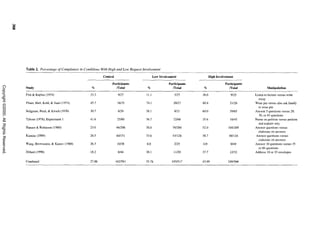

This document reviews research on the foot-in-the-door (FITD) social compliance technique. It identifies several psychological processes that may influence compliance in a FITD situation, such as self-perception, reactance, conformity, consistency, attributions, and commitment. Some processes increase compliance while others decrease it. The effectiveness of FITD depends on the relative strength of these different processes. The review examines studies that meet criteria for a clear FITD manipulation and finds the technique reliably but modestly increases compliance. However, explanations beyond self-perception may be needed to understand all FITD results.

![BURGER

reviews also pointed out that the size of the effect is Psychological Processes Affecting

relatively small (overall r range = .09-.17). Also, FITD Outcomes

none was able to identify and explain the circum-

stances under which failure to produce the effect or We begin by identifying several psychological pro-

reversals of the effect are most likely to occur. cesses that theoretically playa role in participants' re-

The reviewers' conclusions about the process un- actions to the basic FITD manipulation. The list of

derlying the FITD phenomenon also are a bit mixed. potentially relevant processes is presented in Table 1.

As described in greater detail later, the generally ac- This multiprocess analysis contrasts with the typical

cepted explanation for the effectiveness of the FlTD approach taken to explain the FlTD effect. That is, re-

procedure is that participants engage in an atti- searchers and reviewers trying to explain the mecha-

tude-change process similar to that outlined in nisms underlying the phenomenon have tended to

self-perception theory (Bem, 1972). Although several search for a single process to account for the different

studies have provided results consistent with findings. For most of the history of FITD research, this

self-perception theory, other findings are not easily single process has been identified as the self-

accounted for with this explanation (Dejong, 1979; perception explanation. However, we argue that

Gorassini & Olson, 1995). One team of reviewers self-perception is but one process potentially set in mo-

(Dillard et aI., 1984) concluded that the self- tion by the initial request. Moreover, the impact of this

perception explanation "come[s] up short" (p. 484). self-perception process may be relatively weak. That

Another (Beaman et al., 1983) suggested that "[iJt is, more powerful psychological processes also may be

may well be that rself-perception] theory is only a operating in a given FITD situation, and these can

partial explanation accounting for only some of the overwhelm whatever impact self-perception has on the

variance" (p. 192). ultimate decision to agree with the target request.

In short, questions remain about the effectiveness How do the processes listed in Table 1 affect re-

of the FITD procedure, the conditions under which it sponses to an FITD manipulation? First, the proce-

will be found, and how to explain successful demon- dures used to initiate and carry out the FITD technique

strations of the effect. We hope to expand on the ear- have the potential to set several psychological pro-

lier FlTD reviews in three ways. First, we begin by cesses in motion. As shown in Table 1, some of these

identifying several processes that potentially come processes increase the likelihood that the request recip-

into play in an FlTD situation. This approach leads to ient win agree to the target request. However, others

several predictions that can be tested by examining are likely to decrease the chance that the individual

relevant conditions in past FITD studies. Thus, we will comply with the second request. Although we use

look at the effect of several variables left unexamined the processes listed in the table to account for findings

in earlier reviews. Second, we are more exclusive from most existing FITD studies, we do not presume

when selecting studies for the meta-analyses than the list to be exhaustive. That is, other processes may

were some of the earlier reviewers. The term be identified in future research.

foot-in-the-door has been used to describe a wide va- Second, the presence and strength of each of these

riety of experimental procedures. For example, some processes will vary depending on the specific proce-

investigators have asked whether the original FITD dures employed to create the FITD manipulation. The

compliance procedures might be expanded to encour- methods employed by researchers to generate the

age people to do something good for themselves FITD effect have been quite varied. Studies investigat-

(e.g., attending a class) or acting altruistically even ing FITD phenomena differ in the amount of time be-

when no request is given (e.g., stopping to pick up tween requests, the relative size of the requests,

dropped papers). Although these are interesting ques- information about other respondents, the type of re-

tions, the findings from these studies may not reflect quest, requester characteristics, whether the same or a

the same underlying processes at work in the type of

situation studied in the original FlTD research. Com-

bining all investigations identified as FlTD studies Table 1. Psychological Processes Affecting Compliance in

the Foot-in-the-Door Situation

potentially clouds the results of the review. Conse-

quently, we employ several criteria for including a Potential Effect on

study in the meta-analyses. Each of these criteria is Psychological Process Foot-in-the-Door

used to eliminate studies and conditions that do not Self-Perception Enhances effect

represent clear applications of the basic FlTD phe- Reciprocity Rules and Reactance Reduces effect

nomenon. Third, it has been about 15 years since the Conformity to Norm Reduces or enhances effect

last published meta-analysis of FITD research. Many Consistency Needs Enhances effect

subsequent investigations provided more relevant Attributions Reduces or enhances effect

Commitment Enhances effect

data on which to base our conclusions.

