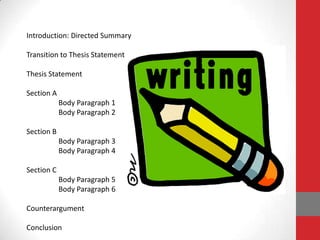

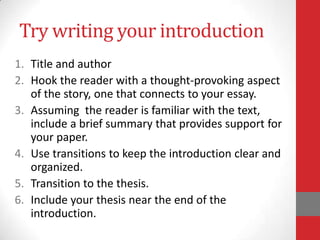

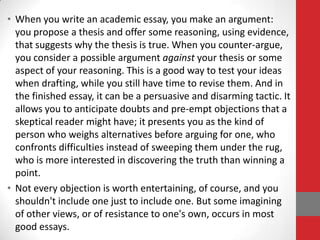

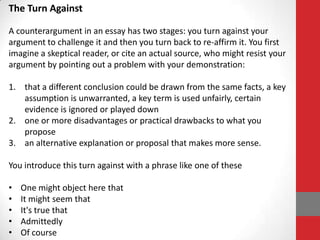

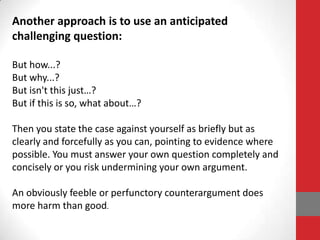

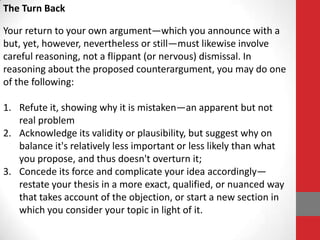

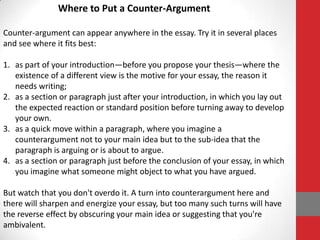

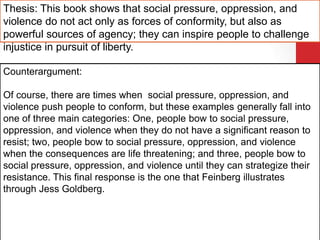

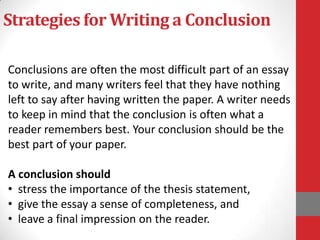

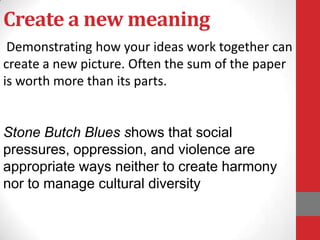

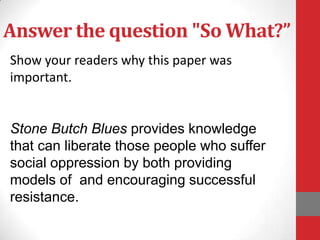

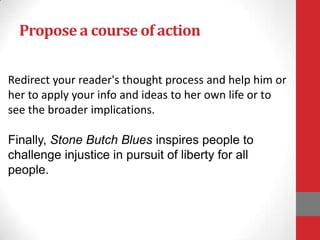

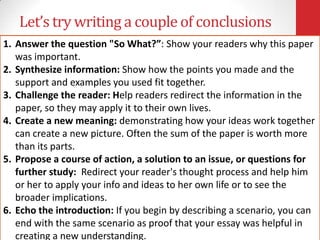

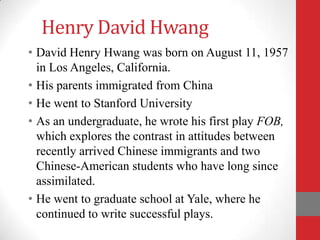

The document outlines the agenda and materials for Class 13 of the EWRT 1B course. The agenda includes a presentation on terms, a discussion of Essay #3, an in-class writing assignment on Essay #3 involving a directed summary, counterargument, and conclusion, and an author lecture. The terms list defines terms related to gender and sexuality. Guidance is provided on writing a directed summary, counterargument, and conclusion for Essay #3.

![Cultural Humility: A lifelong commitment to self-

evaluation and critique, to redressing the power imbalances

in the [interpersonal relationship] dynamic[s], and to

developing mutually beneficial and non-paternalistic

partnerships with communities on behalf of individuals and

defined populations.

FtM (F2M)/MtF (M2F): Generally, abbreviations used to

refer to specific members of the trans community. FtM

stands for female-to-male, as in moving from a female pole

of the spectrum to the male. MtF stands for male-to-female

and refers to moving from the male pole of the spectrum tot

eh female. FtM is sometimes, not always, synonymous with

transman. Conversely, someone who identifies as MtF, may

identify as a transwoman.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/class131b-120520193202-phpapp01/85/Class-13-1-b-6-320.jpg)