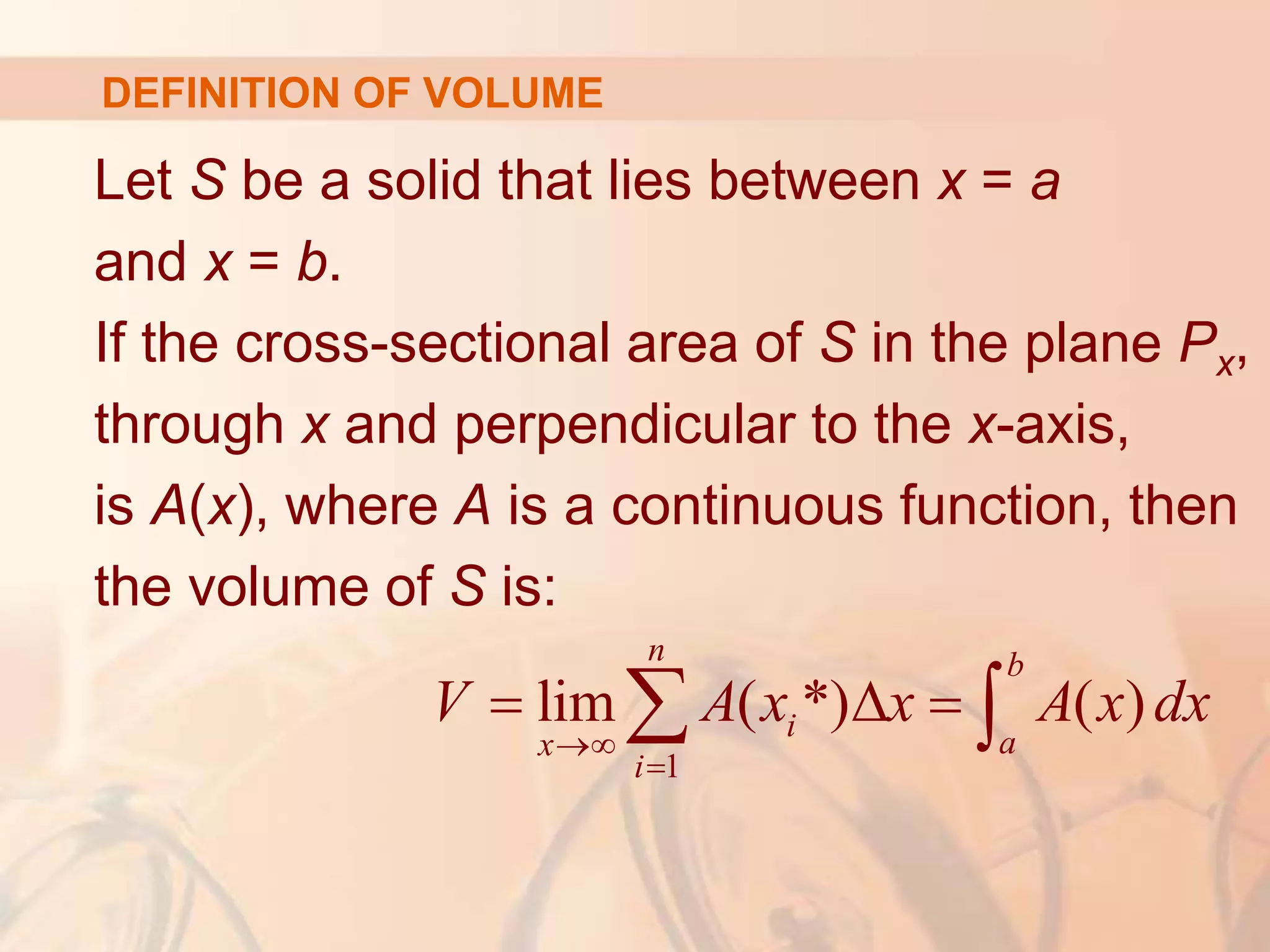

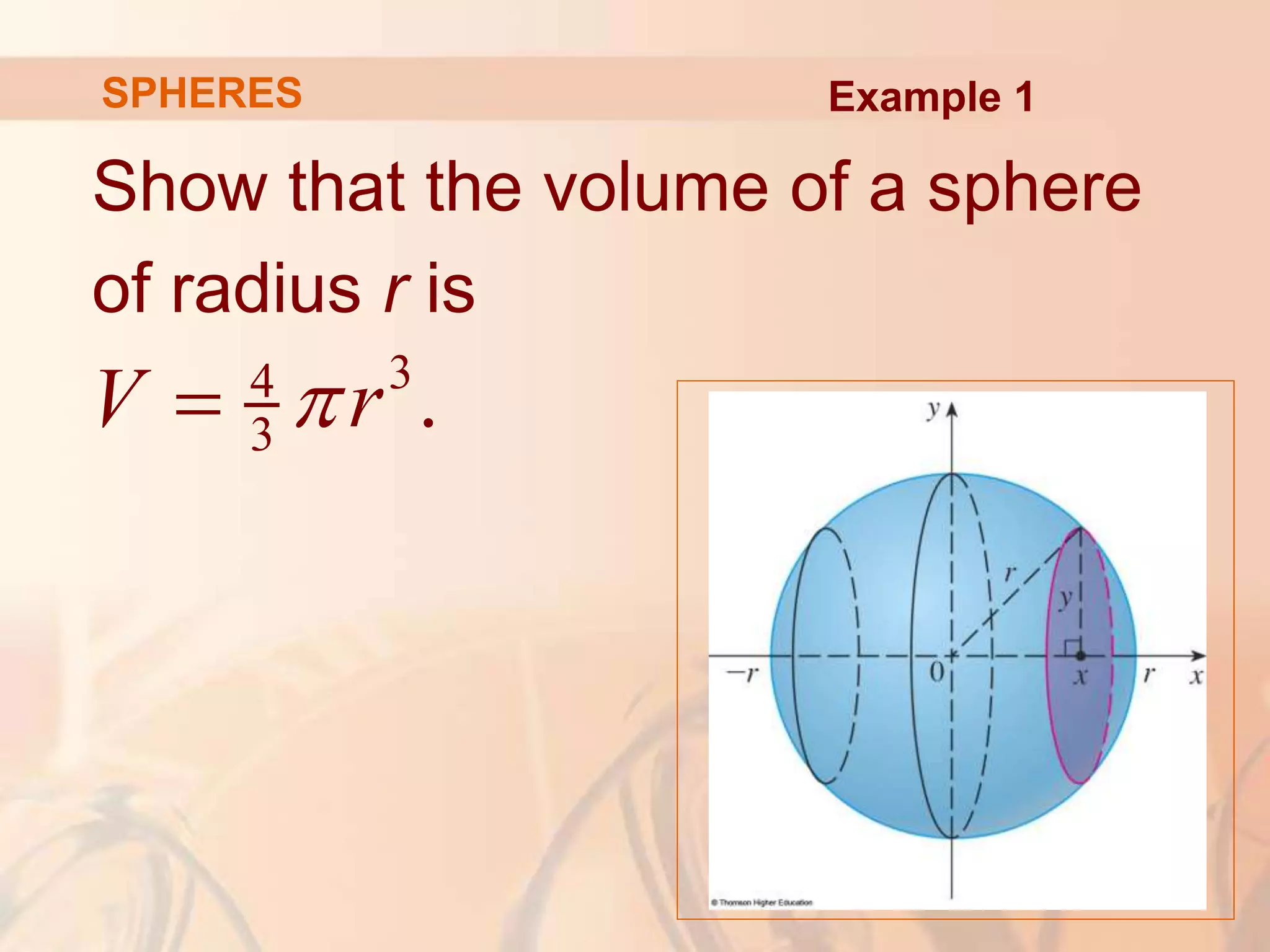

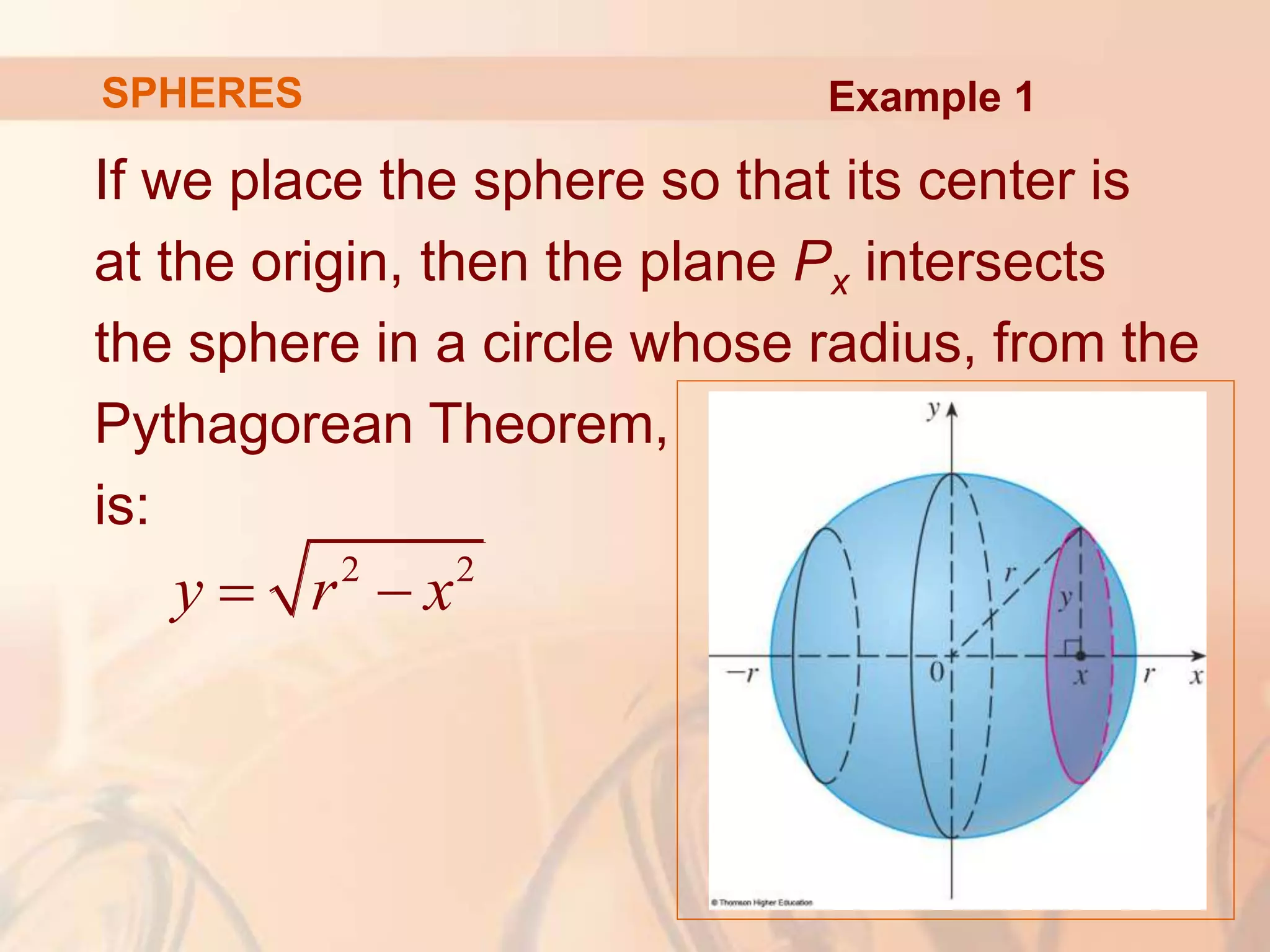

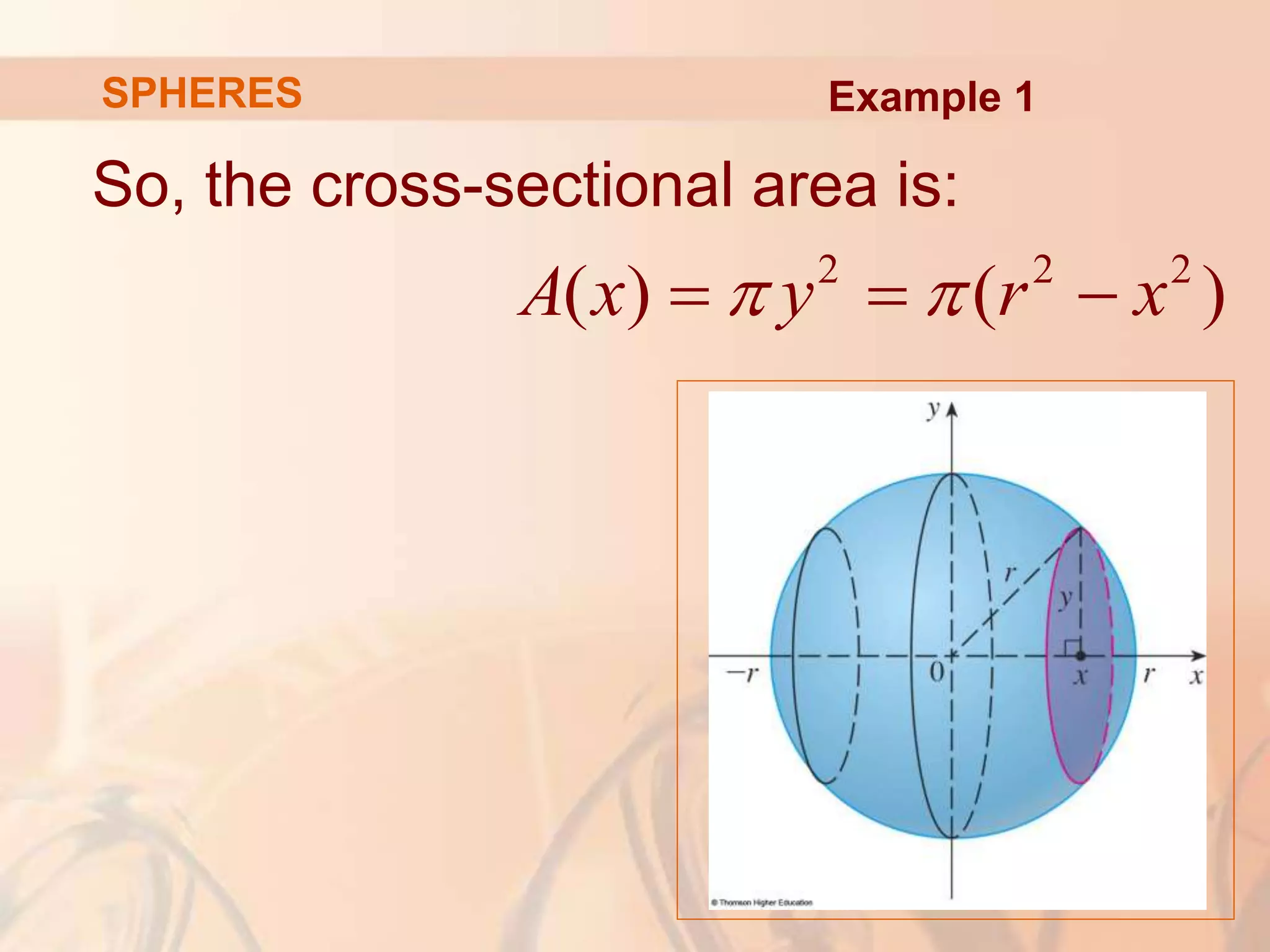

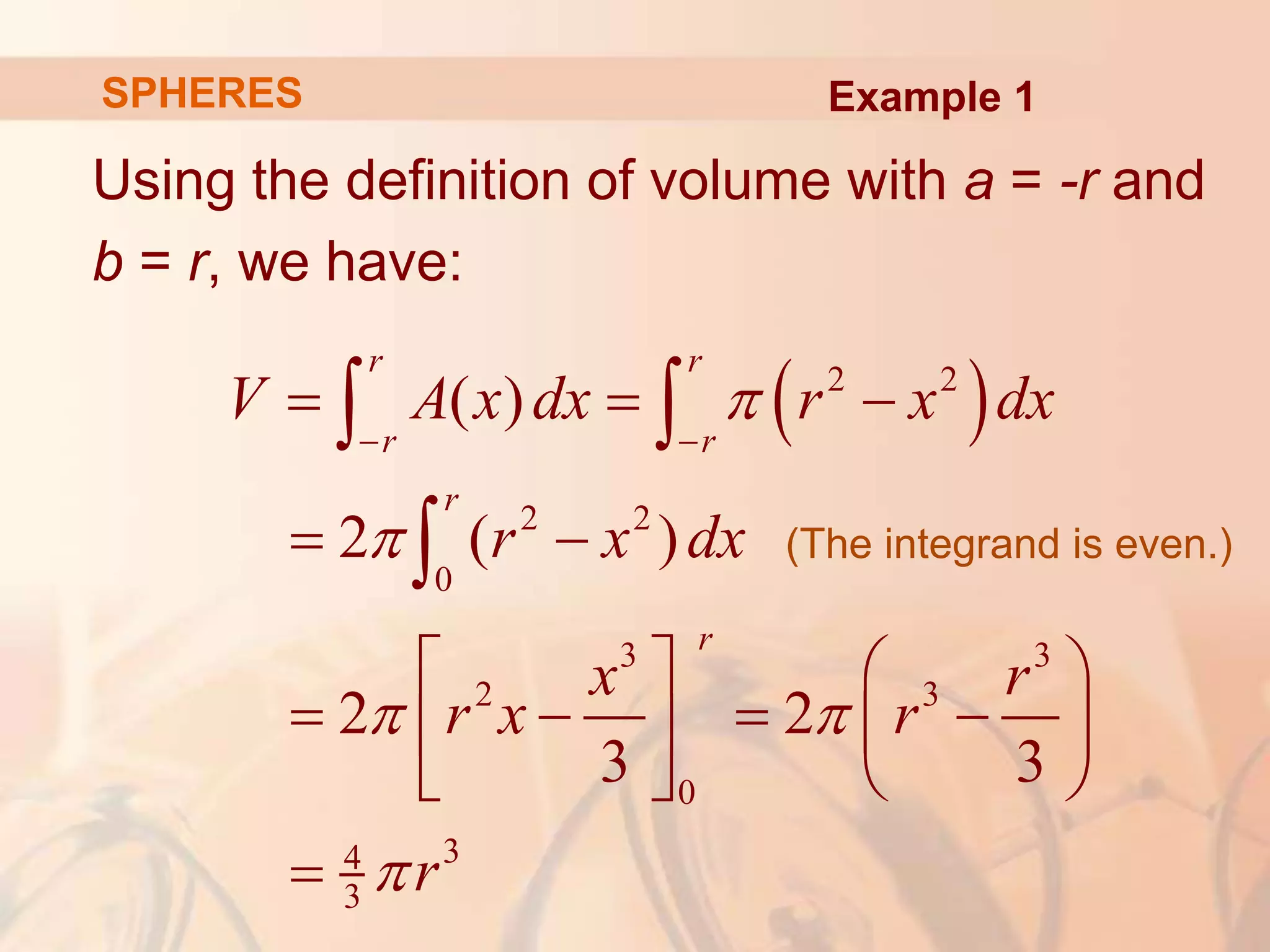

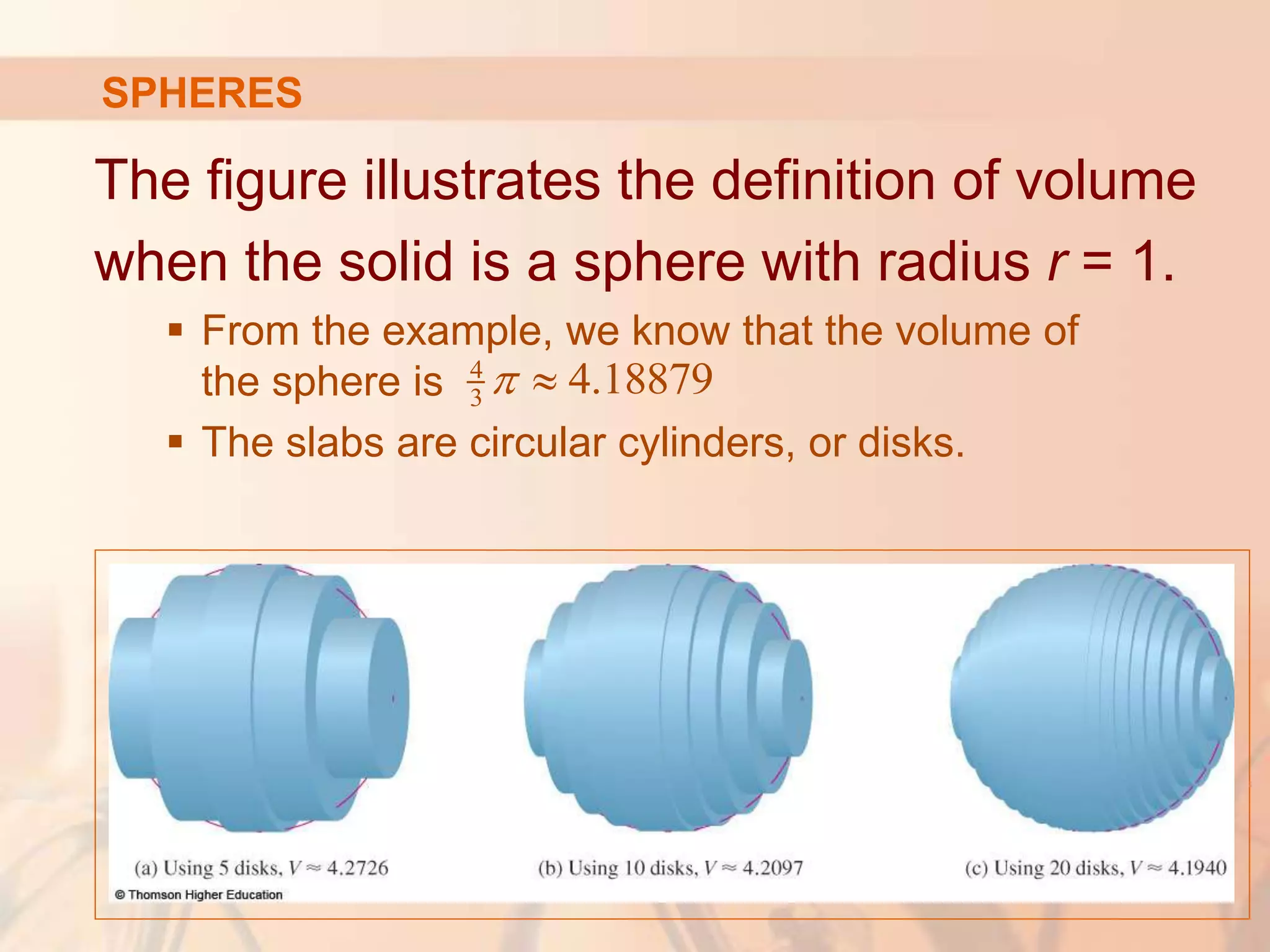

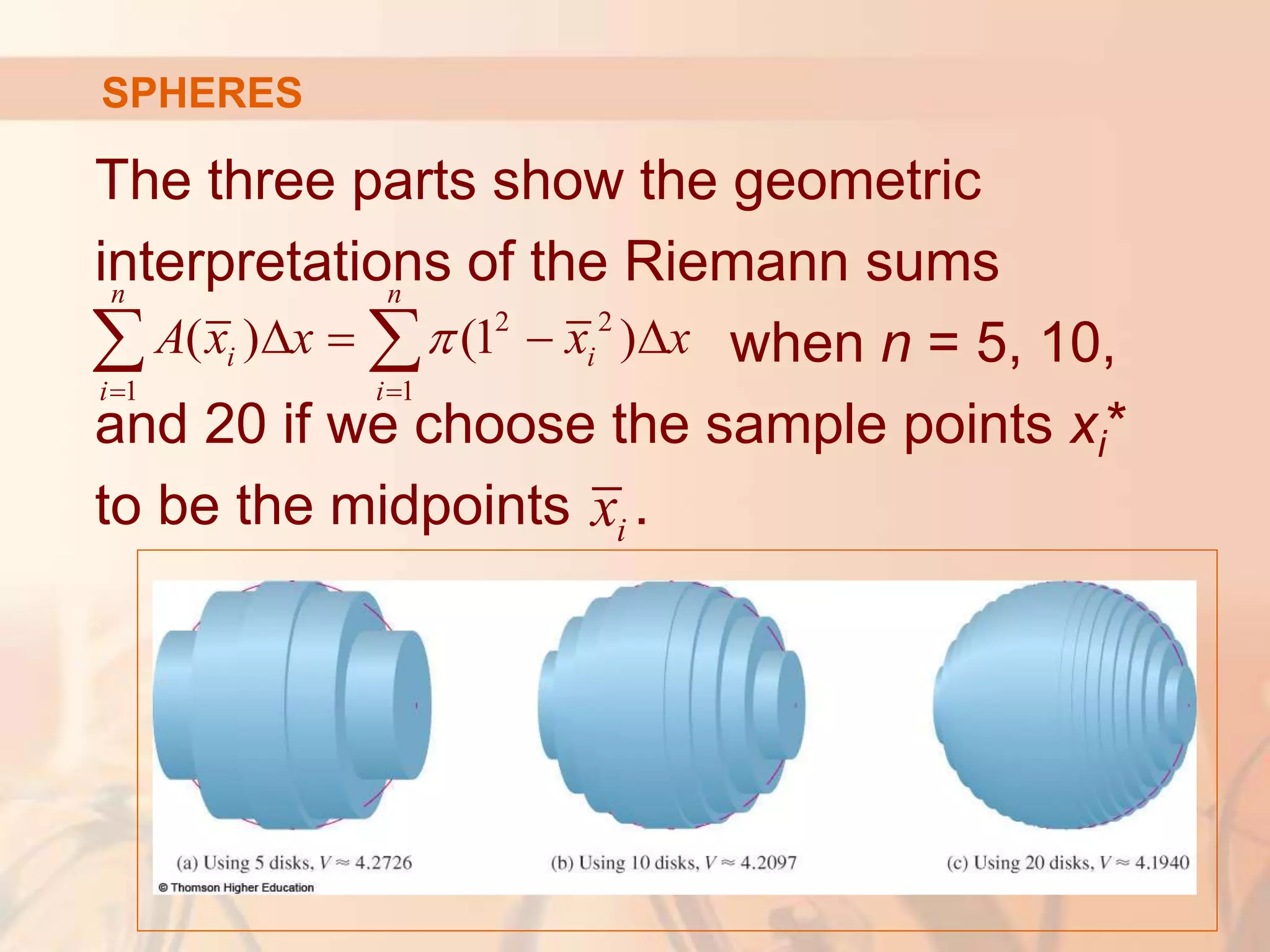

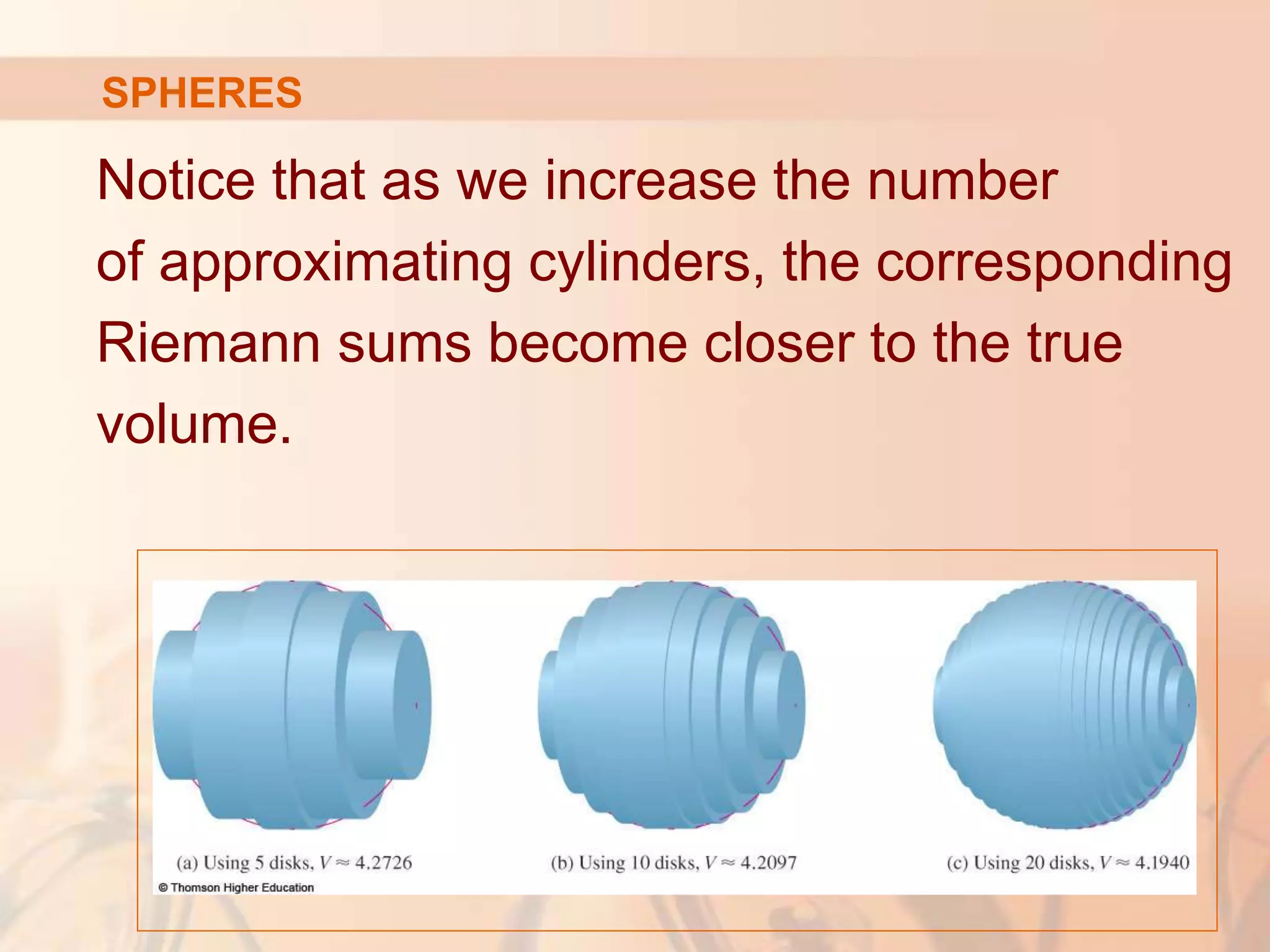

