This document provides a summary of the book "Contemporary World Architecture" by Hugh Pearman. It discusses how the book comprehensively surveys international architecture at the turn of the new century, focusing on modern building types and the forces that shape them. It analyzes thirteen separate building categories and traces the pluralistic paths of architectural thinking from the 1970s to the start of the new millennium. The summary highlights how the book tells the evolving story of new forms and their underlying quest for aesthetic consensus during this time period.

![iiiiq|i]l

raSliiii111

ilil!!

Iiilllll](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/contemporaryworldarchitecture-151008001113-lva1-app6891/85/Contemporary-world-architecture-49-320.jpg)

![o

o

brickwork and decoration. Although Saudi Arabia

can produce a building such as the Palace of Justice

Mosque in Riyadh, 1992, by the Jordanian architect

Rasem Badran - a highly successful fusion of tradi-

tional Nadji architecture with modern techniques -

more normal are historicist mosques such as those

designed by the London-based architect Abdel Wahed

El-Wakil: most notably, his Al Qiblatain Mosque of

1987 in Medina. The divergent approaches of Badran

and El-Wakil have equal validity (the latter's has

more in common with Hindu temple builders), though

Badran is the more interesting to those who believe

that architecture is simultaneously capable of being

progressive and traditional. Badran's mosque, though

rich in ornament to mmimalistically inclined eyes, in

fact starts gently to abstract the elements of its tradi-

tion, which is entirely in keeping with a desert archi-

tecture. One might cite the precedent of Arthur

Shoosmith's Garrison Church in New Delhi, 1928-30,

which abstracts the image of the square-towered

Anglican church in brick rather as Edwin Lutyens pro-

duced the eternal form of the Cenotaph, the empty

tomb. Again, one can point to the return of traditional

forms. The British may not exactly have ushered in an

age of radical architecture during their stewardship of

India, but the promise of Shoosmith's Garrison Church

seemed to have faded by the time AGK Menon came

to design St Mary's Cathedral in Varanasi, 1990-3 -

:;

'

—tar —1]7 I

i I

mt uv /](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/contemporaryworldarchitecture-151008001113-lva1-app6891/85/Contemporary-world-architecture-161-320.jpg)

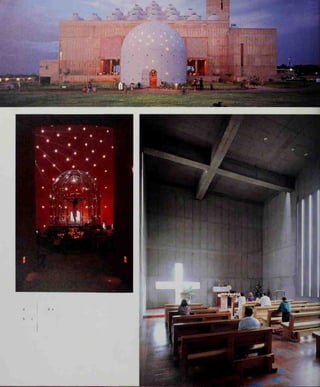

![while the tall prow of the church (the bows of the

ark, If you like) faces away from the village towards

the higher ground that was the source of the

avalanche. Inside, two arches of Cyclopean scale

form the spine of the building while the walls, mas-

sively thick at ground level, gradually taper towards

the top, giving the interior a funnel shape. At their

thickest point behind the altar, a Romanesque apse

IS virtually quarried out, its banded stonework recall-

ing the rural chapels of the Normans. 'The attempt,'

remarked Botta, 'more symbolic than actual, [was] to

handle huge forces.' Sheltered within this dam-like

stone shell, one looks up past the arches and sees

the sky. The interior plan is rendered more subtle by

the fact that the rectangular nave plan of the lost

church is carved out of the thickness of the oval plan

of the new one. Angled, deeply incised, doors lead

defensively from a walled courtyard into the church

either side of the arch-spine. The building, like the

windowless fortress-churches of frontier districts,

appears more secure than it is, for it is still a puny

relative to the forces that could be ranged against it.

But its task is to represent sanctuary and security.

Having designed the Mogno church in

response to a natural calamity, Botta then with

seeming casualness took what amounted to a mould

of the tapering interior of Mogno, inverted it, and

expressed it externally as the cone-shaped roof of

the Church of Beato Odorico, Pordenone, 1987-92;

placed a cylinder within a cube for a church at

Sartirana, 1987-95, and finally re-applied the

Mogno form, on a large scale, at Evry Cathedral,

1988-95. No-one could accuse Botta, as they might

Jean Nouvel, of being profligate with his shape-

making and materials. Evry is so similar to Mogno,

that It appears to deny it its allegedly site-specific

reason for being. It is circular in plan, with a more

complex variant of Mogno's glazed roof on the angle.

The great thickness of the walls here used for ancil-

lary rooms and stairs, with a related apsidal arrange-

ment behind the altar, has a funnelling effect on the

interior, and is plugged into an enclosing courtyard.

