This document provides an overview of a conference presentation on narrative methods in health research related to the HIV epidemic in the UK and South Africa. The presentation discusses:

1) Why studying HIV is important given its psychosocial impacts and ongoing challenges with treatment and stigma.

2) Different types of social research that have been conducted on HIV including behavioral studies, stigma research, and narrative approaches.

3) Details of the presenter's narrative research studies interviewing people living with HIV in the UK and South Africa about medical, social and other support systems.

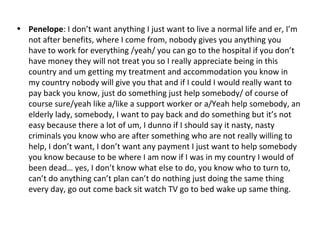

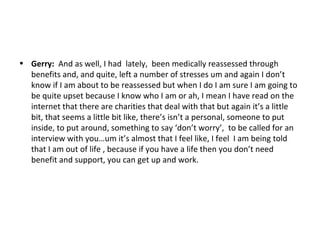

4) Key findings from the research including stories of normalizing HIV, resistance to changes in health systems, and difficulties accessing resources.