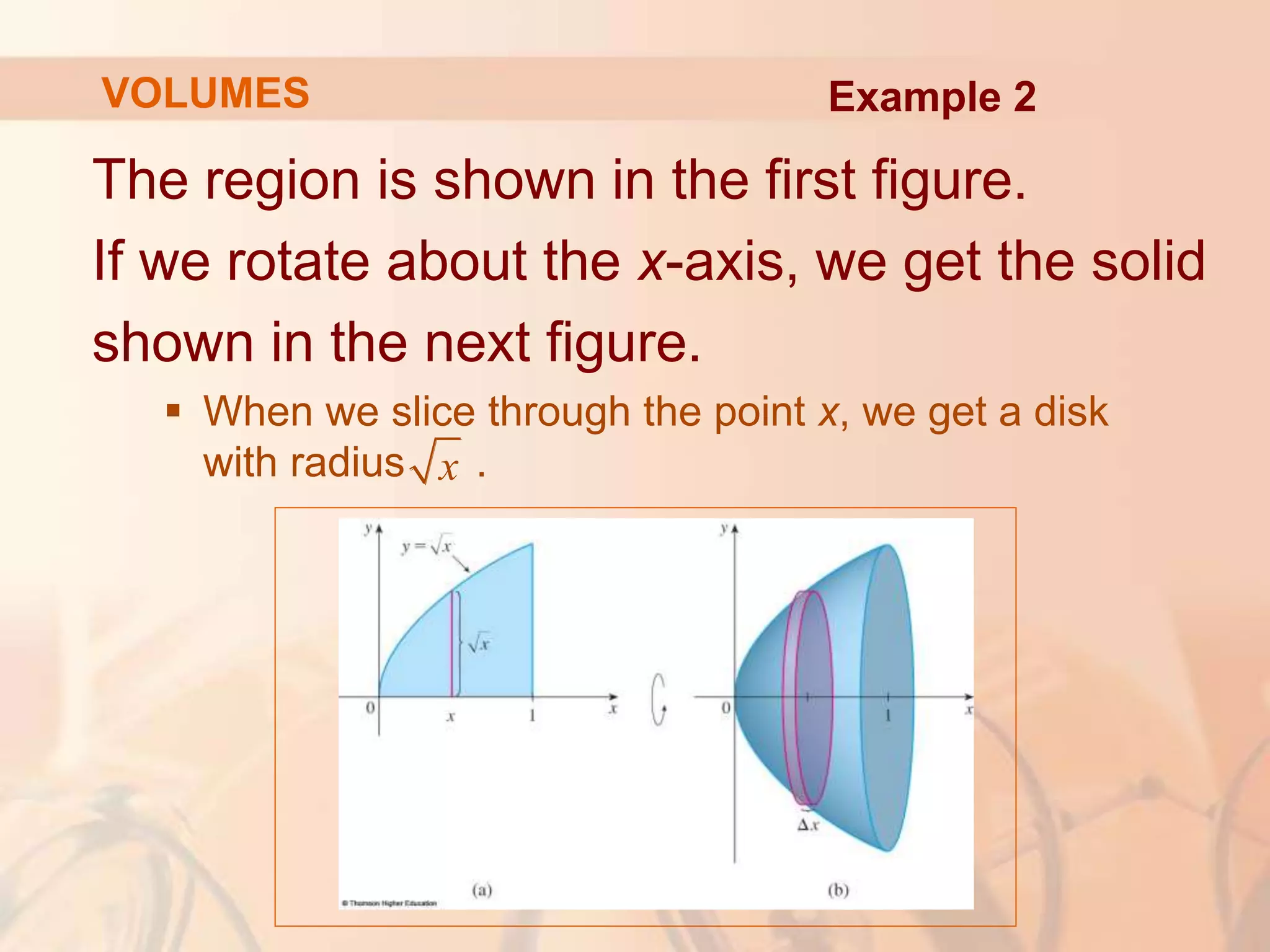

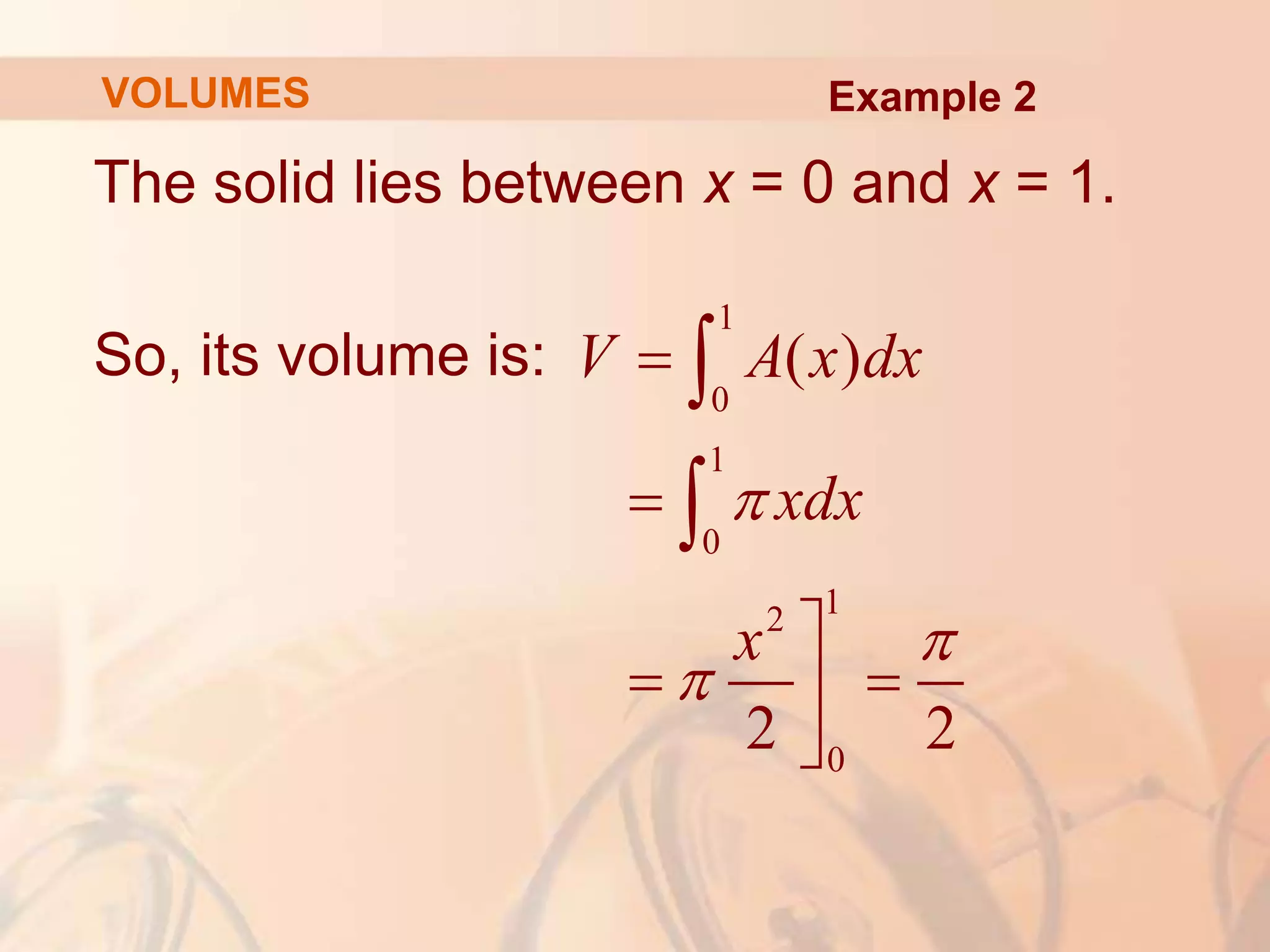

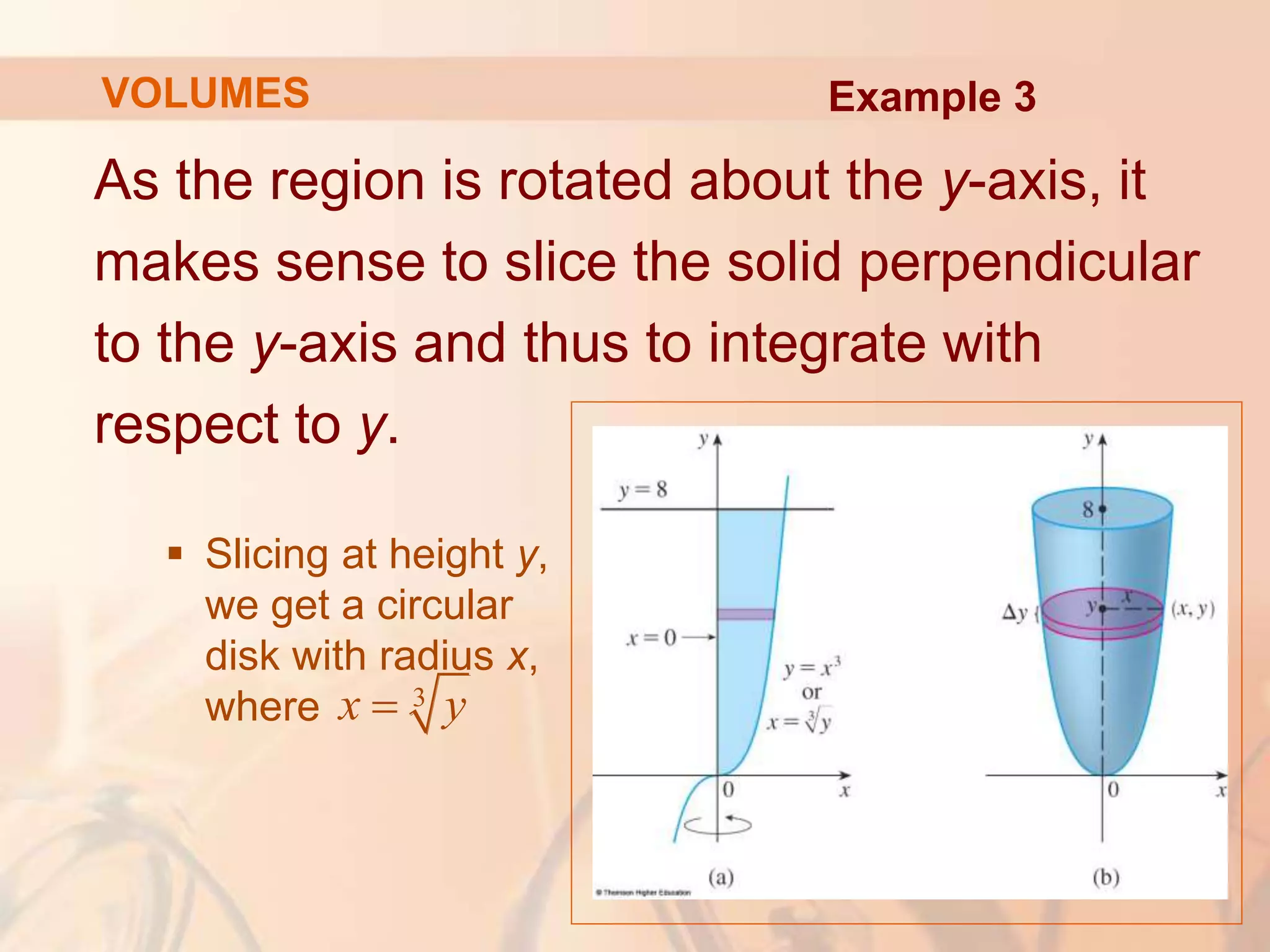

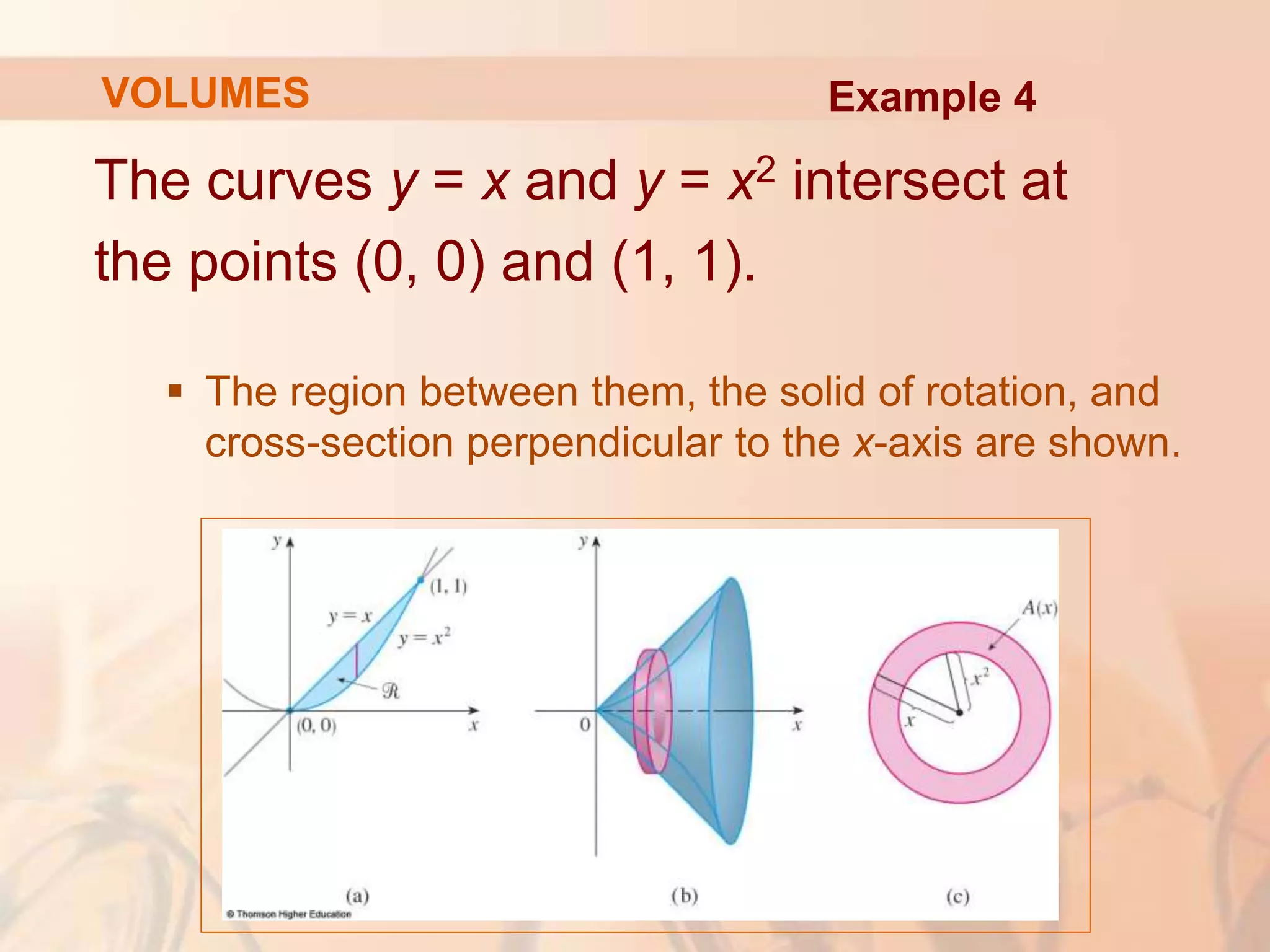

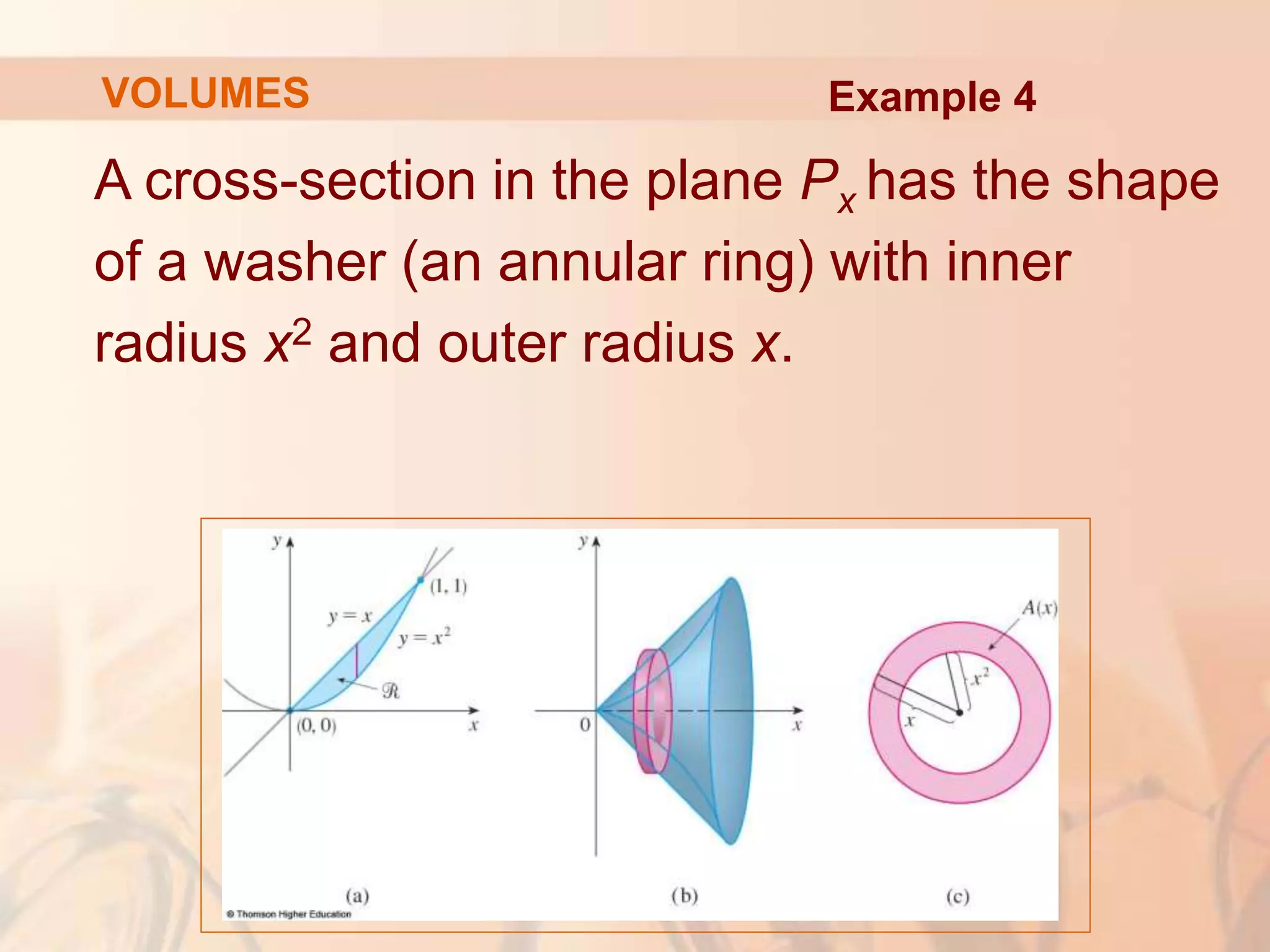

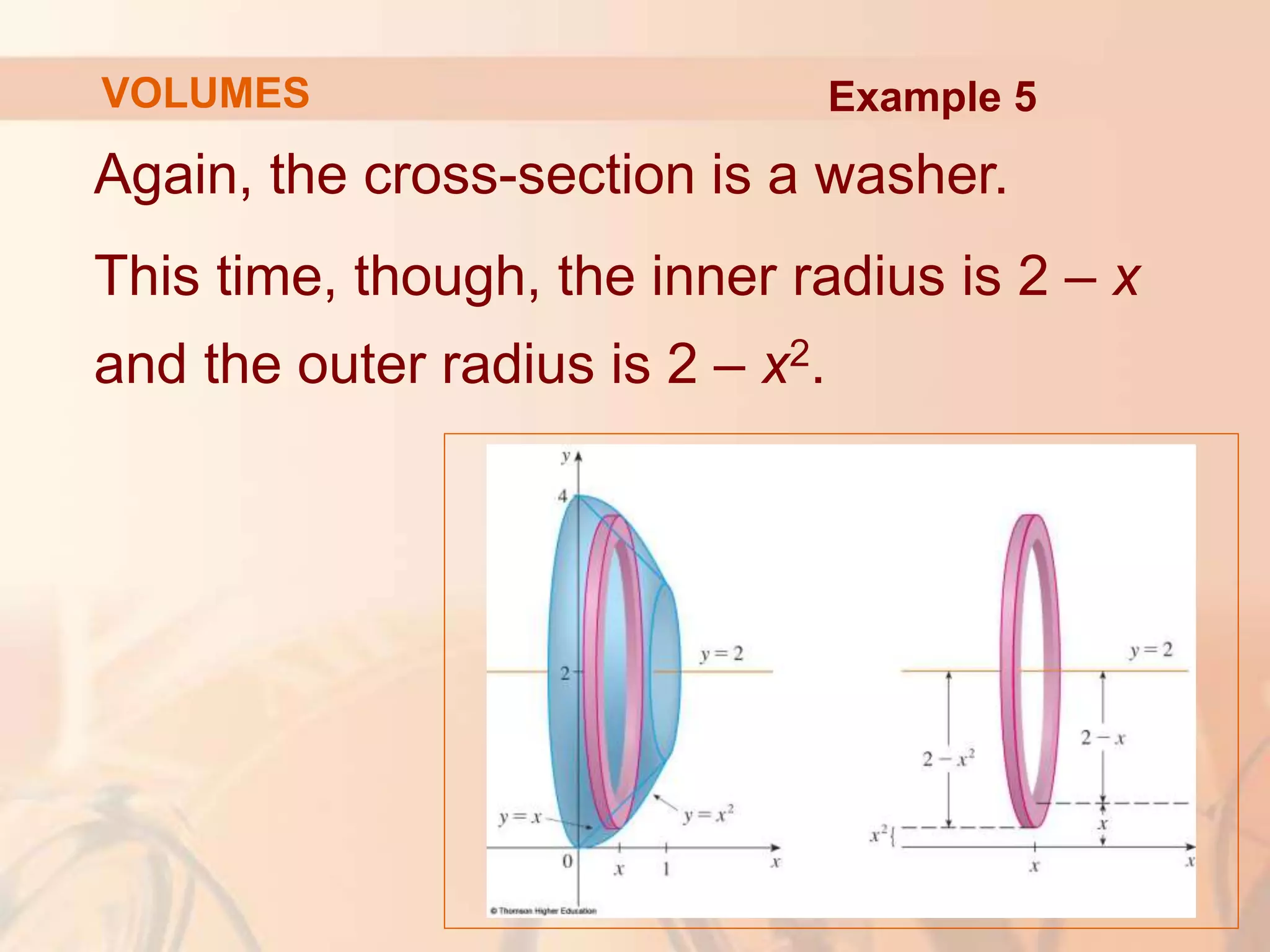

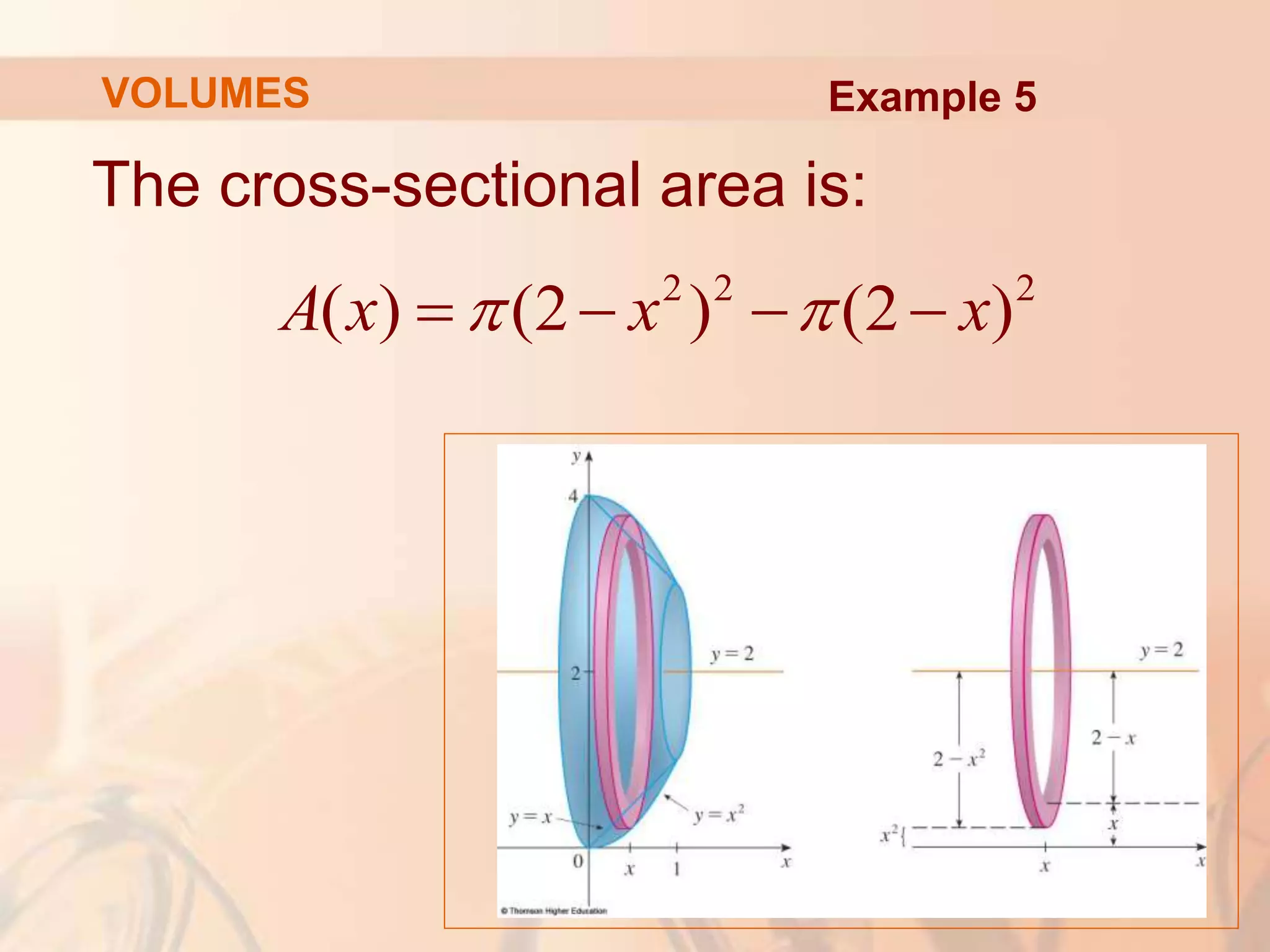

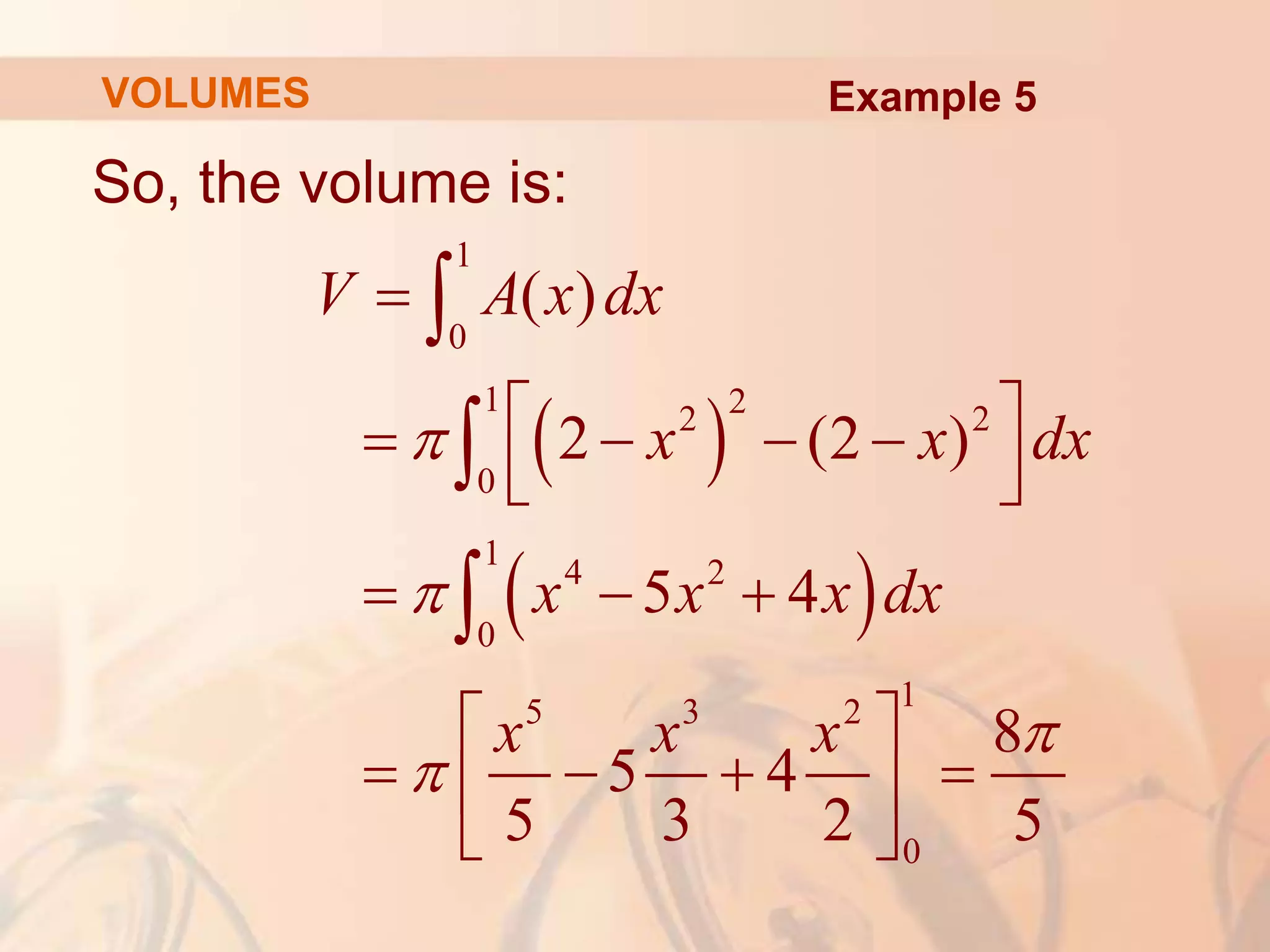