But for Botta, the surroundings at Evry are no less

potentially hostile than those at Mogno. The differ-

ence is that, while Mogno shelters the community

symbolically against the forces of nature, Evry does

exactly the same against the forces of modern archi-

tecture. For Botta, Evry's New Town represents the

o

o

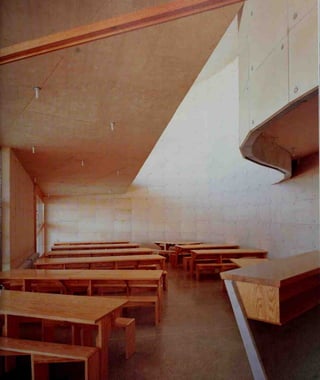

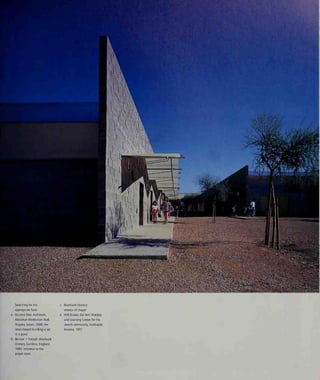

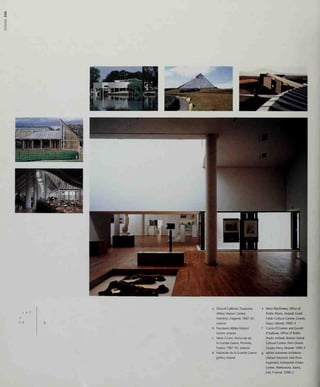

Botta's architecture is ready-

made for churches. The ark,

the sanctuary, the tomb:

Mario Botta, Church, Mogno,

Switzerland, 1986-96: the

elliptical drum is sliced by the

disk forming the roof

Mario Botta, Church, Sartirana,

Switzerland, 1987-95: altar

Mogno Church: the striations

of light from the skylight

crossing the masonry bands

evoke strong compansons

with Evry Cathedral

Sartirana Church: the cylinder

withm the cube

Mario Botta, Church of Beato

Odorico, Pordenone, Italy,

1987-92: looking up towards

the top of the cone

Church of Beato Odorico: view

from beyond the altar

Church of Beato Odorico: the

'beehive' cone of the church](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/contemporaryworldarchitecture-151008001113-lva1-app6891/85/Contemporary-world-architecture-167-320.jpg)

![o

u

very worst kind of modernist planning - rigidly func-

tional, with no room, as he says, for anything but

working and sleeping. 'The objective,' he declared,

'was to offer the city a call to believers that could,

even more importantly, [my italics] have strong mean-

ing for non-believers ... For them, the cathedral can

be seen as a moment of silence and meditation, not

necessarily religious or as a response to the need for

certain functions, but as a place where any citizen

may pause for a while.' In short, Botta wanted to

recapture the perceived community role of the

medieval cathedral, with the modernist housing

estates around standing in for the hovels of the peas-

ants of the Dark Ages. Nevertheless, there are some

highly original touches, although most had previous-

ly occurred on his secular buildings: Botta designed

Evry with a circlet of trees running round the perime-

ter on top, with a covered walkway beneath the tree-

line. While the glazed roof aspires to heaven, the

building thus has a more prosaic function as a van-

tage point. In a way, Botta has evolved his own myth

of church-making that, while clearly personal, he

applies with exactly as much flexibility or rigidity as

those designing mosques. For them, it is the symbol-

ism of the Prophet's House: for him, it is the shelter-

ing cave and the hillside above. And if proof were

needed of the old dictum that museums are the

cathedrals of today - why, Botta took the form of

Mogno and Evry and made it the centrepiece of his

Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco, 1989-95,

(see 'Visual Arts') and for identical reasons: to assert

its presence in the city, to constitute a point of

reference, to bring light washing down from above,

to set up a dialogue with the community, and to act

as an ark of tradition against the glassy vacuousness

of the business district round about. There is even an

apsidal detail at the root of the great circular atrium

beneath that slanting eye-on-the-sky (which at one

point Botta wanted to crown with trees). Wasting

not a single idea, Botta then took the idea of the

walkway round the roof, as used at Evry, and applied

it right back down the scale for his little chapel at

Monte Tamaro in the Ticino. This time he used the

Mogno giant arch element externally, as a bridge

leading to the apex of the roof. Like any medieval

church builder, Botta has his specialized vocabulary:

it is simply that it is personal to him, rather than to

any generalized tradition or system of belief.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/contemporaryworldarchitecture-151008001113-lva1-app6891/85/Contemporary-world-architecture-168-320.jpg)

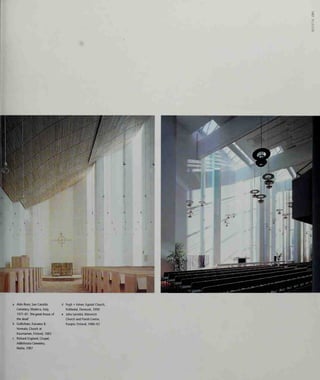

![s

o

'The merchant has always been and will always be

most successful where his activity is integrated with

the widest possible palette of human experiences

and urban expressions.'

Victor Cruen, 1973.

