This document discusses different historical perspectives on the origins of the Cold War between 1945-1991. It begins by providing context for rising tensions between former World War 2 allies the US and USSR. It then outlines the traditional, revisionist, and post-revisionist views that emerged in the West. The traditional view blamed Soviet intransigence, while the revisionist view saw US economic imperialism as the cause. The post-revisionist view argued it was a complex interaction between both sides. Soviet views also evolved over time from solely blaming US imperialism to more nuanced accounts after Stalin's death.

![Post-Soviet interpretation

The orthodox Soviet postion on the origins of the

Cold War from the early 1950s through to 1988

was that it came about as a result of US

imperialism. This perspective is clearly stated, for

example, in the works of Nikolai Inozemtsev,

Director of the Moscow Institute of World

Economy and International Relations. Here,

however, is a view from two younger Russian

historians, now working in the USA, who grew up

and were educated in the Soviet Union and both

worked at the Institute of US and Canada Studies

in Moscow until the mid-1990s.

“Stalin wanted to avoid confrontation

with the West [because he] believed in

the inevitability of a postwar economic

crisis of the capitalist economy and of

clashes within the capitalist camp that

would provide him with a lot of space for

geopolitical manoeuvering in Europe and

Asia – all within the framework of

general cooperation… Stalin’s postwar

foreign policy was more defensive,

reactive and prudent than it was the

fulfilment of a master plan. Yet instead

of postponing a confrontation with the

United States …he managed to draw

closer to it with every step.”

Vladislav Zubok and Constantin

Pleshakov, Inside the Kremlin’s Cold

War: From Stalin to Khrushchev,

(Cambridge MA, 1996)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-6-320.jpg)

![From wartime alliance to a war of nerves (1945-1946)

As the Norwegian historian, Odd Arne Westad, has pointed out, the USA, the USSR

and Great Britain were “accidental allies in a global war brought on by their mutual

enemies”. [The Alliance] “did not consist of a long period of working together for

common aims, as most successful alliances do. It was a set of shotgun weddings

brought on by real need, at a time when each of them had to find help to defeat

immediate threats.” (The Cold War: A World History, Penguin Random House, London

2017, pp.43-44). In Section 2 of our module on The Cold War, Andrea Scionti has

highlighted the tensions that existed between the allies during the war and these

carried over into the period 1945–1948. Nevertheless, at the end of the war political

or military confrontation was not uppermost in the minds of the political elites in

London, Moscow or Washington. Each of the allies was confronted by major domestic

political and economic issues and while Britain and the USA were seeking to stabilise

the situation in war-torn Europe, the Soviet Union needed to concentrate on

consolidating its position in eastern and south-eastern Europe. However, at this stage

there were still some signs of willingness on both sides to cooperate. This included

the founding of the United Nations, the establishment of the UN Atomic Energy

Commission and cooperation in the development of the UN Universal Declaration of

Human Rights. But by the end of 1947 the necessity and the will to cooperate no

longer existed.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-7-320.jpg)

![The chances of revolution in Eastern

Europe

Not surprisingly, in 1945-47 world revolution

was very low on the USSR’s list of priorities.

Indeed, Stalin did not even anticipate that

Eastern Europe, now liberated by the Red

Army, was ripe for home-grown revolution

[See his comment to Roosevelt’s envoy, Harry

Hopkins, in 1944]. In the immediate post-war

years the Red Army was still fighting anti-

Soviet resistance groups in the Baltic States,

Belarus, Poland, Romania and Ukraine. In

most of Eastern Europe in the 1930s

communist parties had been banned and

their leaders imprisoned. At this stage

Stalin’s preference was for the Communist

Party in these countries to go into coalition

with other non-Fascist parties until such time

as conditions favoured a communist takeover

of power. According to the historian Anne

Applebaum, Stalin’s foreign minister in 1944

thought this might take 30-40 years. [Iron

Curtain, London 2013, p.xxx]

Harry Hopkins (left) at the Livadia Palace, Crimea,

Feb.1945 with tewo other members of the team.