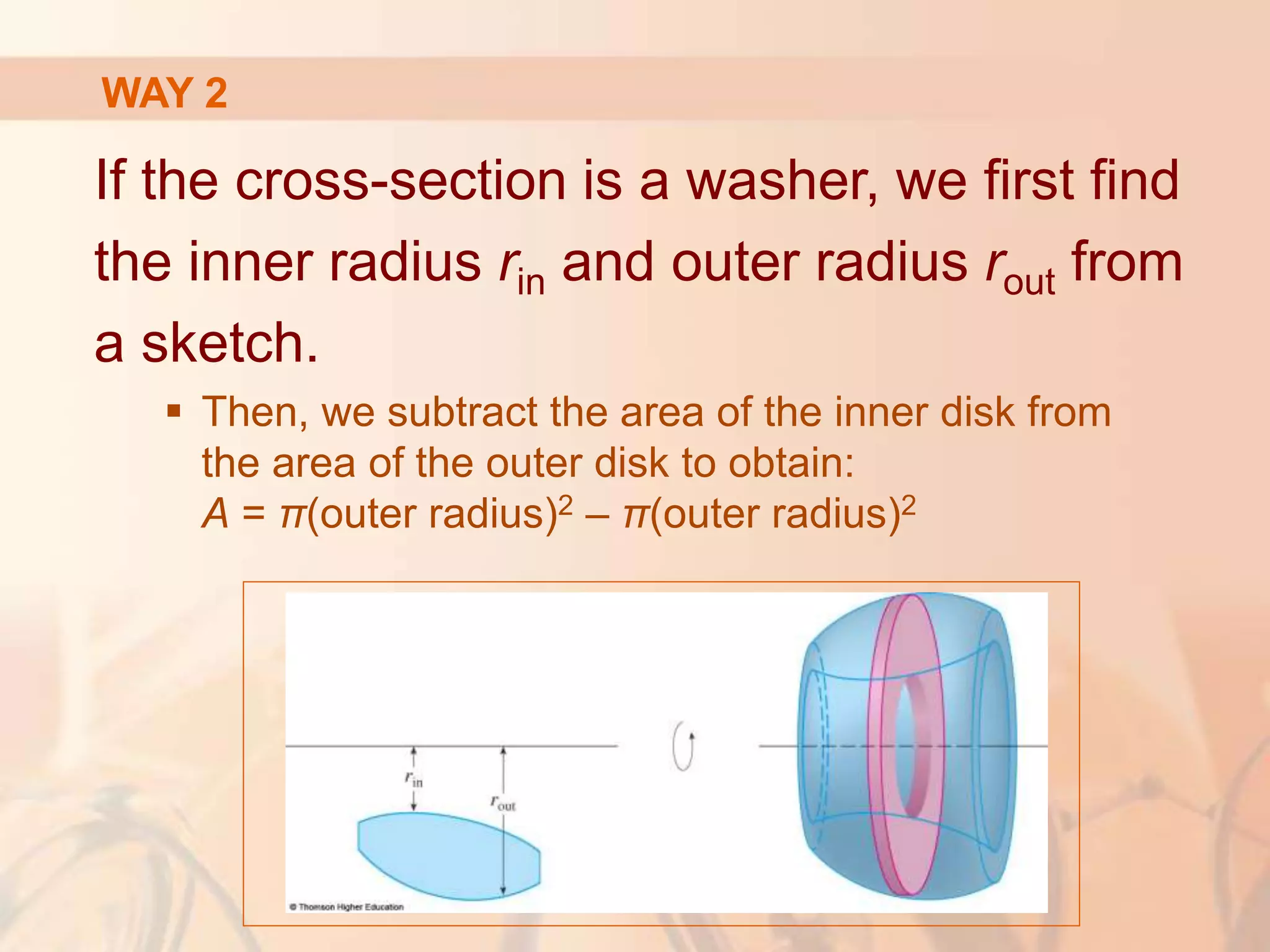

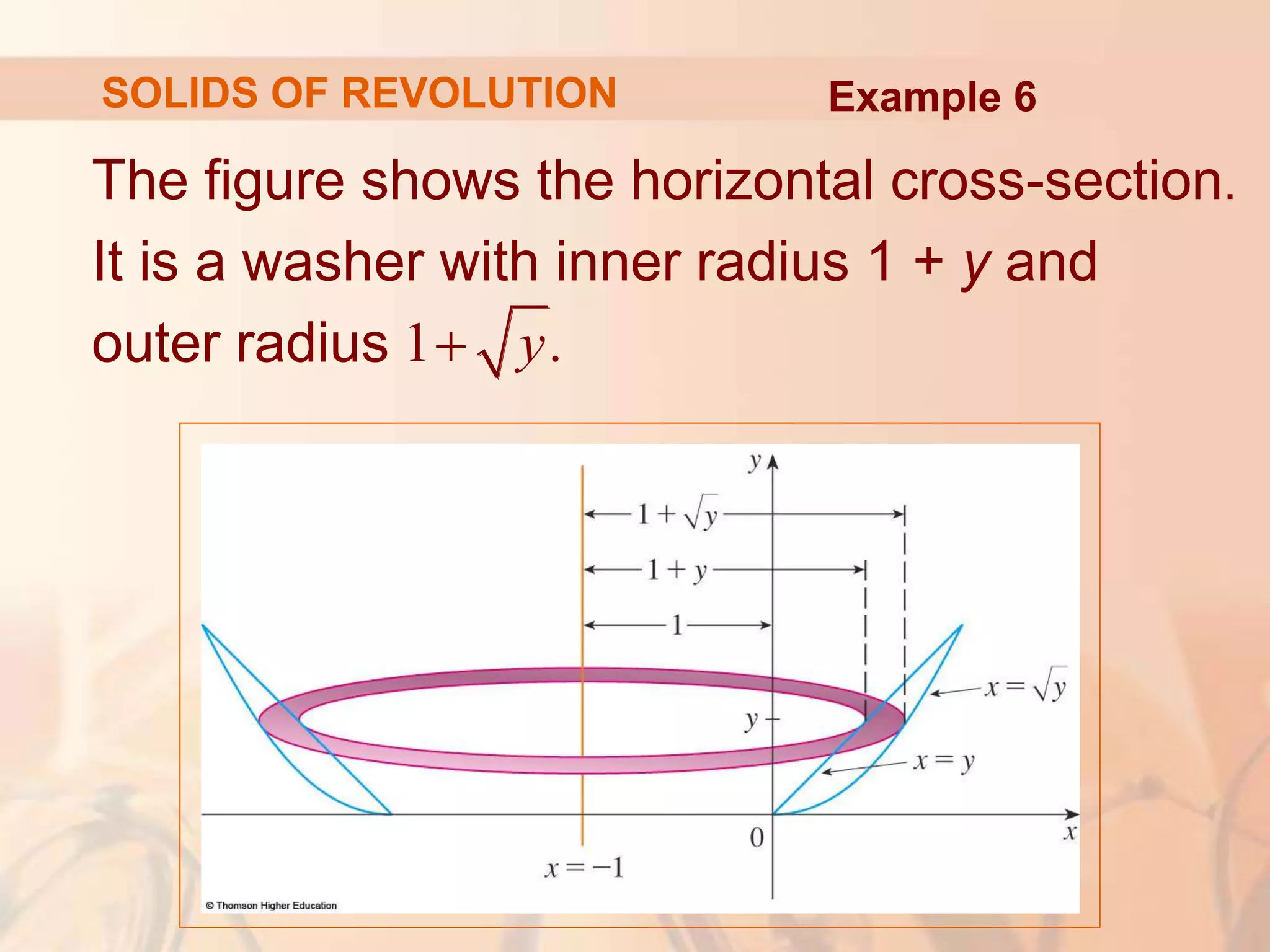

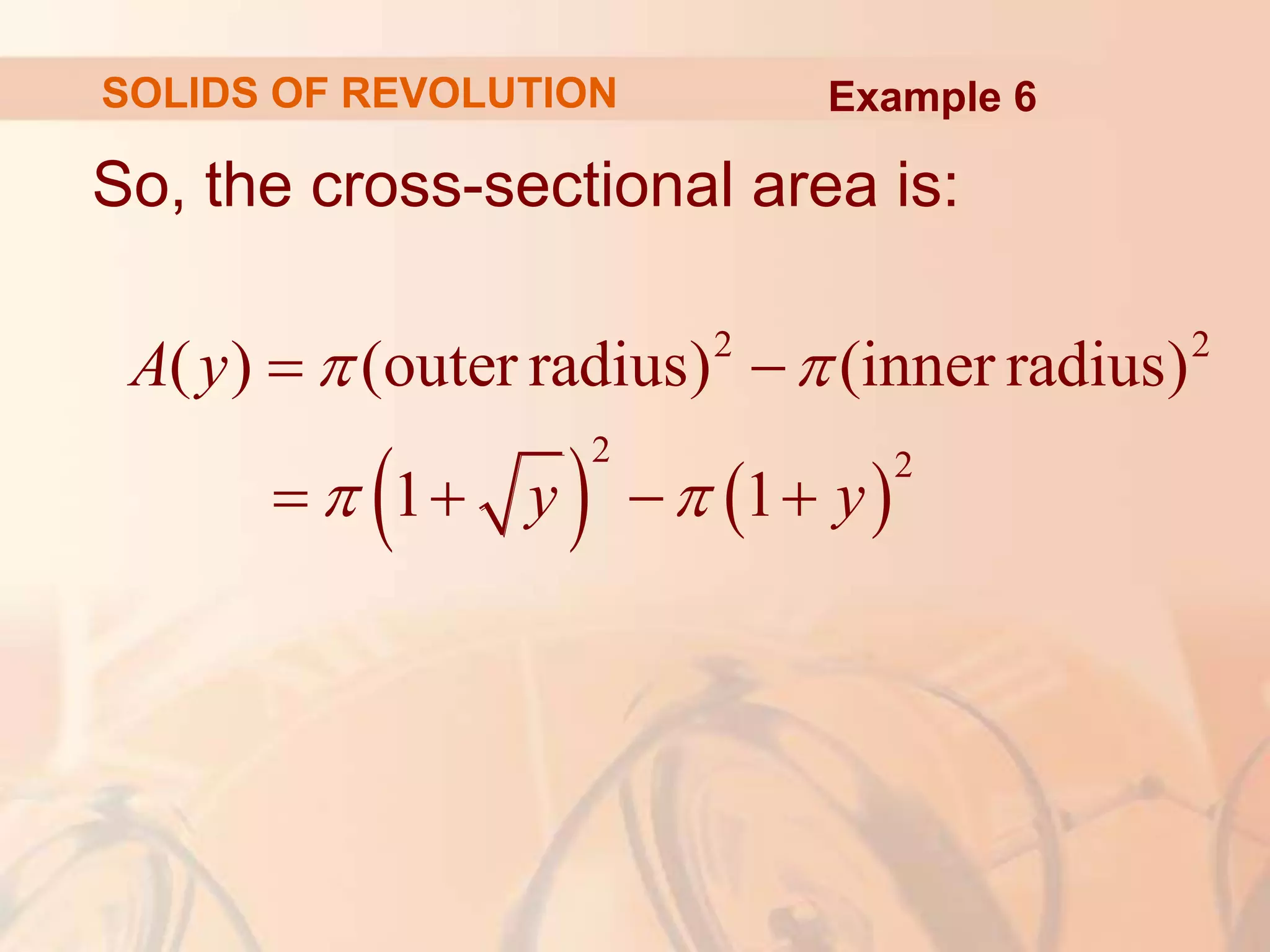

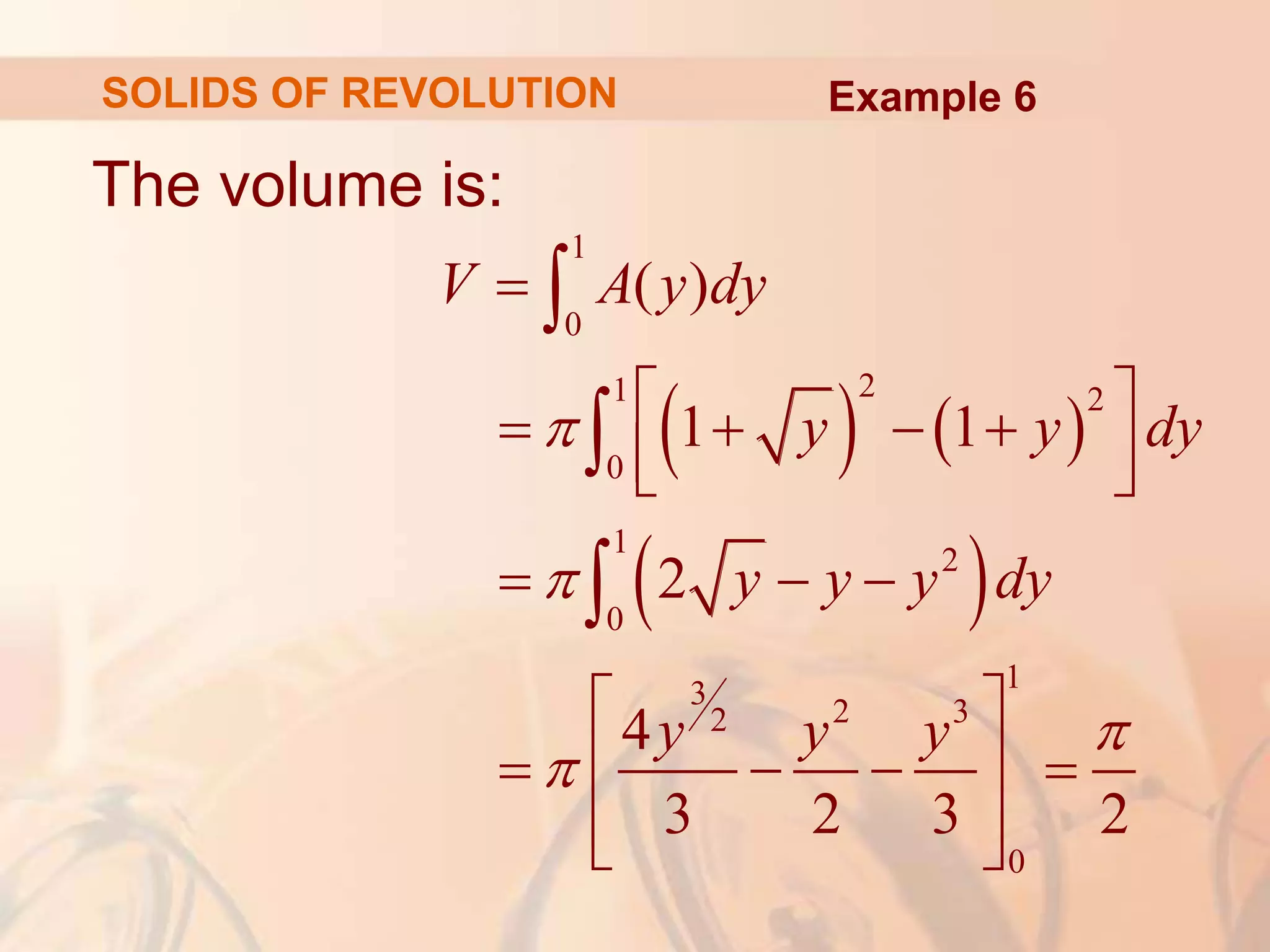

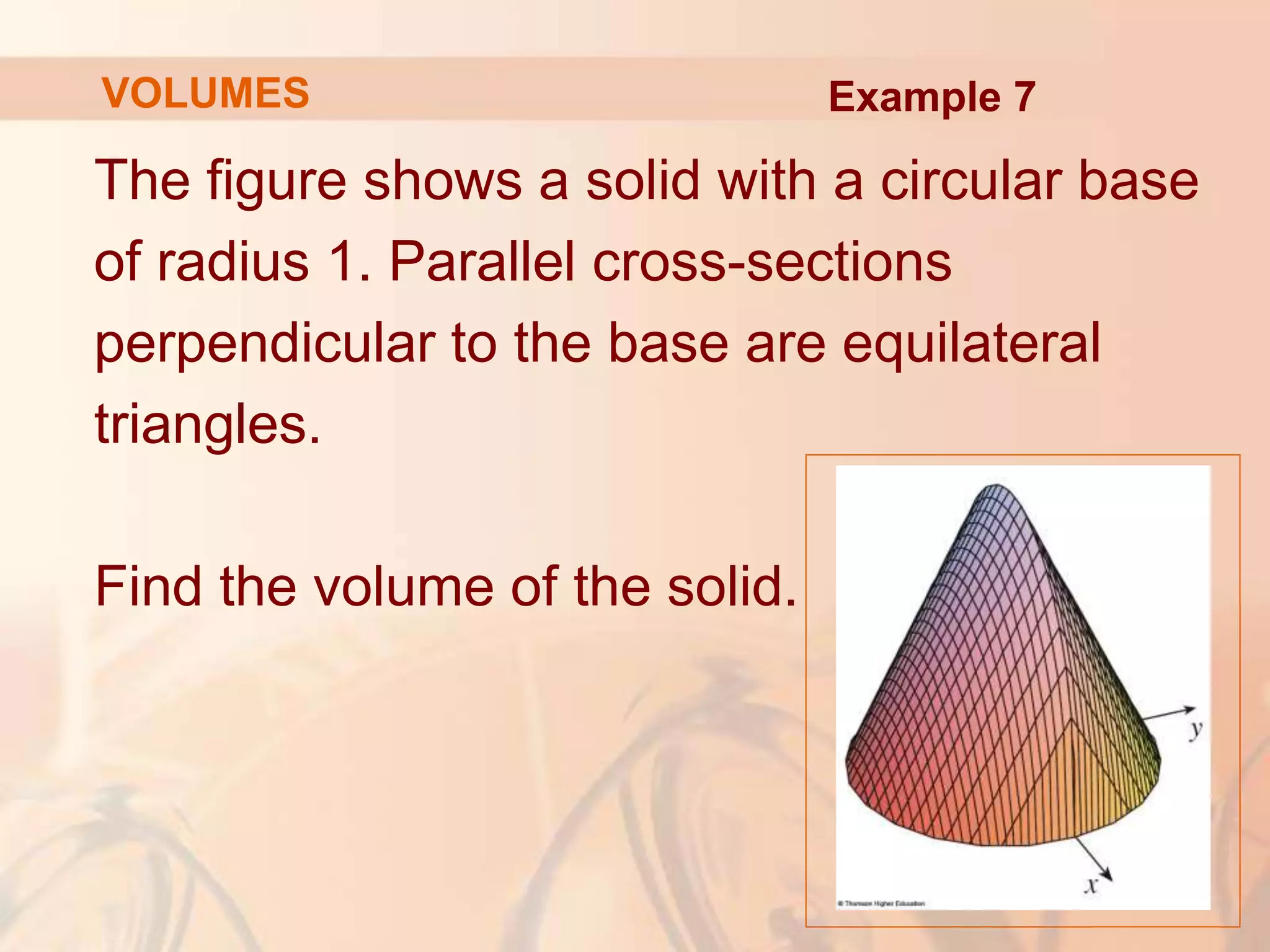

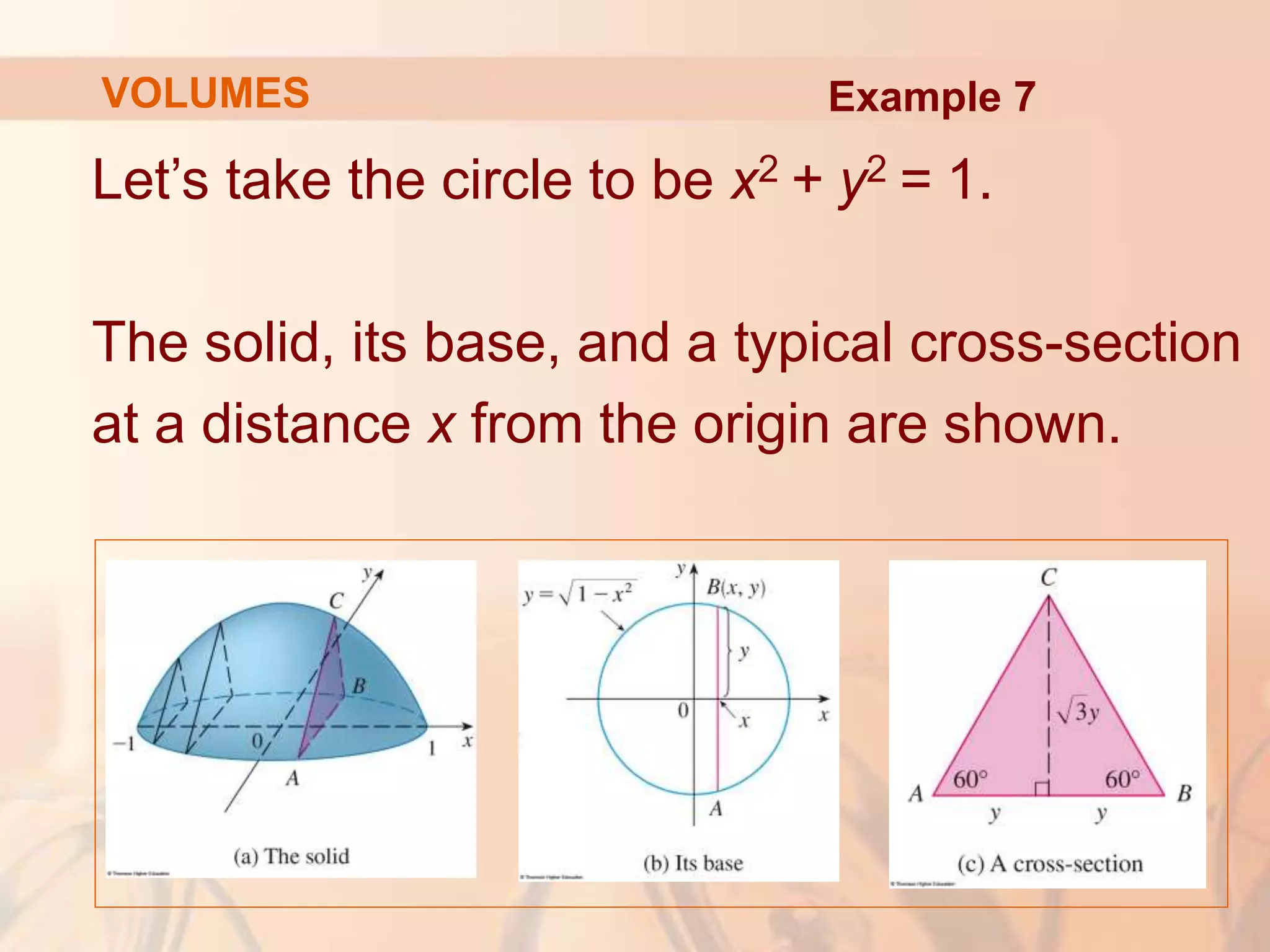

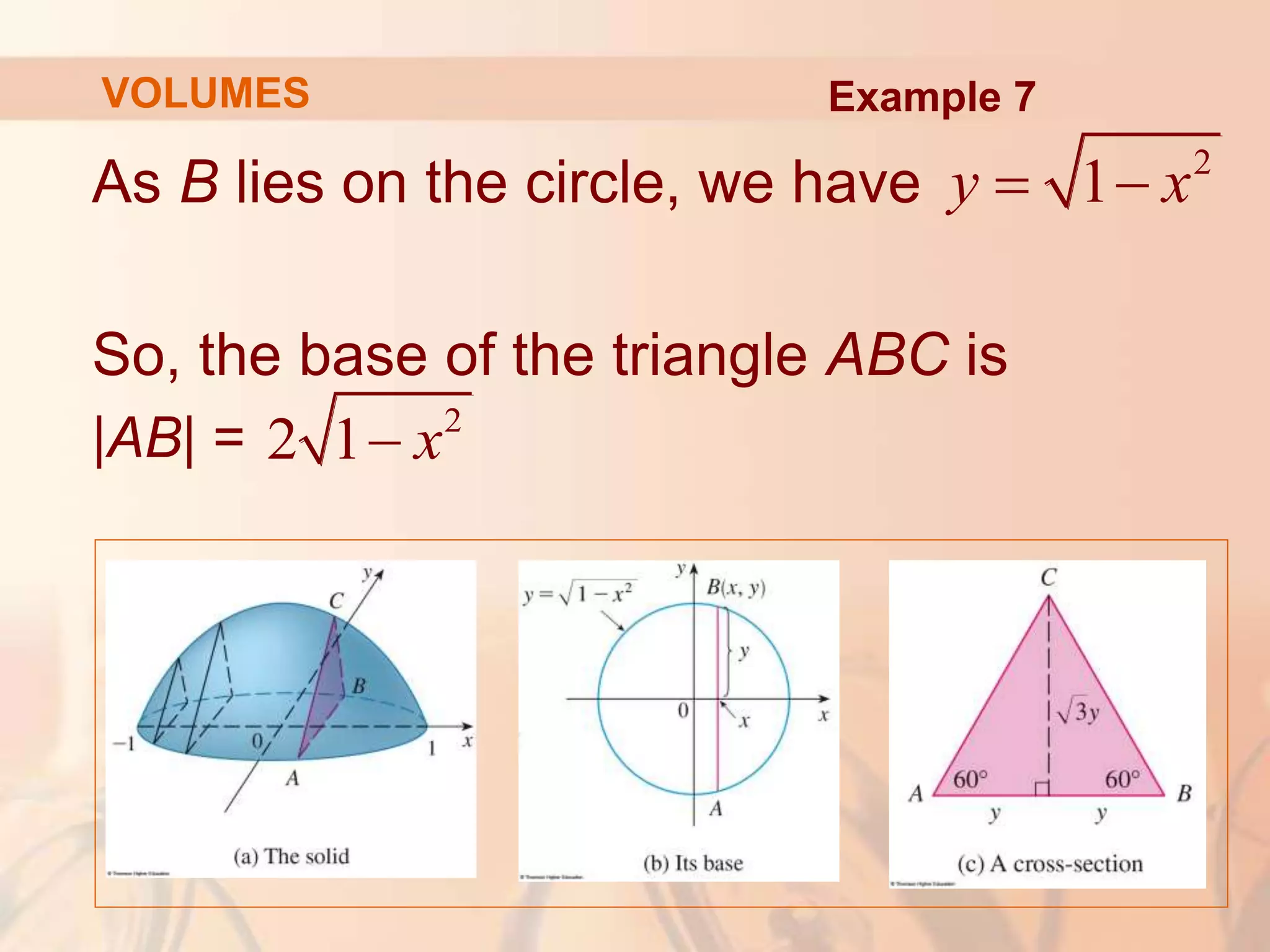

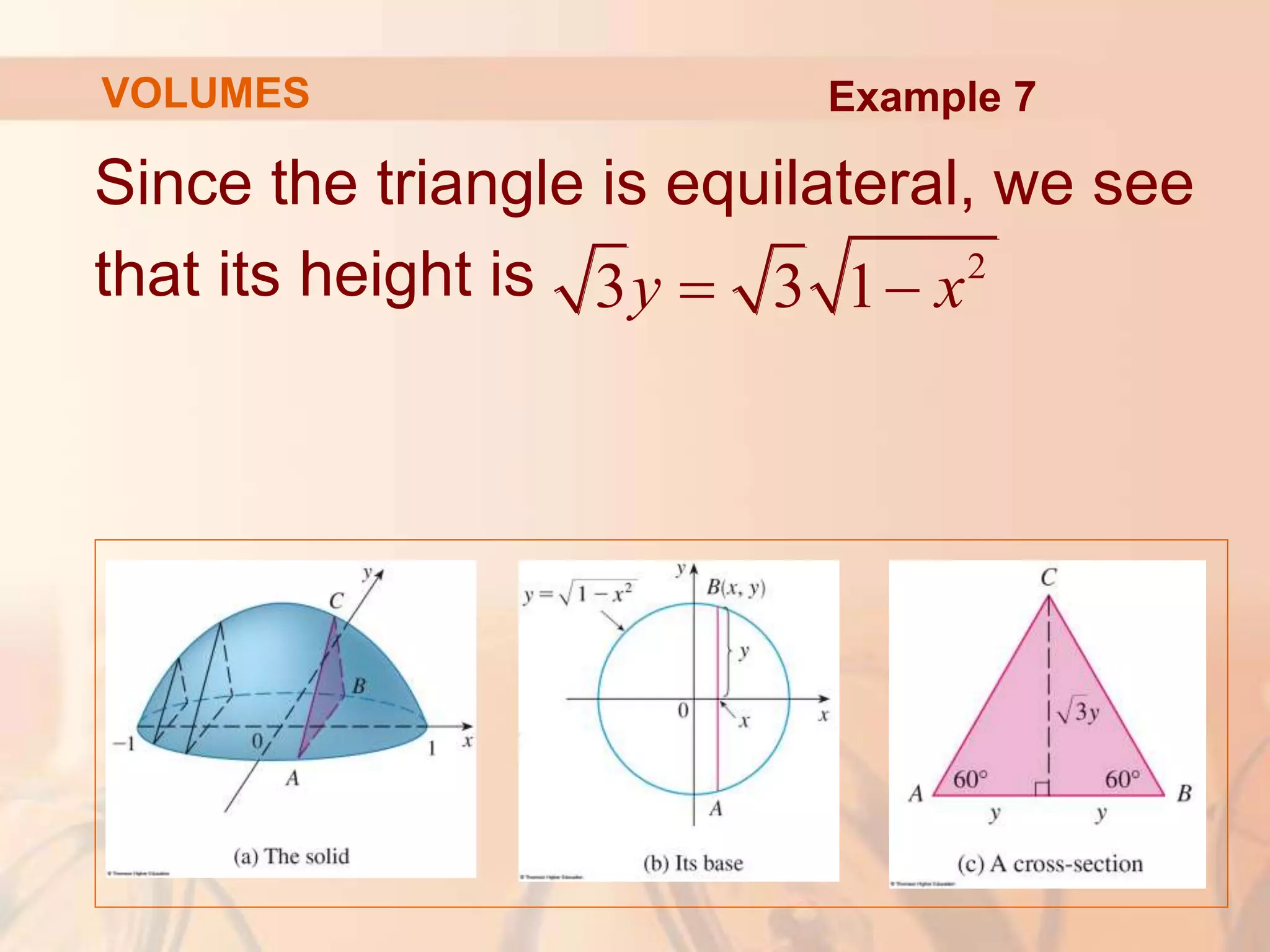

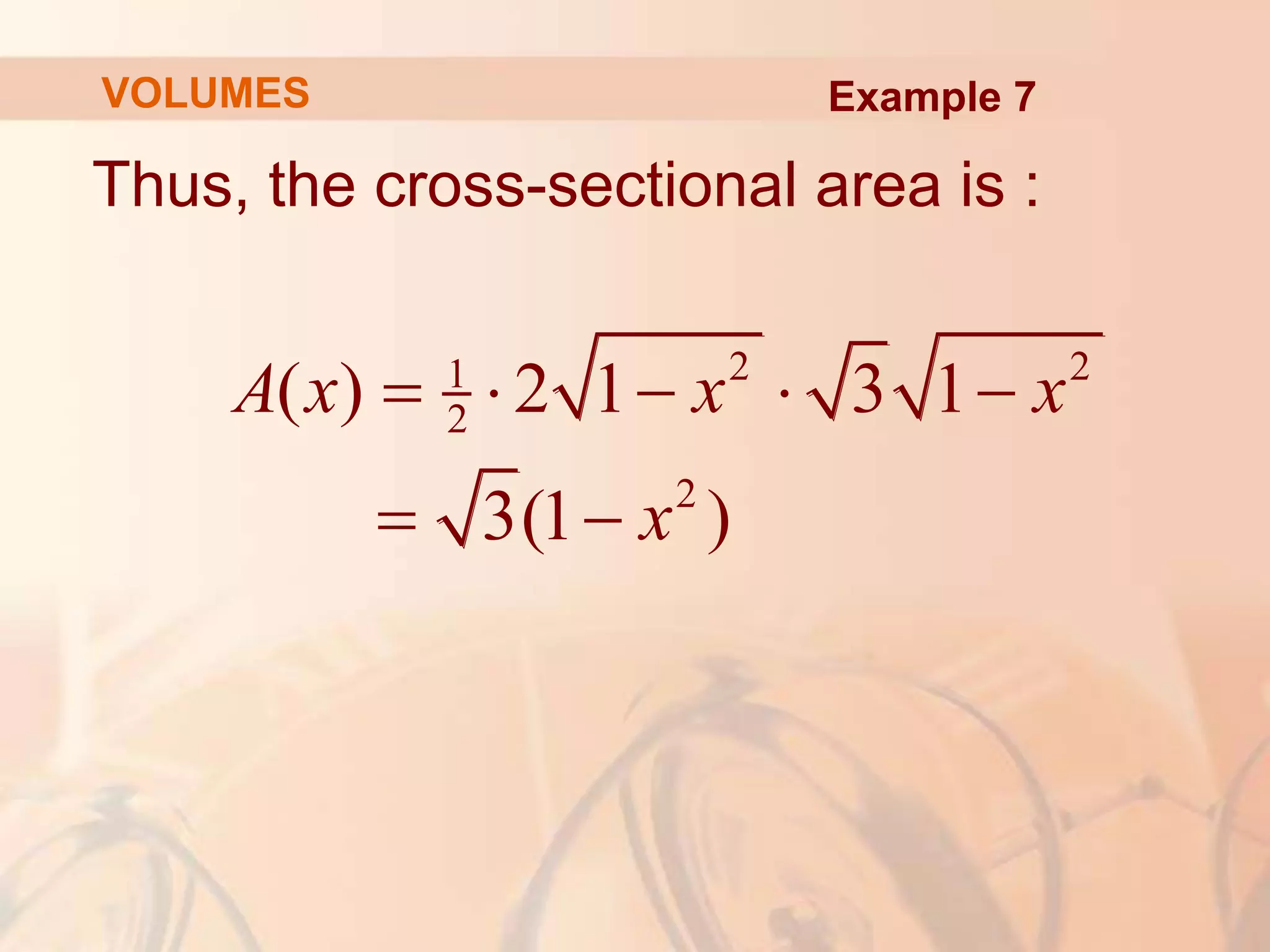