304

Copyright ©2000. All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/burger-091113232013-phpapp01/85/Burger-2-320.jpg)

![FOOT-IN-THE-DOOR

nation, typically a self-perception process. Inconsis- the initial request. Researchers, salespeople, and the

tent findings have led some researchers to suggest that like will reduce the effectiveness of the procedure and

self-perception theory should be replaced with another may even do more harm than good when they (a) in-

explanation for the FITD effect. In contrast, our analy- form individuals that few people agree to the initial re-

ses found a great deal of evidence to support a quest, (b) use the same person to deliver a second

self-perception explanation. However, we argue that request for a different behavior immediately after the

self-perception is only one process set in motion by an first request, and (c) pay individuals for performing the

FITD manipulation and that many of the inconsistent initial request.

findings in the FITD literature can be understood by Researchers from several different disciplines have

considering the impact of processes in addition to been investigating the effectiveness of and explana-

self-perception. For example, it appears that whatever tions for the FITD procedure for a third of a century.

push self-perception gives toward agreement with the The possibility of increasing sales, donations, recruit-

target request can be overwhelmed by telling the indi- ment, and volunteers with a relatively quick, inexpen-

vidual that few people go along with such requests. sive, and nonthreatening technique has proven

Although our analyses suggest that self-perception irresistibly tantalizing. Yet, as our review and analyses

processes contribute to the effectiveness of the FITD demonstrate, there is more to this simple and

procedure, questions remain about how the process easy-to-use procedure than initially meets the eye.

works. In particular, several researchers have asked

whether the attitude change that takes place during the

self-perception process is for a specific behavior or References

cause or for a more general and far-reaching attitude.

Does the manipulation change, for example, how help- *References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in one

or more of the meta-analyses.

ful the participants believe themselves to be or how

*Allen, C. T., Schewe. C. D., & Wijk, G. (1980). More on

they feel about safe driving? Indeed, this issue has been self-perception theory's foot technique in the pre-calVmail sur-

part of FITD discussions from the outset. Freedman vey setting. Journal of Marketing Research, 17. 498-502.

and Fraser (1966) suggested that either a specific or a American Psychological Association (I 974-present). PsycLlT

general change in attitude might be sufficient to pro- [CD-ROM]. Wellesley Hills. MA: SilverPlatter Information

Services [Producer and Distributor].

duce the FITD effect:

Asch, S. E. (1951). Effects of group pressure upon the modification

and distortion of judgments. In H. Guetzkow (Ed.), Groups,

The change in attitude could be toward any aspect of leadership, and men (pp. 177-190). Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie.

the situation or toward the whole business of saying Baer, R., & Goldman, M. (1978). Compliance as a function of prior

"yes." The basic idea is that the change in attitude need compliance, familiarization, effort and benefits: The

not be toward any particular issue or person or activity, foot-in-the-door technique extended. Psychological Reports,

but may be toward activity or compliance in general. 43, 887-893.

(p.201) Batson, C. D., Harris, A c., McCaul, K. D., Davis, M., & Schmidt, T.

(1979). Compassion or compliance: Alternative dispositional

One suggestion worthy of further investigation is that attributions for one's helping behavior. Social Psychology

Quarterly, 42, 405-409.

the FITD effect is enhanced to the extent that both a Beaman, A. L., Cole, C. M., Preston, M., Kientz, B., & Steblay, N. M.

general and a specific change in attitude occurs. If the (1983). Fifteen years of foot-in-the-door research: A

two requests resemble one another (e.g., support the meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 9,

same cause or require the same action), then both the 181-196.

general and specific attitude will affect the decision to *Beaman, A L., Steblay, N. M., Preston, M., & Kientz, B. (1988).

Compliance as a function of elapsed time between first and sec-

comply with the second request. This analysis is sup-

ond requests. Journal of Social Psychology, 128, 233-243.

ported by the research described earlier that found a *Bell, R. A, Cholerton, M., Fraczek, G. S. R., & Smith, B. A (1994).

stronger FITD effect when the two tasks were similar. Encouraging donations to charity: A field study of competing

Finally, some obvious practical implications can be and complementary factors in tactic sequencing. Western Jour-

drawn from our analyses. The data patterns we uncov- nal of Communication, 58, 98-115.

Bern, D. 1. (1972). Self-perception theory. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Ad·

ered provide guidelines for designing the most effec-

vances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 6, pp. 1-62).

tive FITD manipulation. Researchers, salespeople, New York: Academic.

recruiters and others are most likely to increase com- Berkowitz, L. (1972). Social norms, feelings, and other factors af-

pliance with the FITD technique when they (a) allow fecting helping and altruism. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in

individuals to perform the initial request, (b) overtly la- experimental social psychology (Vol. 6, pp. 63-108). New

York: Academic.

bel the person as helpful or as a supporter of these

Berkowitz, L., & Devine, P. G. (1989). Research traditions, analysis,

kinds of causes, (c) require more than a minimal and synthesis in social psychological theories: The case of dis-

amount of effort to perform the initial request, and (d) sonance theory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 15,

make the target request essentially a continuation of 493-507.

323

Copyright ©2000. All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/burger-091113232013-phpapp01/85/Burger-21-320.jpg)