This document discusses client-side JavaScript packages and module systems. It begins by describing CommonJS and AMD module systems, noting problems with AMD including configuration complexity and inability to easily consume third-party code. It then introduces the concept of packages as a better unit of code reuse than modules alone. NPM is presented as a package manager that solves problems of downloading, installing dependencies, and accessing other packages' code. Key aspects of NPM packages like directory structure and package.json are outlined. The document concludes by briefly covering NPM features like dependency hierarchies, Git dependencies, and using NPM without publishing to the public registry.

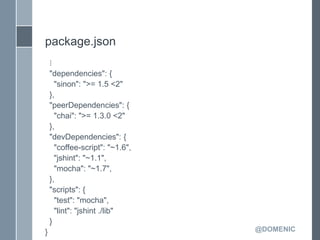

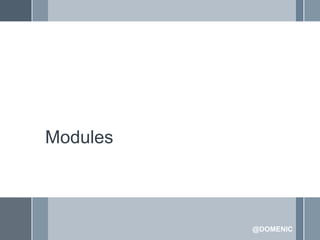

![CommonJS modules

› AMD:

define(['a', './b'], function (a, b) {

return { c: 'd' };

});

› CommonJS:

var a = require('a');

var b = require('./b');

module.exports = { c: 'd' };

@DOMENIC](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/client-sidepackages-130403024849-phpapp02/85/Client-Side-Packages-5-320.jpg)

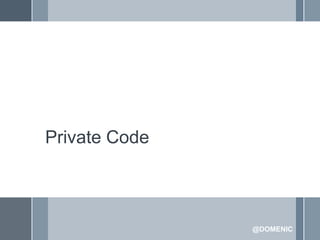

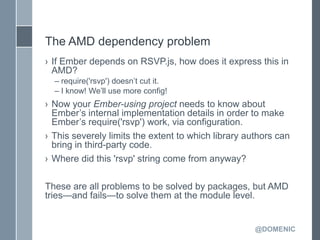

![package.json

{

"name": "sinon-chai",

"description": "Extends Chai with assertions for Sinon.JS.",

"keywords": ["sinon", "chai", "testing", "spies", "stubs", "mocks"],

"version": "2.3.1",

"author": "Domenic Denicola <domenic@domenicdenicola.com>",

"license": "WTFPL",

"repository": {

"type": "git",

"url": "git://github.com/domenic/sinon-chai.git"

},

"main": "./lib/sinon-chai.js",

⋮

@DOMENIC](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/client-sidepackages-130403024849-phpapp02/85/Client-Side-Packages-18-320.jpg)