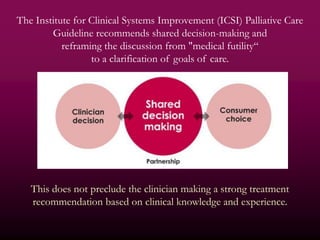

The document discusses the complexities of end-of-life decisions regarding withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining therapies, emphasizing the ethical, medical, and religio-cultural considerations. It highlights the challenges that physicians face in communicating these decisions to patients and families, as well as the importance of shared decision-making based on clear understanding and goals of care. Cultural backgrounds significantly affect preferences related to end-of-life discussions, necessitating individualized approaches in treatment decision-making.