The narrator was born into slavery but had a relatively happy childhood, cared for by her kind mistress who taught her to read. When she was 6, her mother died and she learned for the first time that she was a slave. Her mistress also died when she was 12, leaving her to the 5-year-old daughter of her sister instead of freeing her as many had hoped, in accordance with her late mistress's promise to the narrator's mother. She was now at the mercy of a new master and mistress.

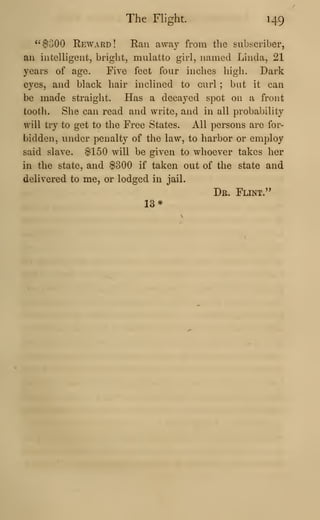

![Fear of Infurrection. lOl

I told liiiii it was one ofsmy friends. " Can you read

them ? " he asked. When I told him I could, he

swore, and raved, and tore the paper into bits.

" Bring me all your letters !

" said he, in a com-

manding tone. I told him I had none. " Don't be

afraid," he continued, in an insinuating way. " Bring

them all to me. Nobody shall do you any harm."

Seeing I did not move to obey him, his pleasant tone

changed to oaths and threats. " Who writes to you ?

half free niggers ? " inquired he. I replied, " 0, no

most of my letters are from white people. Some

request me to burn them after they are read, and

some I destroy without reading."

An exclamation of surprise from some of the com-

pany put a stop to our conversation. Some silver

spoons which ornamented an old-fashioned buffet had

just been discovered. My grandmother was in the

habit of preserving fruit for many ladies in the town,

and of preparing suppers for parties ; consequently

she had many jars of preserves. The closet that con-

tained these was next invaded, and the contents tasted.

One of them, who was helping himself freely, tapped

his neighbor on the shoulder, and said, " Wal done !

Don't wonder de niggers want to kill all de white

folks, when dey live on 'sarves " [meaning preserves].

I stretched out my hand to take the jar, saying, " You

were not sent here to search for sweetmeats."

" And what were we sent for ? " said the captain,

bristling up to me. I evaded the question.

The search of the house was completed, and noth-

ing found to condemn us. They next proceeded to

the garden, and knocked about every bush and vine,

9*](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asx017d-140706111831-phpapp02/85/Incidents-in-the-Life-of-a-Slave-Girl-107-320.jpg)

![] 88 Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.

The dogs will grab her yet." With these Christian

words she and her husband departed, and, to my great

satisfaction, returned no more.

I heard from uncle Phillip, with feelings of unspeak-

able joy and gratitude, that the crisis was passed and

grandmother would live. I could now say from my

heart, " God is merciful. He has spared me the an-

guish of feeling that I caused her death."](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asx017d-140706111831-phpapp02/85/Incidents-in-the-Life-of-a-Slave-Girl-194-320.jpg)

![194- Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

our brief interview was over. Early the next morn-

ing, I seated myself near the little aperture to examine

the newspaper. It was a piece of the New York Her-

ald ; and, for once, the paper that systematically abuses

the colored people, was made to render them a service.

Having obtained what information I wanted concern-

ing streets and numbers, I wrote two letters, one to

my grandmother, the other to Dr. Flint. I reminded

him how he, a gray-headed man, had treated a helpless

child, who had been placed in his power, and what

years of misery he had brought upon her. To my

grandmother, I expressed a wish to have my children

sent to me at the north, where I could teach them to

respect themselves, and set them a virtuous example

;

which a slave mother was not allowed to do at the

south. I asked her to direct her answer to a certain

street in Boston, as I did not live in New York, though

I went there sometimes. I dated these letters ahead,

to allow for the time it would take to carry them, and

sent a memorandum of the date to the messenger.

