This document outlines the course plan for an advanced quantitative techniques course for PhD students. The course covers topics such as simple and multiple regression analysis, model specification, hypothesis testing of means, dealing with issues like multicollinearity and heteroskedasticity in regression models, and time series and panel data analysis. The course will be taught over one semester with weekly lectures and assignments. Students will be evaluated based on individual assignments, a group research project, midterm and final exams.

![LECTURES &

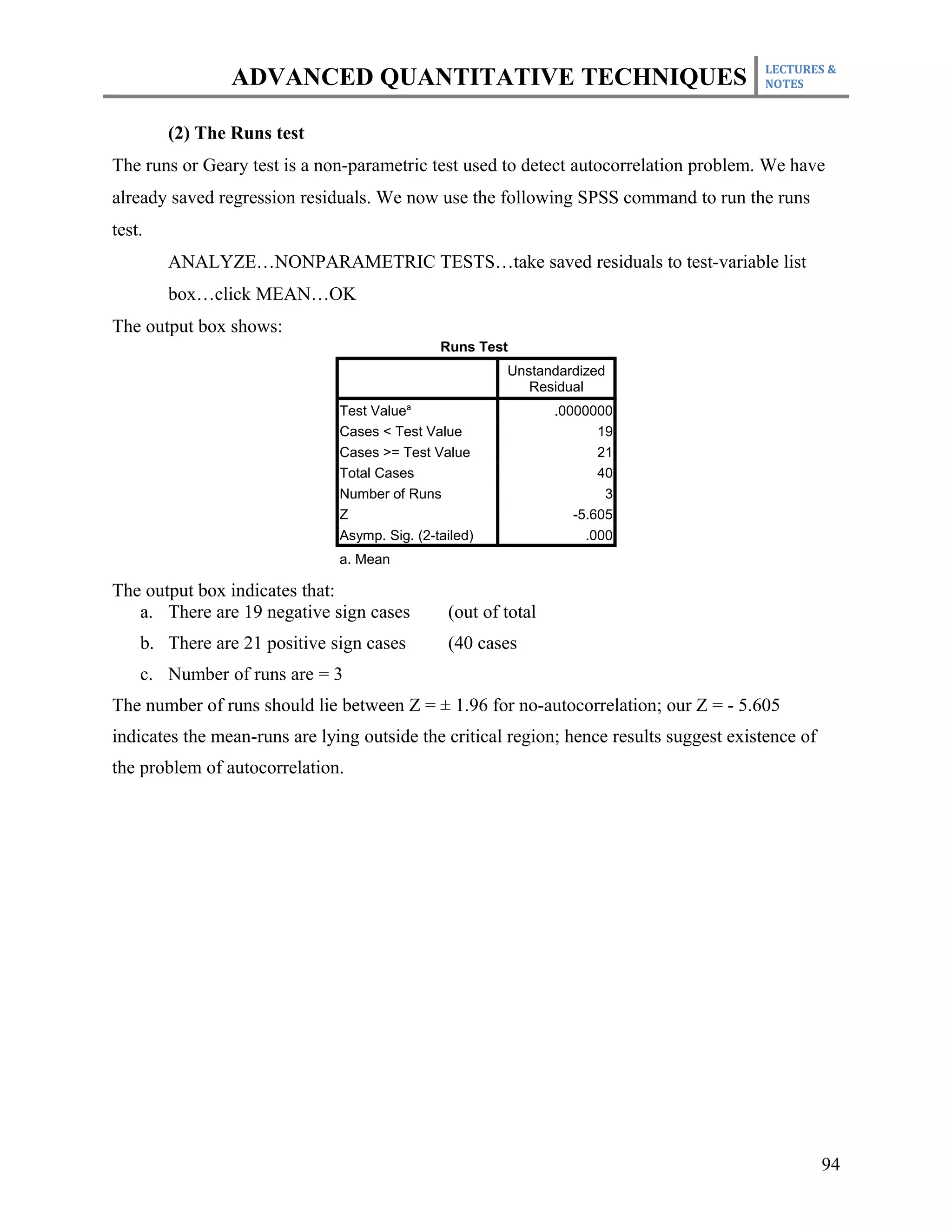

ADVANCED QUANTITATIVE TECHNIQUES NOTES

This is normally referred to as homoscedasticity assumption, and if this

Assumption is violated, then we face the problem of heteroscedasticity.

