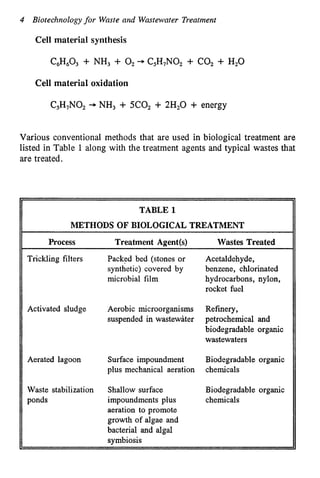

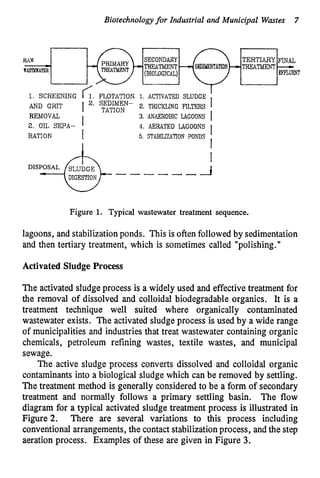

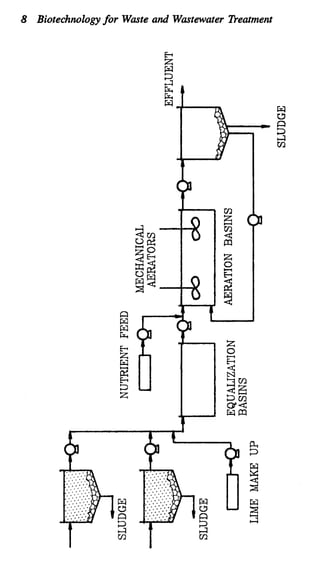

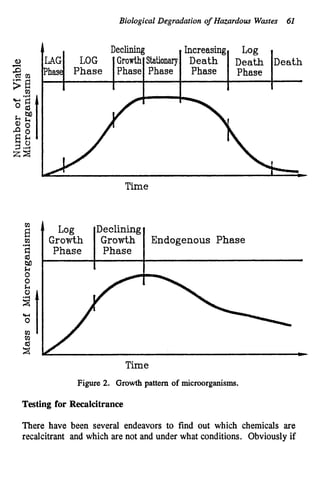

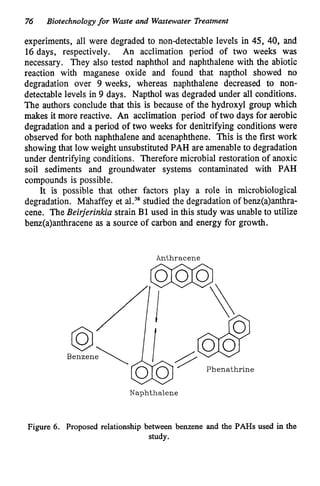

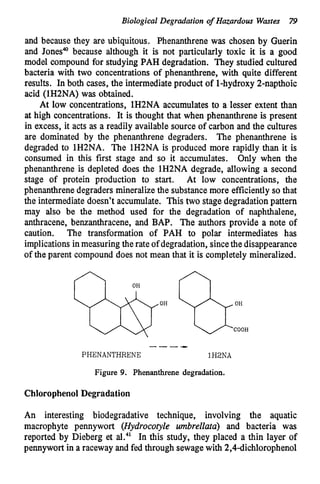

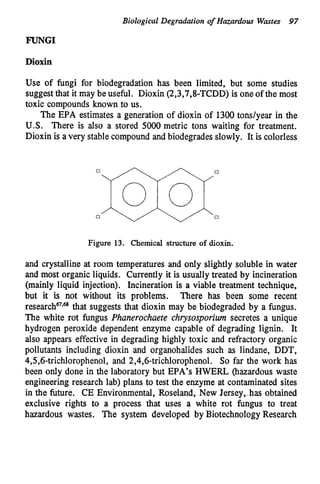

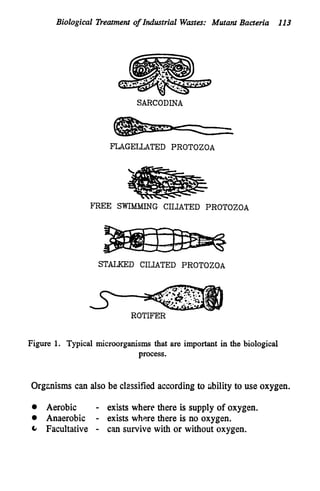

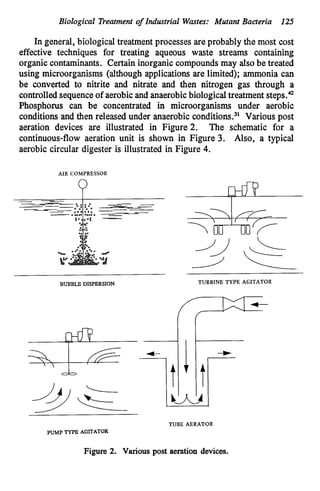

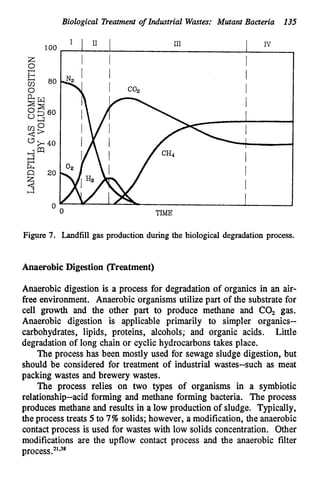

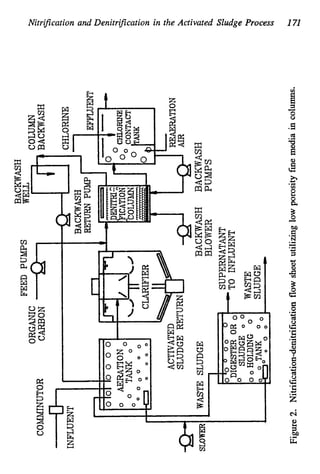

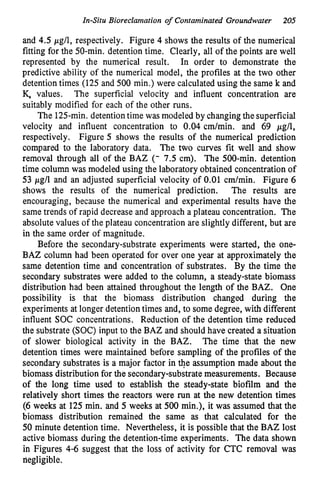

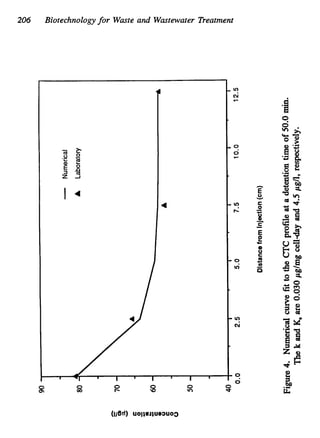

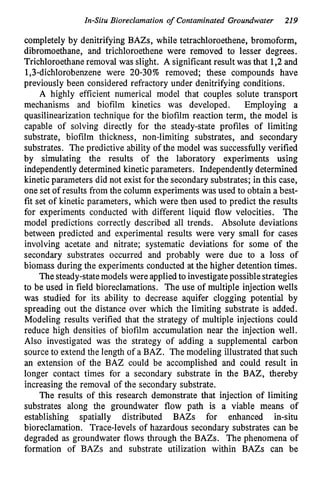

This document discusses various biological treatment techniques for industrial and municipal wastes. It provides examples of recent research using biotechnology to break down pollutants like polychlorinated biphenyls, dioxin, and 2,4-D herbicide. Mutant bacteria formulations are available commercially for treating petroleum refinery wastewater. Biological methods are effective for removing grease from clogged sewers. Overall, microorganisms play a key role in evolving to degrade both natural and man-made compounds through adaptation and new metabolic pathways.