US National Archives & Records Administration Public Domain

In a meeting in Moscow to plan the Yalta

Conference in February 1945, Harry

Hopkins, President Roosevelt’s envoy,

recorded that when he asked Stalin about

the Soviet Union’s intentions towards

Poland, Stalin offered this blunt response:

“Communism would fit Poland as a saddle

on a cow.”

Quoted by Adam Ulam, Understanding the Cold

War, (New York 2002) p.277.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-10-320.jpg)

![US public opinion regarding the

intentions of the Soviet Union in 1945.

Before the United States entered the war in

1941 the majority of Americans were strongly

anti-Communist. It took all of President

Roosevelt’s considerable persuasive powers

to convince American public opinion that the

Soviet Union were allies that could be

trusted. Indeed, he encouraged the mass

media to refer to Stalin as ‘Uncle Joe’ and

actively encouraged Hollywood to make pro-

Soviet films such as Mission to Moscow, North

Star and Song of Russia.

However, by the time of the Potsdam

Conference American public opinion was

calling for ‘our boys to come home’ and was

much more sceptical about the Soviet Union’s

foreign policies. The Administration had to

strike a balance between acknowledging the

public’s concerns while encouraging them to

believe that an internationalist policy was

the best approach to keeping Soviet

expansionism in check.

George Kennan, the diplomat who had

written the Long Telegram which strongly

influenced US post-war policy towards

the Soviet Union, returned to Washington

in 1946 and was sent on a speaking tour

of the US in the spring to assess public

opinion. Years later he recalled his

impressions of that tour:

“[M]uch of American opinion..was at that

time bewildered and uncertain. People

had been persuaded for years by our

government that the peoples and

government of the Soviet Union were

great and noble allies. Now, contrary

reports and opinions were beginning to

be heard [and] had already begun to

make people wonder whether the Soviet

regime was quite what they had been

encouraged to believe it to be.”

Letter to his biographer, John Lukacs,

December 1995 reprinted in American

Heritage, Vol.46, no.8 1995](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-15-320.jpg)

![Extracts from the Kennan ‘Long Telegram’ to explain

the thinking behind Soviet foreign policy

Kennan began by explaining that Russian rulers have always feared contact and

foreign penetration:

“At bottom of Kremlin's neurotic view of world affairs is traditional and instinctive

Russian sense of insecurity…”

“Internal policy [is] devoted to increasing in every way strength and prestige of Soviet

state: intensive military-industrialization; maximum development of armed forces;

great displays to impress outsiders; continued secretiveness about internal matters,

designed to conceal weaknesses and to keep opponents in dark….”

“Russians will participate officially in international organizations where they see

opportunity of extending Soviet power or of inhibiting or diluting power of others….”

“Toward colonial areas and backward or dependent peoples, Soviet policy..will be

directed toward weakening of power and influence and contacts of advanced Western

nations…[to create] a vacuum which will favor Communist-Soviet penetration...”

Kennan anticipated a major propaganda war by the Soviets targeted on the West:

“To undermine general political and strategic potential of major western powers: poor

will be set against rich, black against white, young against old, newcomers against

established residents….”

“Everything possible will be done to set major Western Powers against each other...”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-27-320.jpg)

![Winston Churchill calls for a US-UK

partnership against Soviet expansion

Westminster College, Missouri holds an

annual lecture to promote international

relations. In 1946 the guest lecturer was

Winston Churchill, who was no longer in

power in the UK. In the presence of President

Truman, he called for a US-UK partnership to

halt the expansion of Soviet influence.

Winston Churchill and President Truman on the train

to Fulton, Missouri before Churchill gave his speech

at Westminster College, Missouri, 5 March 1946.

