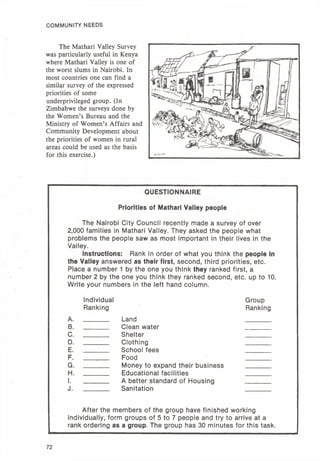

This chapter introduces the purpose and methodology of the book. It aims to provide community workers with skills for building a new, just society through a participatory training method. This method is informed by five key influences: Paulo Freire's work on critical consciousness, human relations training, organizational development principles, social analysis, and Christian concepts of transformation. The goal is to promote coherence between the content covered and participatory methods used, in order to help liberate people from poverty and oppression and transform society.

![ADULT LEARNING

HOW ADULTS LEARN

The following three pictures help to raise the problems of motivation

of adults and the methods used by adult educators. It helps people examine

their role and approach to adults.

Procedure

a. Explain that you are going

to put a series of posters

on the wall.

b. Put the first one up and

ask the group to describe:

l.

il.

1 1 1 .

What they see

happening in the

picture? (if they are

shy, first give them a

chance to discuss in

2's or 3's.)

When they have

mentioned all the

main points, put up

the second picture and

ask the same question.

Ask them to describe

the two people who

are raising their

hands.

Then put up the third

picture, and again ask

them to describe what

is happening? When

they have identified

that the participants

are dropping out of

class, ask the

following questions.

TUESDAY I. ]

102](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tft-englishbook1-200802123246/85/Book-one-Training-for-Transformation-109-320.jpg)