The document explores the interplay between ancient Indian astronomy, scriptures, and mythology, highlighting three distinct phases of astronomical thought: propitiatory, negotiatory, and the current galilean phase, where celestial bodies are studied scientifically. It details the historical roots of astronomy in rituals and the influence of cosmological concepts on human ethics, specifically the notions of time and reincarnation. The treatment of eclipses serves as an example of the integration of scientific understanding with mythological narratives, transforming figures like Rahu and Ketu from demons into astronomical entities within a mathematical framework.

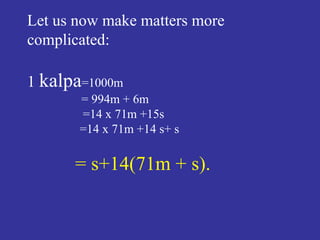

![“Why the factors fourteen and seventy

- one were thus used in making up the

Aeon [kalpa] is not obvious” (Burgess

1860:11). I think this scheme was

constructed working backwards from

the neat round figure of 1000.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/belfastpowerpoint16nov2011-130901090552-phpapp02/85/Scriptures-science-and-mythology-An-ancient-Indian-astronomical-interplay-63-320.jpg)