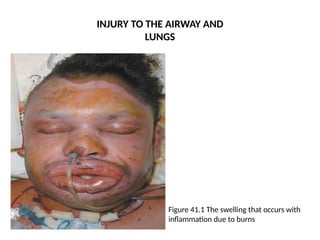

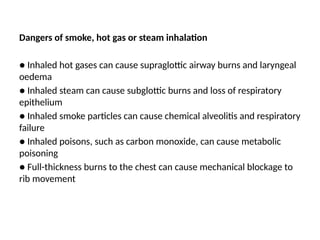

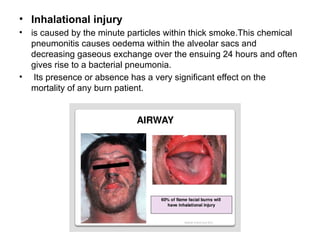

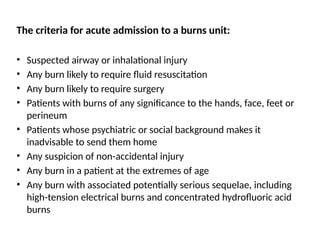

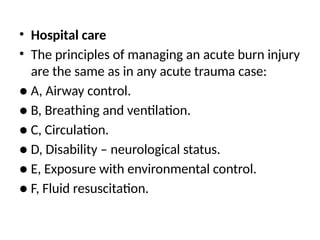

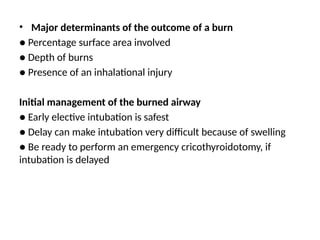

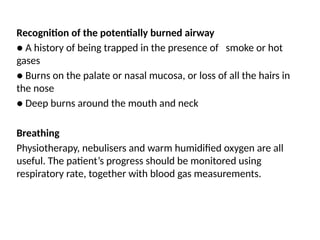

Burn injuries primarily affect the skin but can also damage the airway and lungs, leading to life-threatening complications if not treated properly. Immediate care involves stopping the burning process, cooling the wound, and assessing for inhalational injuries, with specific criteria for acute admission to a burns unit. Treatment includes fluid resuscitation, wound management, infection control, and, if necessary, surgical interventions for deeper burns.