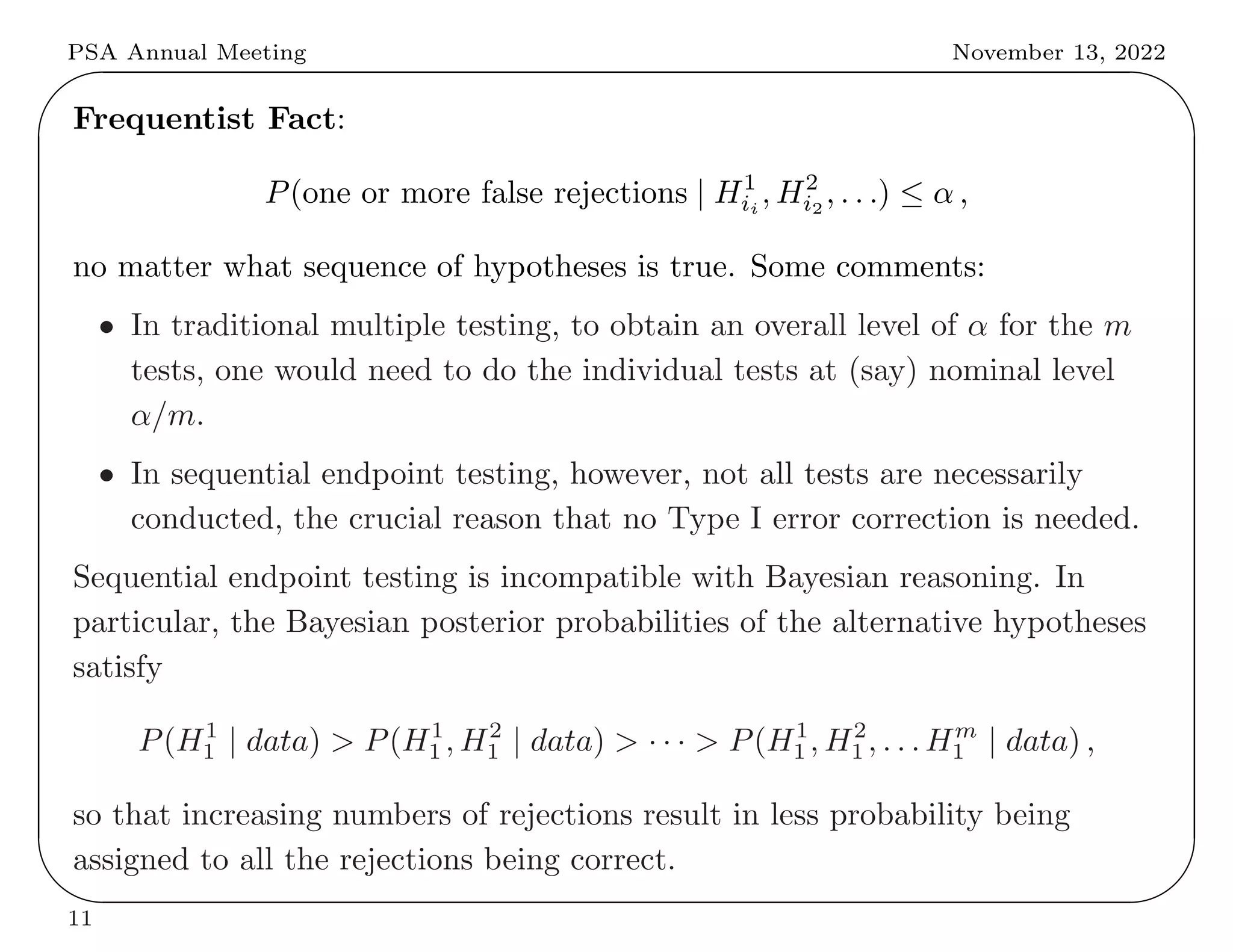

This document summarizes key differences between frequentist and Bayesian approaches to controlling for multiple testing. It provides four examples: (1) drug development screening where frequentists argue multiple testing could lead to false positives, (2) genome-wide association studies where both approaches use adjustments but derive them differently, (3) optional stopping where frequentists but not Bayesians adjust, and (4) sequential endpoint testing where the reverse is true. The document argues that while the approaches differ conceptually, they often arrive at similar practical solutions for controlling false discovery rates.