Missouri State Archives

No known restrictions on use

Extracts from Winston Churchill’s

‘Sinews of Peace’ [or Iron Curtain]

speech

“From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the

Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended

across the continent. Behind that line lie all

the capitals of the ancient states of central

and eastern Europe. Warsaw, Berlin, Prague,

Vienna, Budapest, Belgrade, Bucharest and

Sofia… and all are subject…to a very high

and increasing measure of control from

Moscow….”

“I do not believe that Soviet Russia desires

war. What they desire is the fruits of war

and the indefinite expansion of their power

and doctrines. But what we have to consider

here today while time remains, is the

permanent prevention of war and the

establishment of conditions of freedom and

democracy as rapidly as possible in all

countries. Our difficulties and dangers will

not be removed by closing our eyes to them.

They will not be removed by mere waiting

to see what happens; nor will they be

removed by a policy of appeasement… I am

convinced that there is nothing they admire

so much as strength, and there is nothing

for which they have less respect than for

military weakness.”

Congressional Record, 79th Congress, 2nd session,

A1146-7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-29-320.jpg)

![Josef Stalin’s reply to Winston Churchill’s

“iron curtain” speech

Extract from Stalin’s response in Pravda

to Churchill’s ‘iron curtain’ speech:

“Interviewer: What is your opinion of Mr

Churchill’s latest speech in the United

States of America?

Stalin: I regard it as a dangerous move,

calculated to sow the seeds of dissension

among the Allied states and impede their

collaboration.

Interviewer: Can it be considered that Mr

Churchill’s speech is prejudicial to the cause

of peace and security?

Stalin: Yes, unquestionably. As a matter of

fact, Mr Churchill now takes the stand of

the warmongers, and in this Mr Churchill is

not alone. He has friends not only in Britain

but in the United States of America as

well….The Germans made their invasion

through Finland, Poland, Romania, Bulgaria

and Hungary…And so what can there be

surprising about the fact that the Soviet

Union, anxious for its future safety, is trying

to see to it that governments loyal in their

attitude to the Soviet Union should exist in

these countries? How can anyone, who has

not taken leave of his senses, describe these

peaceful aspirations of the Soviet Union as

expansionist?”

Pravda, 13 March 1946 (translation)

Marshal Stalin was quick to respond to

Churchill’s ‘iron curtain’ speech. This

interview was published in Pravda [then the

official newspaper of the Communist Party]

on 13 March 1946. He labelled Churchill as a

warmonger and denied that Soviet policy

regarding central and eastern Europe was

expansionist. It was vital to soviet security

that they should regard the region as a

sphere of influence.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-30-320.jpg)

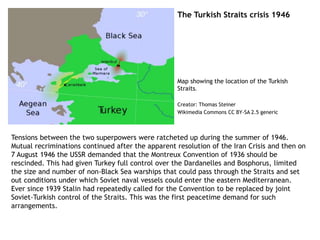

![The Turkish Straits crisis 1946

The Potsdam Agreement in 1945 had included

a clause confirming the right of the USSR to

seek a revision of the Montreux Convention.

However, the mood in Washington had

changed since then and this was now seen as

a move on Moscow’s part that would lead

inevitably to Soviet control of Turkey, then

Greece and eventually the whole eastern

Mediterranean (an early statement of what

came to be known as the “Domino theory”).

This source, a memorandum from the US

Secretaries of State, War and the Navy makes

the US position regarding the Turkish Straits

very clear. It went on to assert that: “the

best hope of peace” was that “the United

States would not hesitate to join other

nations in meeting armed aggression by the

force of American arms.”

[We] “feel that it is in the vital interests

of the United States that the Soviet

Union should not by force or through

threat of force succeed in its unilateral

plans with regard to the Dardanelles and

Turkey. If Turkey under pressure should

agree to the Soviet

proposals, any case which we might later

present in opposition to the Soviet plan

before the United Nations or to the

world public

would be materially weakened; but the

Turkish Government insists that it has

faith in the United Nations system and

that it will resist

by force Soviet efforts to secure bases in

Turkish territory even if Turkey has to

fight alone. While this may be the

present Turkish

position, we are frankly doubtful

whether Turkey will continue to adhere

to this determination without assurance

of support from the United States.”

