This document provides an overview of China's business environment, including:

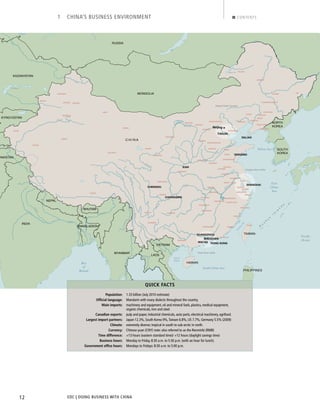

1. China has experienced rapid economic growth averaging 10% annually since 1993, transforming it into a global economic powerhouse. It is now the world's largest exporter and second largest economy.

2. The government is focusing on moving up the value chain in manufacturing, cultivating high-tech industries, and building an internal consumer market to reduce dependence on exports.

3. Demographic changes include a growing middle class estimated at 600-700 million by 2020, and an aging population that will impose demands on the state to ensure stability.

4. China remains an attractive destination for foreign direct investment, receiving around $90 billion in 2009,