There are shops, and there is retail. A 'shop' -

a term which includes bars and restaurants - can be

the most designed object on earth, subject to the

attentions of the best and most fashionable archi-

tects, and has a glorious, brief, life. One thinks of

Los Angeles watering holes such as the 1986 Kate

Mantilini Restaurant in Beverly Hills by Morphosis, or

RoTo's Nicola Restaurant of 1992-5, or of Branson

Coates' series of Tokyo bars in the 1980s, or of any

hotel restaurant by the designer Philippe Starck.

Retail, in contrast, is a huge and multi-headed organ-

ism. Retail means zoning. Retail means high-streets,

malls, edge-of-town superstores, great big metal

sheds, enormous car parks. Retail has a relatively

long, and usually inglorious, life. One thinks of the

West Edmonton Mall in Canada, or the Mall of

America in Minnesota, both involving Maurice

Sunderland architects - themed private kingdoms.

The world of big retail is a world where architects

with famous names seldom venture. Small wonder: it

is a highly specialized discipline which, like hospital

design, a relatively few practitioners guard jealously

working closely with an equally tightly drawn

circle of financiers and developers. Retail develop-

ments scarcely ever show up in architectural

awards schemes, nor, usually, do their originators

want them to.

A perusal of the standard art-historical

accounts of twentieth-century architecture reveal

that retail gets short shrift if it is mentioned at all.

It is as if it does not exist, yet by any standards the

shopping mall, to take one manifestation of the

genre, has since the Second World War had a greater

impact than almost any other building form, both on

the way people conduct their lives and on the

appearance and usage patterns of towns and cities.

For example: if a modern mall is carved out of a town

with an inherited medieval street pattern, then the

maximum force for physical change is dictated not

so much by swarms of people and their cars, nor

even by the very large areas needed for the big

stores, important though these are - but by the

turning circle of the maximum permitted length of

delivery truck, which is enormous. Towns have to be

broken up to accommodate this dimensional need.

Why the curious silence about retail develop-

ments, save for those rare nineteenth-century exam-

ples that fall within the art-historical ambit because

of their use of advanced materials - the Calleria in

Milan, say, or the great Parisian department stores of

the belle epoque? Robert Venturi has noted the

'mental-aesthetic blackout and photographic crop-

ping' used by architectural historians to focus in on

the things they want to see, to the exclusion of the

rest of the built environment. Venturi notes the way

Japanese temples and shrines are described as dis-

crete objects when they are sited - especially in the

case of Kyoto - in teeming and highly commercial

urban surroundings. This, of course, exemplifies

Venturi's 'complexity and contradiction' theory. In

general American architects and some critics are

more comfortable with commercialism than their

European counterparts - and Venturi's and Denise

Scott Brown's 1972 homage to the Las Vegas com-

mercial strip. Learning from Las Vegas, is rightly cele-

brated. But when Venturi and Scott Brown returned

to the Strip in 1994, they found that it had changed.

The original Strip, rising from the desert, had been

urban sprawl 'at its most pure'. By the mid-1990s, the

Strip had been built up and renamed Las Vegas

Boulevard. '[It] has become in some ways the equiva-

lent of the shopping mall that accommodates the

pedestrian in safe and explicitly artificial environ-

ments,' Venturi noted. He was making no overt value

judgements - his commentary suggests that he saw

this as merely part of the evolution of cities over time

in all kinds of ways. Vegas had changed from pop

culture to gentrification, from pop taste to 'good'

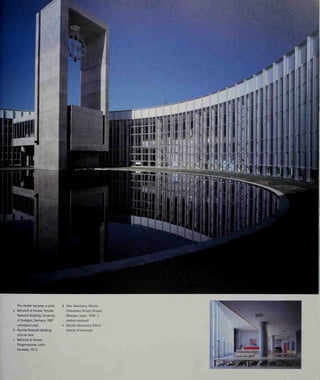

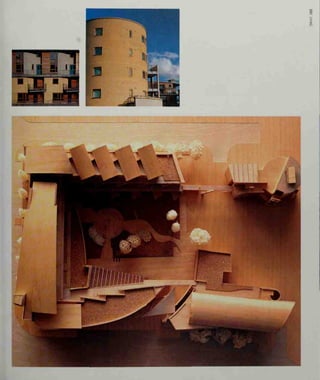

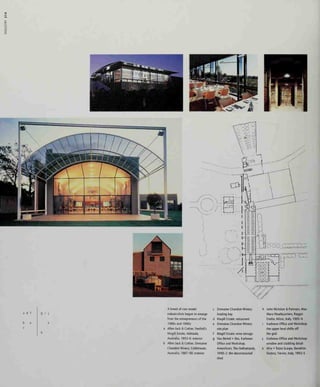

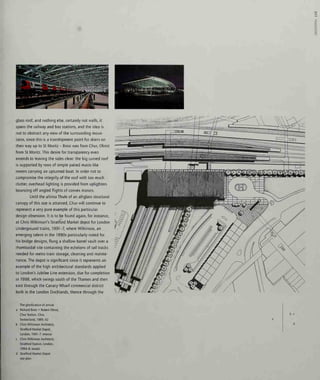

Impermanence offers the

radical an outlet:

