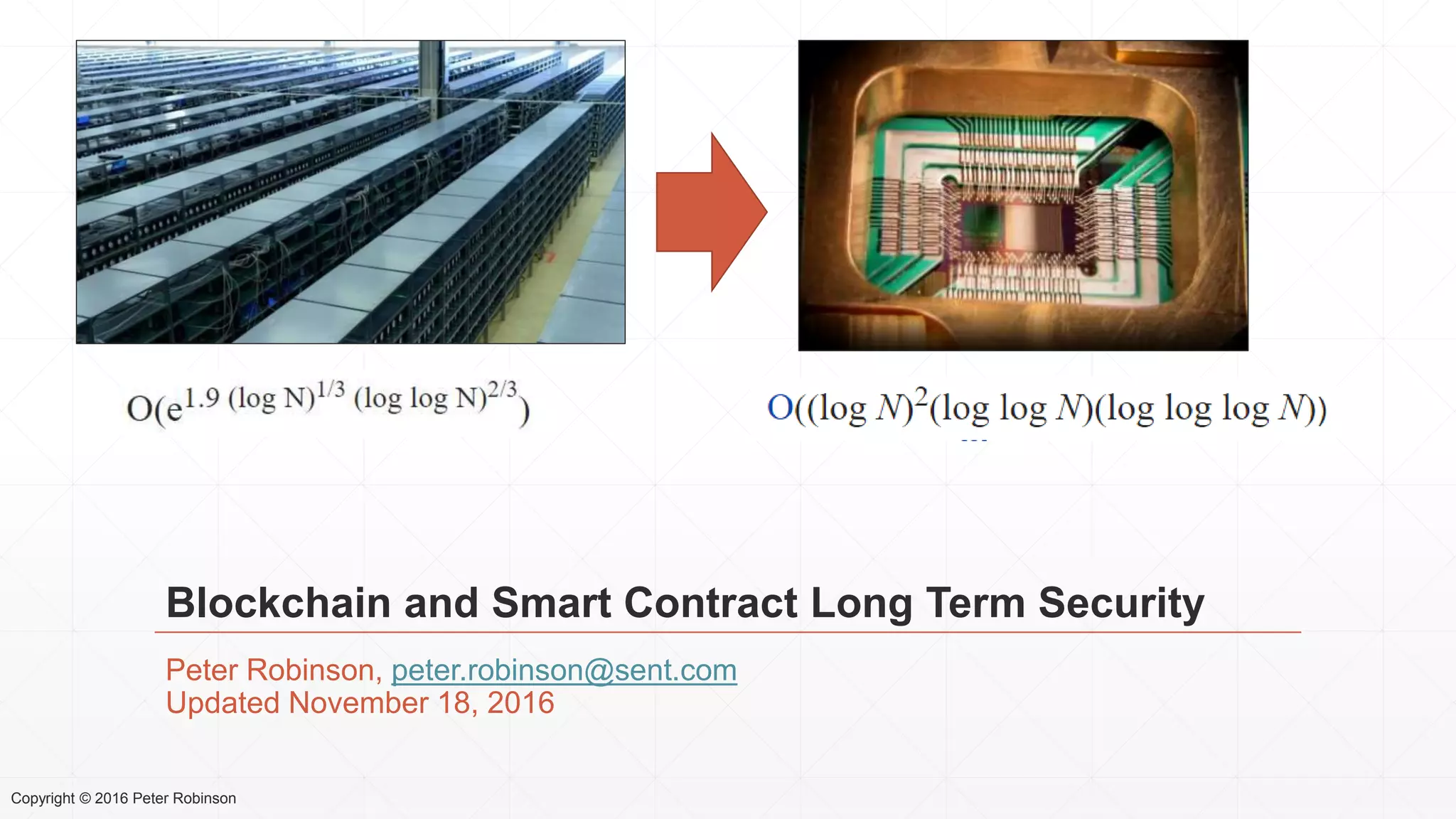

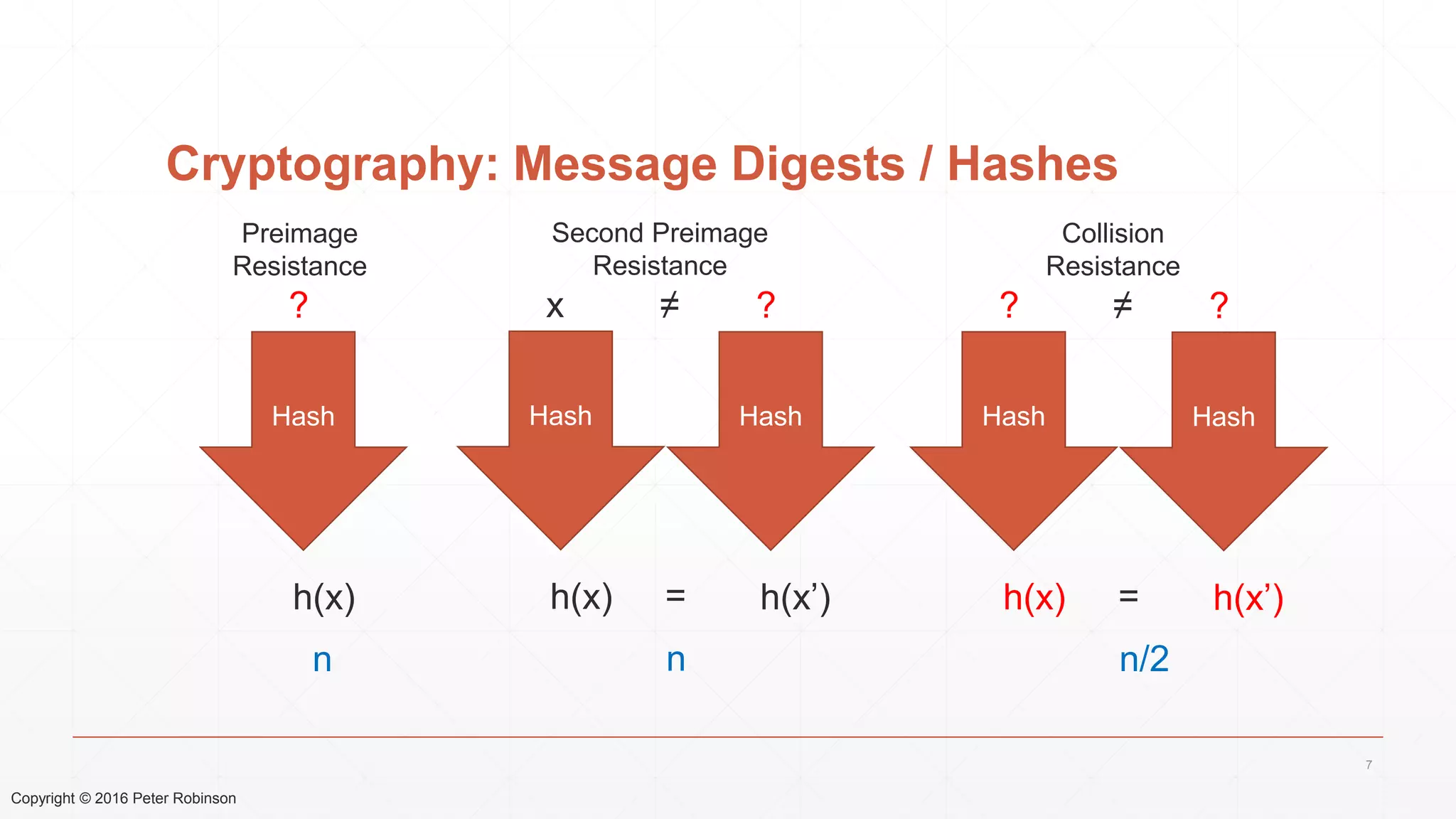

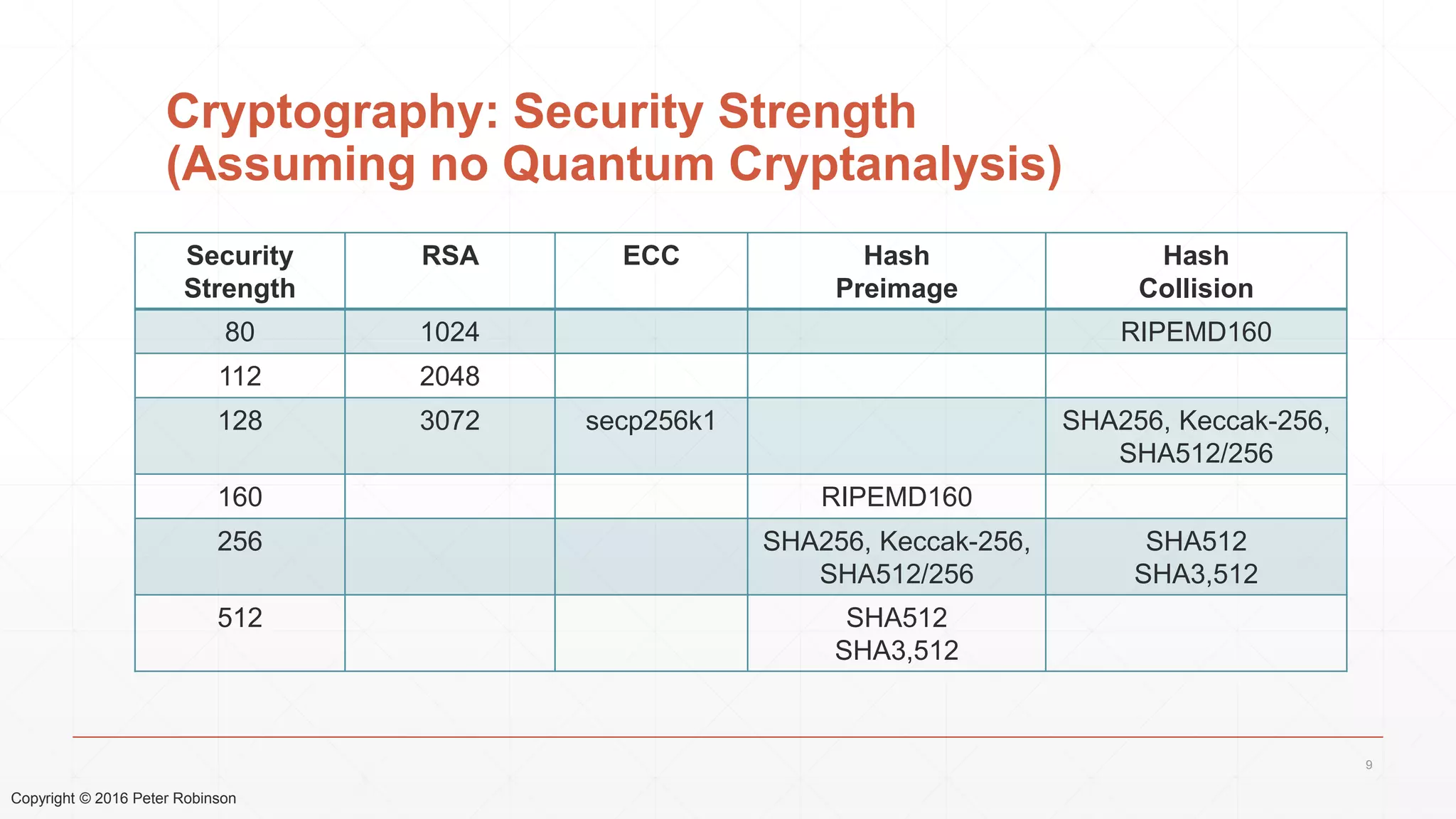

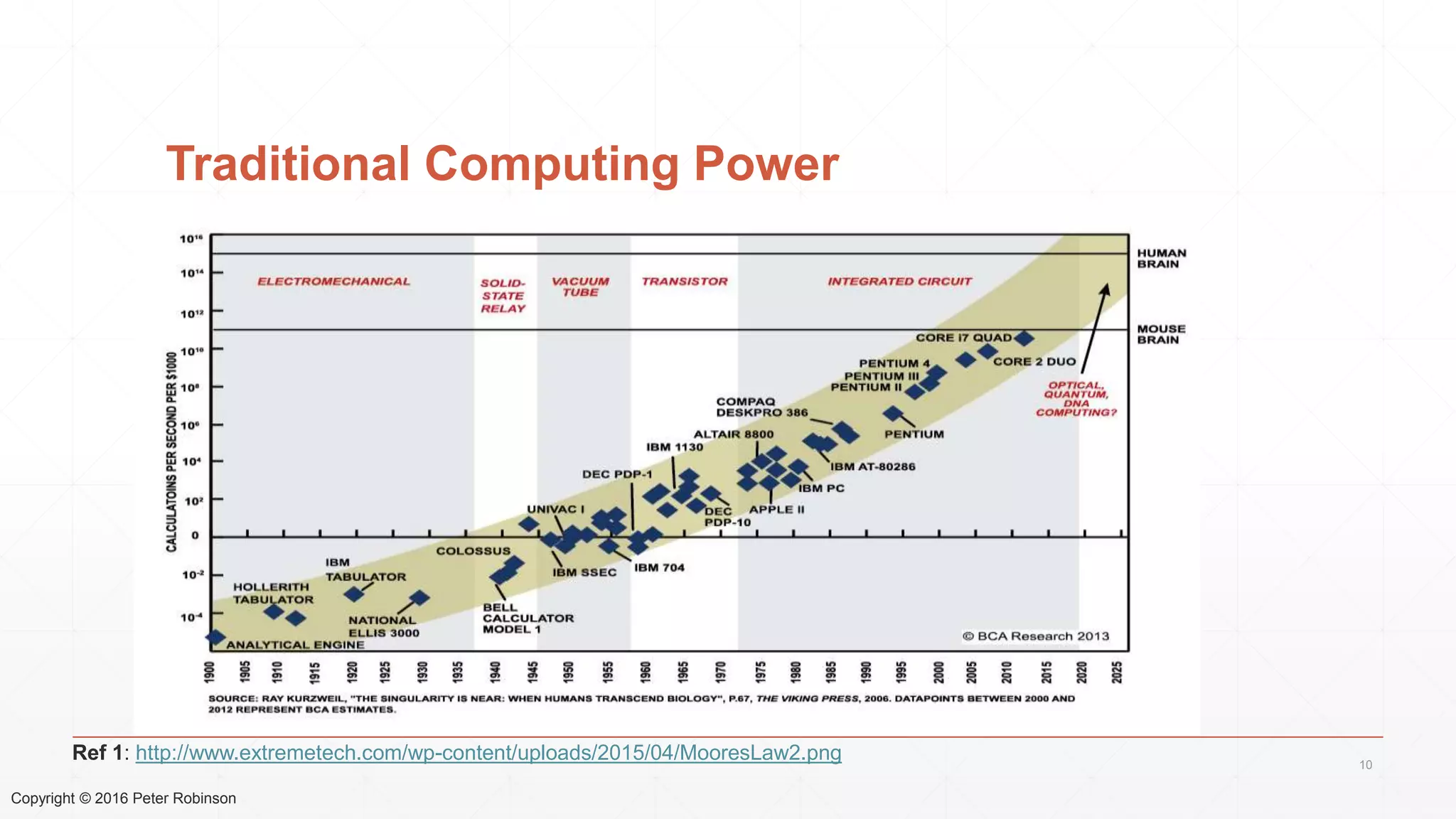