3. Based on assumption 1 and 2 , we can say that variable μ i has a normal

distribution, i.e.,

μ i ~ N(0, б2)

4. Error term for one observation is independent of the error term of other

observation, i.e., μ i and μ j are not correlated, or

Cov (μ i and μ j ) = 0

This is no-serial-autocorrelation assumption, and if this assumption is

violated, then we have autocorrelation problem.

5. μ i is independent if the explanatory variables (X), that is, the μ i and μ j are

not correlated.

Cov (X μ ) = ∑{[Xi - ∑ (Xi)] [ μ i -∑ (μ i)]} = 0

6. The explanatory variable (Xi) are not linearly correlated to each other; they

do not affect each other. If this assumption is violated, then we face the

multicolinearity problem.

7. There is no specification problem, that is,

a) Model is specified correctly, mathematically, from the economic

theory point of view.

b) Functional form of the model ( i.e., linear or log-linear or any other

form) is correct.

c) Data on dependent and independent variables have correctly collected,

i.e., there is no measurement error.

1.9 BLUE properties of estimator:

Given the aforementioned assumptions of the classical linear regression model, the Least -

Square estimator (β) possess some ideal properties.

1. It is linear.

2. It is unbiased, i.e., its average or expected value is equal to its true

value.

ˆ

Ε( βi ) = βi

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aqt-instructor-notes-final-121206004954-phpapp01/75/Aqt-instructor-notes-final-14-2048.jpg)