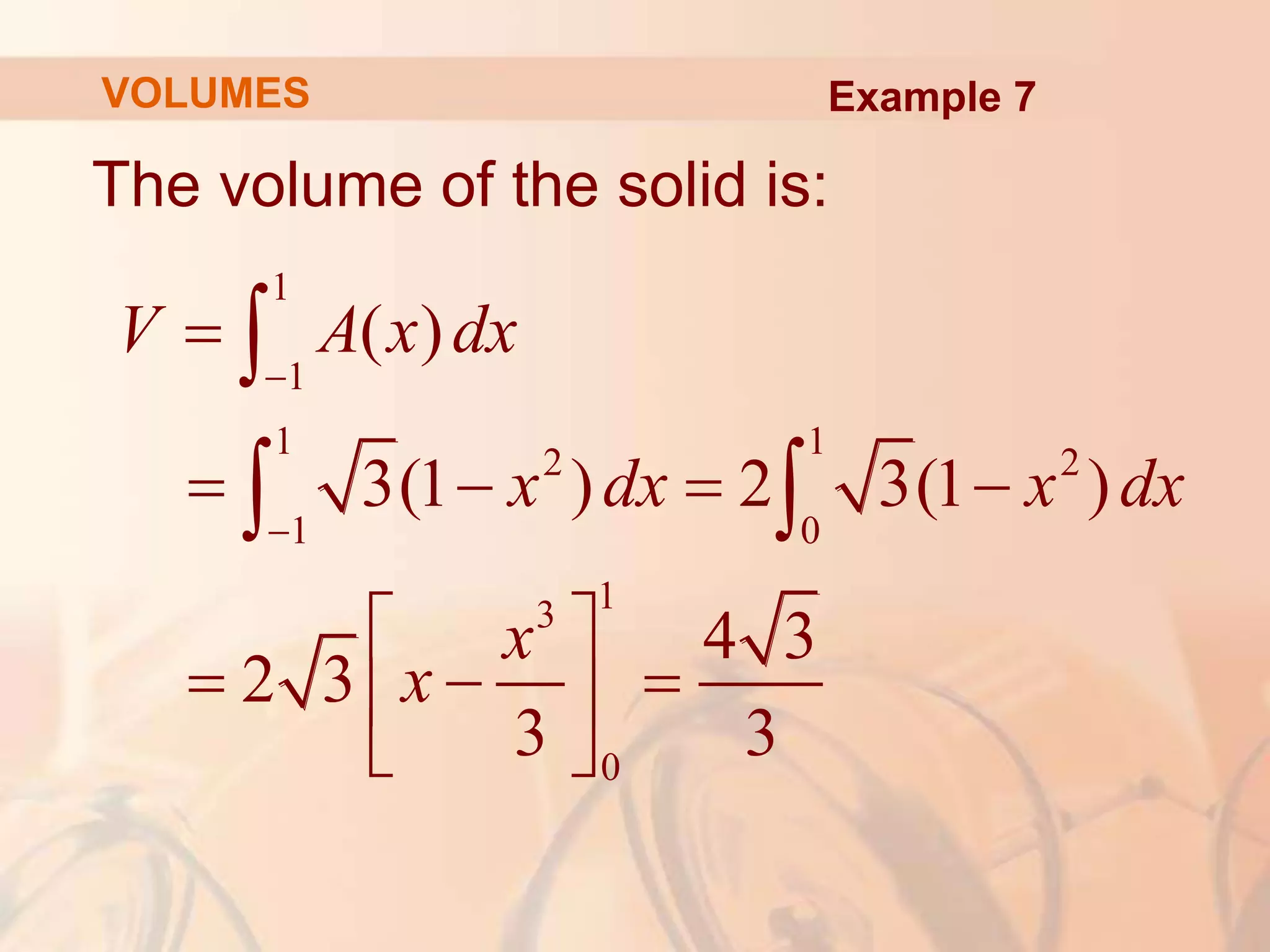

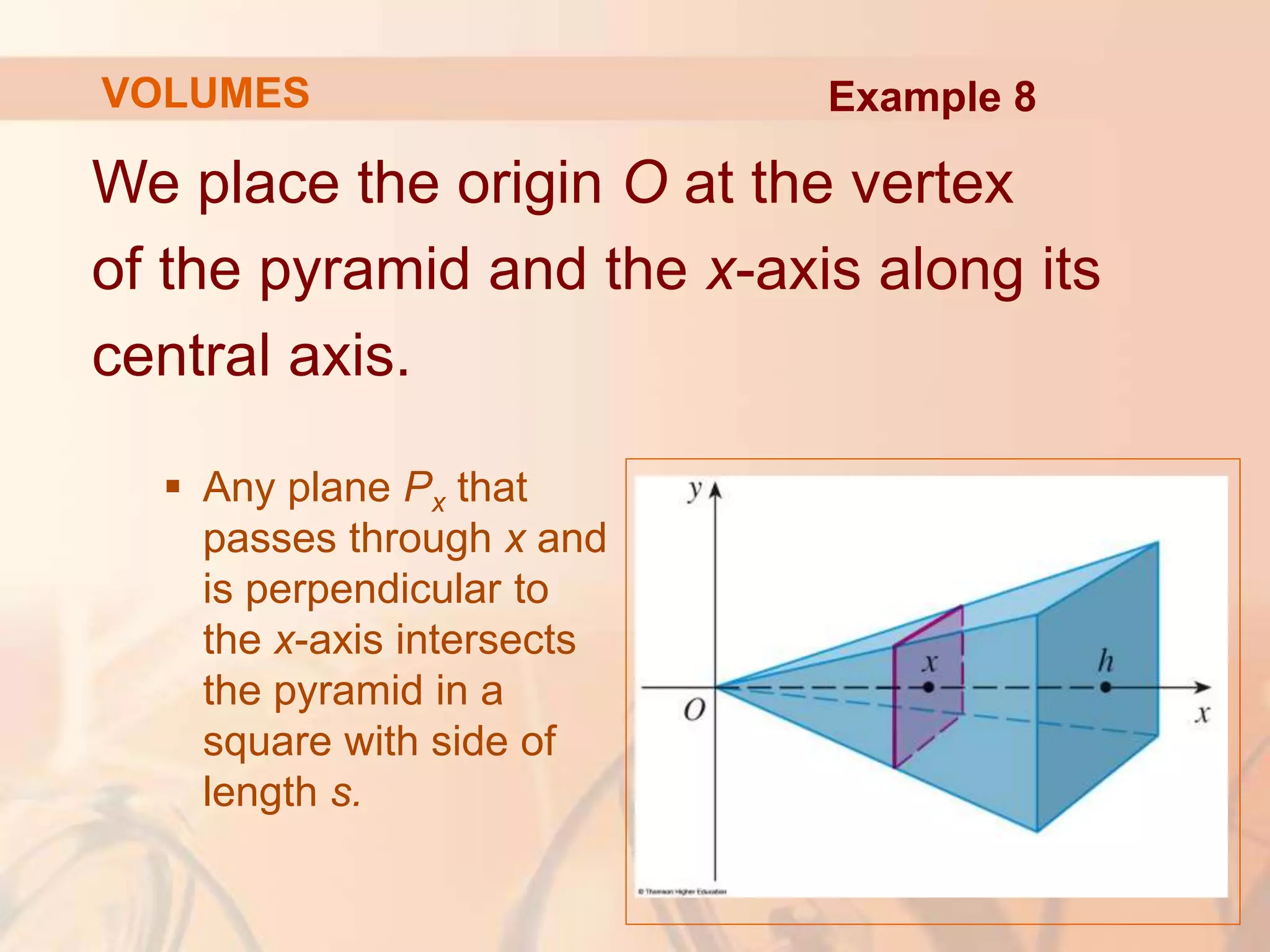

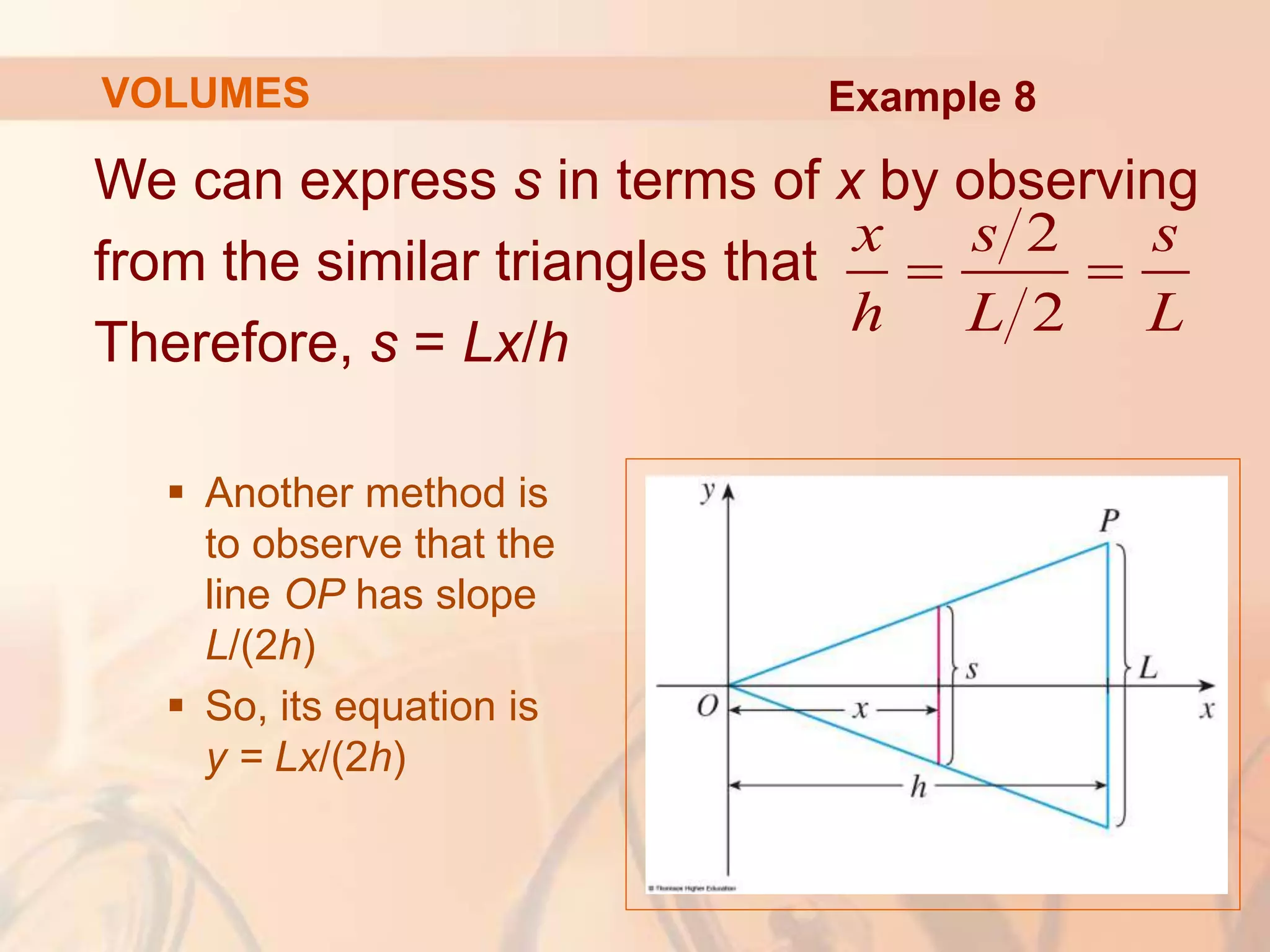

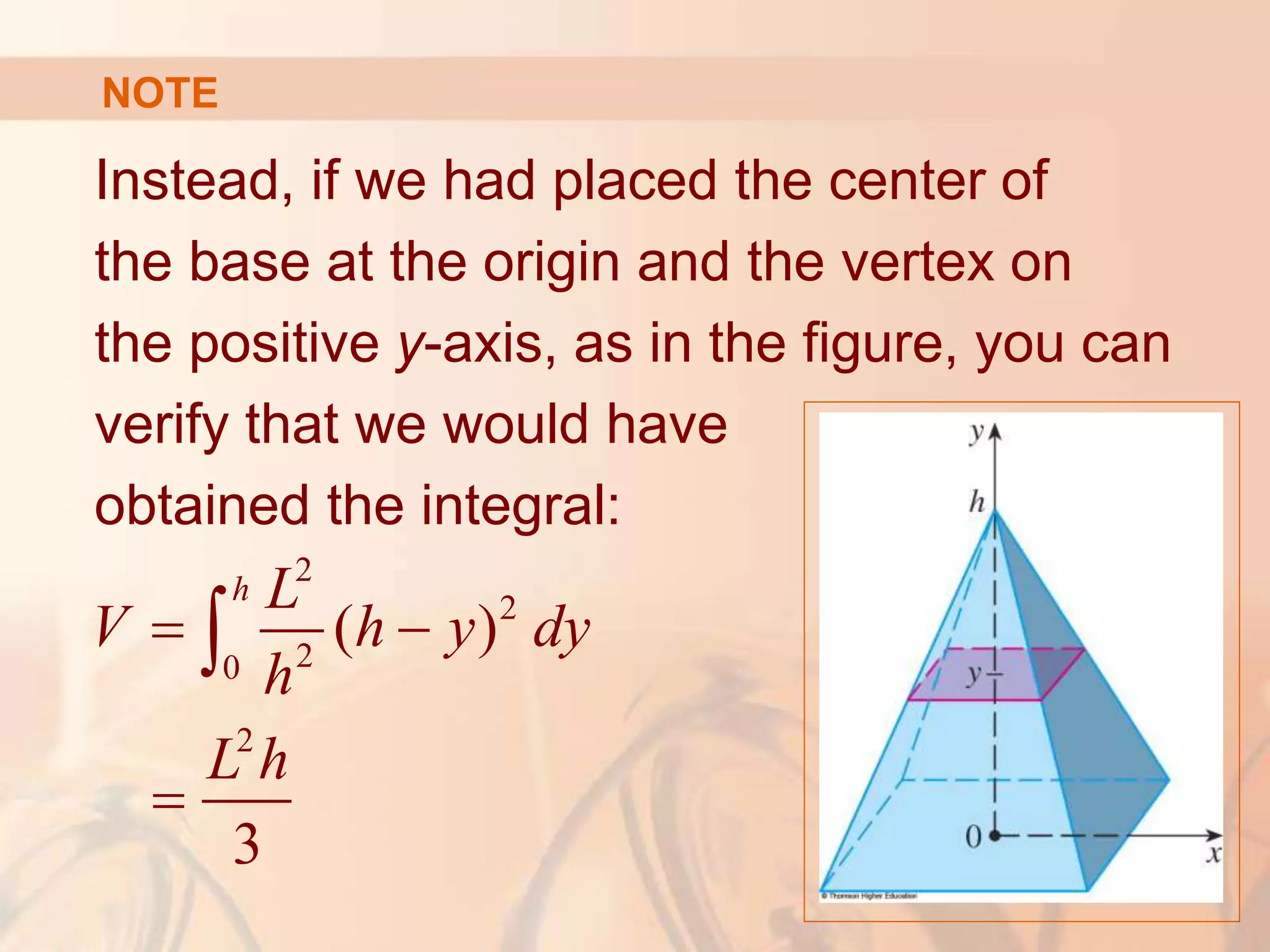

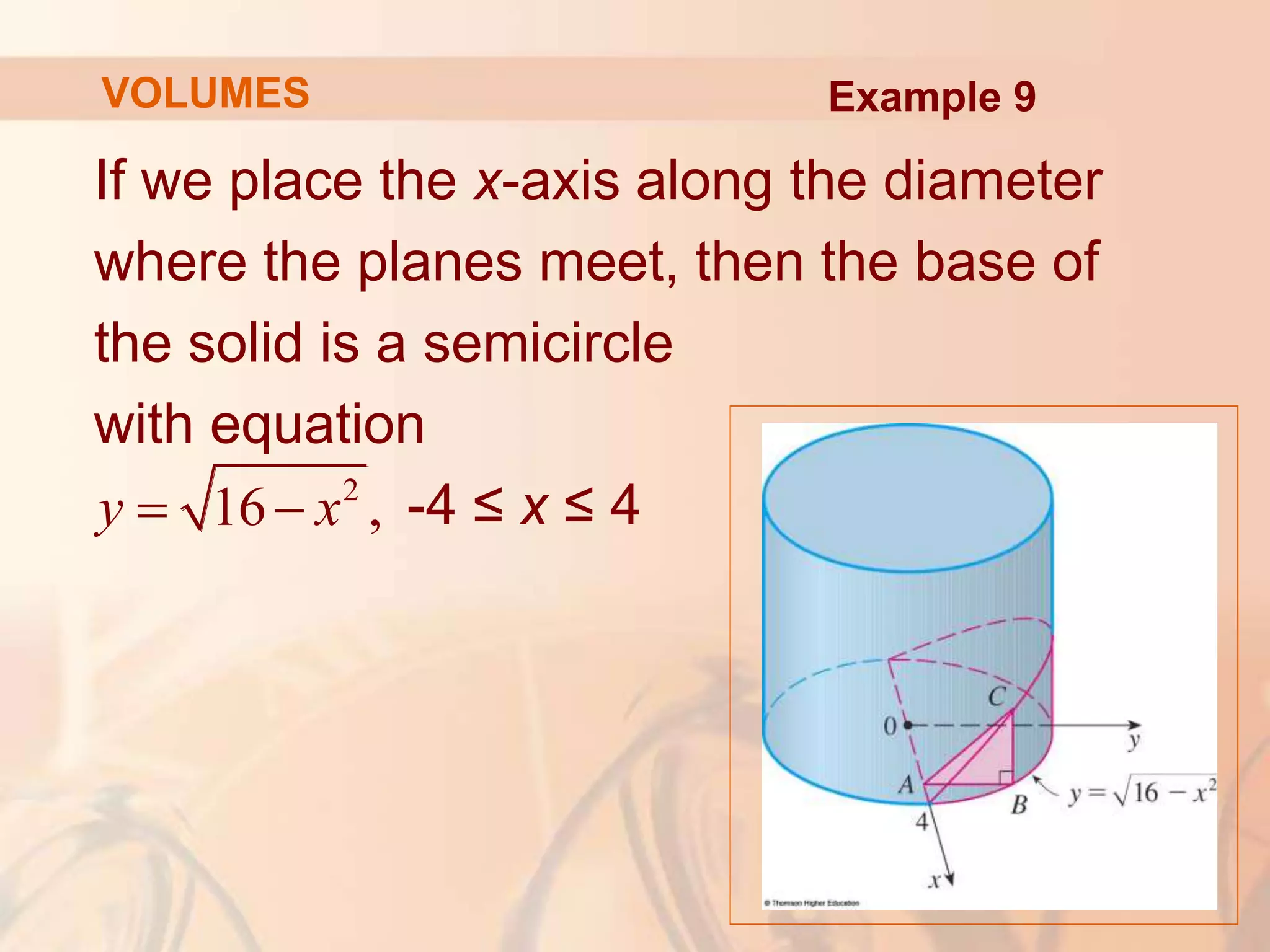

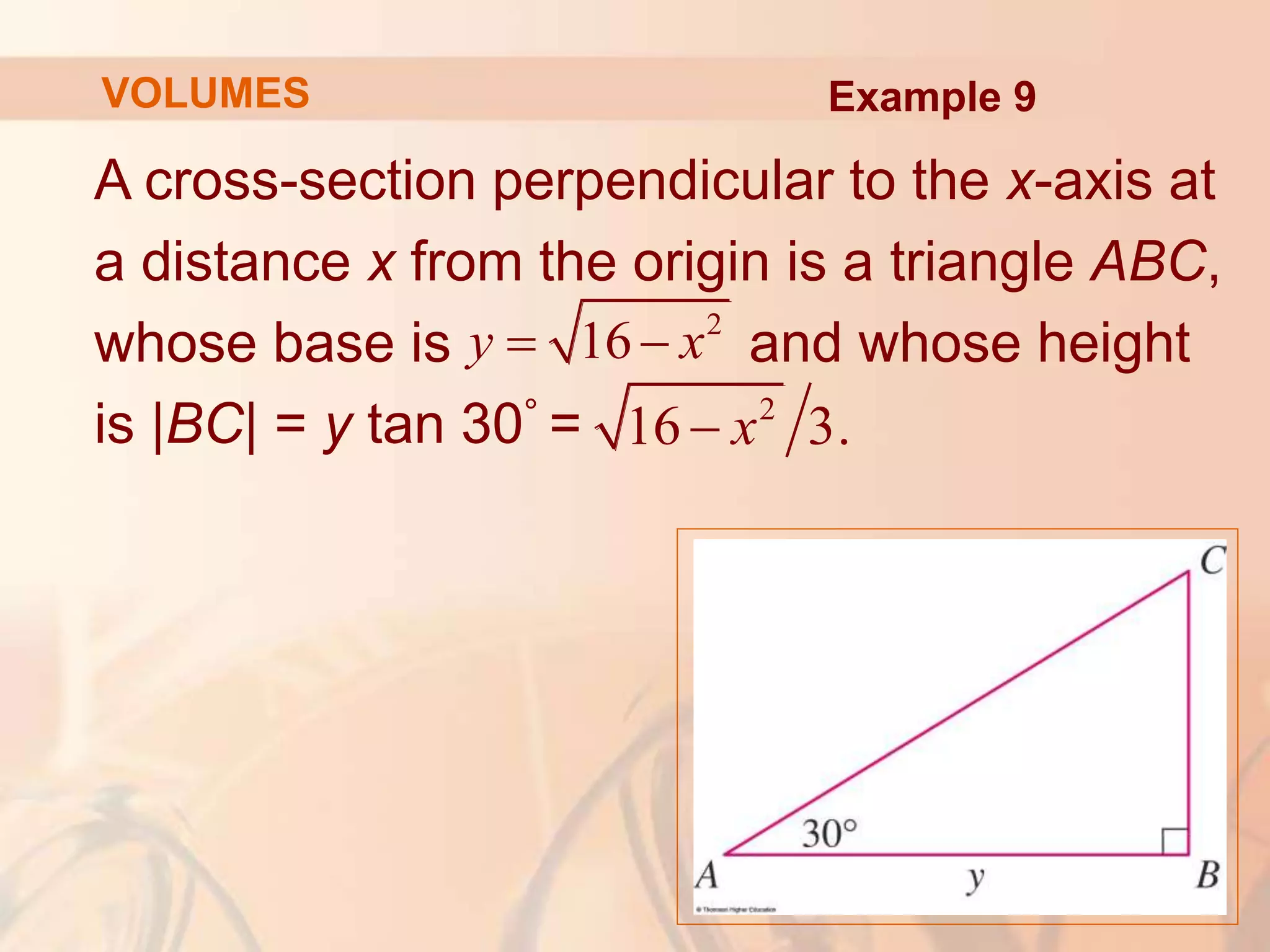

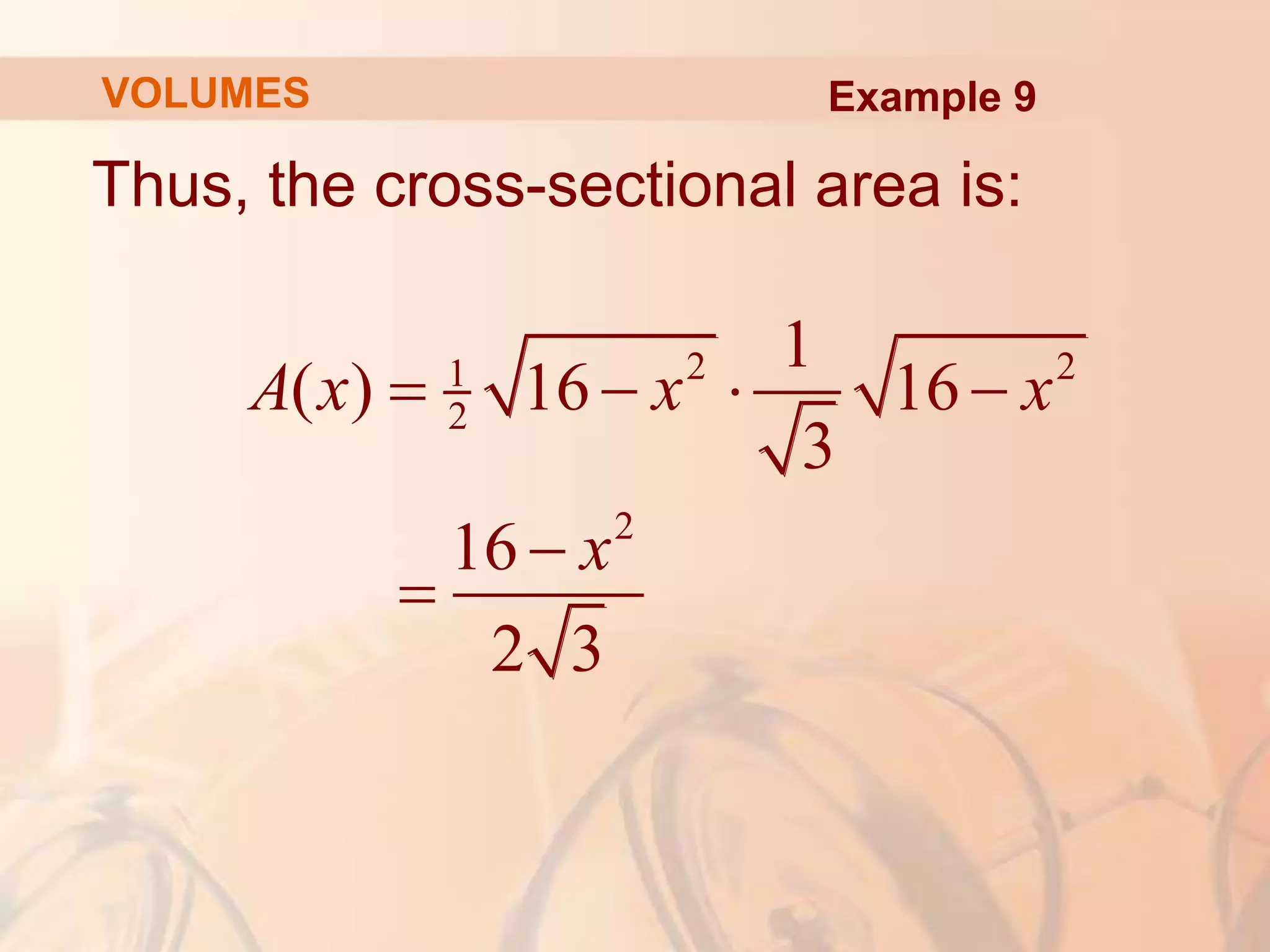

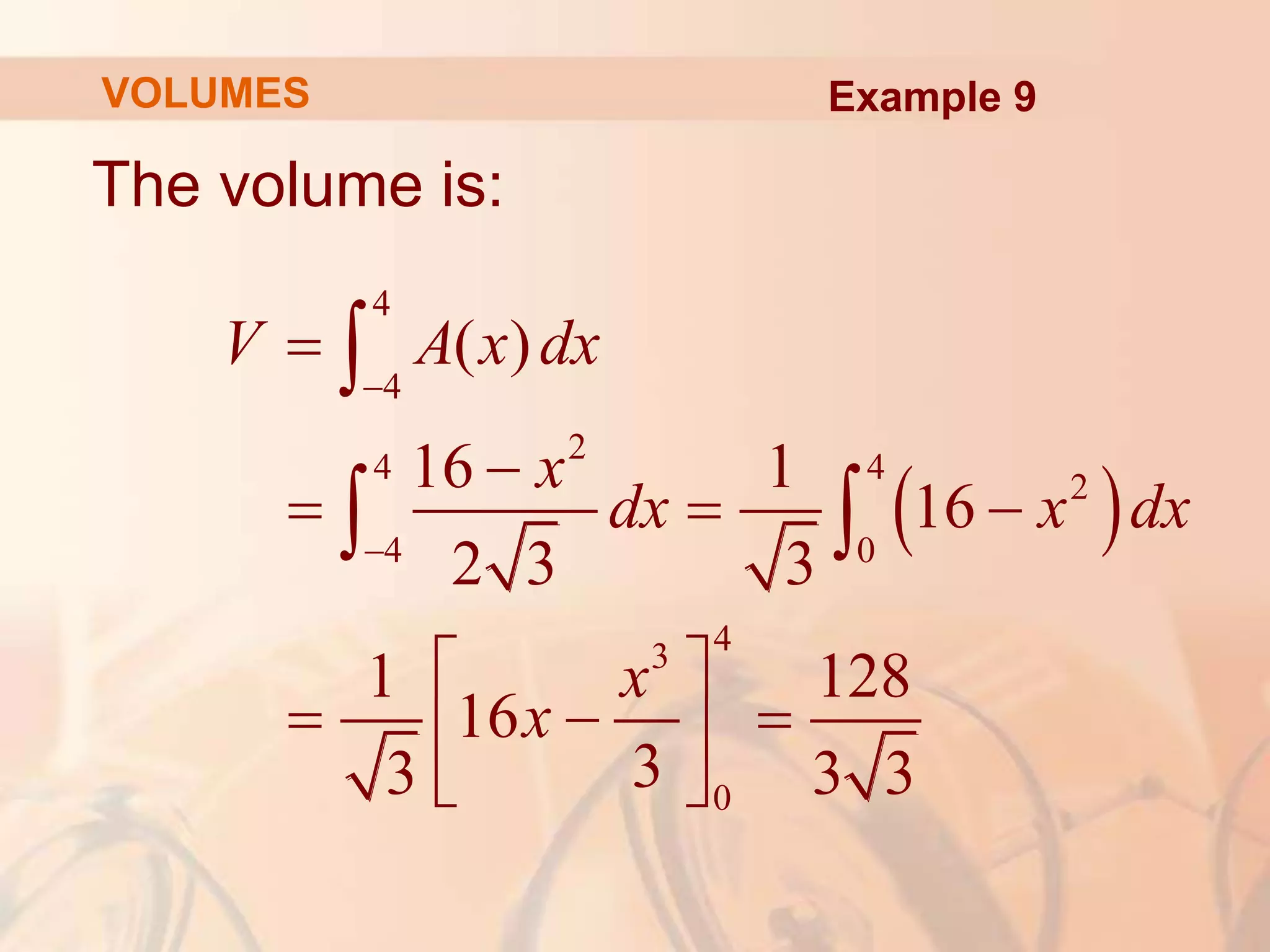

