The document provides guidance for writing an essay on human services delivery models, particularly focusing on the strengths and weaknesses of face-to-face and virtual service models for remote communities. It outlines a structured approach for critically analyzing these models, considering various population groups and the challenges faced by human services workers. The essay should encompass a thorough critique of existing literature, arguments supporting each service model, and an exploration of professional development strategies for enhancing service delivery skills.

![for a lot of legwork. It doesn’t need wealth, but it does take

thought, some

ingenuity and resourcefulness, and more than a little loving care

to cre-

ate a home that is really your own.’19

Displays of furniture ensembles and of complete interiors were

not

only visible inside the bodies of stores, they were also installed

in shop

windows which could be viewed from the street. By the early

twentieth

century the three-walled interior frame had become a familiar

sight in

department store windows. It had its origins in the theatrical

stage set

and the domestic dramas of the decades around the turn of the

century.

A 1925 American manual for ‘mercantile display’ advised that

‘the installing

of a design of this character is well worth the effort as it lends

itself to the

display of a varied line of merchandise’.20 The same manual

also included

a display of living-room furniture, explaining that, ‘The

furniture is

arranged in a manner to show [it] off to good advantage, using

the

necessary accessories such as the lamp, book rack, pictures

etc.’, rein-

forcing the, probably tacit, knowledge of professionals in that

field that

consumers needed to be shown just enough of an interior for

their](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assessment3essaytipsswk405thetaskessaywhen-221227042135-10e12232/85/Assessment-3Essay-TIPSSWK405-The-taskEssayWhen-docx-34-320.jpg)

![out of one

sheet of metal’, he demonstrated the industrial designer’s

characteristic

concern for economical manufacture. He was also interested in

ensuring

that the bed could be dusted and dismantled easily and, above

all, that it

‘possess[ed] sheer, graceful lines’.18 When he moved his focus

on to the

showroom in which the bed was to be displayed his main

preoccupation 159

147_166_Modern_Ch 8:Layout 1 30/5/08 18:25 Page 159

Sparke, Penny. The Modern Interior, Reaktion Books, Limited,

2008. ProQuest Ebook Central,

http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/asulib-

ebooks/detail.action?docID=480991.

Created from asulib-ebooks on 2018-10-11 14:10:42.

C

op

yr

ig

ht

©

2

00

8.

R

ea](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assessment3essaytipsswk405thetaskessaywhen-221227042135-10e12232/85/Assessment-3Essay-TIPSSWK405-The-taskEssayWhen-docx-100-320.jpg)

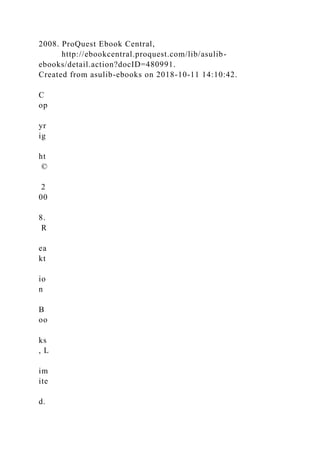

![Many of the same requirements underpinned the industrial

designers’ work for train interiors. Henry Dreyfuss’s settings

for the 20th

Century Limited were strikingly controlled, modern-looking,

and decep-

tively spacious. His use of concealed lighting enhanced the

luxurious

ambiance that he had set out to create. Muted colours – blue,

grey and

brown – were combined with new materials, including cork and

Formica.

‘Fully enclosed by glass and rounded surfaces, protected from

weather

and engine-soot by air-conditioning, and lulled by radio music,

they

[the passengers] could forget they were travelling as they

experienced a

rubber-cushioned ride.’22 In the train’s main lounge and

observation

car, the designer’s use of top lighting and the addition of metal

strips to

the columns combined with a number of other features to create

an

extremely elegant travelling environment. Loewy’s interior

designs for

the Broadway Limited provided a similarly comfortable

experience for its

passengers. The train’s luxurious interior was enhanced by the

presence

of a circular bar as glamorous as anything that could have been

found in

a New York or a Parisian nightclub.

In spite of their significant impact on interior spaces in the

com-

mercial sphere the industrial designers made very little](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/assessment3essaytipsswk405thetaskessaywhen-221227042135-10e12232/85/Assessment-3Essay-TIPSSWK405-The-taskEssayWhen-docx-114-320.jpg)