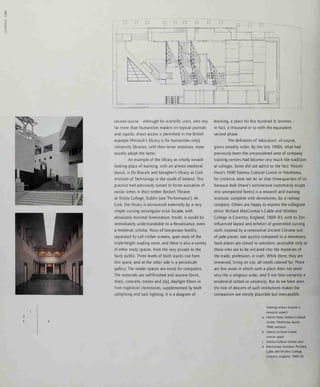

a Branson Coates, Caffe Bongo,

Tokyo, 1986

b Branson Coates, Bohemia

Jazz Club, Tokyo, 1986

c RoTo Architects,

Nicola Restaurant,

Los Angeles, 1992-5

d Nicola Restaurant:

interior view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/contemporaryworldarchitecture-151008001113-lva1-app6891/85/Contemporary-world-architecture-178-320.jpg)

![o

c

=...=:] *^

>

n n an n n

1

rr

":"•"•

t"~™"3

^:^

„

—

=^](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/contemporaryworldarchitecture-151008001113-lva1-app6891/85/Contemporary-world-architecture-323-320.jpg)

![moved on by the time it came to the 1 50-bed

Kandalama Hotel at Dambuila, 1991-5. Built deep

in the dry-zone jungle of the interior, it is positively

Miesian in the rigour of its timber-framed detailing,

the horizontals extending into timber-slatted balconies

and green planted roofs and terraces. However, it is

not a rectilinear plan but a ribbon. Its narrow wings

are cranked along a contour against a rock face, over-

looking an extensive reservoir. It manages to be at

one with its setting, probably precisely because of its

ultra-simple post-and-beam construction, raised on

pilotis above the otherwise undisturbed landscape.

The Kandalama is an example of an 'eco-hotel',

designed for minimum environmental impact, draw-

ing water from its own wells and with its own

sewage-treatment plant: a model for other regions.

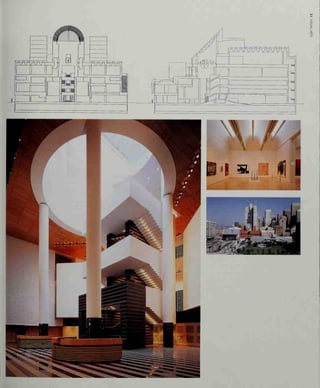

Nouvel, the sophisticated Westerner, is not

such a curious name to yoke with that of Bawa.

Nouvel's Hotel Les Thermes, 1990-2, in the spa town

of Dax, southwest France, has an external facade of

full-height timber shutters, a related solar canopy at

eaves level, and big awnings all round the double-

height common areas at the base - details drawn

from, but not directly copying, the hot-climate indige-

nous architecture. Similarly his earlier Hotel

St James in Bordeaux, 1987-9, broken down into a

cluster of smaller forms rather than being a single

imposing structure as in Dax, sports an external gril-

lage of oxidized steel. Instead of the folding external

shutters of Dax, the grilles rise on gas struts where

they cover the windows. The appearance of the com-

plex makes clear reference to the tobacco-drying

sheds of the region. Inside, the rooms were finished

in plain waxed plaster and concrete - an early exam-

ple of the luxury monk's cell look that was to become

one of the architectural cliches of the 1990s as 'mini-

malism' came back into fashion and architects led by

John Pawson indulged in interiors of 'exquisite

restraint' for exquisitely wealthy clients.

By 1997, even London's boutique hotelier

Anouska Hempel had abandoned her other oriental

cluttered chic look in order to create her eponymous

minimalist-with-a-twist hotel. The Hempel. A noted

stickler for detail, Hempel was quoted as saying,

when her hotel was finished but not yet open:

'Terrible things go wrong when you're working in the

minimalism [sic] because there's nothing for the eye

to look at except light and shade, so it sees all the

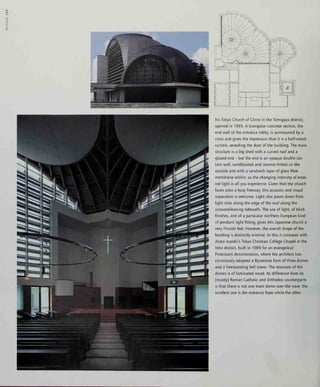

The 'boutique hotel' is now an

established type:

a Jean Nouvel, Hotel Les

Thermes, Dax, France, 1990-2:

exterior view

b Jean Nouvel, Hotel St James,

Bouiliac Bordeaux, France,

1987-9

c Hotel Les Thermes:

swimming pool

d Anouska Hempel Designs,

The Hempel, London, 1997

Kisho Kurokawa, Hotel

Kyocera, Kagoshima, Japan,

1991-5: the legacy of John

Portman's atrium hotels

Philippe Starck, Penninsula

Hotel, Hong Kong, 1987

Aldo Rossi, Hotel II Palazzo,

Fukuoka, Japan, 1987-9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/contemporaryworldarchitecture-151008001113-lva1-app6891/85/Contemporary-world-architecture-334-320.jpg)