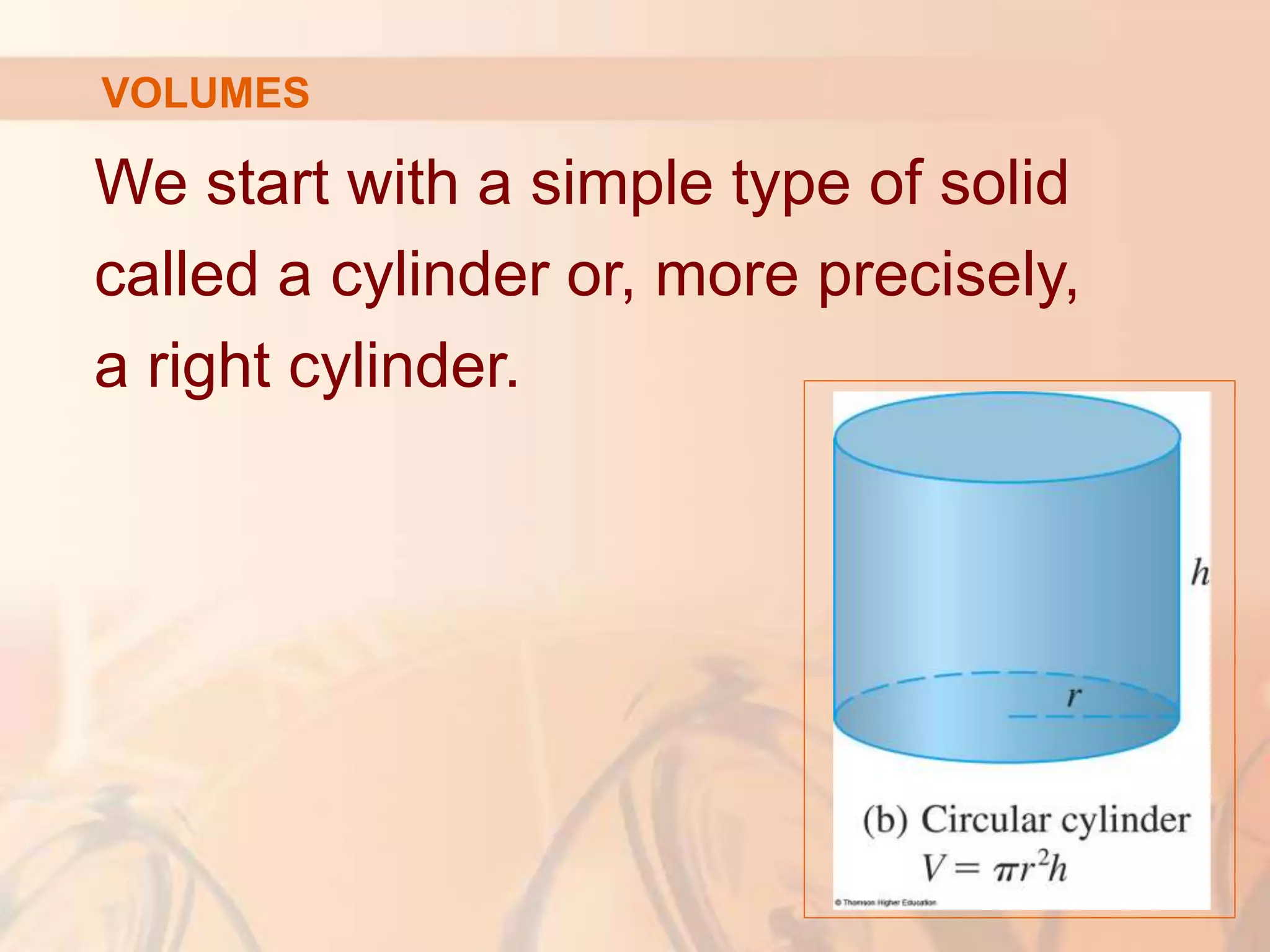

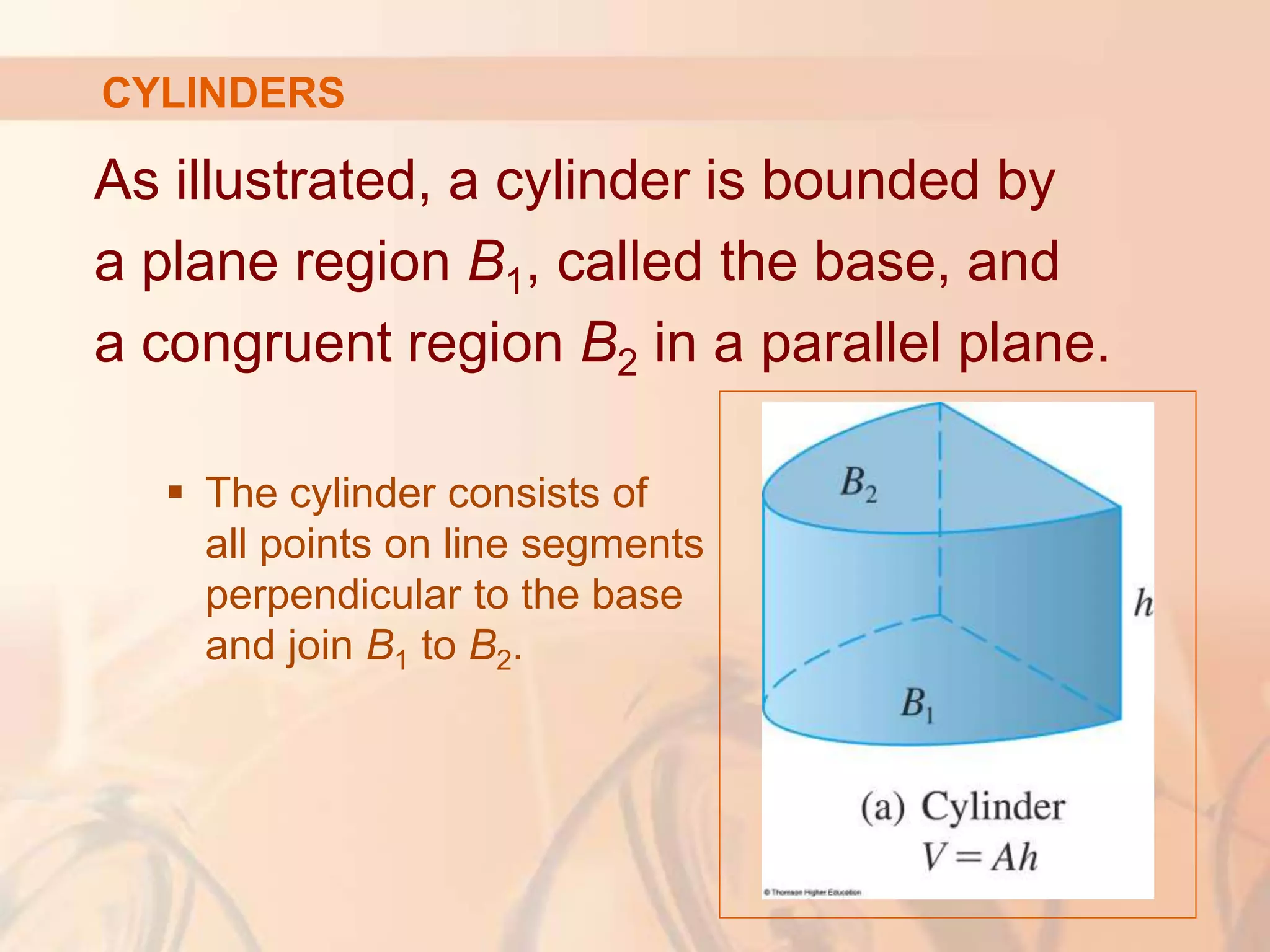

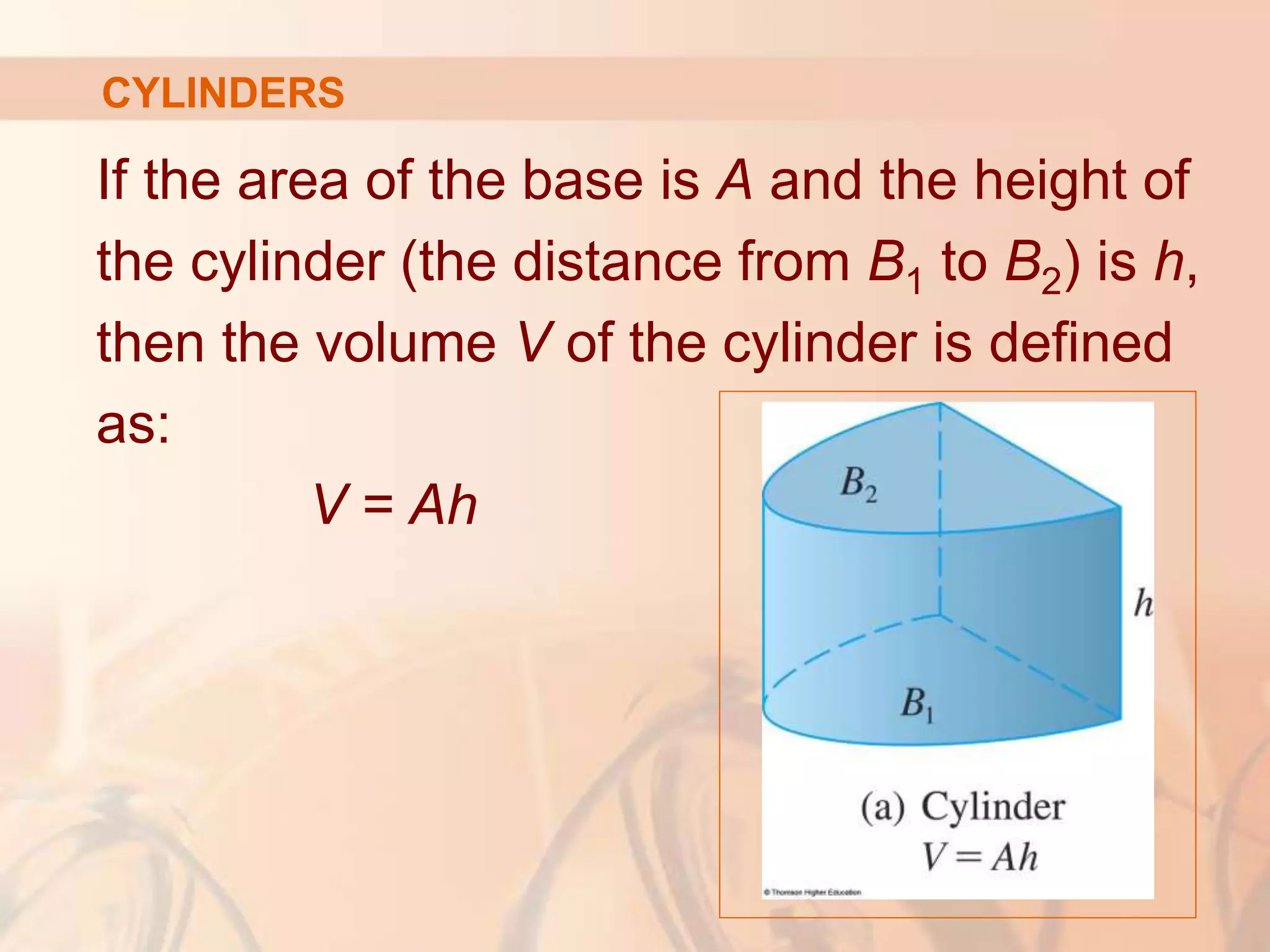

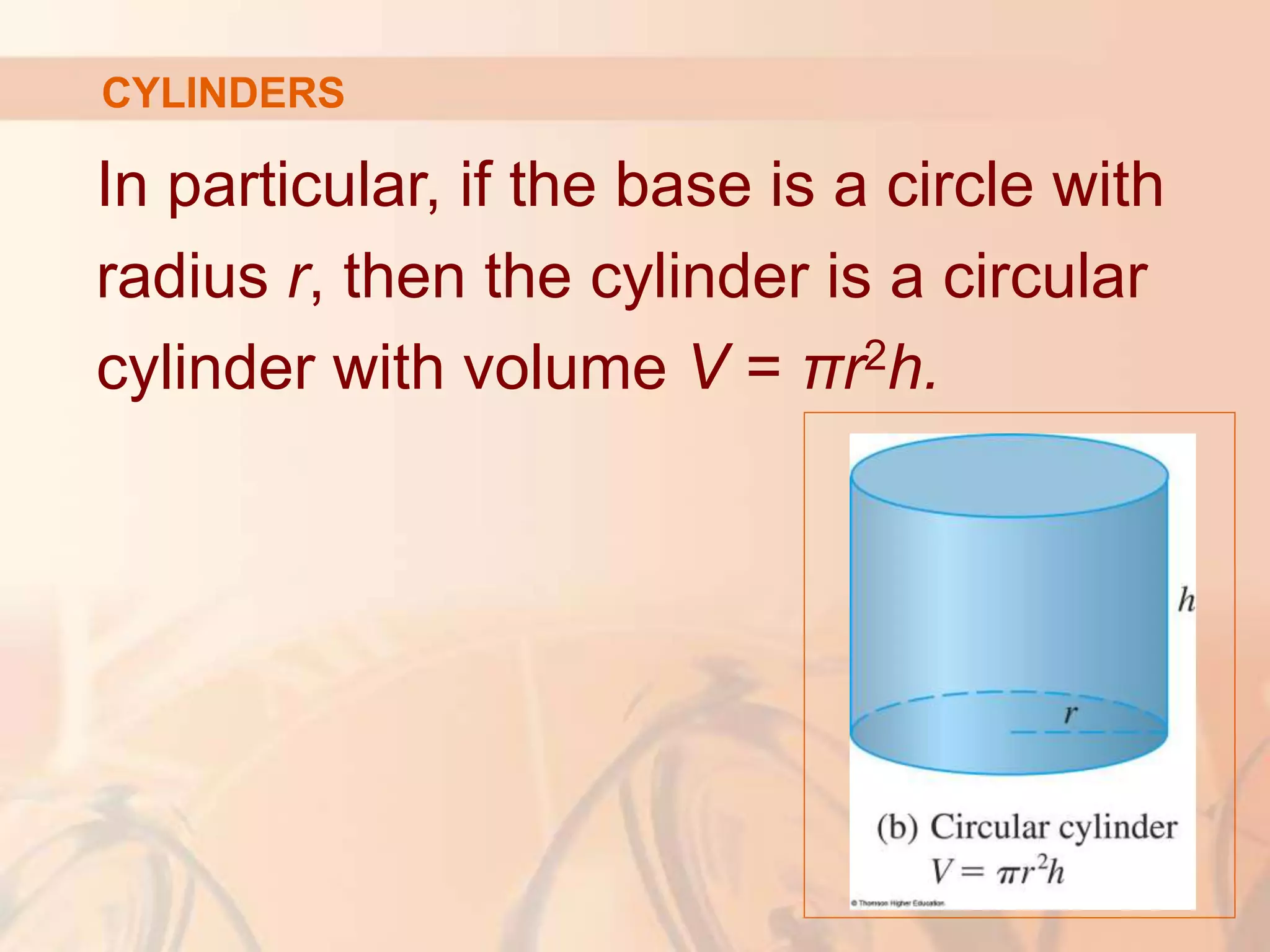

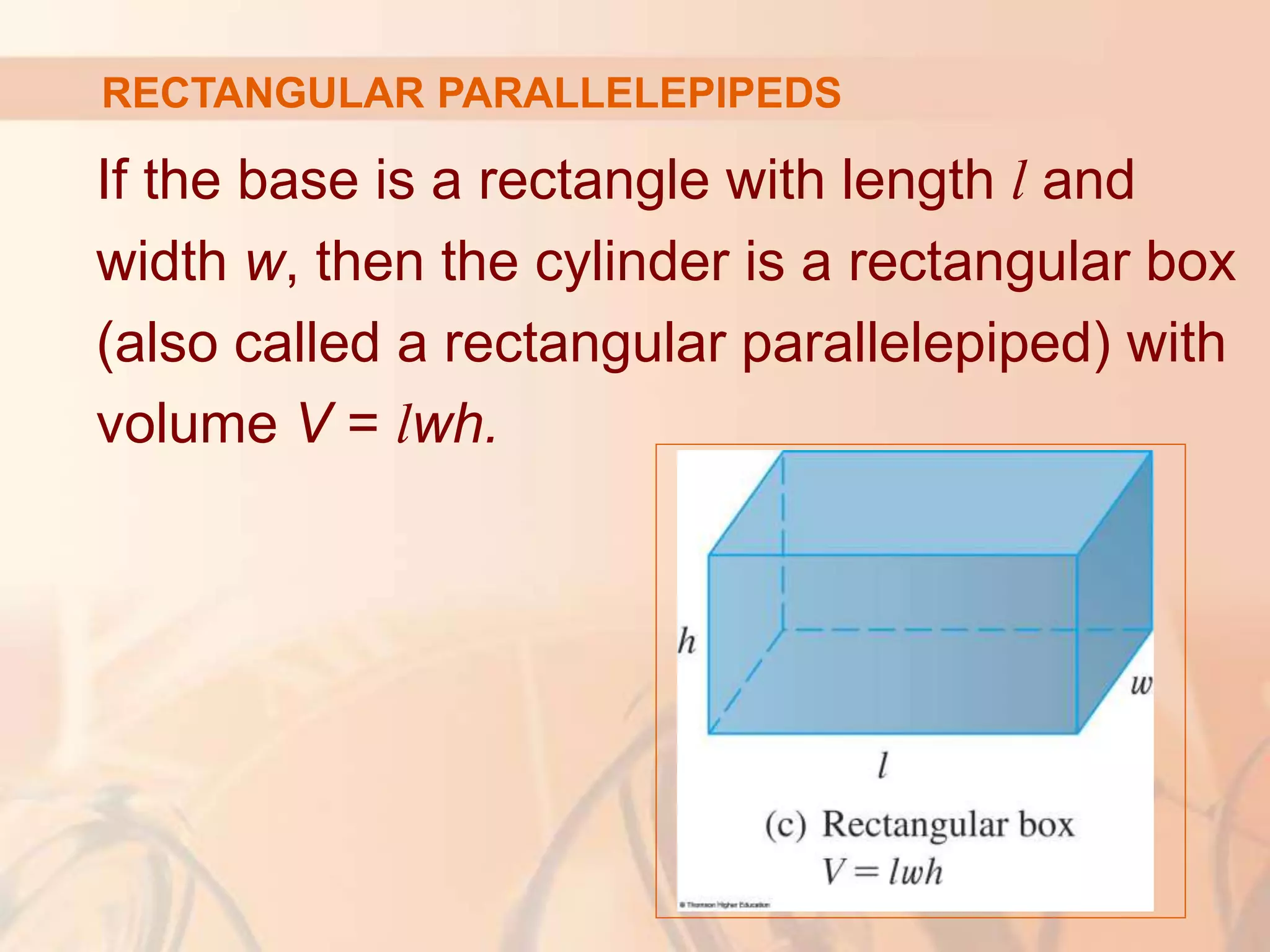

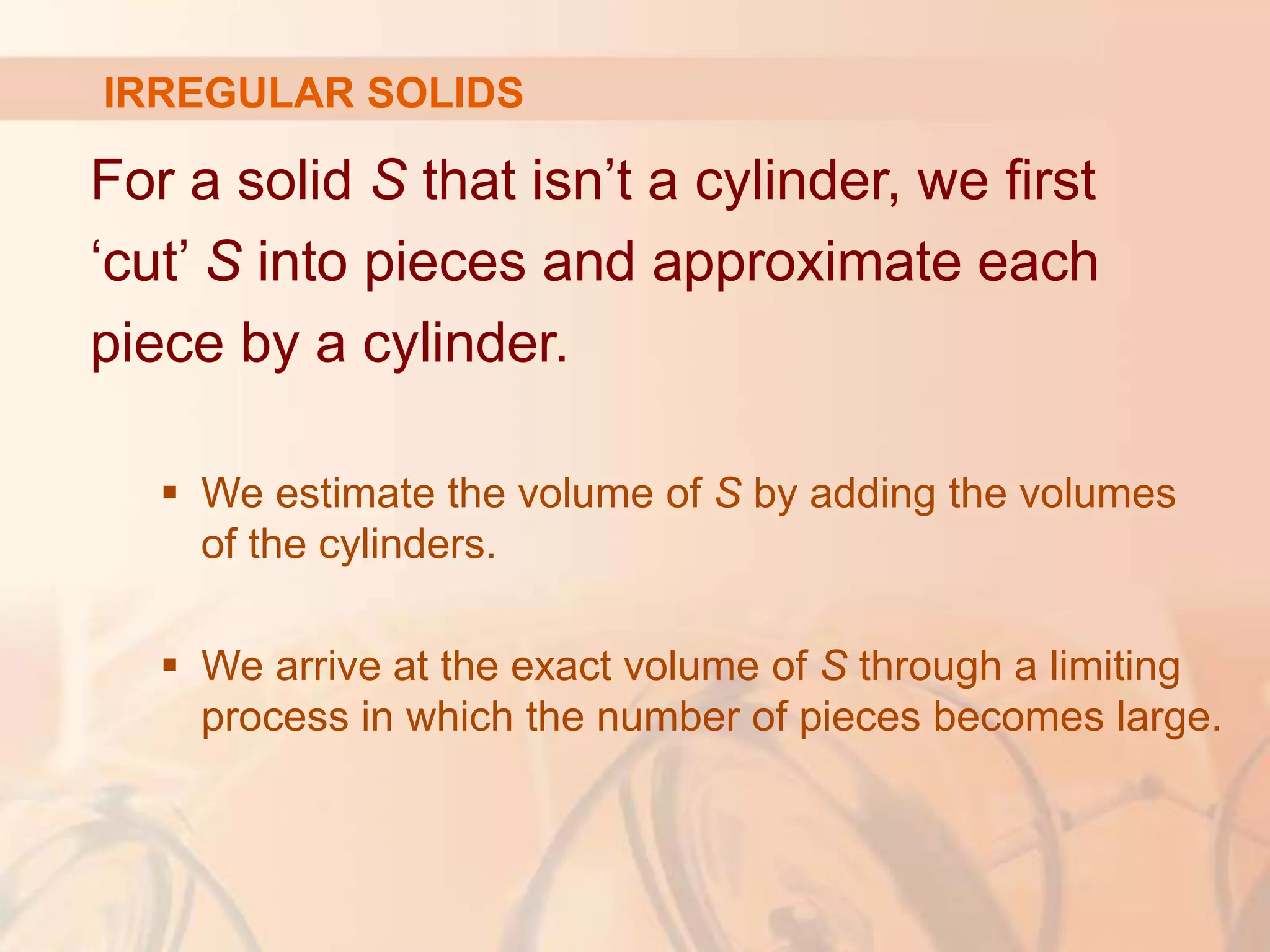

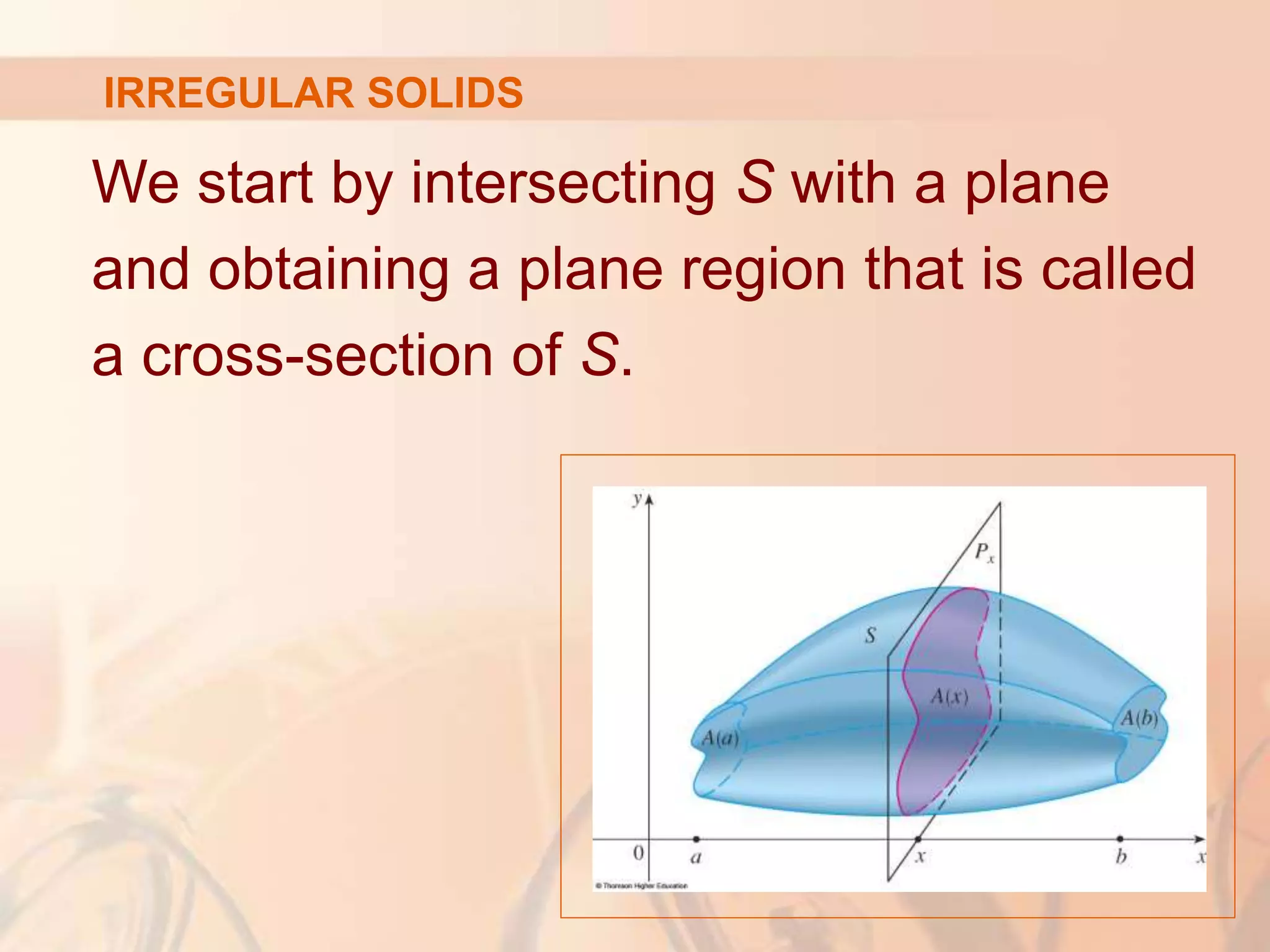

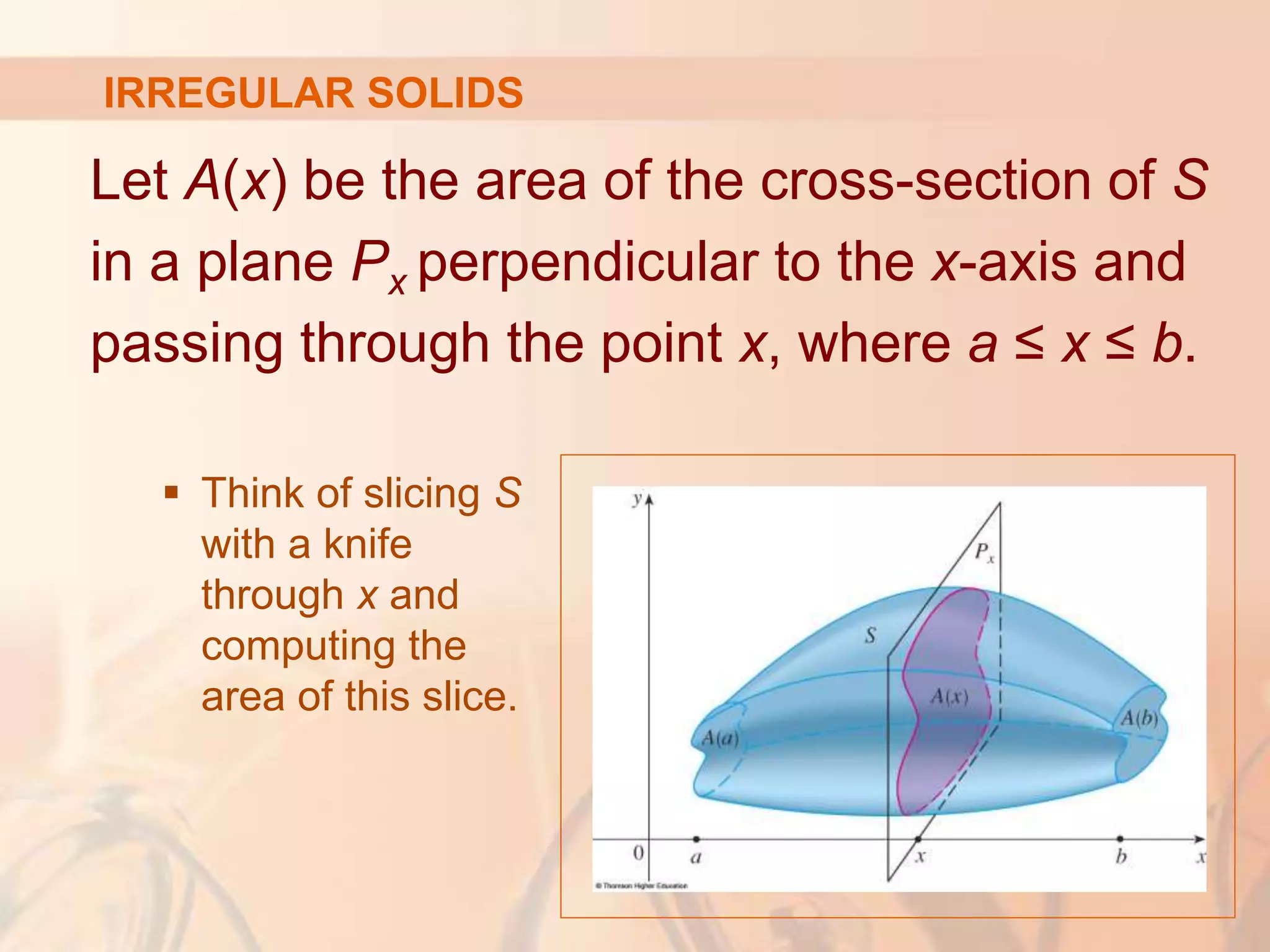

