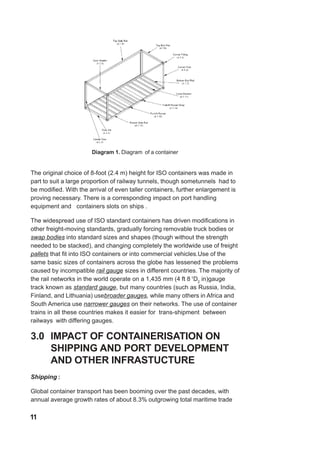

This document provides a history of containerization and the development of multimodal transportation. It discusses how Malcolm McLean pioneered modern container shipping in the 1950s by developing standardized containers that could easily transfer between ships, trains, and trucks. This innovation drove major changes in global trade by reducing shipping costs and handling times. The use of standardized containers led to purpose-built container ships and ports, fueling explosive growth in international commerce and the rise of today's globalized economy. The document also outlines how containerization facilitated focusing production in fewer locations and outsourcing to lower-cost regions, increasing firms' logistical reach around the world.