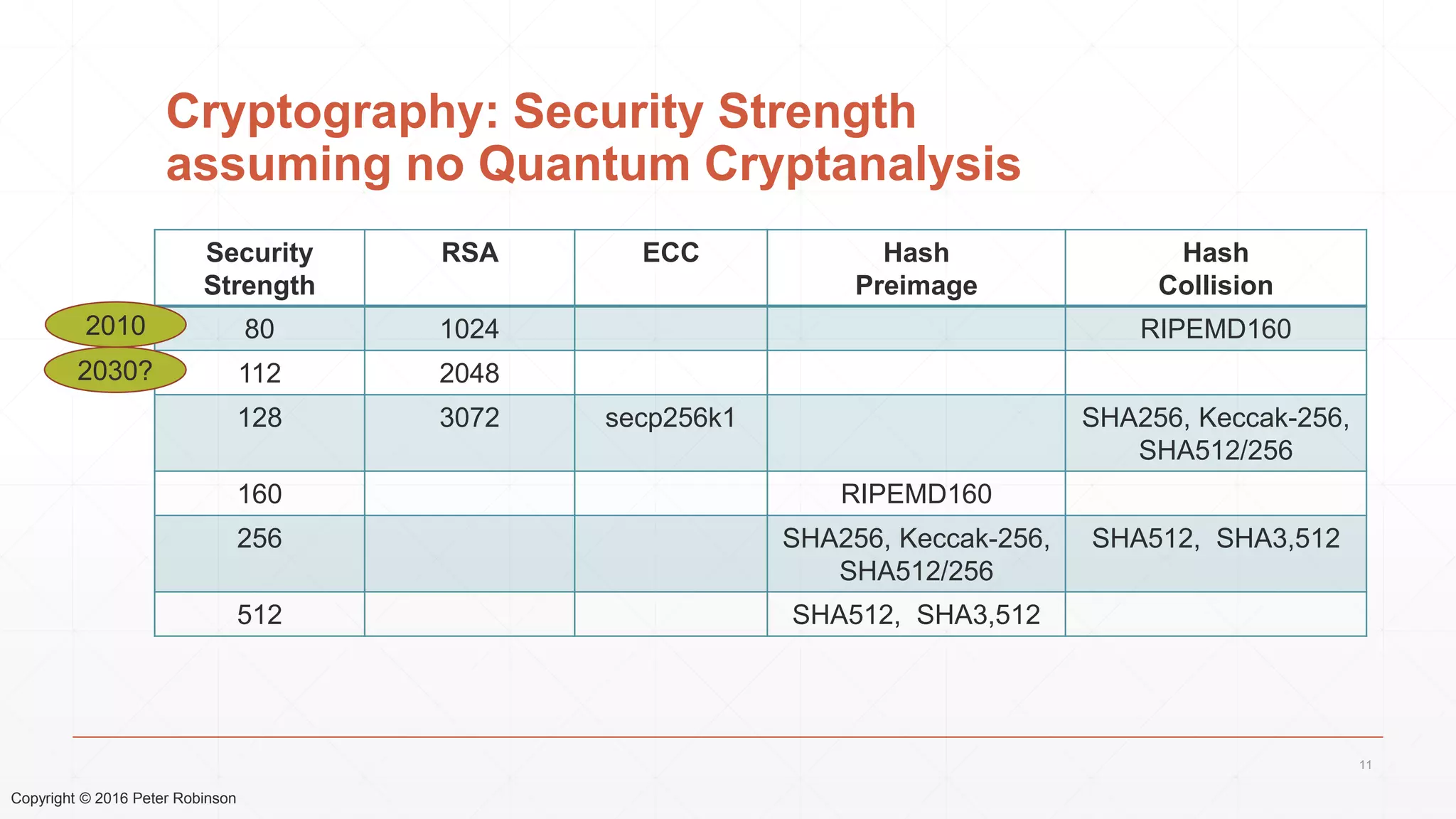

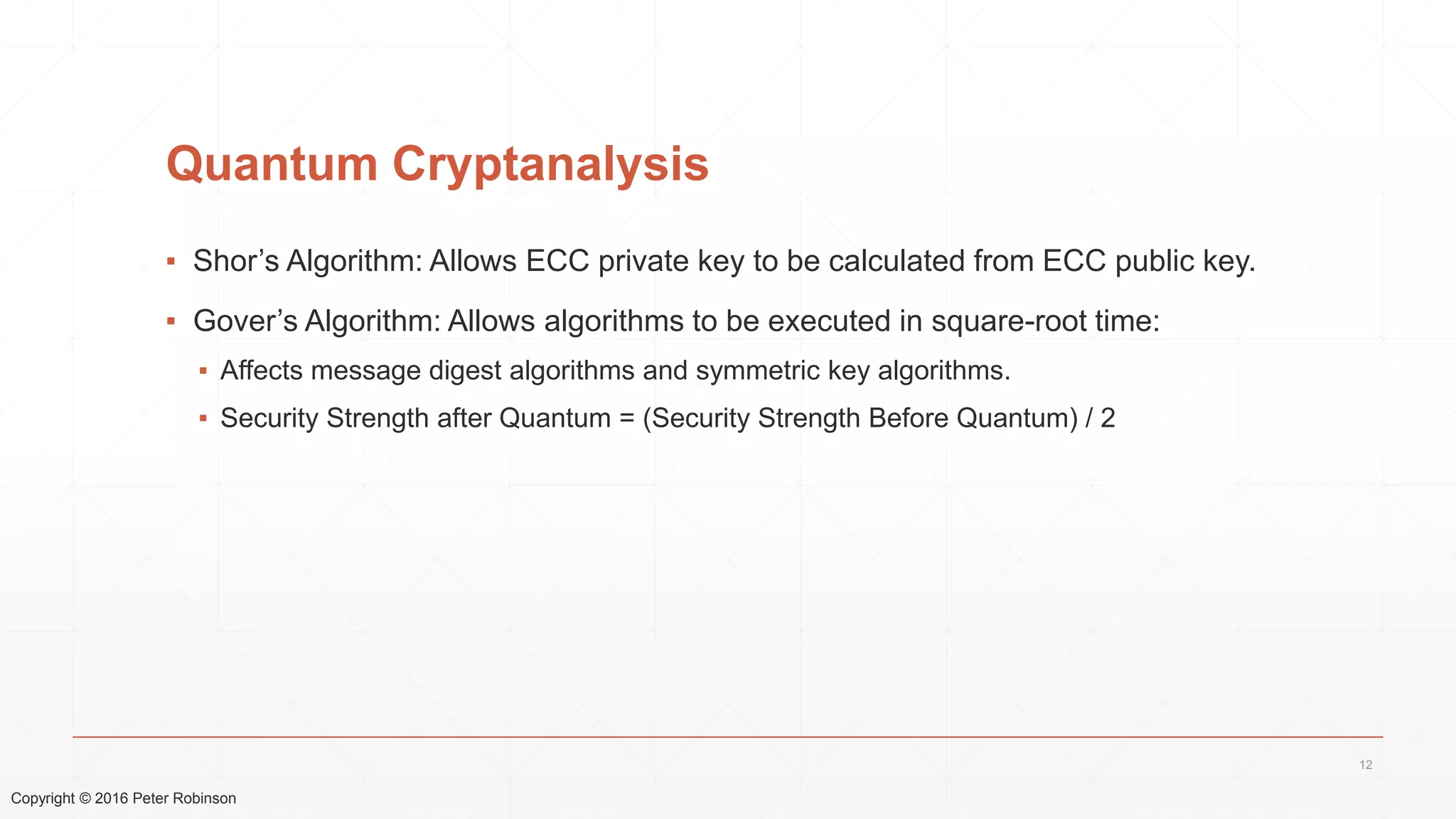

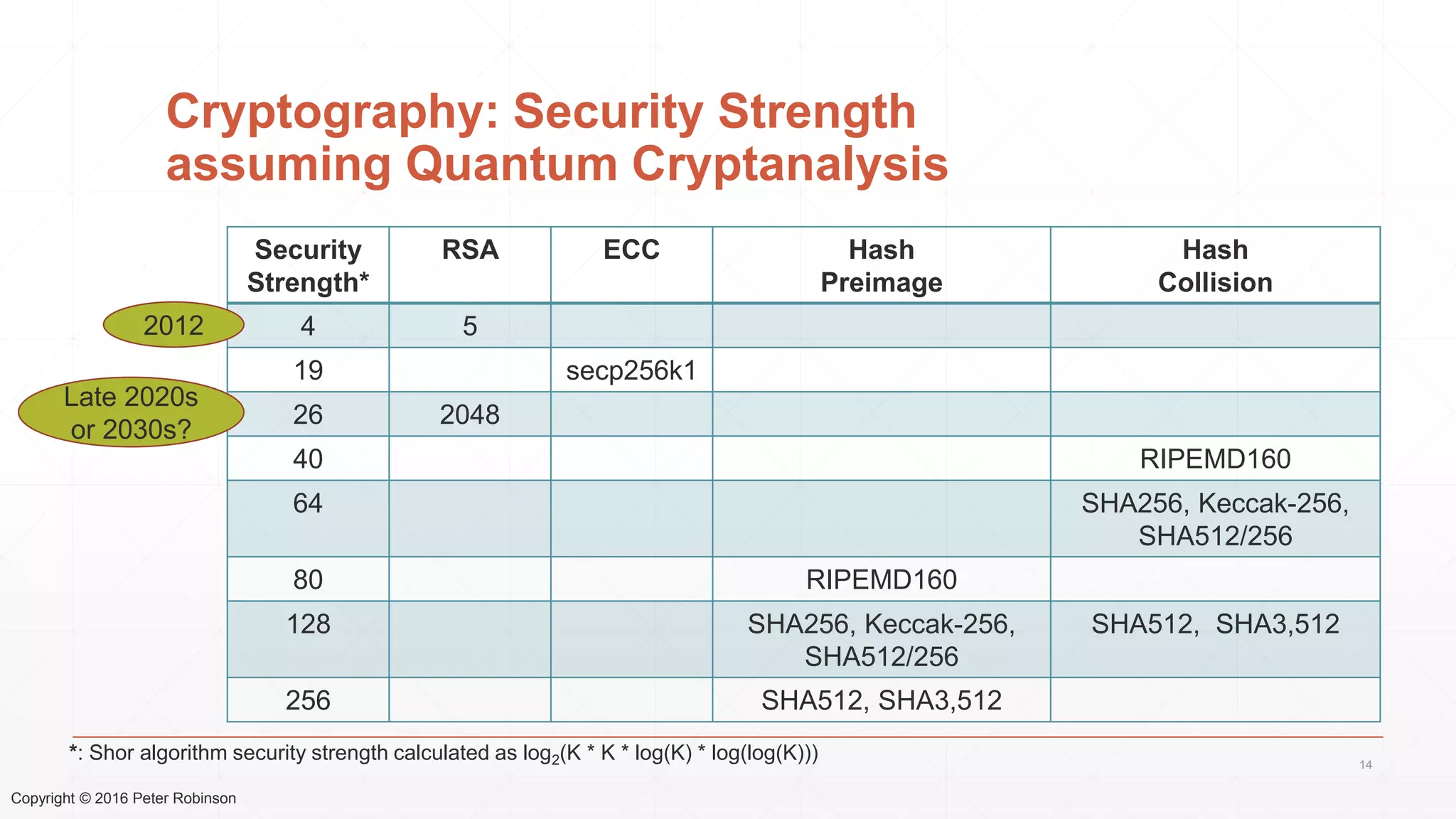

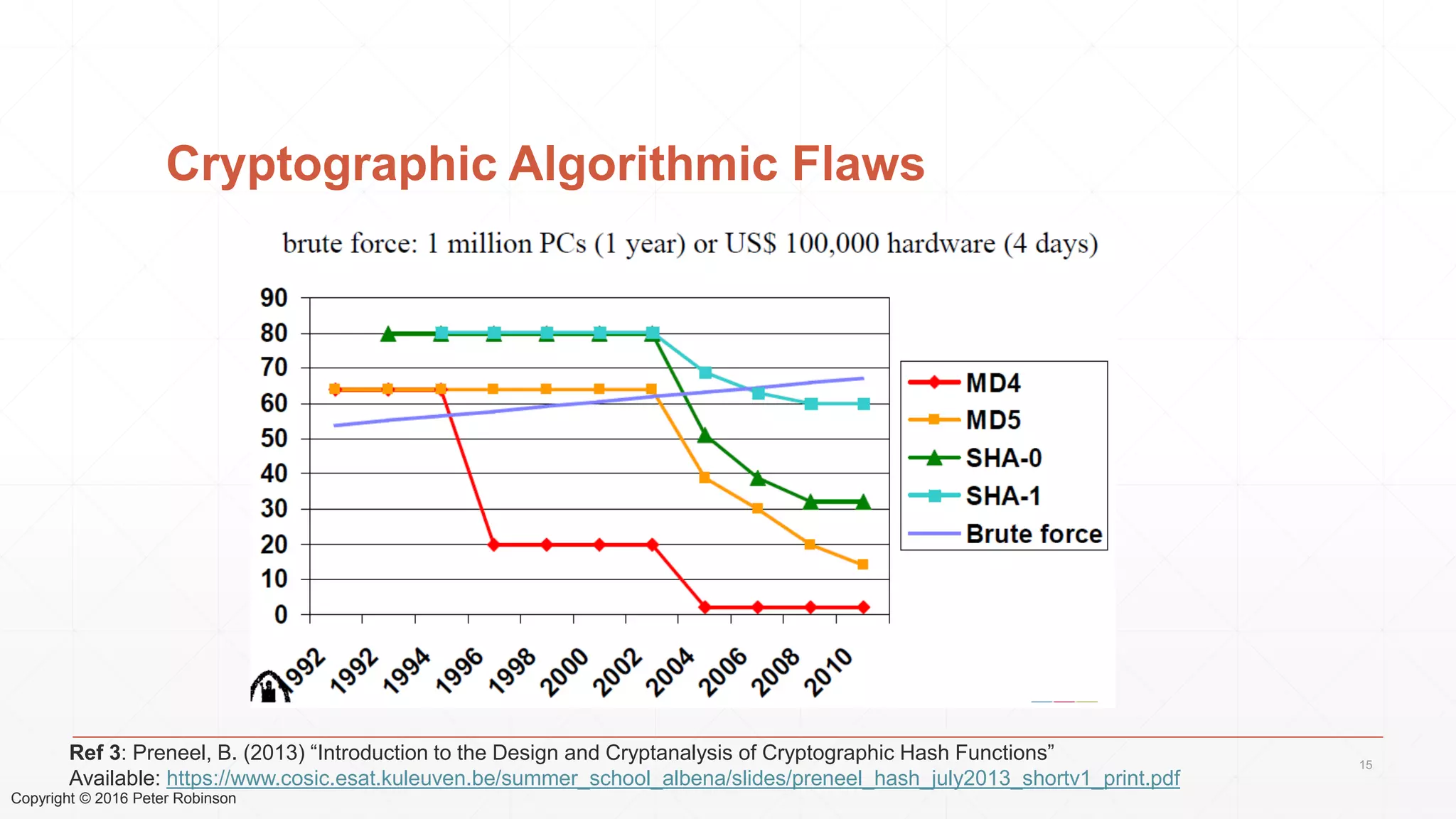

