This document describes a Ph.D. thesis that studied the seismic response of an instrumented multi-story reinforced concrete building in India. Acceleration time histories recorded in the building during the 2001 Bhuj earthquake are analyzed to determine modal parameters, floor accelerations and velocities, storey drifts, and other response quantities. Ambient vibration tests are conducted to identify the building's modal properties. Soil properties at the site are determined through in-situ and laboratory tests. Finite element models of the building with different levels of complexity are developed and analyzed under earthquake ground motions, both with and without considering soil-structure interaction effects. The observed and computed responses are then compared.

![xxiii

NOMENCLATURE

CHAPTER 3 - STRUCTURAL RESPONSE OF THE INSTRUMENTED

BUILDING FROM STRONG MOTION RECORD

EW East west direction

NS North south direction

Afloor Peak value of acceleration recorded at the concern floor level

AG Peak value of acceleration recorded at the ground floor level

NS1 First translational frequency in N-S direction

EW1 First translational frequency in E-W direction

T1 First torsional frequency

NS2 Second translational frequency in N-S direction

T2 Second torsional frequency

CHAPTER 4 - IDENTIFICATION OF MODAL PARAMETERS OF THE

INSTRUMENTED BUILDING FROM AMBIENT VIBRATION

RECORDS

t, τ Time

f Frequency

y(t) System response

,ϕ Mode shape, mode shape matrix

C Covariance matrix

G Spectral density matrix

u, U Singular vector, Matrix of singular vectors

[ ]is Diagonal matrix of singular values

CHAPTER 5- DETERMINATION OF INSITU SOIL PARAMETERS OF

FOUNDING SOIL OF THE INSTRUMENTED BUILDING

DS Disturbed soil sample

UDS Undisturbed soil sample

SPT Standard penetration test

SBC Safe bearing capacity

NP Non plastic

DST Direct shear test

LL Liquid limit

PL Plastic limit

PI Plasticity index](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/e06007d8-aa31-45d6-8e33-b25ea132ae82-150903142754-lva1-app6891/85/Complete-Thesis-29-320.jpg)

![3.27

3.13 whereas second mode is a torsional having natural frequency of 1.031 Hz. Detailed

study of different FE models of the building and their response to Bhuj earthquake have

been studied in Chapter 6 and 7.

Table 3.13: Modal frequencies of bare frame model

Mode M1 (Hz)

1 0.909 First translational mode in NS direction

2 1.031 First torsional mode

3 1.084 First translational mode in EW direction

4 1.582 Mixed mode

5 1.841 Mixed mode

3.7 ANALYSIS OF TIME HISTORIES FOR BUILDING RESPONSE, RESULT

AND DISCUSSION

3.7.1 Fourier Spectrum

A Fourier spectrum is a plot where Fourier amplitude (response of the linear

system) is extracted from the recorded signal, plotted against the frequencies of

excitation. Linear transforms, especially Fourier is widely used in solving problems in

science and engineering, which provides a link between the time domain and the

frequency domain of the signal. The Fourier transform is used in linear systems analysis

(Brigham, 1988). Although measurement data are usually available as samples of the

input and output time signals, it is very useful to look at the frequency-domain

representation of these signals. Many interesting signal’s features are revealed in

frequency domain. For instance, the Eigen frequencies of a structure emerge immediately

as the peaks in a frequency-domain plot of a measurement signal.

The mathematical tool to convert a time signal to the frequency domain is the

Fourier transform. Fourier transform of the accelerogram )(tx&& is given by Eq. (3.14).

∫

∞

∞−

ω−

=ω dtetxX ti

)()( && (3.14)

Assuming ground acceleration is non-zero in ],0( Tt ∈ the Eq. (3.14) can be written as](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/e06007d8-aa31-45d6-8e33-b25ea132ae82-150903142754-lva1-app6891/85/Complete-Thesis-77-320.jpg)

![3.32

record is obtained for the Ch.12 to Ch.8 by deducting the GF component of Ch.6. For

vertical component, Ch.14 is obtained by deducting Ch.13 from it.

The relative acceleration time histories obtained as described earlier have been

used as input for modal parameter extraction. Acceleration time history of the remaining

floors where there is no instrumental data is linearly interpolated. All floors are assumed

as rigid diaphragms and nodes where acceleration time histories are measured have been

considered as master nodes. The equations of other floor nodes have been obtained using

master nodes movement. To minimize the effect of noise in records, 200 SPS data is

decimated by a factor of two to have ultimate data of 100 SPS or having nyquist

frequency of 50Hz. Table 3.14 gives modal parameters of the instrumented building

based on strong motion records of Bhuj earthquake.