![^^-.^r^

if

*j '4 f# fi • t ' t 'i i

•B IL

i Ml

aHH

who refused to design to any theme but his own -

paradoxically found himself both involved and rea-

sonably happy with the process. Significantly Cehry's

long-term artist collaborator, Claes Oldenburg,

refused to work with him for Disney. Cehry's conclu-

sion was that both Oldenburg and Venturi had the

same problem: Those two get very close to the

Mouse,' he said, 'but Oldenburg and Venturi are also

commentators.' It was that implied commentary that

the Disney organization could not take, and it was

the lack of it in Cehry's case that they appreciated.

Venturi and Scott Brown agreed with Cehry's

analysis of the situation when I put the transcript

to them. 'Denise Scott Brown and I think Frank

Cehry's reporting and interpretations are sound,'

Venturi wrote, adding in parentheses: 'I remember

also at a later meeting with the Disney Imagineers

in California, Steven Izenour [another partner] and I

were called vulgar ...'

One pauses to consider the delicious irony of

the Disney organization convincing itself that one of

America's most academically inclined architects was

a vulgarian. It is a mark of just how seriously Walt's

empire takes itself that it could not recognize a

parallel seriousness m the work of Venturi. He is

clear on the credentials of his practice, concluding:

'There is the irony that Denise Scott Brown was the

first "respectable" architect - along with Charles

Moore - to acknowledge Disneyland, taking her

UCLA students there in the mid-60s. And we both

are fundamentally in our work as a whole (rather

than just for Disney) employers of iconography,

symbolism as valid (and historically substantiated)

elements of architecture.'

Interestingly it is Cehry's view that the forbid-

den ironic view of Mickey as proposed by Venturi,

would have worked in France in a way that it could

not in the United States, presumably on the grounds

that the French, with their European self-awareness

and un-American cynicism, would have noticed and

appreciated the wry gesture.

Such national stereotyping works both ways.

As Jean Baudrillard once acidly observed, Disneyland

exists in order for Americans to believe that what lies

outside it is real. What this stinging generalization

overlooks is that the likes of Venturi and Cehry, with

their Europhile scholarliness, are also 'Americans', no

less than the perhaps more naive Robert Stern, of

whom more in a moment, and Craves. However, the

fact that Crumbach was the only European architect

to get to build at EuroDisney - out of an initial trawl

that also included Bernard Tschumi, Hans Hollein,

Rem Koolhaas, Jean Nouvel, Jean-Paul Vigier and

Aldo Rossi - tells its own story. Rossi got a certain

way down the line but then resigned under pressure.

He wrote to Eisner, astutely (especially given Craves'

built references to the same sculptor-architect in

Florida) comparing his problems with those of Cian

Lorenzo Bernini. Bernini had fallen foul of an over-

demanding and petulant Sun King, Louis XIV, when

asked to produce designs for the Louvre. Rossi told

Eisner: 'I realize I am not Bernini, but you are not the

king of France. I quit.'

Venturi makes no reference to his Parisian

disappointment in his published writings, although

there is a tantalizing essay, written in bursts from

1993 to 1995, comparing the Americanization of

Pans with what he saw as the 'Parisification' of

Philadelphia, his home city. In it he remarks, 'What

if I were to say there's nothing wrong with the

Champs-Elysees that a few billboards won't cure?

Is that so different from saying how about 'grands

projets for South Broad Street?' Despite the

EuroDisney setback, the Mouse did not entirely

forget Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown;

the projects they got to do - 'in the interstices'

as Venturi puts it - include a minor office building

on the Burbank campus and a fire station, the

ponderously named Reedy Creek Emergency Services

Center at Lake Buena Vista, part of Walt Disney

World in Florida.

At Lake Buena Vista, Venturi Scott Brown

and Associates produced a building that looks as if

it is a child's building-brick composition - a true

b c

d

e

Venturi Scott Brown and

Associates, Reedy Creek

Emergency Services Center,

Orlando, Florida, 1992-4

Aldo Rossi, Celebration Place,

Orlando, Florida, 1991-6:

Rossi's office buildings at the

heart of Celebration

Celebration Place: serious

urban planning for Disney

Robert A IVl Stern, Wlasterplan,

Celebration, Florida, 1991

Philip Johnson, Town Hall,

Celebration, Florida, 1994-6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/contemporaryworldarchitecture-151008001113-lva1-app6891/85/Contemporary-world-architecture-340-320.jpg)

![^..

,;-i>:>:'rj5^f/|/2tj

TTwiras

**ii''5

3^Ii

'^i^'O-'^i^l^-i^'i:'!