Memorandum to the US President from

the Secretaries of State, War and the

Navy, 15 August 1946.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-35-320.jpg)

![The British government informs the US

State Department that it will withdraw

its troops and financial support from

Greece within six weeks

During the war Greece, Turkey and the eastern

Mediterranean was seen as a British sphere of

influence. In 1944, after Greece was liberated

from Geman occupation a civil war broke out.

Left-wing resistance groups formed the National

Liberation Front which gradually came under the

control of the communists. The British backed

the right-wing forces and a government was put

in place. By spring 1945 the left had been

crushed by a coalition of government and British

forces. But hostilities broke out again in early

1946 and the British found themselves

increasingly involved in supporting the Greek

government, militarily and financially. On 21

February 1947, the British Government sent two

diplomatic notes to Washington, one relating to

Greece and the other to Turkey, stating that,

due to domestic economic difficulties, all British

military and economic assistance would end on

31 March.

In 1946 Joseph M. Jones was special

assistant to Dean Acheson, US

Undersecretary of State. He was

present in the State Department when

the British diplomatic notes were

presented and recorded the contents:

“In total Greece needs in 1947 between

£60 million and £70 million [equivalent

to $240 to $280 million at that time] in

foreign exchange and for several years

thereafter…..But Great Britain would be

unable to offer further financial

assistance after March 31. The British

Government hoped the United States

would be able to provide enough aid to

enable Greece to meet its minimum

needs, civilian and military, assuming as

of April 1 the burden theretofore borne

chiefly by Great Britain.”

Cited in Joseph M. Jones, The Fifteen

Weeks, Viking Press, New York 1955

pp.5-6.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-42-320.jpg)

![Greece: the trigger that led to the

Truman Doctrine and an escalation of

tension between the US and the USSR

In the absence of Acheson and the

Secretary of State George C. Marshall,

the British diplomatic notes were

received by John Hickinson, Director of

the Office of European Affairs in the

State Department. He observed that at

that moment Britain had “handed the job

of world leadership, with all its burdens

and all its glory, to the United States”.

[Jones, Fifteen Hours, p.7]

Undersecretary of State Acheson was

later to comment directly to President

Truman that this was “the most major

decision with which we have been faced

since the war”. On 27 February 1947 he

made a report to Truman in which he

spelt out the dangers if the United States

did nothing about the Greek situation.

Extract from a Briefing by Dean

Acheson to President Truman and other

advisers on 27 February 1947:

“In the past eighteen months, Soviet

pressure on the Straits, on Iran, and on

northern Greece had brought the Balkans

to the point where a highly possible

Soviet breakthrough might open three

continents to Soviet penetration. Like

apples in a barrel infected by one rotten

one, the corruption of Greece would

infect Iran and all to the east. It would

also carry infection to Africa through Asia

Minor and Egypt, and to Europe through

Italy and France, already threatened by

the strongest domestic Communist

parties in Western Europe. The Soviet

Union was playing one of the greatest

gambles in history at minimal cost. It did

not need to win all the possibilities. Even

one or two offered immense gains. We

and we alone were in a position to break

up the play.”

Source: Dean Acheson, Present at the Crreation: My

Years in the State Department, New York, Norton

1969, p.219](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-43-320.jpg)

![The Soviet response to the American position on Greece in 1947

Perhaps because the US had treated Greece as a

part of the British sphere of influence, the US

State Department’s knowledge of what was

happening in Greece was sketchy. The

interpretation provided by Dean Acheson, which

strongly influenced Truman’s thinking,

perpetuated a myth about the Greek Civil War

within the Truman Administration that the Greek

Communists were receiving aid from the Soviet

Union as part of a planned expansion in the

region. In fact the assistance the Greek

communists were getting was from the Yugoslavs

and Albanians. This was contrary to Stalin’s

orders.

