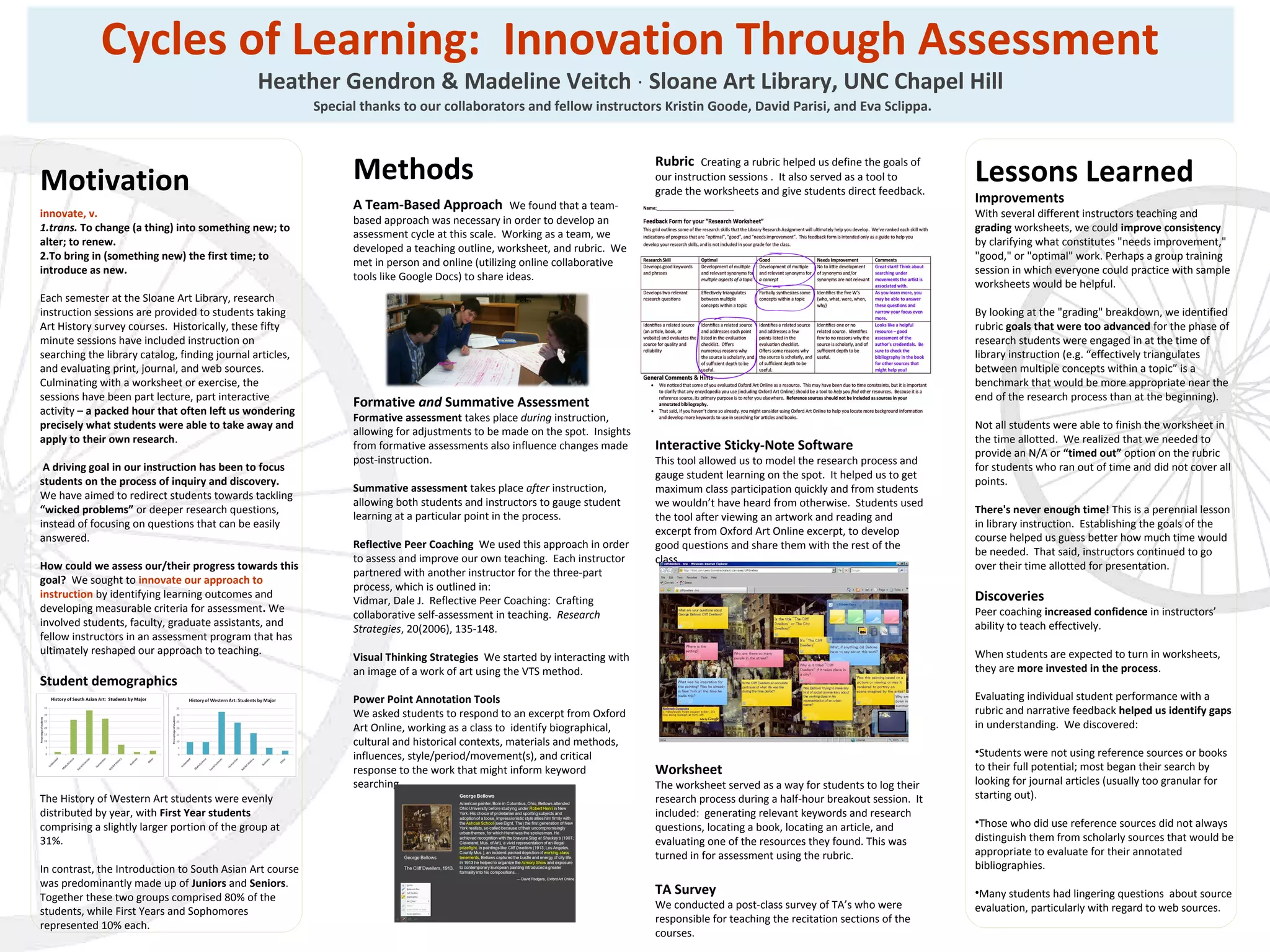

1) The authors developed an assessment program for library instruction sessions at the Sloane Art Library involving students, faculty, TAs, and fellow instructors to evaluate progress towards the goal of focusing students on deeper research questions.

2) A rubric and student worksheets were used to provide formative and summative assessments. Peer coaching was also used to assess instructor teaching.

3) Lessons learned included the need for more time, clearer rubric criteria, and guidance on using reference sources early in the research process rather than just articles. Student demographics and gaps in understanding were also identified.