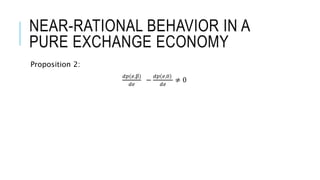

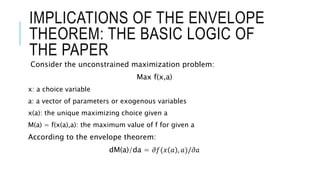

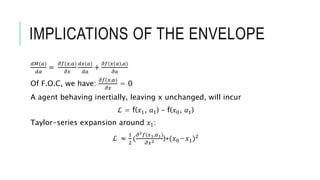

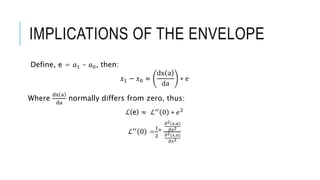

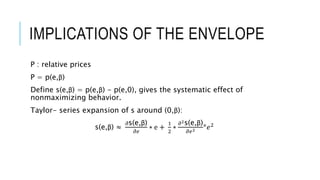

Akerlof and Yellen discuss the impact of small deviations from rational behavior on economic equilibria, highlighting how decision biases can affect market dynamics, such as the persistence of cartels and the business cycle. They explore the implications of the envelope theorem, near-rational behavior in exchange economies, and the consequences of monopolistic behavior and money supply shocks on welfare. The conclusion emphasizes the significant welfare and policy implications resulting from the identified decision biases.

![NEAR-RATIONAL BEHAVIOR IN A PURE

EXCHANGE ECONOMY

Proposition 1:

𝑑𝑈 𝑚

𝑑𝑒

=

𝑑𝑈 𝑛

𝑑𝑒

𝑑𝑉 𝑚

𝑑𝑒

=

𝑑𝑉 𝑛

𝑑𝑒

𝑈 𝑚(e,β) = u(p(e, β),𝑥1

−

+p(e, β) 𝑥2

−

(1 + 𝑒))

𝑑𝑈 𝑚

𝑑𝑒

= λ1[𝑝 𝑜 𝑥2

−

+(𝑥2

−

-𝑥2

𝑜

)

𝑑𝑝

𝑑𝑒

]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cansmalldeviationfromrationalitymakesignificantdifferencestoeconomicequilibia-160515153405/85/Can-small-deviation-from-rationality-make-significant-differences-to-economic-equilibia-8-320.jpg)