When Stalin and Churchill had met in Moscow in

October 1944 they had made the so-called

“percentages agreement”. They agreed that

Britain would have 90% influence in Greece in

return for the USSR having 90% influence in

Romania and 75% in Yugoslavia. According to

American historian, W.H. MacNeill, “there is no

evidence that Stalin ever reneged on this

commitment and aided the Greek Communist

movement.” [W.H. McNeill, The Greek Dilemma,

Philadelphia 1947, p.145]

The Greek Civil War was seen by some

communists in other parts of West

Europe as a possible model for them.

But, as Arne Westad has observed, Stalin

took a very different view:

“The Greek disaster led Stalin to demand

that other communists from China to

Italy, not act prematurely….they had

neither the experience nor the

theoretical understanding to take and

keep power on their own. Only when

they were guided by the Soviet Union and

protected by the Red Army [as in Eastern

Europe] would they stand a chance of

permanently defeating their enemies.”

O.A. Westad, The Cold War: A World

History (London 2017) p.76](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-44-320.jpg)

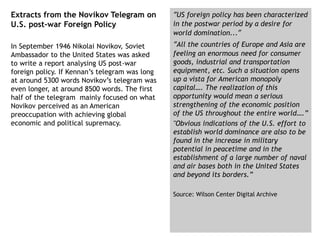

![It took Congress two months to pass the

legislation which released the $400 million to

support Greece and Turkey. Most historians see

this moment as the de facto beginning of the Cold

War. Undoubtedly, it is possible to see the

beginnings of a US foreign policy based on

‘containment’ in this speech. Essentially, to

persuade Congress to agree to release $400

million in aid, Truman had to persuade them that

American security required intervention to

prevent the expansion of Communism wherever in

the world it occurred. This was a significant shift

in mindset from a foreign policy based mainly on

the principle of defending US’ interests within the

Western Hemisphere (i.e. North and South

America and the surrounding waters]. However,

as the British historian, Martin Folly, observes, it

took around 18 months, following the 12 March

1947 speech, for the policy of containment to

fully evolve, and the aim was to use economic

measures to bring about internal collapse within

the Soviet system, rather than a costly war.

The Truman Doctrine

“Over the eighteen months following

the Truman Doctrine speech, Truman’s

attitude coalesced in the face of

Soviet responses, which were all now

read in Washington to show that the

Soviet Union was driven by limitless

ambitions to dominate the globe but

would use subversion and other

indirect methods in preference to

open military action. There was no

negotiating with such a power, the

only language that it understood was

strength.”

Martin Folly, Harry S. Truman, in Oxford

Encyclopedia of American Military and

Diplomatic History, [Oxford 2013] p.381](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-46-320.jpg)

![The Truman Doctrine

It took Congress two months to pass the

legislation which released the $400 million to

support Greece and Turkey. Most historians see

this moment as the de facto beginning of the

Cold War. Undoubtedly, it is possible to see the

beginnings of a US foreign policy based on

‘containment’ in this speech. Essentially, to

persuade Congress to agree to release $400

million in aid, Truman had to persuade them

that American security required intervention to

prevent the expansion of Communism wherever

in the world it occurred. This was a significant

shift in mindset from a foreign policy based

mainly on the principle of defending US’

interests within the Western Hemisphere (i.e.

North and South America and the surrounding

waters]. However, as the British historian,

Martin Folly, observes, it took around 18 months,

following the 12 March 1947 speech, for the

policy of containment to fully evolve, and the

aim was to use economic measures to bring

about internal collapse within the Soviet system,

rather than a costly war.

“Over the eighteen months following the

Truman Doctrine speech, Truman’s

attitude coalesced in the face of Soviet

responses, which were all now read in

Washington to show that the Soviet Union

was driven by limitless ambitions to

dominate the globe but would use

subversion and other indirect methods in

preference to open military action.

There was no negotiating with such a

power, the only language that it

understood was strength.”

