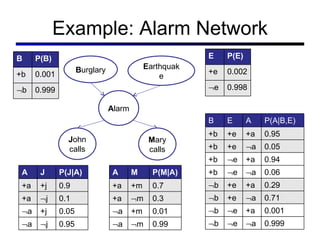

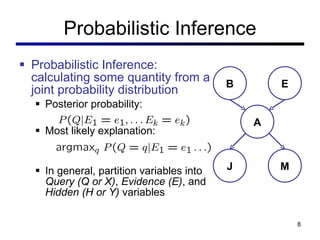

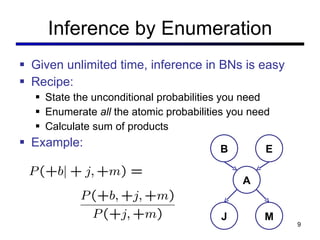

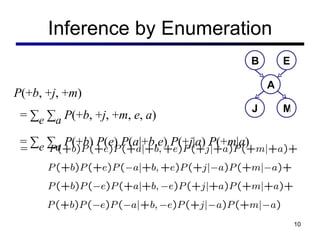

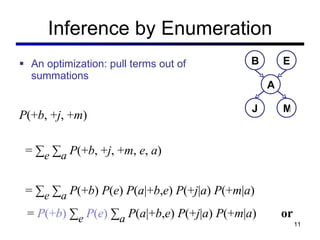

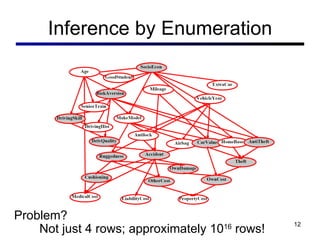

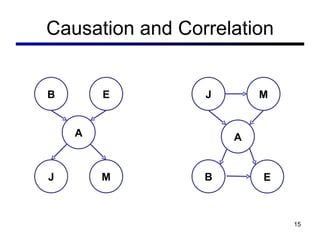

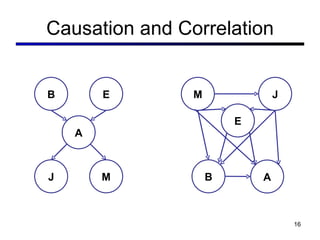

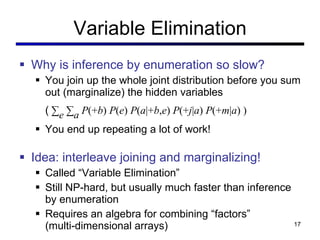

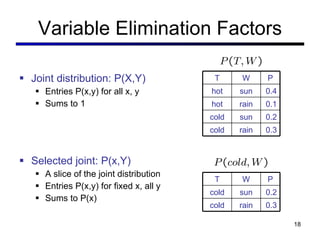

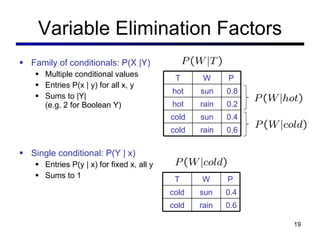

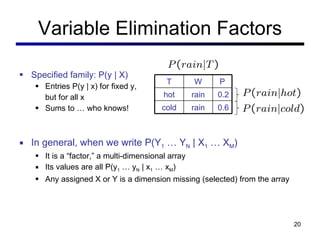

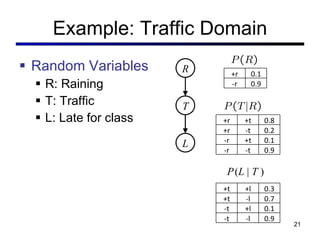

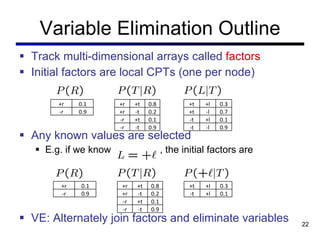

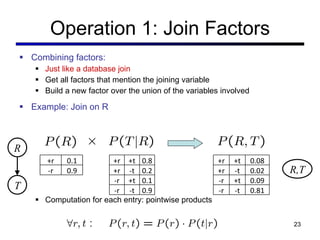

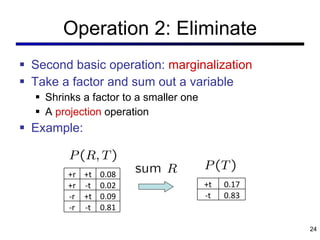

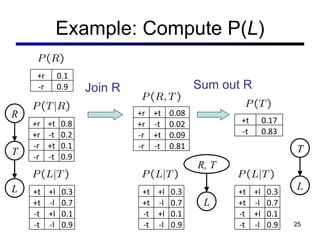

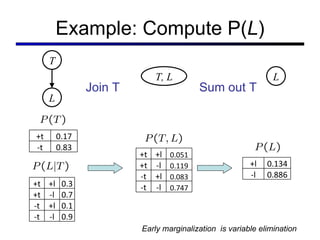

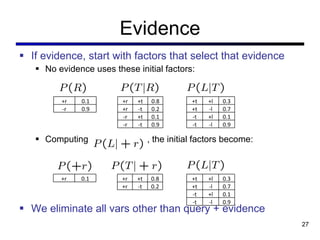

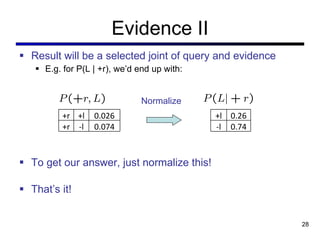

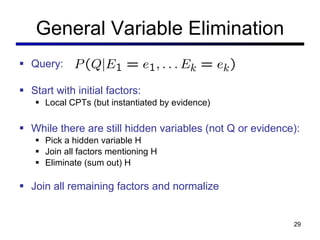

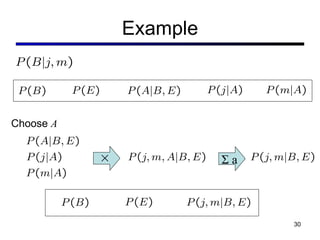

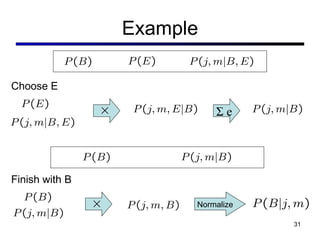

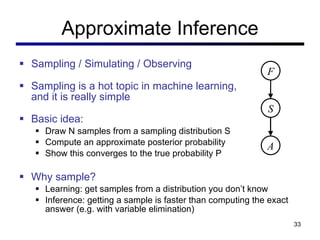

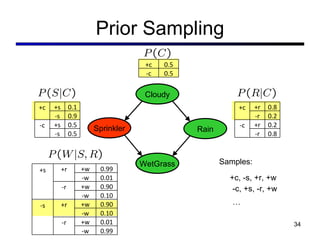

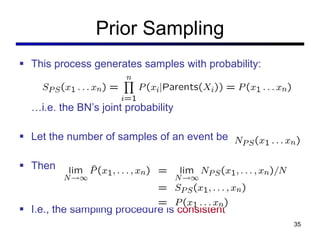

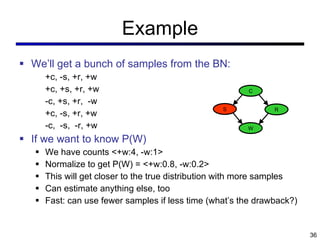

