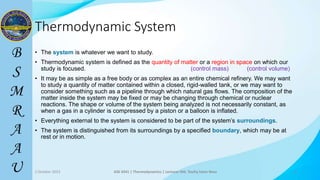

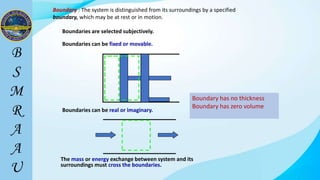

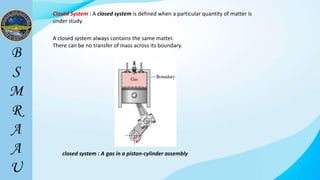

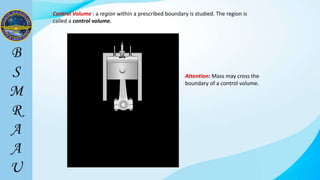

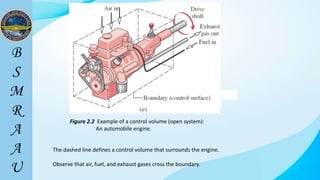

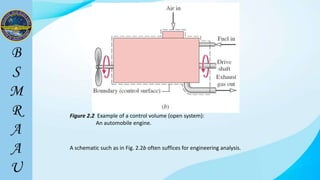

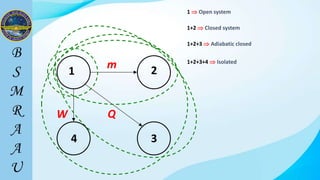

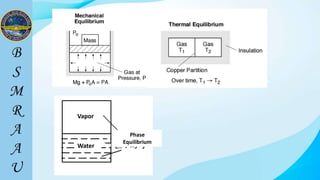

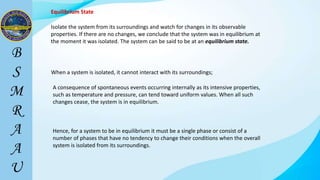

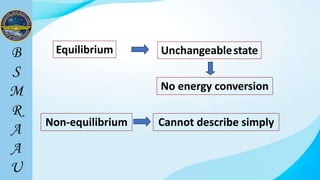

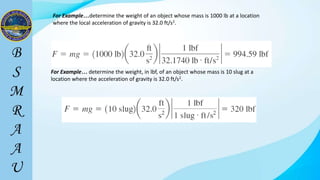

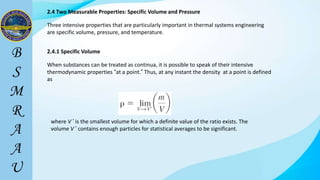

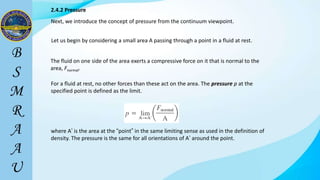

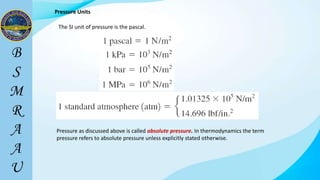

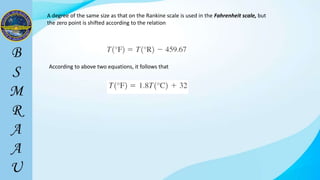

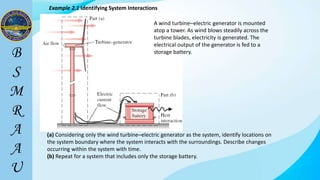

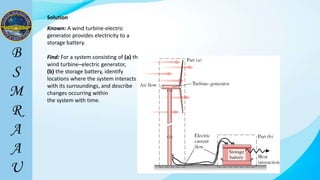

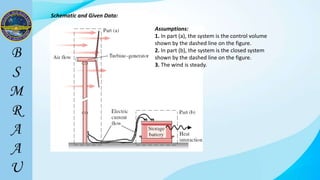

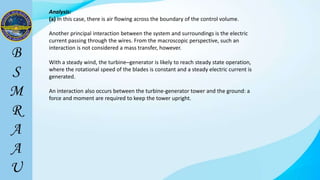

This document outlines a thermodynamics course taught by Md. Toufiq Islam Noor. It introduces key concepts in thermodynamics including systems, properties, processes, equilibrium, and units. Specific topics covered include defining closed, open, and isolated systems, intensive/extensive properties, equilibrium states, and standard SI and other units for mass, length, time, and force. Examples are provided for calculating weight and converting between units.