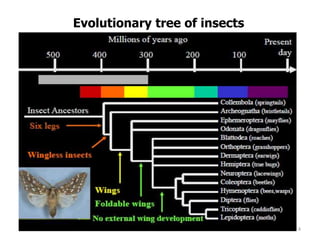

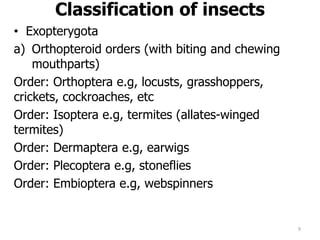

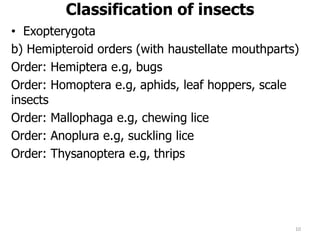

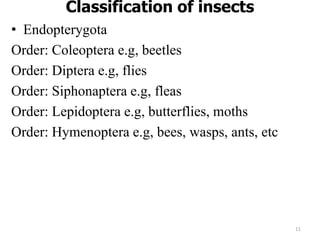

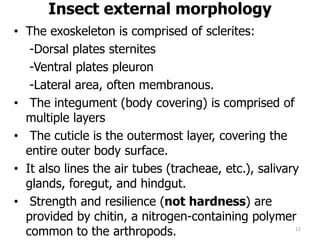

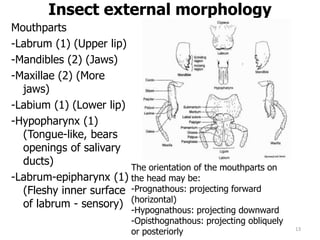

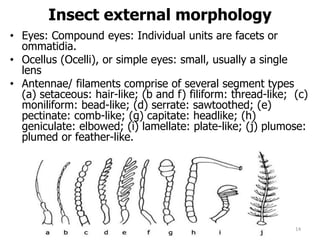

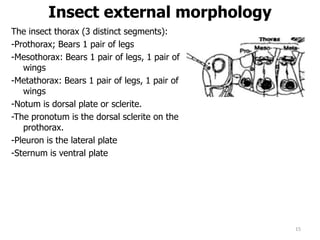

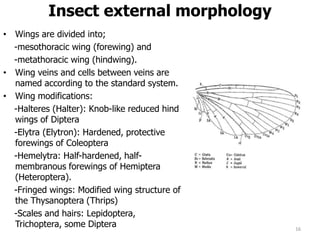

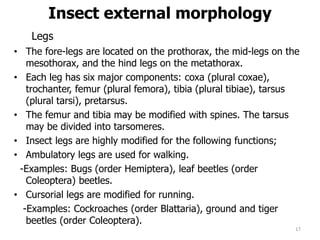

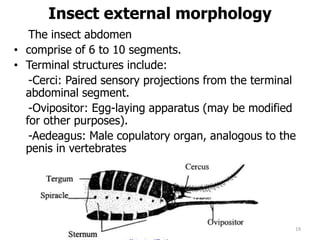

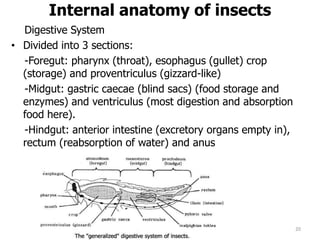

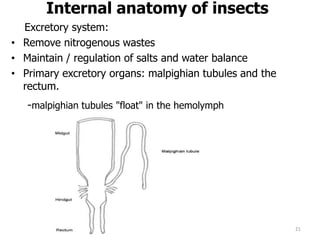

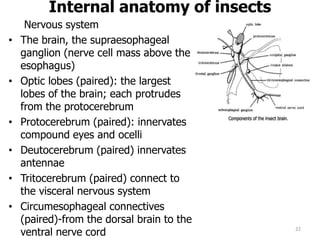

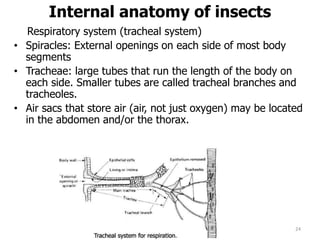

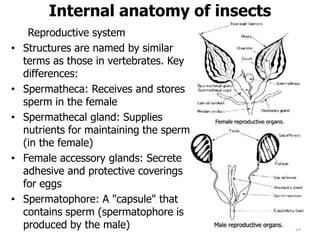

This document provides an overview of basic entomology. It discusses the evolution of insects, their habitats and classification. It describes insect external morphology including body parts, mouthparts, legs and reproductive systems. It also covers internal anatomy focusing on the digestive, excretory, nervous, respiratory and circulatory systems. The document concludes with sections on the economic importance and physiology of insects, specifically their nutrition.