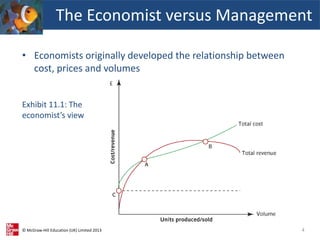

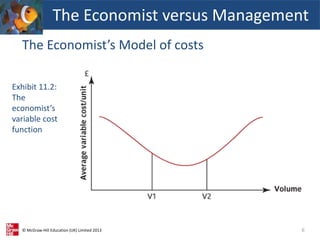

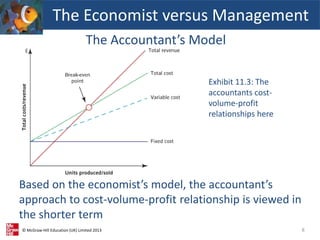

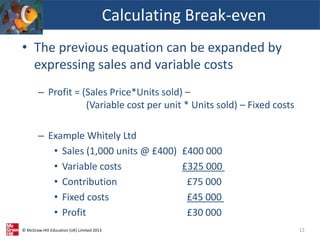

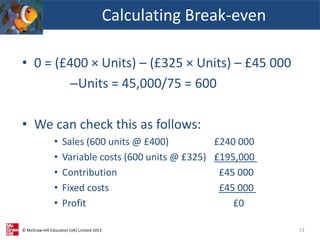

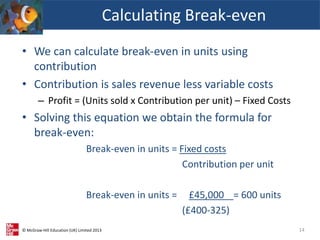

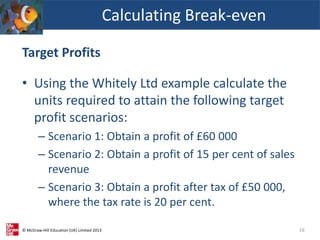

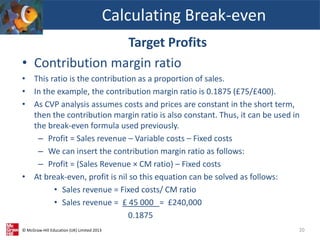

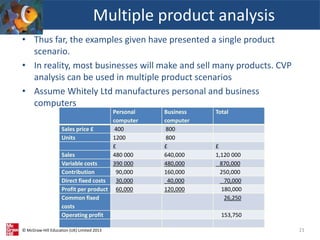

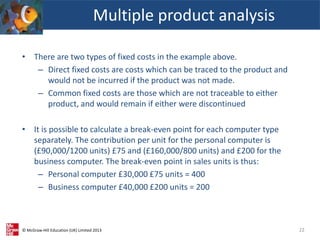

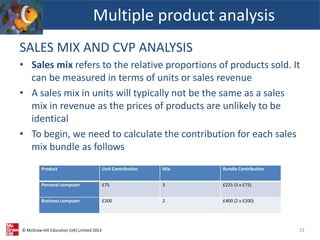

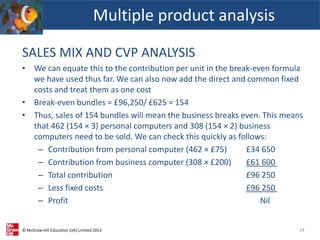

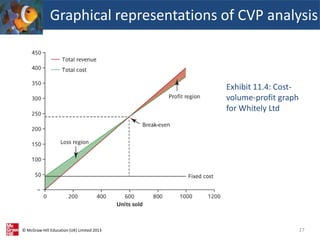

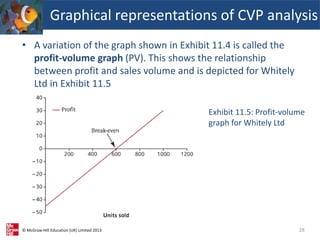

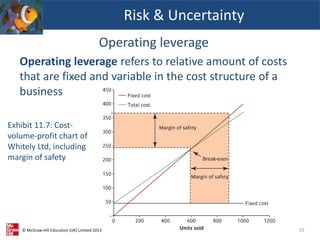

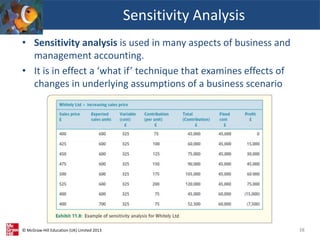

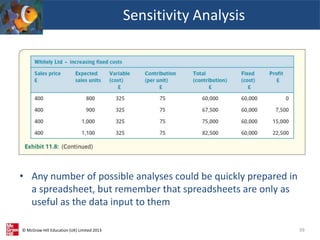

This document provides an overview of cost-volume-profit (CVP) analysis. It discusses how CVP analysis relates costs and revenues to production volumes. It explains the economist and accountant perspectives on CVP and how the accountant's model is more relevant for short-term decision making. The document also demonstrates how to calculate break-even points, the sales required to achieve profit targets, and how CVP analysis can be applied to businesses that produce multiple products.