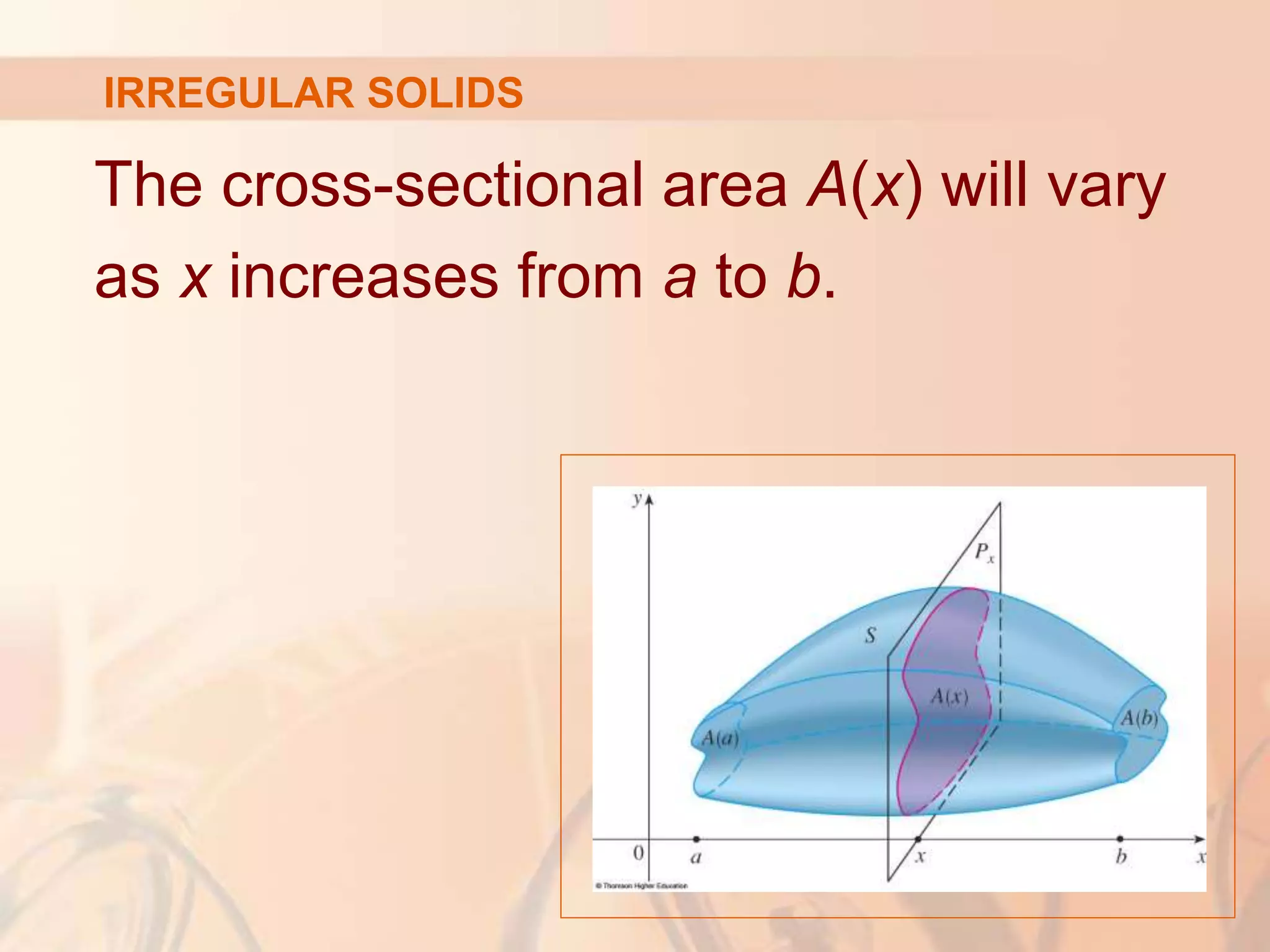

This document discusses calculating volumes of solids using integration. It begins by defining volumes precisely using calculus and cross-sectional areas. Cylinders are used as simple examples, where volume equals the area of the base times the height. Irregular solids are approximated as cylinders of