Martin Folly, Harry S. Truman, in Oxford

Encyclopedia of American Military and

Diplomatic History, [Oxford 2013] p.381](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-47-320.jpg)

![The influence of the USSR on its eastern

European neighbours is decisive

In Moscow the leadership mistrusted the

motives behind the Plan and were concerned

that aid to eastern European states would

undermine its influence there.

Representatives of 22 European governments

were invited to meet in Paris on 12th July

1947 to discuss participation in the European

Recovery Program. The Soviet Union was not

included. Czechoslovakia, Poland and

Hungary were keen to participate, Bulgaria

and Albania expressed an interest and only

Yugoslavia and Romania in eastern Europe

sought Moscow’s advice. By 9 July Bulgaria

and Yugoslavia had decided not to attend,

Czechoslovakia and Hungary came to the

same conclusion a day later and on 11 July

Albania, Finland, Poland, and Romania

followed suit.

Jan Masaryk (right) and Laurence Steinhardt, US

Ambassador, September 1947

Wikimedia Commons public domain

On 8 July 1947 Czech premier Gottwald and

Foreign Minister Masaryk were summoned to

Moscow and forcibly told not to participate in

the Paris meeting. On their return to Prague

Gottwald recorded: “[Stalin] reproached me

bitterly for having accepted the invitation to

participate in the Paris Conference. He does

not understand how we could have done it. He

says we have acted as if we were ready to turn

our back on the Soviet Union.”

Masaryk remarked: “I went to Moscow as the

foreign minister of an independent sovereign

state. I returned as a lackey of the Soviet

government.”

E. Taborsky, Communism in Czechoslovakia,

Princeton 1961, p.20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-51-320.jpg)

![“The so-called Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan are

particularly glaring examples of the manner in which the

principles of the United Nations are violated, of the way in which

the organization is ignored…”

“…the United States government has moved towards a direct

renunciation of the principles of international collaboration and

concerted action by the great powers and towards attempts to

impose its will on other independent states, while at the same

time obviously using the economic resources distributed as relief

to individual needy nations as an instrument of political

pressure. […]

It is becoming more and more evident to everyone that the

implementation of the Marshall Plan will mean placing European

countries under the economic and political control of the United

States and direct interference by the latter in the internal

affairs of those countries.

Moreover, this plan is an attempt to split Europe into two camps

and, with the help of the United Kingdom and France, to

complete the formation of a bloc of several European countries

hostile to the interests of the democratic countries of Eastern

Europe and most particularly to the interests of the Soviet

Union.”

Soviet deputy foreign minister Andrei Vyshinsky, Speech to the

UN General Assembly, 18 September 1947.

Source: Jussi M. Hanhimäki and Odd Arne Westad (eds.), The Cold

War: A History in Documents and Eyewitness Accounts, 126-128.

The Soviet reaction to

the Marshall Plan

By September 1947 the

Kremlin had completed its

move from being cautiously

positive about the Marshall

Plan in mid-June to openly

hostile. Their position was

clearly stated at the United

Nations on 18 September,

1947 by Andrei Vyshinsky,

Deputy Foreign Minister

and Soviet spokesperson at

the UN. He accused the US

of using the Marshall Plan

to impose political pressure

through economic means,

explicitly labelling it an

aggressive move on

Truman’s part.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-52-320.jpg)

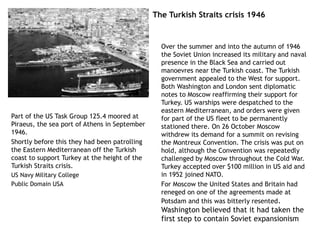

![The “X article”

The third component in the evolution of US

foreign policy after the Truman Doctrine speech

and the Marshall Plan was the idea of

containment. On 4 July 1947 an article titled

“The Sources of Soviet Conduct” appeared in

the influential Foreign Affairs magazine under

the pseudonym “X”. The author was later

revealed to be George Kennan, the author of the

Long Telegram. It had originally been produced

as an internal report for Secretary of the Navy,

James Forrestal, who received it in January

1947. By the time that it appeared in the

Foreign Affairs magazine many officers within

the Truman Administration were familiar with its

main arguments.

