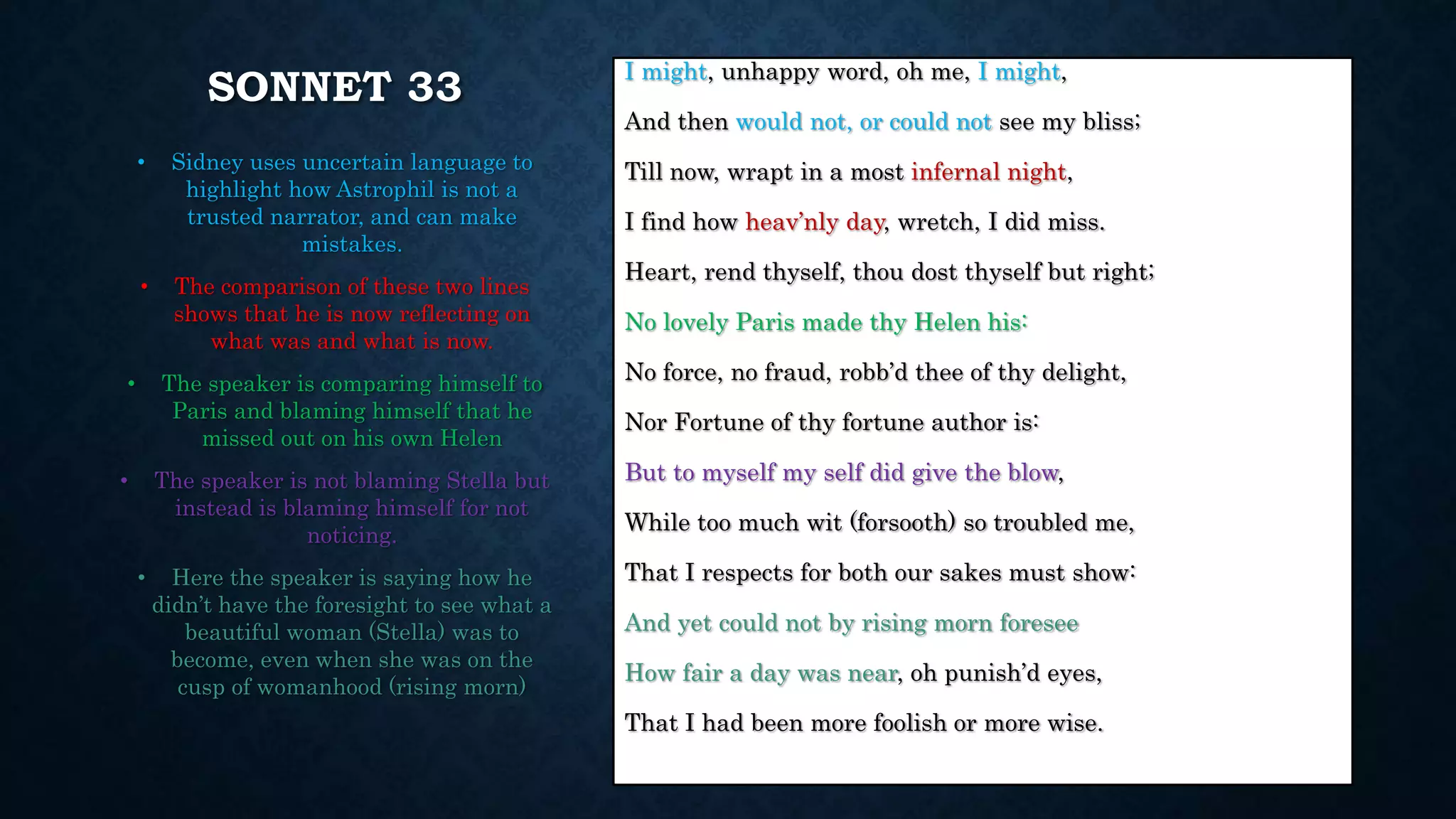

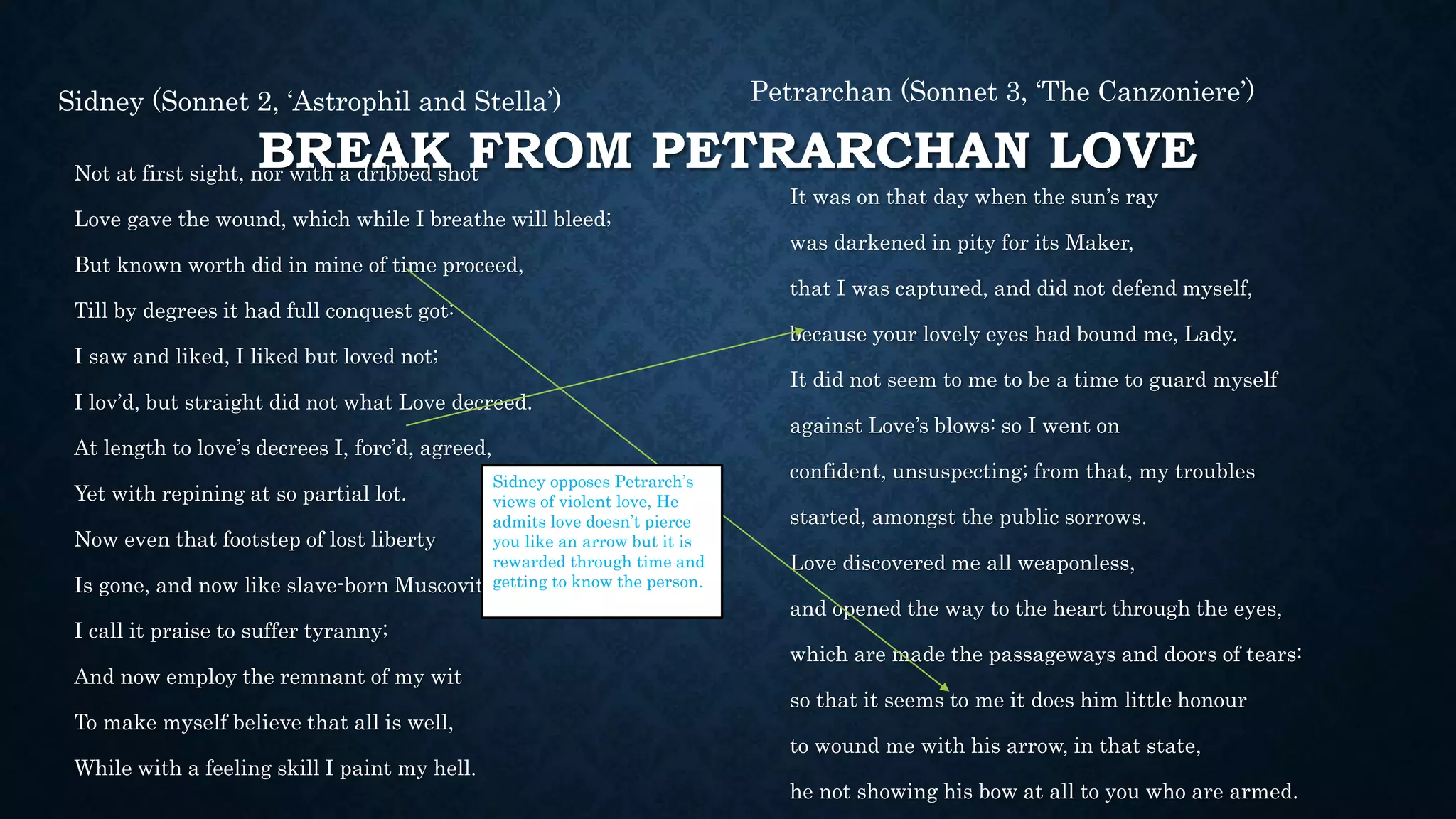

The document discusses Sir Philip Sidney's collection of poems "Astrophil and Stella" and how it both adheres to and departs from conventions of Petrarchan love. While some sonnets depict the themes of longing and frustration typical of Petrarchan poems, Astrophil's pursuit of the married Stella brings the morality of his actions into question. The document analyzes specific sonnets and songs that show how Sidney both incorporates typical Petrarchan devices but also subverts expectations by having Astrophil admire Stella's inner and outer beauty rather than using violent language of love. The document concludes Sidney aimed to inspire a more rational approach to love compared to the conventions established by Petrarch.