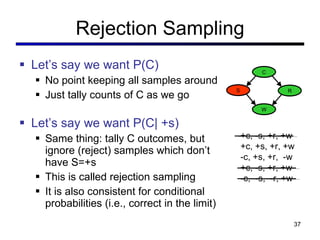

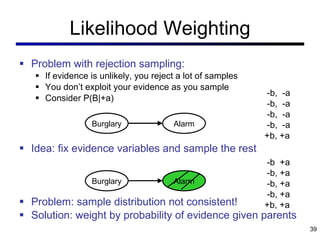

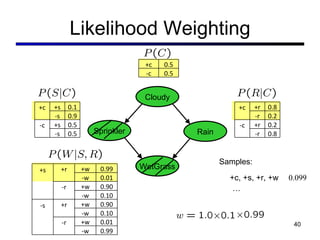

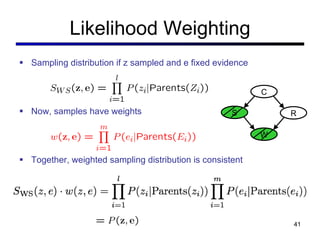

This document discusses probabilistic inference using Bayesian networks and variable elimination. It introduces the concepts of probabilistic inference, Bayesian networks, and variable elimination as a method for performing efficient inference. Variable elimination involves alternating between joining factors and eliminating variables to compute posterior probabilities without enumerating the entire joint distribution. Approximate inference methods like sampling are also discussed as alternatives to exact inference through variable elimination.

![Probabilistic Inference Joel Spolsky: A very senior developer who moved to Google told me that Google works and thinks at a higher level of abstraction... "Google uses Bayesian filtering the way [previous employer] uses the if statement," he said.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cs221-lecture4-fall11-111104223355-phpapp02/85/Cs221-lecture4-fall11-5-320.jpg)