Table 3.14. Modal parameters estimated from strong motion data

Mode Frequency (Hz) Period (s) Damping Ratio (%)

1 1.26NS1

0.79 5.0

2 1.47EW1

0.68 2.9

3 2.34T1

0.43 2.7

4 3.91NS2

0.26 2.4

5 4.98T2

0.20 1.4

3.7.4 Short Time Fourier Transform (STFT)

In order to identify variation in the first two fundamental system frequencies over

the whole duration of earthquake, instantaneous system frequency was evaluated by

STFT as described in Trifunac et al. (2001). Apparent building rocking responses for the

EW and NS were evaluated as:

[ ] 30/)t(a)t(a)t( 712WE

..

−=θ − (3.22)

[ ] 30/)t(a)t(a)t( 16SN

..

−=θ − (3.23)

Where ai indicates the accelerations of sensor i and 30 is the building height in metre (see

Fig. 3.15 for sensor locations).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/e06007d8-aa31-45d6-8e33-b25ea132ae82-150903142754-lva1-app6891/85/Complete-Thesis-82-320.jpg)

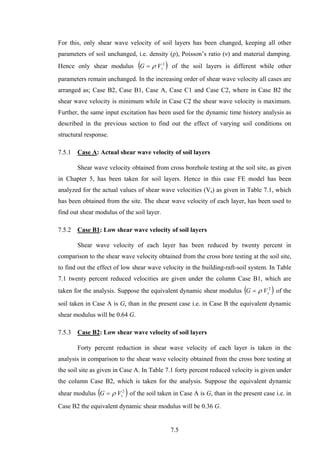

![4.7

Thus if the modal co-ordinates are un-correlated, the power spectral density matrix

( )fqqS of the modal co-ordinates is diagonal, and thus, if the mode shapes are orthogonal,

then Eq. (4.4) is a singular value decomposition (SVD) of the response spectral matrix.

Therefore, FDD is based on taking the SVD of the spectral density matrix

( ) ( )[ ] ( )T

iyy tsff UUG = (4.5)

The matrix [ ]...,u,uU 21= is a matrix of singular vectors and the matrix [ ]is is a diagonal

matrix of singular values. As it appears from this explanation, plotting the singular values

of the spectral density matrix will provide an overlaid plot of the auto spectral densities of

the modal coordinates. Note here that the singular matrix [ ]...,u,uU 21= is a function of

frequency because of the sorting process that is taking place as a part of the SVD

algorithm. A mode is identified by looking at where the first singular value has a peak, let

us say at the frequency 0f . This defines in the simplest form of the FDD technique - the

peak picking version of FDD - the modal frequency. The corresponding mode shape is

obtained as the corresponding first singular vector 1u in U .

( )01u f=ϕ (4.6)

For modal damping, enhanced FDD technique is used as described in Brincker et al.

(2000).

The modal damping is estimated using Enhanced FDD (EFDD) technique, which

is an extension to the FDD technique. In EFDD, the SDOF Power Spectral Density

function, identified around a resonance peak, is taken back to the time domain using the

Inverse Discrete Fourier Transform (IDFT). The damping is obtained by determining the

logarithmic decrement of the corresponding SDOF normalized auto correlation function.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/e06007d8-aa31-45d6-8e33-b25ea132ae82-150903142754-lva1-app6891/85/Complete-Thesis-129-320.jpg)

![5.7

5.4.1 Test Procedure

The boreholes, for conducting the cross borehole tests, had an internal diameter of

80 mm. and were made upto a depth of 30m below the natural ground level. These

boreholes were cased with PVC casing pipes and plugged at the bottom. PVC pipes

should withstand pressure upto 10kg/cm2

(IS: 4985 - 2000). The water inside the

boreholes was pumped out before conducting the test. Holes in alluvium soil close in

soon after digging and to prevent collapse or washouts, boreholes are normally cased with

plastic PVC pipe. The annular space between the casing and the surrounding soil has been

filled with 10 gallons of water per bag of cement, diluted with 5 to 10% bentonite by

volume [C., Doug, (2002)] to ensure a proper coupling of the soil with the borehole

casing.

A set of three boreholes laid out along a straight line, was used for conducting the

test as shown in Fig. 5.6. The spacing, centre to centre, between the first and second

boreholes was 4.88m and between the second and third boreholes it was 4.93m.