,

i-S'i5^'i'^5'»*-i^*2'

» >>

i' A- A' i. ^ A' A.

:i§';§)d^^4! lit' :]&:'&'

>»^

qjfi^%%^^ # « ^ » ft « :f {£ « « » Ji'

^^i^^^qj^^^^^^'<|^ ^||: ^' ^i t§: i^ ig:

^'% tg;

^K^ n^^ri^!^''W^l<-'i'i-v'i"r-i'l''l--i-'X](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/contemporaryworldarchitecture-151008001113-lva1-app6891/85/Contemporary-world-architecture-398-320.jpg)

![00

]

5.

^^^."ll

W^ '«inin>»Atij|^^^pUf HtJ: :: J ^^ - _sr«=^H^^5, ^". SSfci:^'

,

^g^lffigl^M ^^MjjS

"Sp;-, . •- ,

l^_ ._.^r''

f-r.,^^ <'i.'^ K«^H^i^r!|V^'''j^SL ^^' '4

m.MSEr^

^

capital for the first time - despite its extreme conti-

nental climate and smog problem - yet its solitary

appearance as the first part of the plan was especial-

ly effective. In its simplicity it can be compared with

another Spanish building, the Sports Centre in

Cirona by Esteve Bonell and Josep Gil, which again

is an expression of the appropriate form - in this

case, the large enclosed clear-span volume - but

steering clear of tin-shed functionalism. Bonell (who

with his then partner Francesc Ruis designed the

well thought-of basketball stadium for the Barcelona

Olympics of 1992) takes the stadium trick of sinking

the arena into the ground, here cutting the volume

of the hall into the sloping site to reduce its appar-

ent volume. Placing a terrace of sloping seating

against the south-east elevation also reduces the

apparent bulk and gives an otherwise internalized

building an eye on the outside world (compare

David Morley's Indoor Cricket School at Lord's,

London, later in this section). Its flanks are relieved

by well-judged openings and canopies for escape

stairs. The resulting relatively low building, finished

in plain concrete set off with heavily veined local

golden stone, is a calm presence in the landscape.

There is always a geometric problem

involved with wrapping a building full of spectators

around a given shape of games area. At the

Colosseum in Rome, the Roman builders overcame

Design engineering in the

service of large-span enclosure:

a RAN International Architects

and Engineers (Rod Robbie

with Michael Allen), Skydome,

Toronto, 1989: Toronto skyline

b Skydome: the roof retracts in

sections

c Lobb Partnership, McAlpine

Stadium, Huddersfield,

Yorkshire, England, 1993-5

d Hellmuth, Obata -I-

Kassabaum, Hong Kong

Stadium, Hong Kong, 1991-5:

underneath the arched lattice

truss of the roof canopy

e Hong Kong Stadium:

aerial view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/contemporaryworldarchitecture-151008001113-lva1-app6891/85/Contemporary-world-architecture-404-320.jpg)

![^

mm

]

1

i M

m

fll'^'

%

^mL .7.-.3^H ^^^1

the invention of the high-speed elevator, coupled

with the progressive refinement of the steel-frame

structure. Today, the latter is no less vital than the

former, since going steadily higher not only requires

an equally steady improvement in the speed and

efficiency of vertical transport, but also demands an

increasingly stiff structure which simultaneously must

not consume too much of the floor area of the lower

regions. The higher you build, the less efficient the

net-to-gross fioorspace ratio of the entire building

tends to become, as the structure thickens towards

the point of maximum load (for services as well as

structure) at the base. Similarly, the higher you go,

the more it costs per gross square foot to build, and

the more it costs to run the finished building.

Therefore from the economic standpoint, skyscrapers

are a very strange way of achieving large amounts of

covered space - unless land is very scarce and expen-

sive indeed, and ground conditions are favourable.

Both conditions apply in rocky, sea-girt

Manhattan and to a lesser extent in lakeside

Chicago, but a financial or corporate district does not

have to be physically restricted and geologically help-

ful in order for its buildings to go high. Proximity of

the main institutions is more often what counts, and

as these expand on their historic sites, up is the only

way to go. As a we shall see, saving land is becoming

increasingly crucial for other reasons, most of them

residential as much as commercial. Finally and

inevitably, the symbolic value of the tall building -

to an institution, to a city, or to a nation - can be

sufficient to outweigh any purely financial or space

consideration. Macho it most certainly is. The femi-

nist critic Camille Paglia claimed in 1993 that it was

impossible to imagine a skyscraper designed by a

woman. Nobody contradicted her.