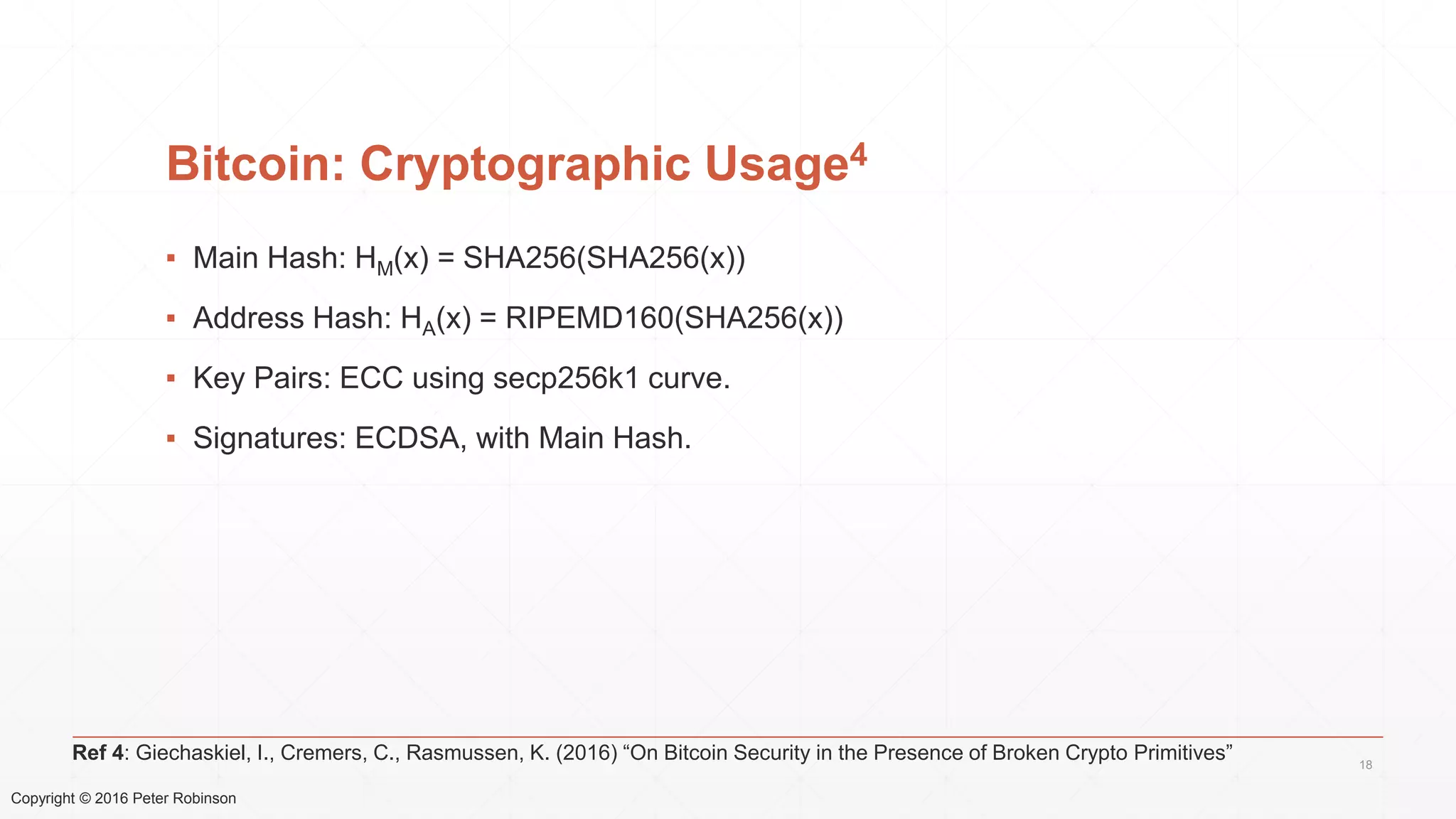

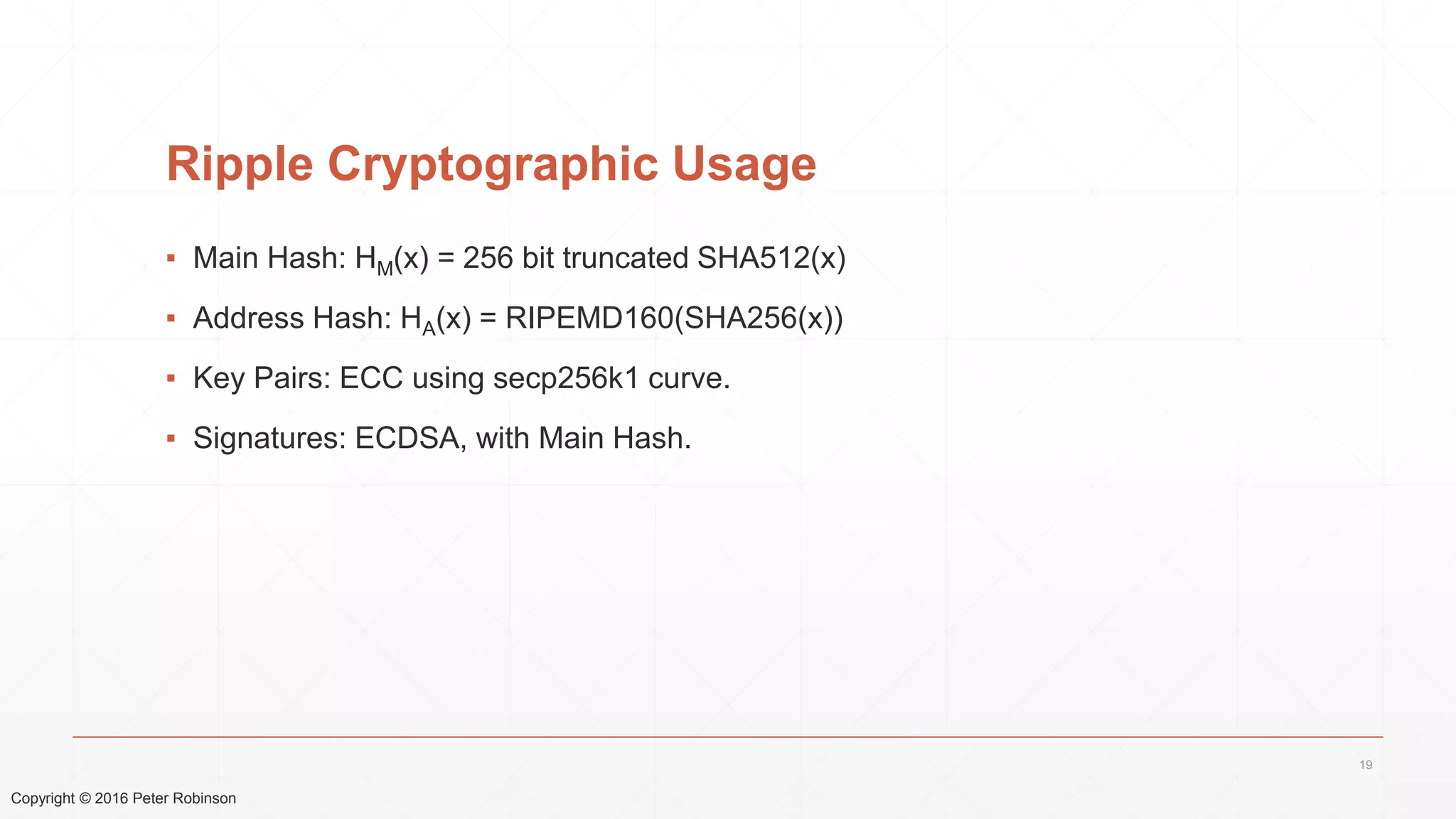

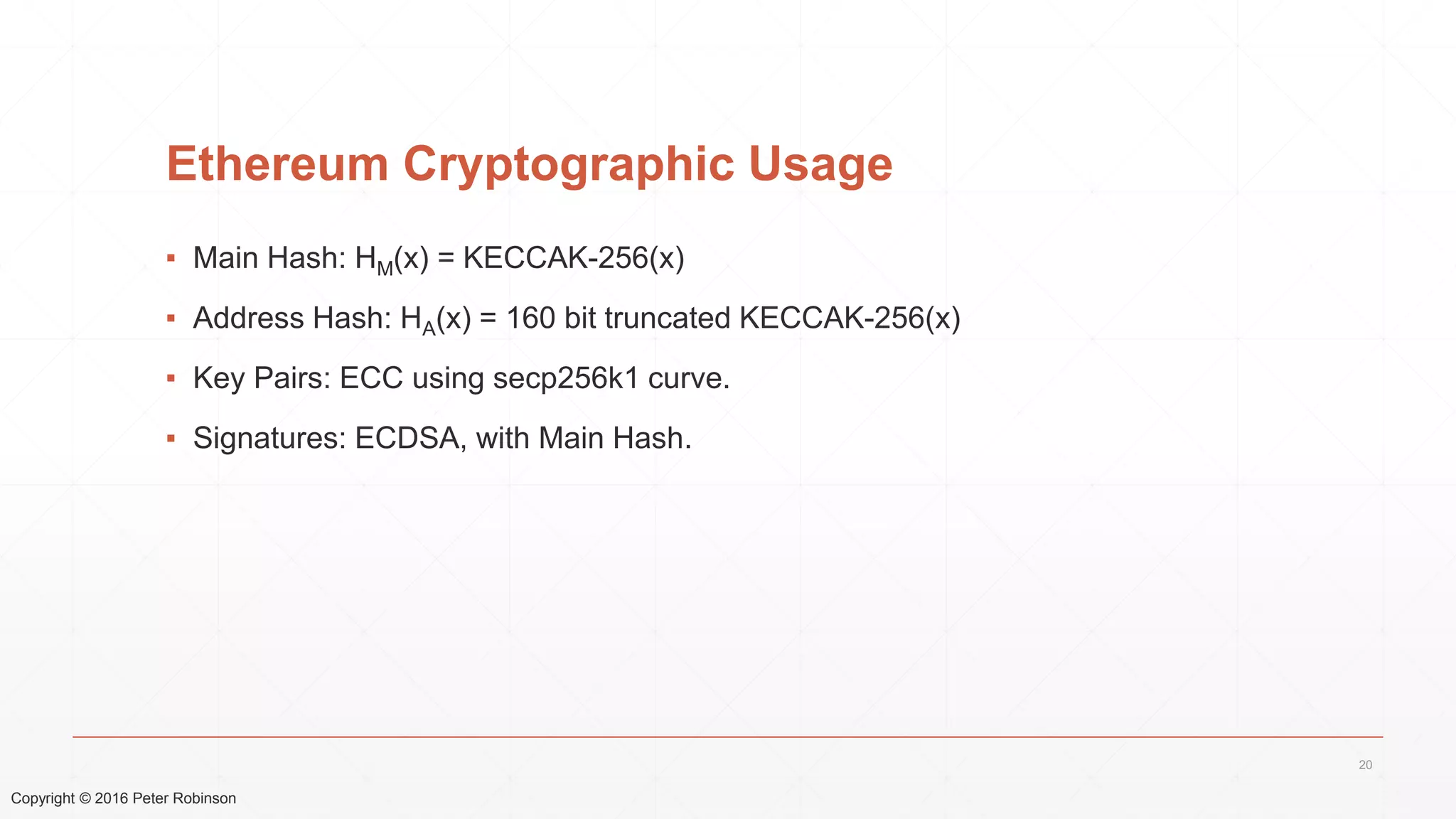

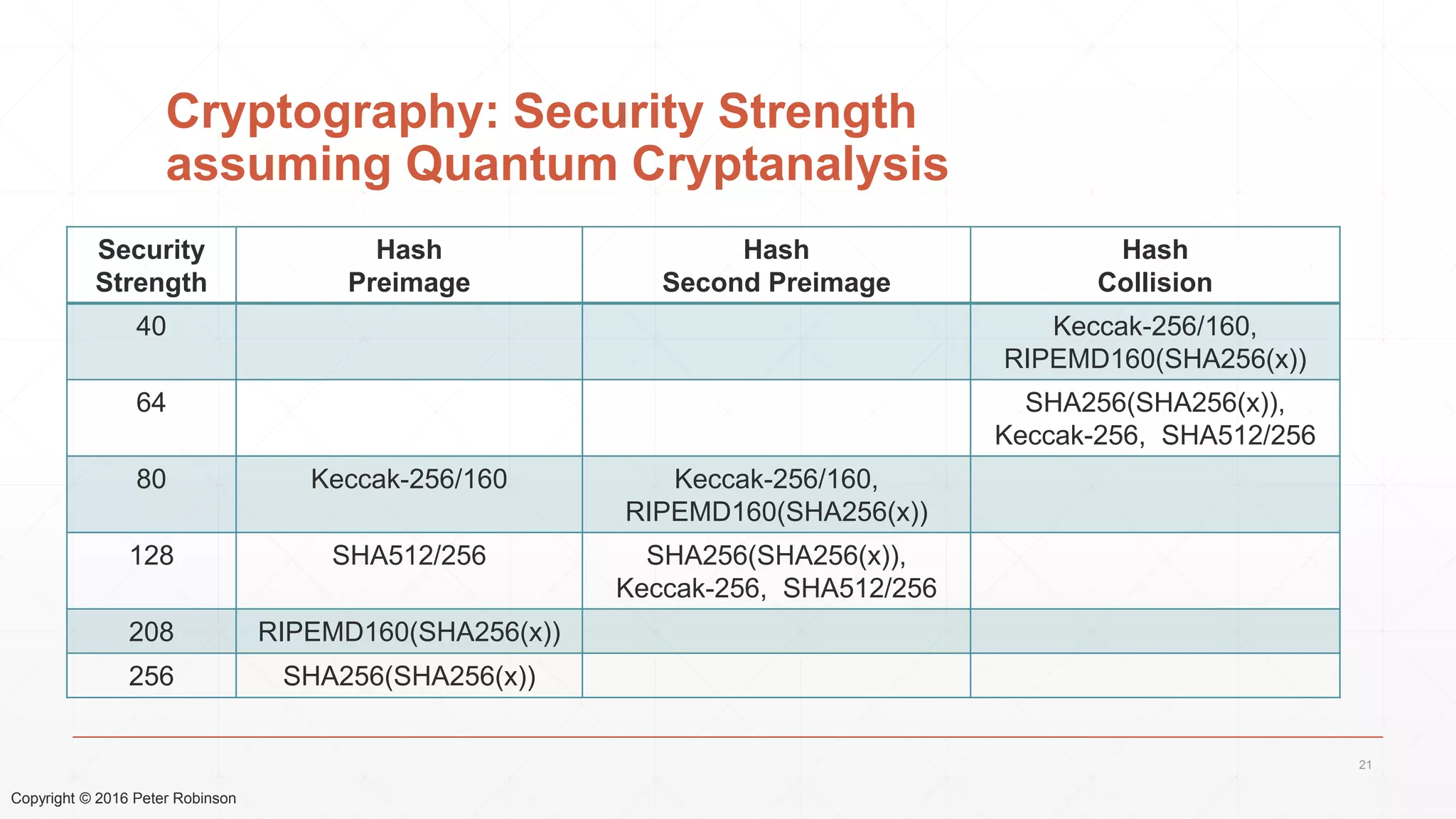