infinitesimal thickness to define their volumes through integration. Several examples calculate volumes of solids obtained by rotating regions about axes, with disks or washers as cross-sections. The final examples calculate volumes without revolution by other methods.

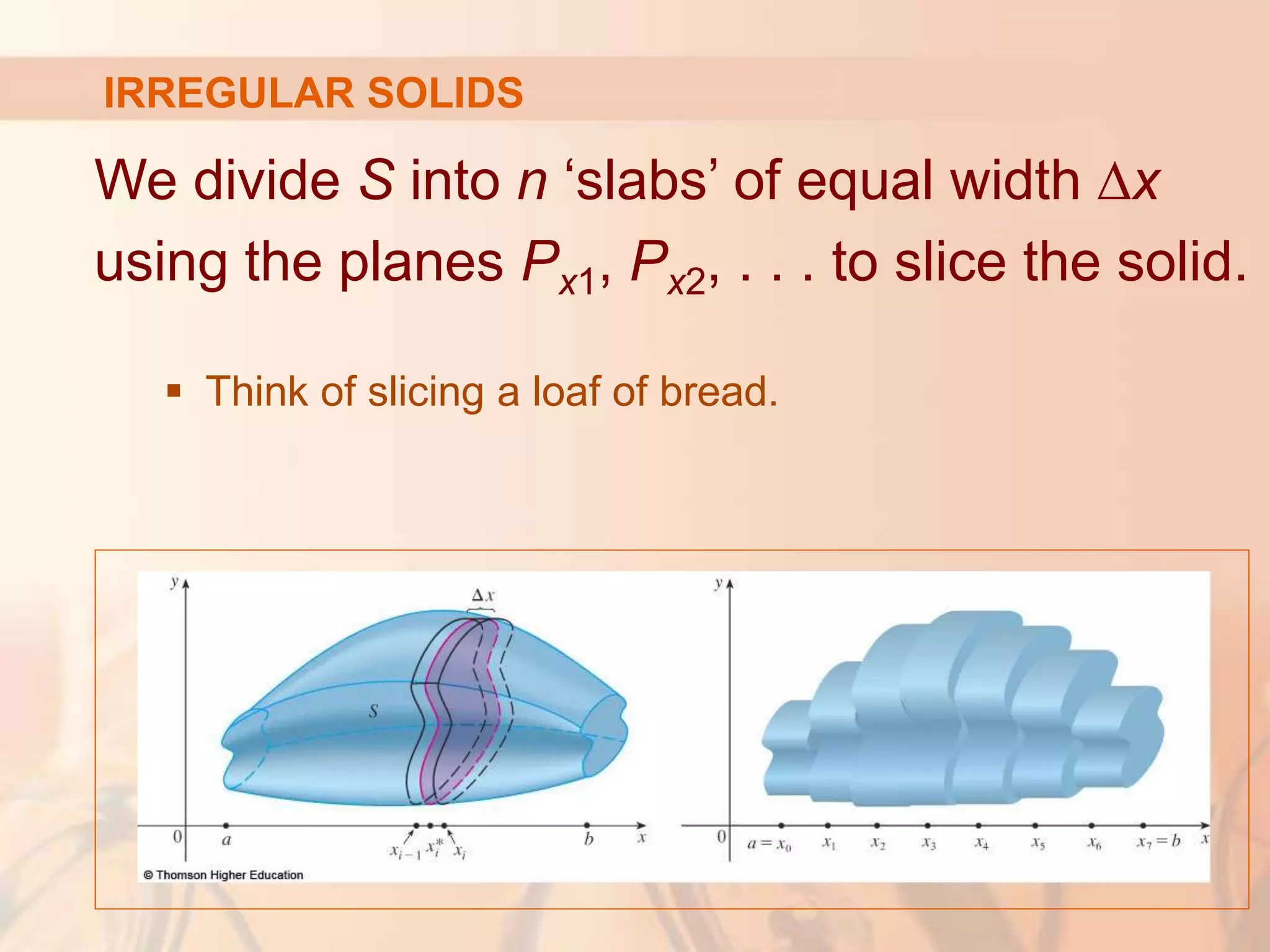

![If we choose sample points xi* in [xi - 1, xi], we

can approximate the i th slab Si (the part of S

that lies between the planes and ) by a

cylinder with base area A(xi*) and ‘height’ ∆x.

1

i

x

P i

x

P

IRREGULAR SOLIDS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chap6sec21-230320155707-c588f625/75/calculus-applications-integration-volumes-ppt-15-2048.jpg)