The document introduces psychopharmacology, emphasizing its complexity and the necessity for mental health professionals to integrate knowledge of brain science, pharmacodynamics, and cultural factors in understanding psychotropic medications. It encourages readers to embrace the complexities of the mind and brain while learning about the advances in neuroscience that have influenced drug development. The authors advocate for a comprehensive approach to psychopharmacology that goes beyond mere medical models, incorporating diverse perspectives to enhance clinical practice.

![many of these drugs is modest at best. [For example, meta-

analyses suggest antidepressants are only better than placebo

50% of the time (Khan, Leventahl, Khan, & Brown, 2002).]

Another problem has been a steep increase in the number of

lawsuits and amounts in settlements where companies were

fined for questionable practices linked to psychotropic

medications. In 2012 alone, companies paid over $5 billion in

fines related to allegations of fraud including misleading claims

about drug safety (Associated Press, 2009; Isaacs, 2013). That

said, it remains to be seen how much new research will be done

on pharmacological interventions because we know that mental

and emotional disorders are more complex than brain chemistry.

Certainly current medications that target receptors sites will be

used for symptom control so understanding binding is still

important. Until we can understand the etiology of mental

disorders, symptom control may be the best we can do.

Although we know from Chapter Two that drugs bind to

receptors to cause main effects, it is important to note that

drugs may also bind at sites where there appear to be no

measurable effects. These sites are called drug depots and they

include plasma protein, fat and muscle. Depot binding does

effect drug action in that it decreases the concentration of the

drug at sites of action because only freely circulating drugs can

pass across membranes. Also because these molecules will

eventually unbind and re-enter bloodstream it can lead to

higherthan-expected plasma levels and in some cases drug

overdose (Meyer & Quenzer, 2005).

Types of Tolerance

It is important to generally understand the types of tolerance

clients can develop to drugs. Please note that in this book we

avoid using the word “addiction.” The emotional hysteria

around this word, and the lack of operational definitions, make

it too inexact to be helpful. Physical dependence is linked with

the term addiction and implies that withdrawal signs are “bad”

and only linked to drugs of abuse. This is far from the truth

because severe withdrawal signs can follow cessation of such](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapteroneintroductionlearningobjectivesbeabletoconcept-221119173534-5fdf2160/85/CHAPTER-ONEIntroductionLearning-Objectives-Be-able-to-concept-docx-82-320.jpg)

![ITIS

Presentation Hints

Use dot points

Forces you not to read the slide, but to paraphrase

Describe using diagrams if that is easier

Raise and Lower the pitch of your voice

Make it more interesting to listen to

Time it correctly (ie practice it)

With Powerpoint, you can replace the voice on each slide

separately, if you mess up

Suggestion to vastly reduce MP4 file size

Use ffmpeg as follows

> ffmpeg -i %infile% -c:v libx264 -crf 50 -b 24k -ac

%outfile%.mp4

RMIT University, COSC2737 IT Infrastructure & Security

Assignment 1: Presentation Overview

11

ITIS

Interplanetary File System

Jill A Student, [email protected]

Presented as part of Assignment 1 for

COSC2737 IT Infrastructure and Security

Semester 1, 2020](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapteroneintroductionlearningobjectivesbeabletoconcept-221119173534-5fdf2160/85/CHAPTER-ONEIntroductionLearning-Objectives-Be-able-to-concept-docx-94-320.jpg)

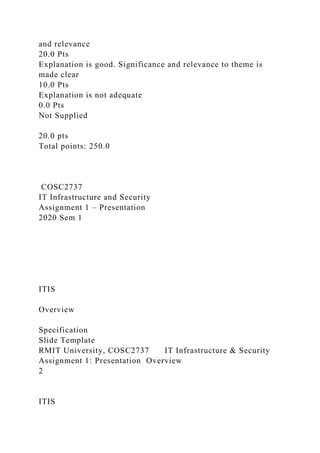

![Jill A Student, [email protected]

Presented as part of Assignment 1 for

COSC2737 IT Infrastructure and Security

Semester 1, 2020

ITIS

Overview

The problem of reliable insterplanetary communication where

transmission latency is significant

Classic Paper: Reliable Internet from Mars

The InterPlaNetary Internet: a communications infrastructure

for Mars exploration

Making IPFS secure and trustable

BlockIPFS-Blockchain-enabled Interplanetary File System for

Forensic and Trusted Data Traceability

…and you thought your IoT didn’t have the range !!

An InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) based IoT framework

Security Hacks

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) Hacked for 10 Months

CVE-2018-0256 : A vulnerability in the peer-to-peer message

processing functionality of Cisco Packet Data Network

RMIT University, COSC2737 IT Infrastructure & Security

Assignment 1: Presentation Overview](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapteroneintroductionlearningobjectivesbeabletoconcept-221119173534-5fdf2160/85/CHAPTER-ONEIntroductionLearning-Objectives-Be-able-to-concept-docx-112-320.jpg)