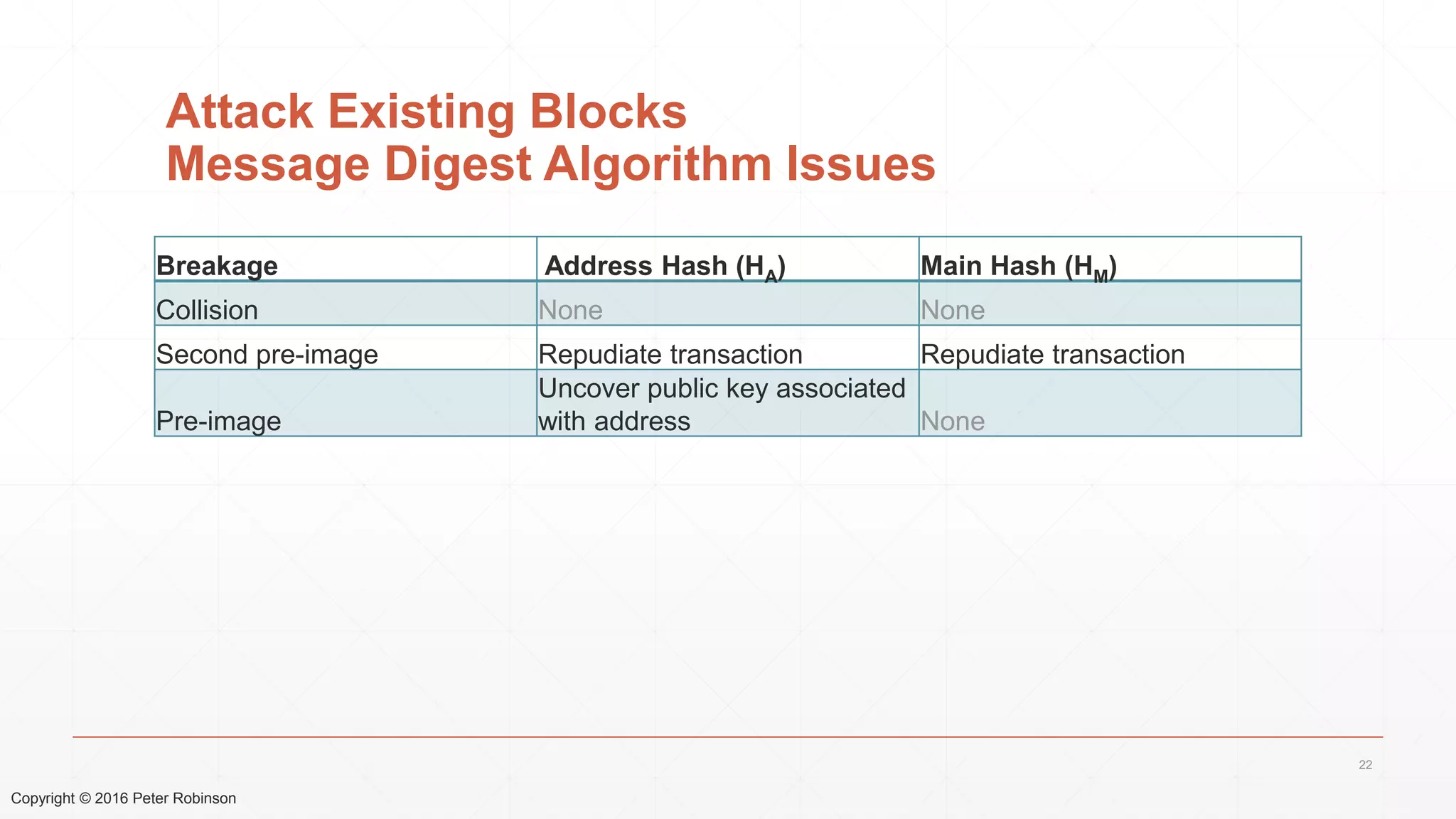

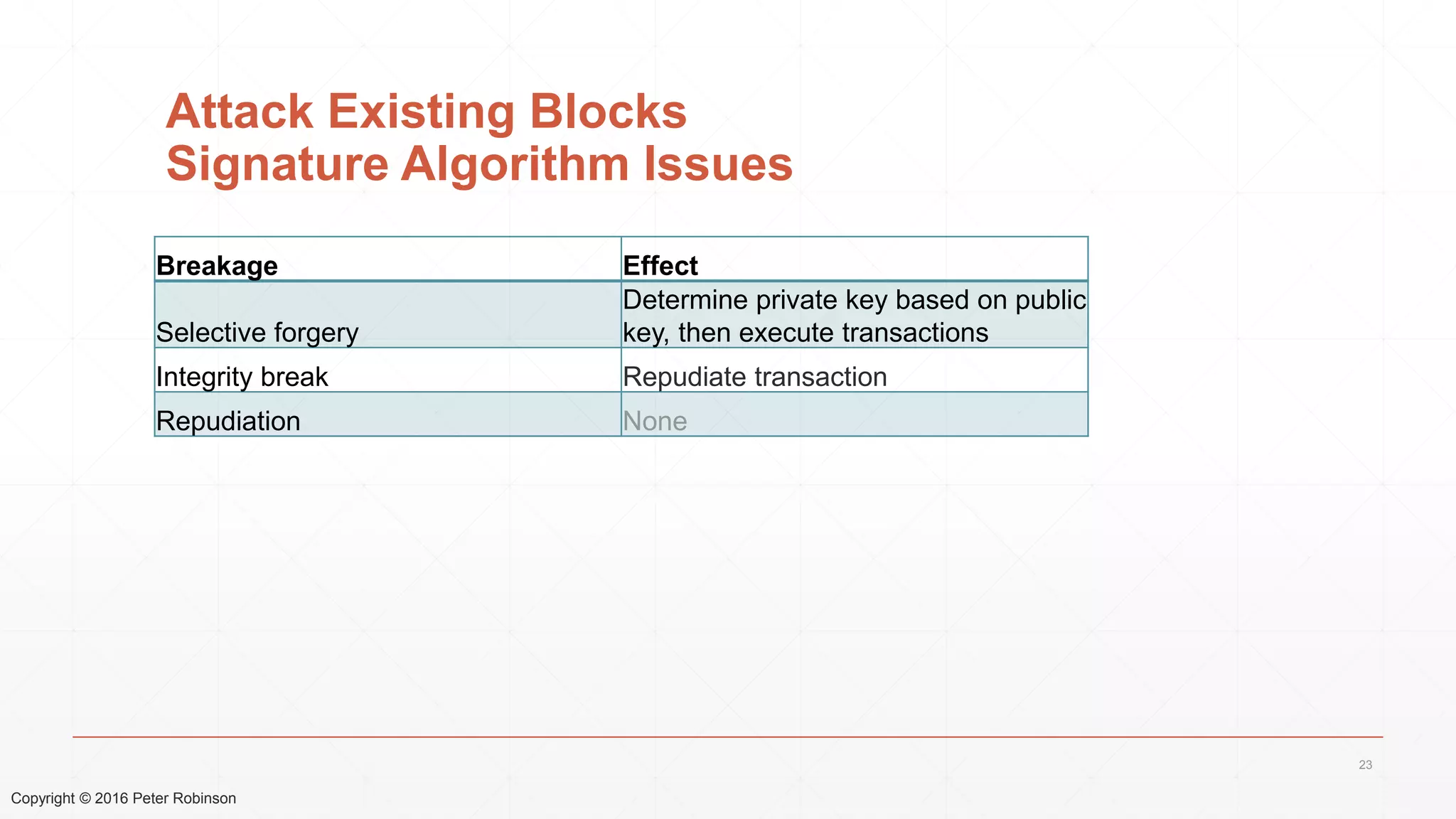

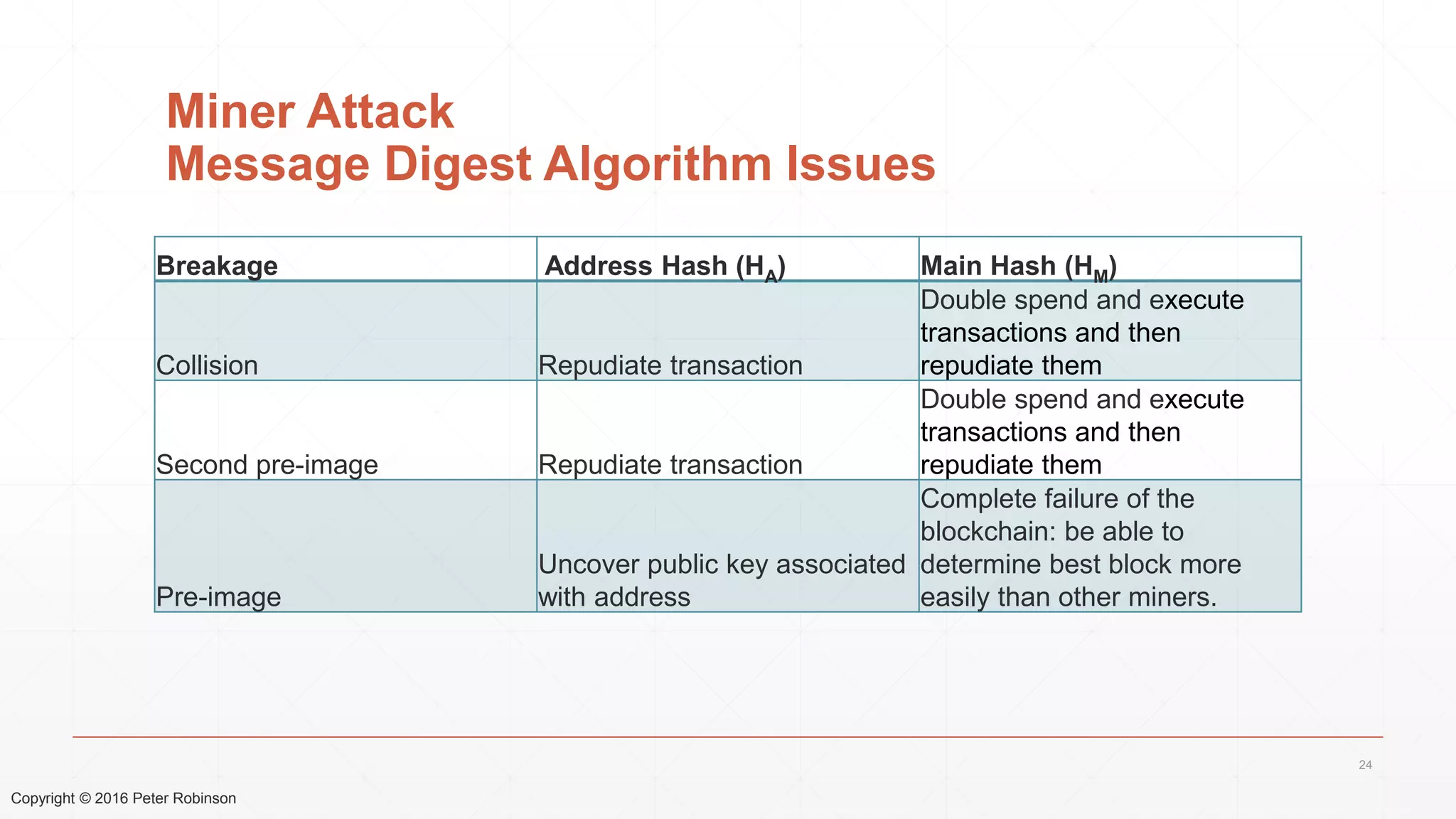

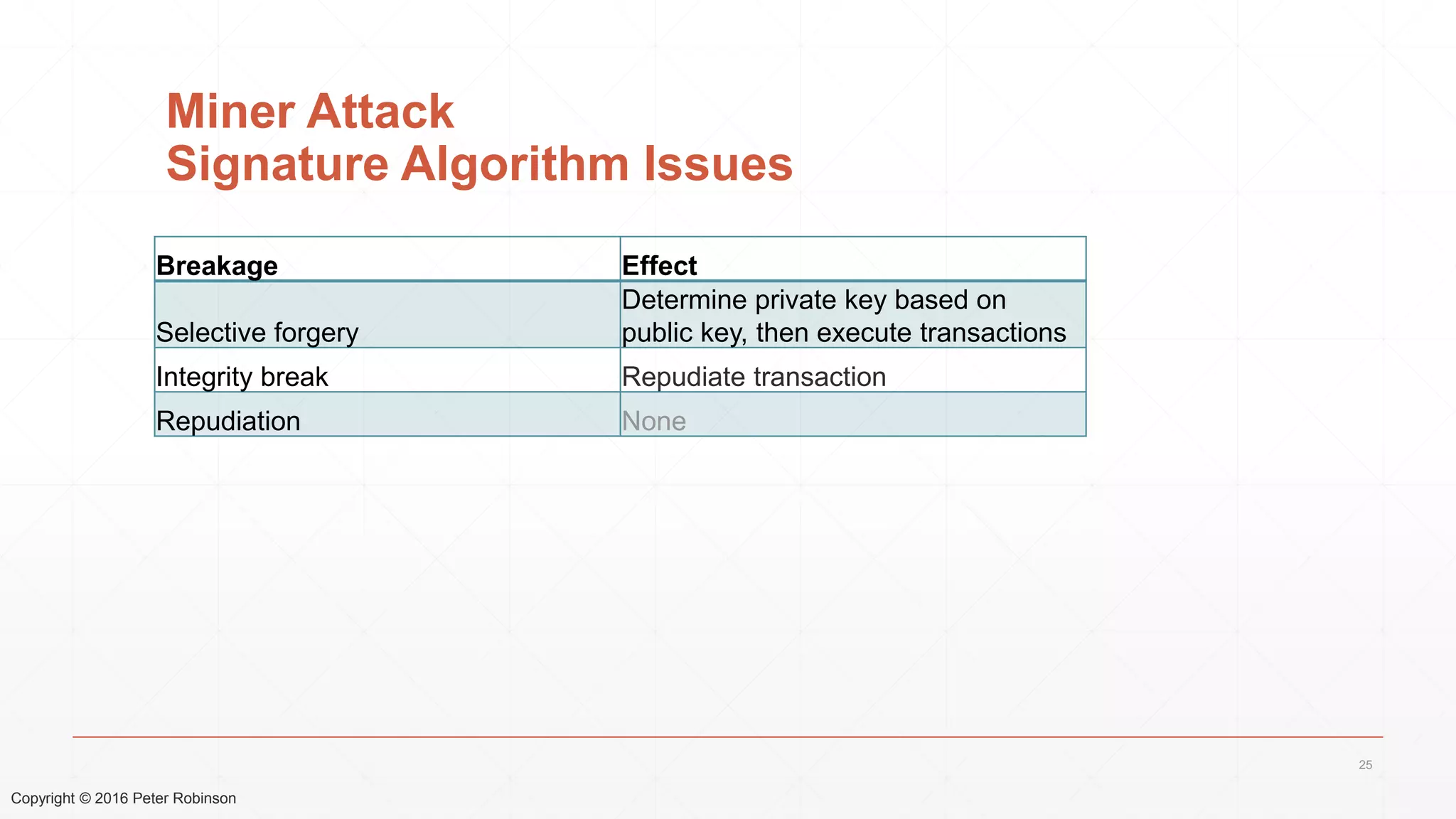