When my friend came for the letters, I said, " God

bless and reward you, Peter, for this disinterested kind-

ness. Pray be careful. If you are detected, both you

and I will have to suffer dreadfully. I have not a

relative who would dare to do it for me." He replied,

" You may trust to me, Linda. I don't forget that

your father was my best friend, and I will be a friend

to his children so long as God lets me live."

It was necessary to tell my grandmother what I

had done, in order that slie miglit ])e ready for the

letter, and prepared to hear what Dr. Flint might say

about my being at the north. She was sadly troubled.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asx017d-140706111831-phpapp02/85/Incidents-in-the-Life-of-a-Slave-Girl-200-320.jpg)

![27^> Incidents in the Lifr of ii Shivc (iirl.

As I lijul c.onstaiit caro of llio child, 1 had liiilo oh

poi'iunity to suo the wonders of tliat ^roat city; hut I

watc/hod ilio tide of lilb that flowed thn)u«r]i tlie streets,

and found it a stranj^e contrast to tlie staj^nation in our

Southern towns. Mr. Ihuee took liis little daughter

to spend some days witli fricnids in Oxford Crescent,

and of course it was necessary for me to accompany

h(M-. T had heard much of tlie systematic; metliod of

English education, and 1 was very (h^sirous that my

dear Mary should steer straiglit in the midst of so

inucli ])r()|)riety. 1 closely ohserved lier little play-

mates and their nurses, being ready to take any lessons

in the science of good management. Tlie chihlren were

more rosy Mum American children, but 1 did not see

that they (hff(M'ed materially in other respects. They

were like all children — sometimes docile and some-

times wayward.

W(^ next went to StcwcMiton, in l>(^.rkshire. It was a

small town, said to be the i)()()r(^st in the county. 1 saw

men working in th(^ lields for six shillings, and seven

shillings, a w(»,ek, and women for sixpence, and seven-

pence, a day, out of which tlu^y boarded themselves.

Of course they lived in the most primitive manner; it

could not be otherwise, wh(M*e a woman's wages for an

entire day were not sullicient to l)uy a pound of meat.

They paid very low rents, and their clothes were made

of the cheapest fabrics, though much better than could

have been procured in the United States for the same

money. 1 had heard much about the o])])ressi()n of the

poor in Kurope. I'he ))e()pl(^ 1 saw ai'ound me wore,

many of them, among the poorest poor. ]int when 1

visited them in thi^r little thatcluMl cottages, I felt that](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asx017d-140706111831-phpapp02/85/Incidents-in-the-Life-of-a-Slave-Girl-282-320.jpg)

![A Vifit to Englaiiel. 277

the condilioii ol' ovcii the nicanosL mid most ignorant

among them was vastly superior to the condition of tlio

most favored slaves in America. They labored hard ;

but they were not onh^-ed out to toil while the stars

were in the sky, and driven and slashed by an over-

seer, through lieat and cold, till the stars shone out

again. Their homes were very humble ; but they were

j)rotected by law. No insolent patrols could come, in

the dead of night, and Hog them at their pleasure.

The father, when he closed his cottage door, felt safe

with his family around him. No master or overseer

could come and take from him his wife, or his daugh-

ter. They must separate to earn their living; but the

parents knew where their children were going, and

could conununicate with them by letters. The rela-

tions of husband and wife, parent and child, were too

sacred for the richest noble in the land to violate with

impunity. Much was being done to enlighten these

])oor ])eo|)le. Schools were established among them,

and benevolent societies were active in efforts to amel-

iorate their condition. Inhere was no law forbidding

them to learn to read and write ; and if they helped

each other in spelling out the l>ibl(^, they were in no

danger of thirty-nine lashes, as was the case with my-

self and ])oor, pious, old uncle Fred. 1 repeat that the

most ignorant and the most destitute of these peasants

was a thousand fold better oif than the most pampered

American slave.

1 do not iUmy that the poor are oppressed in Europe.

1 afn not dis[)()sed to paint their condition so rose-

colored as the Jlon. Miss Murray paints the condilion

of the slaves in the United States. A small portion

lit](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/asx017d-140706111831-phpapp02/85/Incidents-in-the-Life-of-a-Slave-Girl-283-320.jpg)