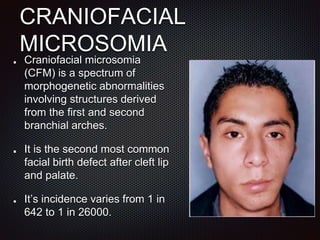

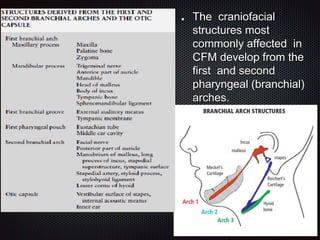

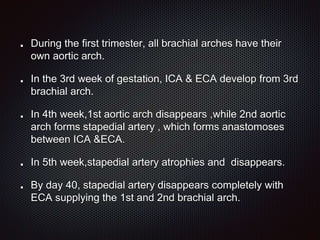

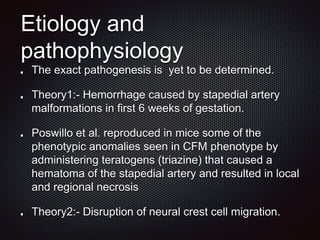

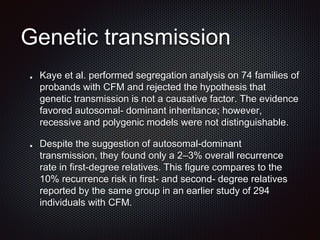

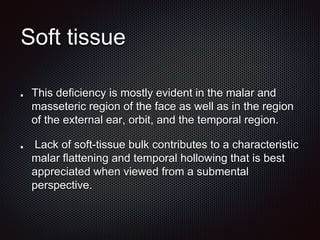

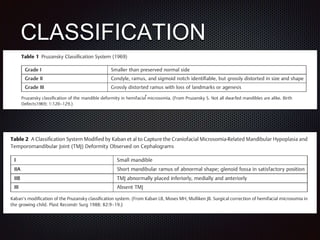

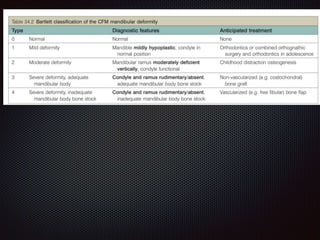

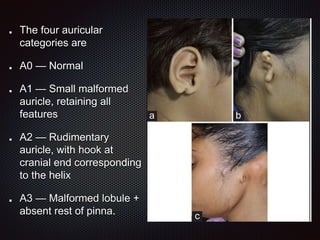

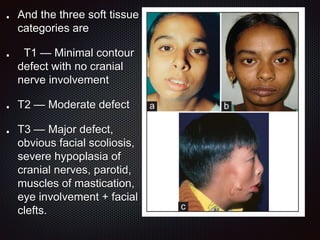

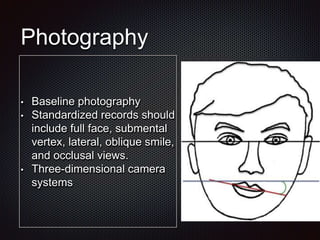

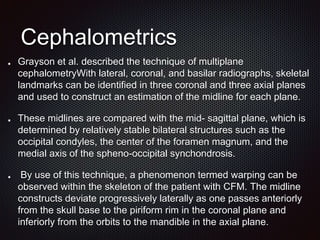

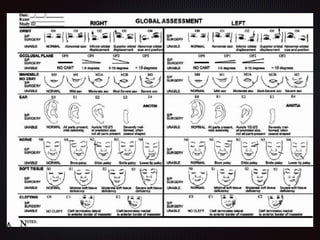

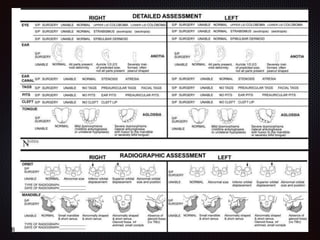

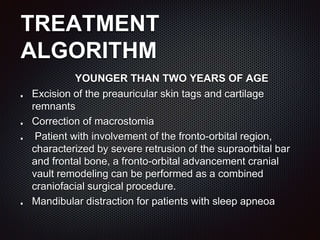

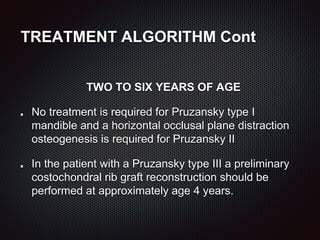

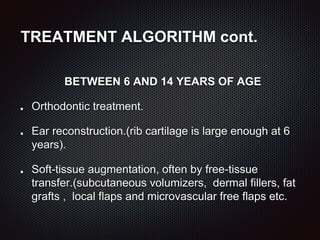

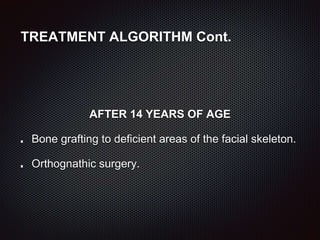

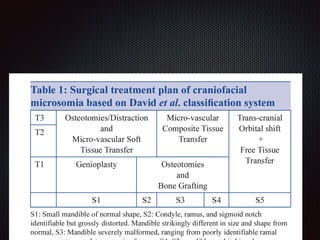

This document discusses craniofacial microsomia (CFM), a birth defect involving structures from the first and second branchial arches. CFM causes facial asymmetry and affects the mandible, ear, and soft tissues. It has various proposed causes but is thought to involve disruption of neural crest cell migration. Diagnosis involves assessing the skeletal, auricular and soft tissue involvement. Treatment planning relies on thorough documentation through photos, CT scans and cephalograms to characterize the abnormalities.