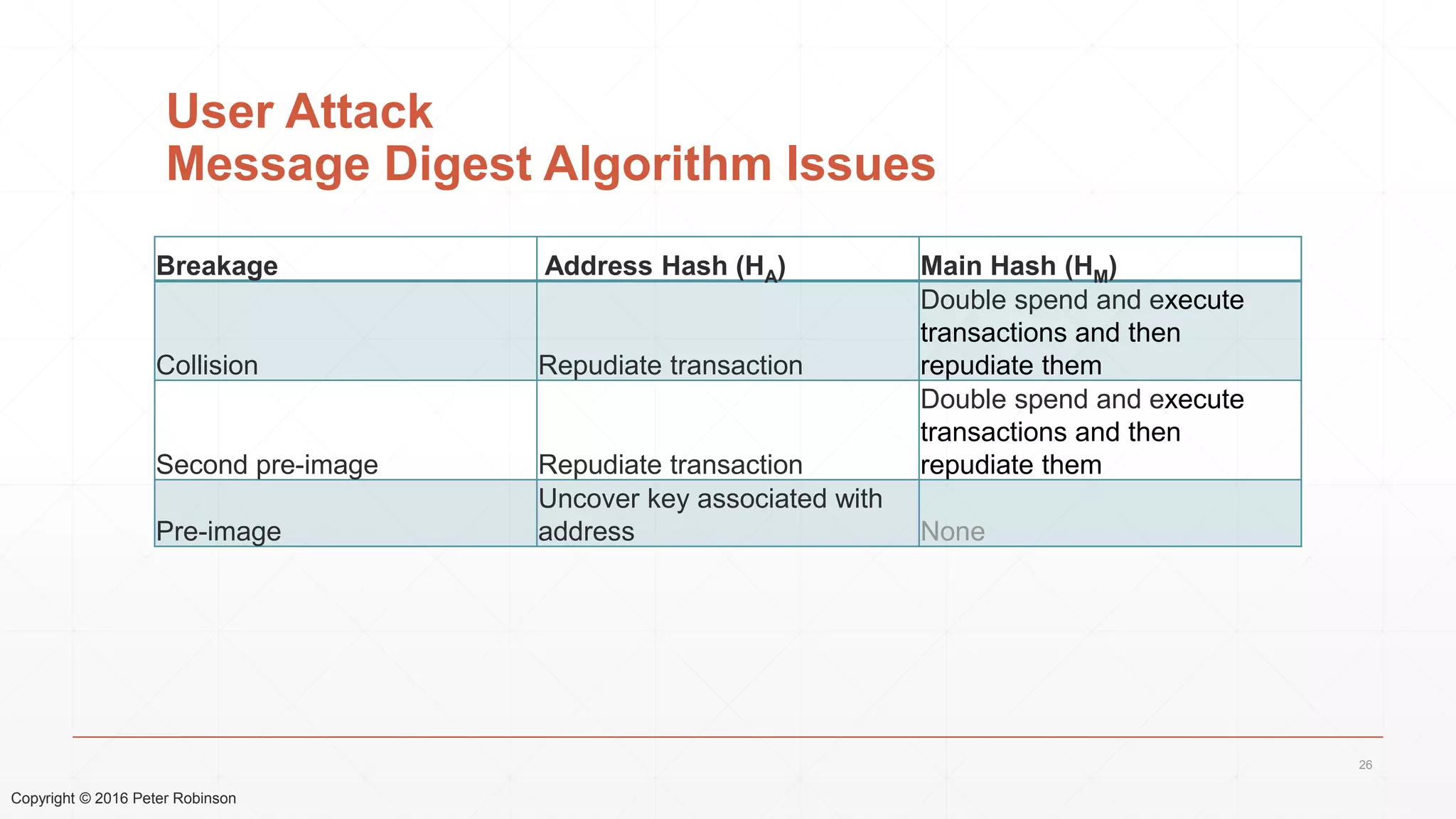

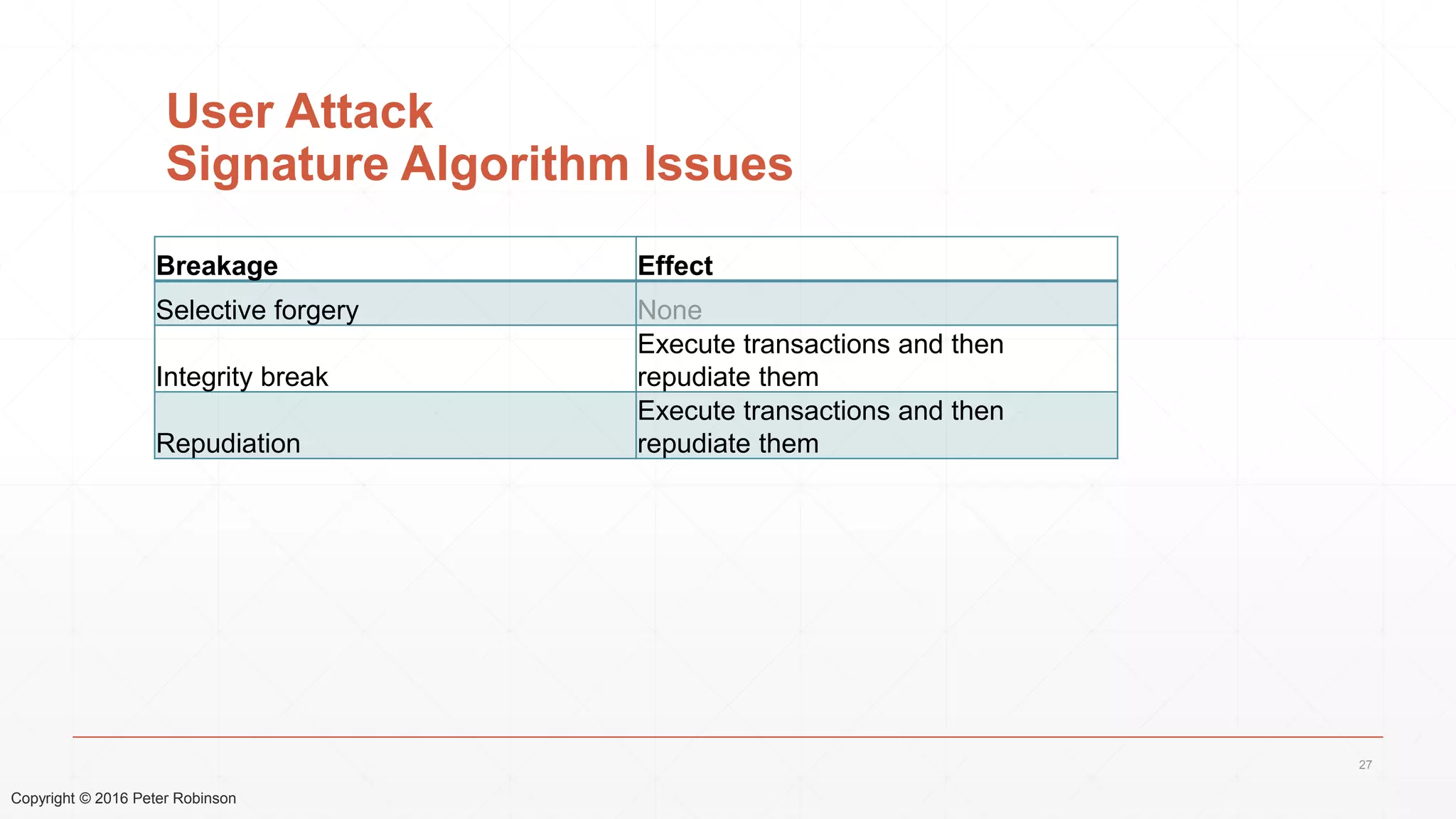

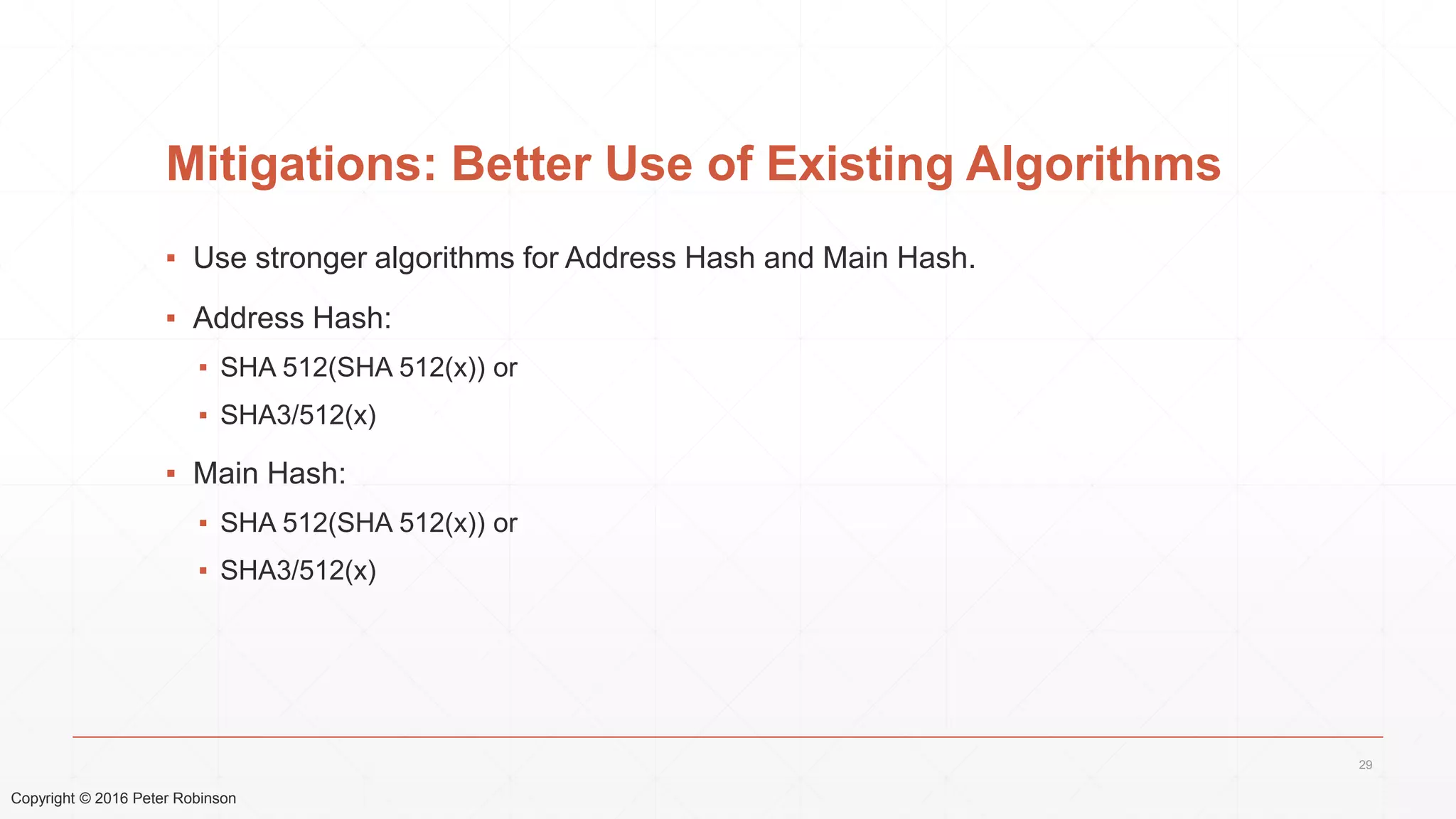

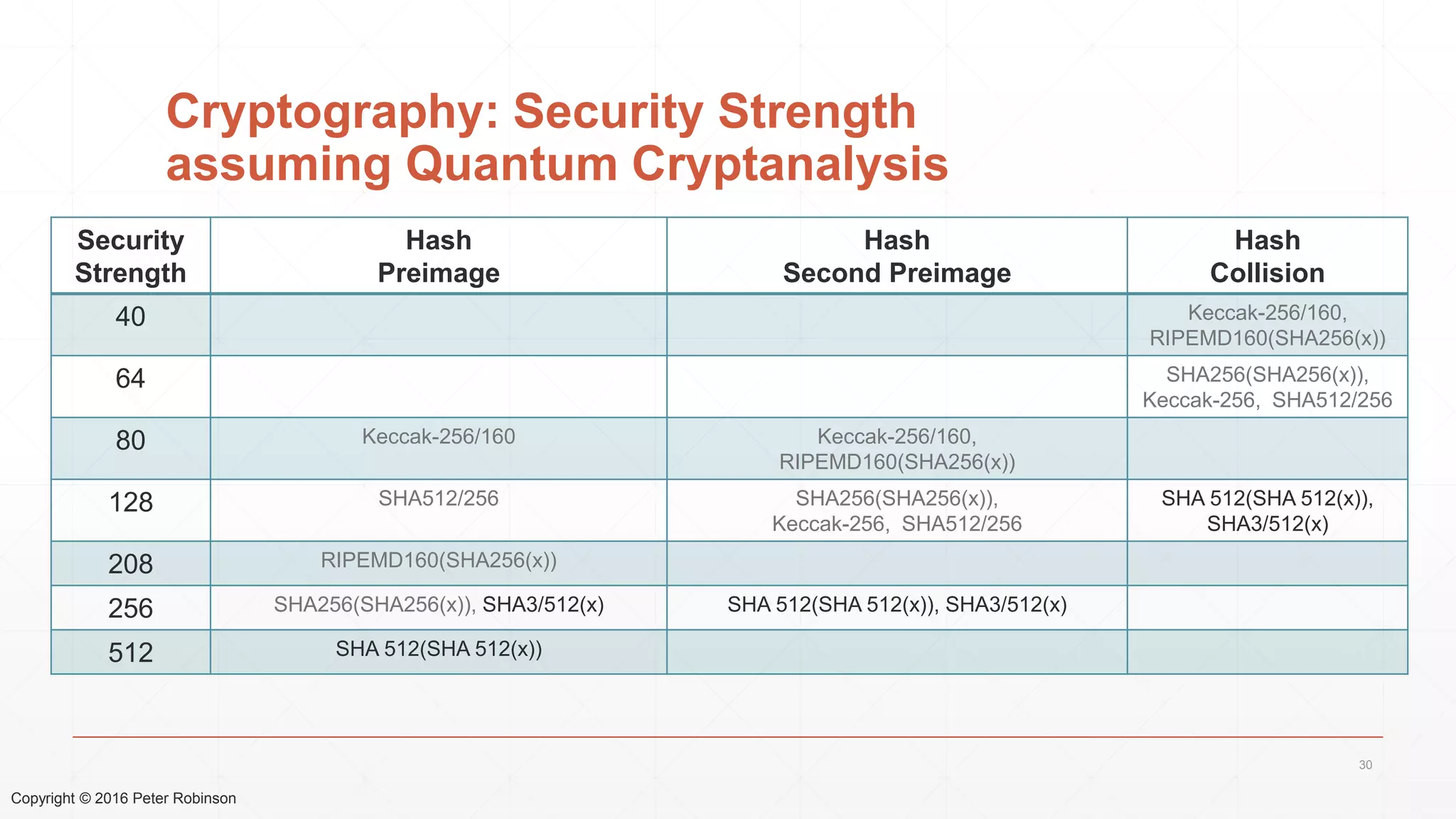

The document presents an analysis of the long-term security of blockchain and smart contract systems, focusing on the challenges posed by increasing computational power, quantum computing, and potential cryptographic flaws. It discusses cryptographic algorithms, their vulnerabilities, and the need for robust mitigation strategies in light of evolving threats. The author emphasizes the necessity for proactive planning and adaptation to ensure the resilience of these systems against future risks.