A schematic diagram of the cross borehole test setup is given in Fig.5.7. A Bison

borehole hammer was now lowered into the first borehole (borehole No. 1). This is a

special type of hammer with hydraulically operated shoes that can be extended or

retracted within the borehole as desired. At a predetermined depth, say 3.0m, the hammer

shoes were hydraulically extended to grip the borehole walls and lock the hammer in

place. Now two geophones were lowered into the other two boreholes (boreholes No. 2

and 3). These geophones with specially fitted rubber bladders, which can be inflated

pneumatically, can be locked in the borehole at any desired depth, 3.0m in this case. The

electrical signals from the borehole hammer and the geophones were fed into a Bison

seismograph (Fig. 5.8).

Having locked the borehole hammer and the geophones at the same desired depth,

3.0m in this case, the seismograph was switched on. A shear wave was now generated in

the first borehole by operating the hammer. This activated a timer switch in the

seismograph and the shear wave waveform arrivals at the borehole geophones were

displayed on the video screen of the seismograph. Figure 5.9 shows a typical record

obtained from the cross borehole test using superposition of waveforms and Fig. 5.10 shows](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/e06007d8-aa31-45d6-8e33-b25ea132ae82-150903142754-lva1-app6891/85/Complete-Thesis-157-320.jpg)

![6.6

6.4.1 Input excitation

Strong motion record at the ground floor in NS, EW and vertical directions of the

building is used as input excitation at the base of FE models for the dynamic time history

analysis. The frequency contents of input excitation in three perpendicular directions are

shown in Figs. 6.4 (a), 6.4 (b) and 6.4 (c). The characteristics of input excitation in three

perpendicular directions are given in Table 6.2.

Table 6.2: Characteristics of input excitation

Direction Peak acceleration

(m/s2

)

Time of occurrence of peak

acceleration (s)

NS 1.038 46.940

EW 0.782 34.945

Vertical 0.686 44.060

6.4.2 Material damping

The material damping of the reinforced concrete structure of the instrumented

multi-storied reinforced concrete building (G +9) is incorporated as Raleigh damping:

[ ] [ ] [ ]KMC β+α= (6.6)

Where α and β are Raleigh damping coefficients. The damping matrix [ ]C is orthogonal

with respect to system eigenvectors, and the modal damping coefficients Ci for the ith

mode may be calculated:

2

iiii 2C ωβ+α=ωξ= (6.7)

above equation (2) can be written in terms of modal critical ratio:

( ) 2/2/ iii ωβωαξ += (6.8)

The value of α and β are computed by using the first and second modal frequencies (i = 1,

2) with equation (3).

In the instrumented multi-storied reinforced concrete building (G +9) five percent

modal damping is observed in the first mode of the building in the earthquake from the

response of building to earthquake as described in Chapter 3. Therefore for the dynamic

time history analysis in the present study, five percent modal damping is considered for

the first two modes of the building to calculate values of α and β coefficients to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/e06007d8-aa31-45d6-8e33-b25ea132ae82-150903142754-lva1-app6891/85/Complete-Thesis-178-320.jpg)

![7.10

7.7 MATERIAL DAMPING

The damping in the raft-soil-structure system includes material damping and the

radiation damping. The material damping has been incorporated as Raleigh damping:

[ ] [ ] [ ]KMC β+α= (5.1)

Where α and β are Raleigh damping coefficients. The damping matrix [ ]C is orthogonal

with respect to system eigenvectors, and the modal damping coefficients for the ith

mode

Ci may be calculated:

2

iiii 2C ωβ+α=ωξ= (5.2)

above equation (2) can be written in terms of modal critical ratio:

( ) 2/2/ iii ωβωαξ += (5.3)

The value of α and β are computed by using the first and second modal frequencies (i = 1,

2) with equation (3).

In the instrumented multi-storied reinforced concrete building (G +9) five percent

modal damping is observed in the first mode of the building during Bhuj earthquake as

mentioned in Chapter 3. Therefore for the dynamic time history analysis of building-raft-

soil system, five percent modal damping is considered for the first two modes to calculate

values of α and β coefficients to incorporate the Raleigh damping in the building-raft-soil

system. Material damping is assumed to be constant throughout the entire seismic event,

although the damping ratio varies with the strain level.

7.8 TYPE OF ANALYSIS PERFORMED ON THREE-DIMENSIONAL SOIL-

RAFT-BUILDING SYSTEM

Dynamic time history analysis has been performed using the comprehensive

building-raft-soil system. Input base excitation described in the next section, has been

applied at the bottom of the soil block in the FE model of the building for the whole

duration of the recorded Bhuj earthquake (133.525 s).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/e06007d8-aa31-45d6-8e33-b25ea132ae82-150903142754-lva1-app6891/85/Complete-Thesis-208-320.jpg)