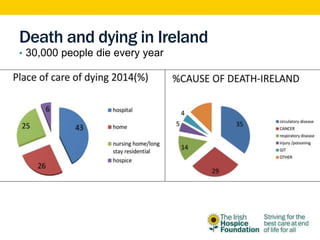

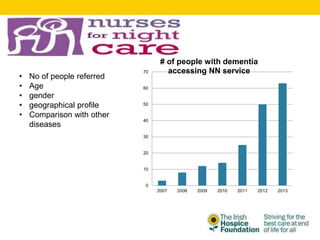

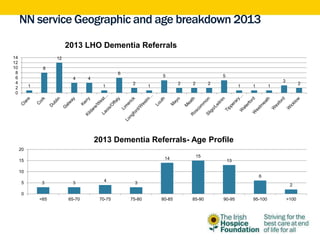

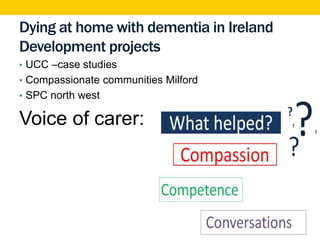

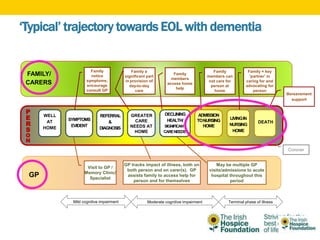

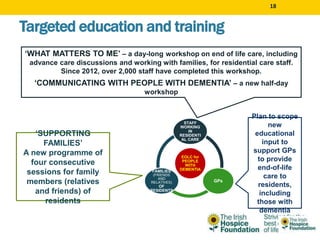

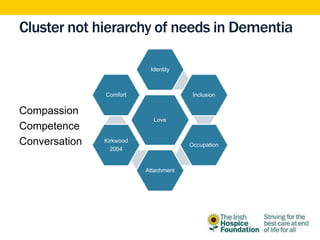

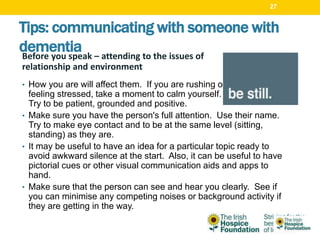

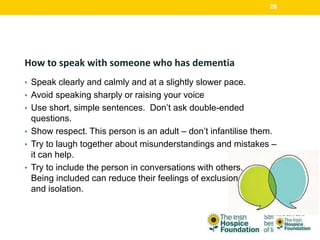

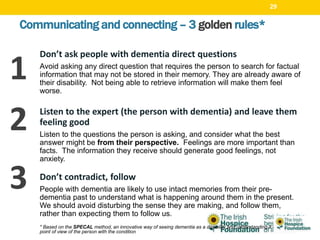

The document discusses supporting people with dementia at end of life. It outlines the Irish Hospice Foundation's (IHF) vision of ensuring dignity and comfort for all facing end of life. The IHF runs several programs, including on palliative care and bereavement. Data shows more people with dementia die in care homes than at home. The IHF nurses service data found most referrals were older adults and from certain areas. Literature suggests place of death is influenced by illness factors and care circumstances. The document outlines IHF education initiatives to improve end of life care and communication for people with dementia, their families, and staff. It stresses the importance of person-centered communication and considering the emotional needs of those with dementia.