Primitive powered elevators were relatively

common in British factories and warehouses by

1835, transferred soon after to hotels. They were

transformed in the United States when, in 1851,

Elisha Craves Otis devised a safety brake to halt

the car if the hoisting rope broke. Confidence in

the modern elevator arrived at the New York Crystal

Palace exhibition in 1853-4, when Otis personally

cut the rope of his steam-powered elevator in the

observation tower, and visibly did not plummet to

his death. Around this time, the technology of high-

pressure water and gas pipes, and steam-heating sys-

tems, had also evolved to a point where they were

safe for use in high-rise buildings. Hydraulic power

for elevators arrived in 1870 (and was used on the

Eiffel Tower in 1889) and finally, by the turn of the

century, reliable electric power. In the late 1990s

cable-free electro-magnetic lifts, able to move later-

ally as well as vertically, are being developed, liberat-

ing towers such that they can do almost anything.

Even before this technology was adopted, the 1990s

had already seen an extraordinary outbreak of tower-

building, much of it in the Far East. The trend is

inevitably ever upwards. Moreover, it is becoming

normal for such buildings to have a layered mix of

uses - retail, offices, housing, hotels being the usual

ingredients, sometimes combined with a telecommu-

nications function - each normally requiring its own

entrance lobby at the relevant height. While mixed-

use developments can function at almost any size,

skyscrapers seems to work better on a large scale: the

different functions are stacked rather than shuffled.

Frank Lloyd Wright claimed to have

been there first, of course. He toyed intermittently

with towers all his life - the unbuilt National Life

Insurance scheme of 1924 was a stratified twenty-

five-storey tower clad in permeable copper and

glass screens - and m 1933 he conceived the idea

of a half-mile high building to house the entire

Chicago World's Fair. He conceived it as:

'a great skyscraper in which the Empire State Building

might stand free in a central interior court space ...

Instead of the old stage-props of the previous fairs,

the same old miles of picture buildings faked in

cheap materials, wrapped around a lagoon, fountain

or theatrical waterfall in the middle ... let there be,

for once, a genuine modern construction.'

After the Fair, he suggested, the tower could

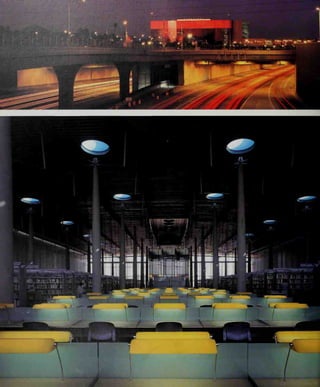

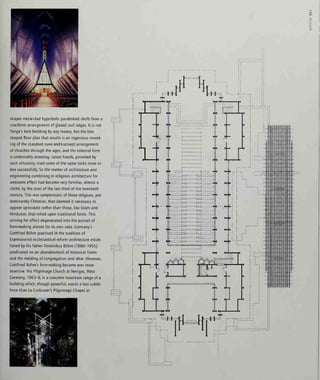

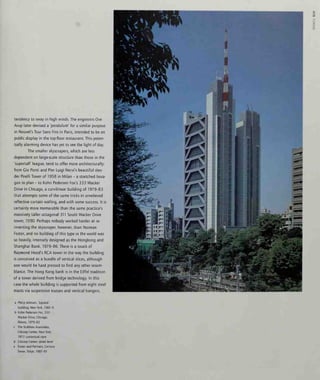

Only now are architects

beginning to come near

Wnght's prophecy of 1956:

Jean Nouvel, Tour Sans Fins,

Pans, 1989-93: model

Skidmore, Owings and Merrill

(SOM), John Hancock Center,

Chicago, 1965-70

Pel, Cobb, Freed & Partners,

Bank of China, Hong Kong,

1985-90

Frank Lloyd Wright, Mile High

Tower, Illinois, 1955](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/contemporaryworldarchitecture-151008001113-lva1-app6891/85/Contemporary-world-architecture-474-320.jpg)

![Mary and Peter Doyle

The Architecture of Mary & Peter

Doyle 1970-1990, Dublin, 1990

Andres Duany and Elizabeth

Plater Zyberk

Mohney, D, and K Easterling (eds),

Seaside: Making a New Town in

America, London, 1991

Charles and Ray Eames

Kirkham, Pat, Charles and Ray Eames:

Designers of the Twentieth Century,

Cambridge, MA, 1995

Edmond + Corrigan

Hamann, Conrad, Cities of Hope:

Australian Architecture and Design by

Edmond and Corngan, 1962-92,

Melbourne, 1993

Peter Eisenman

Eisenman Architects: Selected and

Current Works, Mulgrave, 1995;

Bedard, Jean-Fran^ois (ed). Cities of

Artificial Excavation.The Work of Peter

Eisenman 1978-1988, Montreal and

New York, 1994;

Moneo, Rafael, etal, Wexner Center

for the Visual Arts: The Ohio State

University, New York, 1989

Abdel Wahed El-Wakil

'The Mosque; Architecture of El-Wakil',

Albenaa, vol. 6, no. 34, 1987

Craig Ellwood

McCoy, Esther, Craig Ellwood,

Venice, 1968

Richard England

Abel, Chris, Transformations -

Richard England, 25 Years of

Architecture, Malta, 1987

Ralph Erskine

Egelius, Mats, Ralph Erskine, Architect,

Stockholm, 1990;

