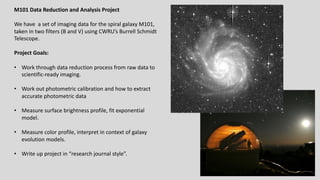

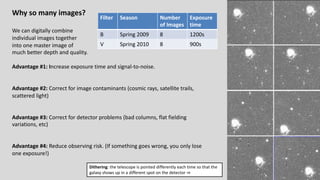

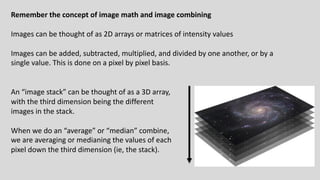

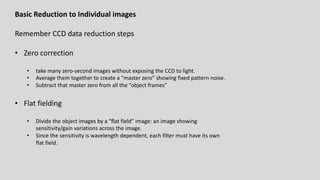

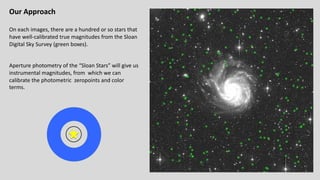

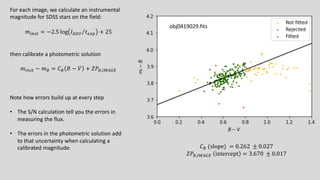

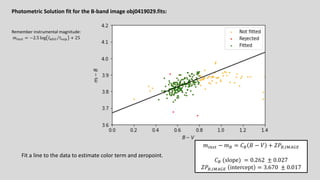

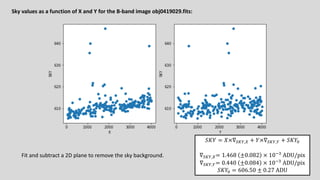

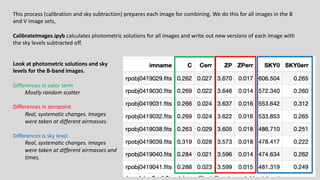

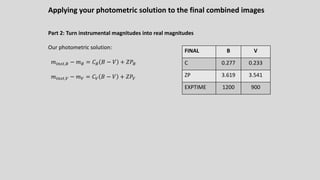

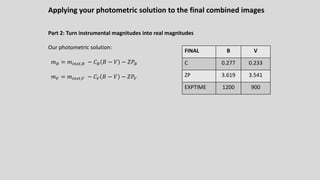

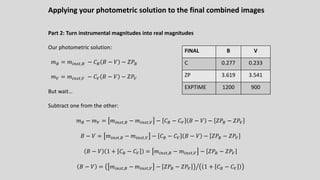

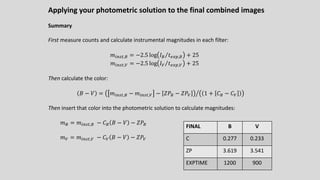

The M101 data reduction and analysis project aims to process imaging data of the spiral galaxy M101 from the Burrell Schmidt telescope using two filters (B and V). The project involves steps like photometric calibration, measuring surface brightness and color profiles, and combining individual images for enhanced quality by correcting for various image contaminants. The final goal is to prepare scientific-ready images and write up the findings in a research journal style.