While restating some of the points made in the

Long Telegram and in the evidence he had

provided for the Clifford-Elsey Report, Kennan

was now spelling out the logic behind a long-

term, patient but firm policy of containing the

Soviet Union’s expansionism. Indeed this was the

first time the word ‘containment’ had been used

in relation to US foreign policy. Kennan later

stressed that he had been misinterpreted by US

policymakers who emphasised military

containment when he was talking about

containment through diplomatic and economic

means.

“The main element of any United States

policy toward the Soviet Union must be a

long-term, patient but firm and vigilant

containment of Russian expansive

tendencies. [...] Soviet pressure against the

free institutions of the Western world is

something that can be contained by the

adroit and vigilant application of

counterforce at a series of constantly

shifting geographical and political points,

corresponding to the shifts and manœuvres

of Soviet policy, but which cannot be

charmed or talked out of existence.”

X (George F. Kennan), “The Sources of Soviet

Conduct”, Foreign Affairs 25 n. 4 (July 1947),

pp.575-76.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-53-320.jpg)

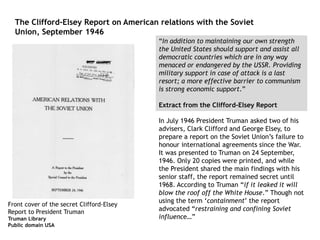

![The Cominform

In response to American initiatives, the

Soviet Union promoted its own initiatives to

increase the coordination between

communist parties. On 5 October 1947, at a

conference in the Polish city of Szklarska

Poręba, the Communist Information Bureau

(Cominform) was created. Stalin had called

the meeting in part to respond to the

different positions among Eastern European

governments about participating in the

Marshall Plan.

The Cominform included seven Eastern bloc

communist parties (USSR, Czechoslovakia,

Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania and

Yugoslavia, which was expelled the following

year after the Stalin-Tito break). The French

and Italian communist parties were also

invited to join, and specifically tasked with

obstructing the implementation of the

Marshall Plan and the Truman Doctrine in the

Western bloc.

“The need for mutual consultation […] has

become particularly urgent at the present

juncture when continued isolation may lead

to a slackening of mutual understanding,

and at times, even to serious blunders.

In view of the fact that the majority of the

leaders of the Soviet parties (especially the

British Labourites and the French Socialists)

are acting as agents of the United States

imperialist circles, there has developed

upon the Communists the special historic

task of leading the resistance to the

American plan for the enthrallment of

Europe, and of boldly denouncing all

coadjutors of American imperialism in their

own countries. At the same time,

Communists must support all the really

patriotic elements who do not want their

countries to be imposed upon, who want to

resist enthrallment of their countries to

foreign capital, and to uphold their national

sovereignty.”

“A. Zhdanov at the Founding of the Cominform,

September 1947”, Documents on International

Affairs 1947-1948, pp. 122-37.

In Hanhimäki and Westad, The Cold War, 50-52](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-55-320.jpg)

![“In his 20 January speech Truman declared that a draft North

Atlantic Pact will soon be put before the Senate, the official

aims of which are stated to be a desire to strengthen

security in the North Atlantic. […] Just as the

implementation of the Marshall Plan is directed not at the

genuine economic regeneration of European states, but is a

means of adapting the politics and economics of the

‘Marshallized’ countries to the selfish military and strategic

plans of Anglo-American domination in Europe, in the same

way the formation of a new grouping is not at all for the

mutual assistance and collective security of the Western

Union, in so far as by the Yalta and Potsdam Agreements

these countries are not threatened with any aggression. Its

aim is to strengthen and considerably extend the dominant

influence of Anglo-American ruling circles in Europe, and to

subordinate all the domestic and foreign policies of the

corresponding European states to their own narrow

interests...