Collymore, Peter, The Architecture

of Ralph Erskine, London, 1982

Terry Farrell

Terry Farrell: Selected and Current

Works, Mulgrave, 1994;

Terry Farrell, London, 1993

Hassan Fathy

Steele, James, Hassan Fathy,

Architectural Monograph,

London, 1988;

Richards, J M, I Serageldm and D

Rastorfer; Hassan Fathy, London, 1985

Sverre Fehn

Norberg-Schultz, Christian, Sverre Fehn:

opera completa, Milan, 1997;

Fjeld, Per Olaf, Sverre Fehn:

The Thought ofConstruction,

New York, 1983

Norman Foster

Treiber, Daniel, Norman Foster,

London, 1995;

Lambot, Ian (ed), Norman Foster...

Buildings and Projects, vol. 1

,

1 964-1973,Codamnq, 1991, vol 2,

1971-1978, Hong Kong, 1990, vol. 3,

1978-1985, Hong Kong, 1990

Massimiliano Fuksas

Massimiliano Fuksas: neue Bauten und

Projekte, lunch and London, 1994

Future Systems

Pawley Martin, Future Systems -

Story of Tomorrow, London, 1993

Frank Gehry

Futagawa, Yukio (ed), Frank Cehry,

Tokyo, 1993;'

Arnell, Peter, et al, Frank Cehry:

Buildings and Projects,

New York, 1985

Bruce Coff

Saliga and Woolever, (eds), The

Architecture of Bruce Coff Munich

and New York, 1995

Teodoro Gonzalez de Leon

Heyer, Paul, Mexican Architecture:

The Work ofAbraham Zabludovsky

and Teodoro Conzalez de Leon,

New York, 1978

Michael Graves

Michael Craves; Buildings and Projects

1990-1994, New York, 1995;

Vogel Nichols, Karen, Patrick] Burke

and Caroline Hancock, Michael

Craves: Buildings and Projects

/5S2-/9S9, New Haven and

London, 1990

Allan Greenberg

Allan Creenberg, Selected Work,

London, 1995

Vittorio Gregotti

Tafuri, Manfredo, Vittono Cregotti:

progetti e architetture, Milan and

New York, 1982

Nicholas Grimshaw

Architecture, Industry and Innovation:

The Early Work of Nicholas Crimshaw

and Partners (introduction by Colin

Amery), London, 1995;

Moore, Rowan (ed). Structure, Space

and Skin, The Work of Nicholas

Crimshaw & Partners, London, 1993

Walter Gropius

Ciedion, Sigfried, Walter Cropius,

New York, 1992

Cwathmey Siegel

Cwathmey Siegel, Buildings and

Projects 1982-1992, New York, 1993

Zaha Hadid

Futagawa, Yukio (ed), Zaha Hadid.

Tokyo, 1986;

Zaha Hadid 1983-1991, El Croquis

monograph, Madrid, 1991

Hiroshi Hara

Stewart, David B and Yukio Futagawa

(eds), Hiroshi Hara. Tokyo, 1993

itsuko Hasegawa

Itsuko Hasegawa, 1993;

Itsuko Hasegawa: Recent Buildings

and Projects, Basel, 1997

Zvi Hecker

m

q

Feireiss, Kristin (ed), Zvi Hecker: die

sCD

r-

Heinz-Calinski Schule in Berim, g

Tubingen, 1996 5uX-<

John Hedjuk

Five Architects: Eisenman, Craves,

Cwathmey, Hejduk, Meier,

New York, 1972

Ron Herron

Banham, Reyner, The Visions of Ron

Herron, London, 1994

Herman Hertzberger

Herman Hertzberger: Accommodating

the Unexpected: Projects 1990- 1995,

Rotterdam, 1995

Herzog & de Meuron

Herzog & de Meuron, Tokyo, 1995;

Herzog & de Meuron, Madrid, 1993;

Wang, Wilfried, Herzog & de Meuron,

luuch. 1992;

Wang, Wilfried, Herzog & de Meuron,

Projects and Buildings 1982- 1990.

New York, 1990

Hodgetts + Fung

Hodgetts + Fung: Scenarios and

Spaces (introduction by Kurt Foster),

New York, 1997

Steven Holl

Steven Holl. Tokyo. 1996

Hans Hollein

Pettena, Giani, Hans Hollein: Works

1960-1988. Man. 1988;

Architekten Hans Hollein,

Stuttgart, 1987;

Mackler, ChrJstoph, Hans Hollein.,

Aachen, 1978;

Michael Hopkins

Davies, Colin, Hopkins: The Work of

Michael Hopkins and Partners,

London, 1993

Ingenhoven, Overdeik,

Kahlen & Partner

Hochhaus RWE AC Essen,

Dusseldorf, 1997](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/contemporaryworldarchitecture-151008001113-lva1-app6891/85/Contemporary-world-architecture-497-320.jpg)