The document discusses the flaws in a safety program developed solely by upper management, emphasizing the importance of employee involvement for its success. Recommendations include dismantling the current program and reconstructing it through a committee of at least 50% employees to better address safety concerns across various departments. It also touches on the issue of workplace behavior and the need for proactive management in dealing with employees' personal issues affecting safety.

![delivery of nursing and healthcare services.

15

Sample Content

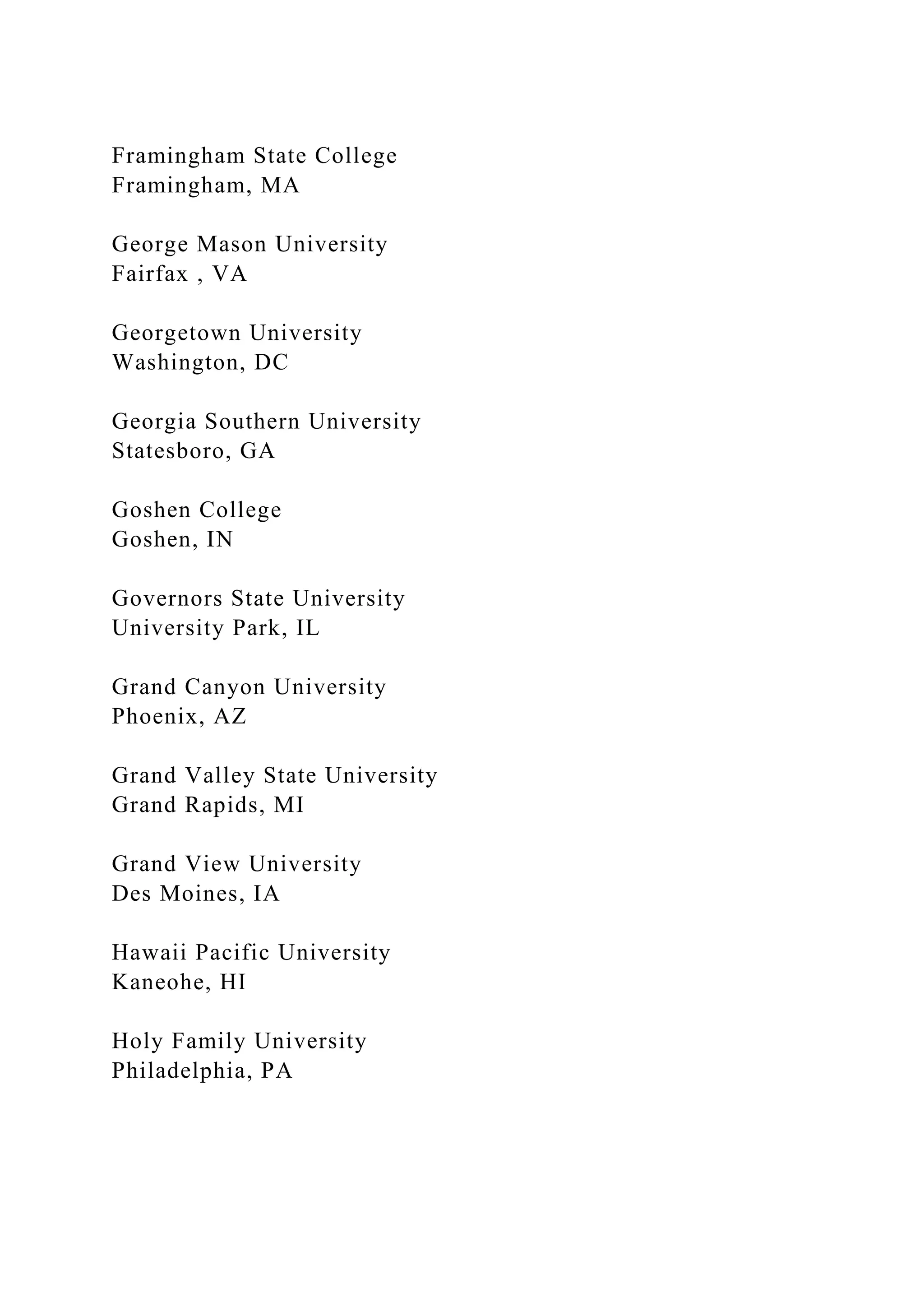

• Quality improvement models differentiating structure, process,

and outcome indicators

• Principles of a just culture and relationship to analyzing errors

• Quality improvement methods and tools: Brainstorming,

Fishbone cause and effect

diagram, flow chart, Plan, Do Study, Act (PDSA), Plan, Do,

Check, Act (PDCA),Find,

Organize, Clarify, Understand, Select-Plan, Do, Check, Act

(FOCUS-PDCA), Six Sigma,

Lean

• High-Reliability Organizations (HROs) / High-reliability

techniques

• National patient safety goals and other relevant regulatory

standards (e.g., CMS core

measures, pay for performance indicators, and never events)

• Nurse-sensitive indicators

• Data management (e.g., collection tools, display techniques,

data analysis, trend

analysis, control charts)

•Analysis of errors (e.g., Root Cause Analysis [RCA], Failure

Mode Effects Analysis

[FMEA], serious safety events)

• Communication (e.g., hands-off communication, chain-of-

command, error disclosure)

• Participate in executive patient safety rounds

• Simulation training in a variety of settings (e.g., disasters,

codes, and other high-risk](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bh1-230107175604-a8918d31/75/B-H1-The-first-issue-that-jumped-out-to-me-is-that-the-presiden-docx-57-2048.jpg)

![Institute of Medicine. (2003). Health professions education: A

bridge to quality.

Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2004). Keeping patients safe:

Transforming the work environment

of nurses. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2005). Building a better delivery system:

A new

engineering/health care partnership. Washington, DC: National

Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2008). Retooling for an aging America:

Building the healthcare

workforce. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2009). Redesigning continuing education

in the health

professions. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2010). Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

initiative on the future

of nursing, at the Institute of Medicine. Retrieved on February

16, 2010, from

http://www.iom.edu/Activities/Workforce/Nursing.aspx

Interprofessional Professionalism Collaborative. (2008).

Interprofessional

professionalism: What’s all the fuss? [PowerPoint slides].

Presented at the

American Physical Therapy Meeting on February 7, 2008, in

Nashville, TN.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bh1-230107175604-a8918d31/75/B-H1-The-first-issue-that-jumped-out-to-me-is-that-the-presiden-docx-118-2048.jpg)

![National Institutes of Health. (2009). Family history and

improving health [PDF

document]. Retrieved from panel statement:

http://consensus.nih.gov/2009/familyhistorystatement.htm

46

National Priorities Partnership. (2008). National priorities and

goals: Aligning our efforts

to transform america’s healthcare. Washington, DC: National

Quality Forum.

National Research Council. (2005). Advancing the nation’s

health needs: NIH research

training programs. Washington. DC: National Academies Press.

Nelson, E., Batalden, P., & Godfrey, M. (2007). Quality by

design: a clinical

microsystems approach. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Nelson, E. C., Godfrey, M. M., Batalden, P. B., Berry, S. A.,

Bothe, A. E., McKinley,

K.E. et al. (2008). Clinical microsystems, Part 1. The building

blocks of health

systems. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient

Safety, 34(7),

367-378.

O’Connell, M. B., Korner, E. J., Rickles, N. M., & Sias, J. J.

(2007). Cultural competence

in health care and its implications for pharmacy Part 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bh1-230107175604-a8918d31/75/B-H1-The-first-issue-that-jumped-out-to-me-is-that-the-presiden-docx-121-2048.jpg)