…the instigators of the North Atlantic Pact have from the

outset precluded any possibility of participation by the

People’s Democracies and the Soviet Union in that pact,

making it clear that not only could these states not be

participants, but that the North Atlantic Pact is directed

precisely against the USSR and the new democracies […].”

The Soviet reaction to

NATO

The Soviet government

reacted to the new

organisation by denouncing it

as a veiled attempt to impose

Anglo-American domination

over Europe and threaten the

Eastern bloc. In this

declaration, issued by the

Soviet Foreign Ministry, the

USSR claimed that NATO could

not have a defensive purpose

because there was no

Communist threat against the

West. Explicitly comparing it to

the Marshall Plan, the Soviet

government claimed instead

that it was aimed against the

People’s Democracies.

Declaration of the Soviet Foreign

Ministry on the North Atlantic Pact,

Izvestiya, 29 January 1949.

Source: Edward Acton and Tom

Stableford (eds.), The Soviet Union: A

Documentary History Vol. 2, 212-13.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-60-320.jpg)

![The Berlin Airlift

In accord with the four Power Agreement of 4 May, 1949 the USSR lifted the blockade on 12

May. It was once more possible to travel by road from Berlin to Hannover, which the persons

depicted in this photograph are celebrating. The sign on the car reads: ‘Hurra wir leben

noch’, ]‘Hurray, we are still alive’].

‘Hurray, we are still alive!’

Imperial War Museum,

IWM (BER 49-164-009)

IWM Non Commercial Licence](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-65-320.jpg)

![Creation of the Federal Republic of

Germany (FRG) and the German

Democratic Republic (DDR)

On 23 May 1949, the trizone of the British,

French and American sectors established the

Federal Republic of Germany. This was

perceived in Moscow as a provocation as well

as a rejection by the Western powers of what

had been agreed between the wartime Allies

at Yalta and Potsdam.

It was followed by a decision to create the

German Democratic Republic in Soviet-

occupied East Germany on 7 October 1949.

Wilhelm Pieck, the first President of the

German Democratic Republic [East

Germany] reading out the new

Constitution in Berlin on 7 October, 1949

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-S88612 / CC-BY-SA

3.0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-68-320.jpg)

![Western powers provide aid to

communist Yugoslavia after the split with

the Soviet Union

Between 1945 and 1948 Washington saw

Marshal Josip Tito, Prime Minister of

Yugoslavia and General Secretary of the

Yugoslav Communist Party as a tool of the

Kremlin. But Tito’s support for the

Communists in the Greek Civil War, against

the express wishes of Stalin, led to Yugoslavia

being expelled from COMINFORM and a

permanent split emerged between Stalin and

Tito. The Truman administration saw the

offer of aid to Yugoslavia as a means of

driving an even deeper wedge between the

two. The decision was remarkable in that it

was still financial aid to a communist country

and to a leader who was often at odds with

Washington just as he was at odds with

Moscow.

The Washington Post

Yugoslavia to Get Aid From Western

Nations

By Dan Morgan,

September 18, 1951

[Western diplomats] “say the economic

health of Yugoslavia is a key factor in the

country's independence from Soviet

influence….. Engaged in the assistance

effort along with the United States are

West Germany, Italy, Britain,

Switzerland, France and the

International Monetary Fund. Others in

the "club" of rich industrial countries,

such as Japan, and the Netherlands, may

also be asked to help, diplomatic sources

report.

The immediate thrust of the aid is to

stabilize the economy, now showing many

of the erratic, inflationary trends of

rapid development, and to improve the

country's worsening balance of payments

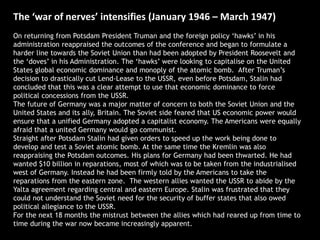

deficit…”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/coldwartensionsincrease-1945-1952-240319074246-d1fdfb02/85/Cold-War-Tensions-Increase-1945-1952-pptx-75-320.jpg)