![LECTURES &

ADVANCED QUANTITATIVE TECHNIQUES NOTES

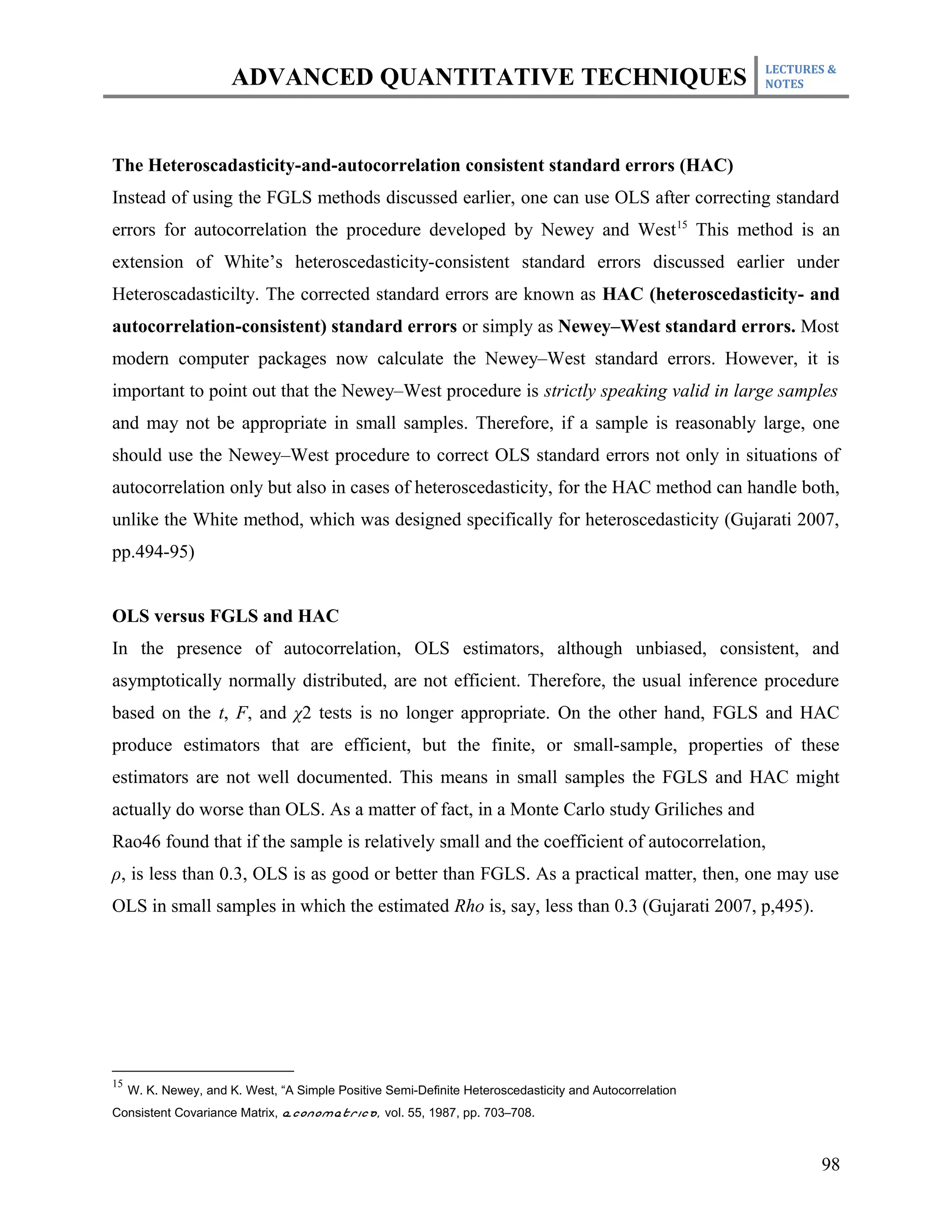

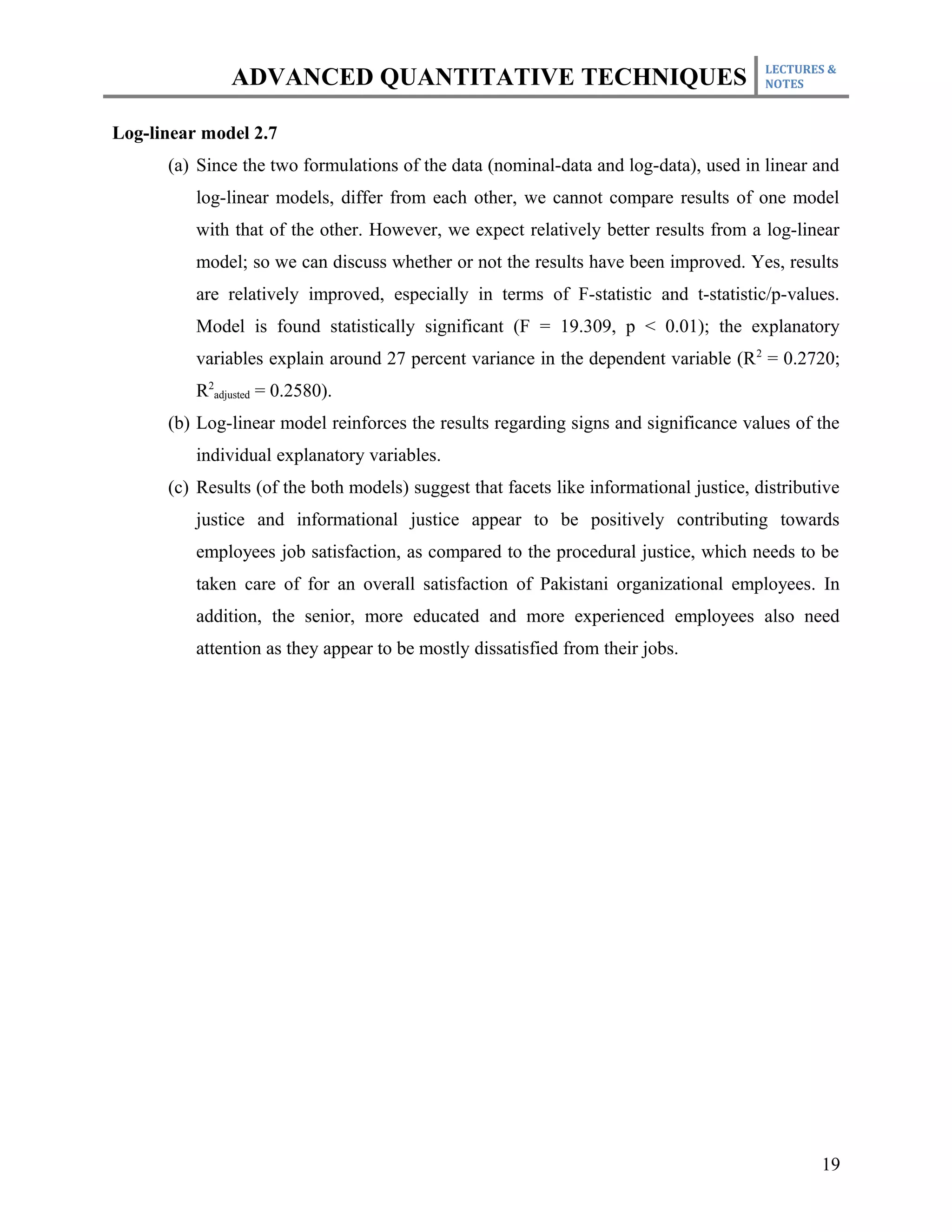

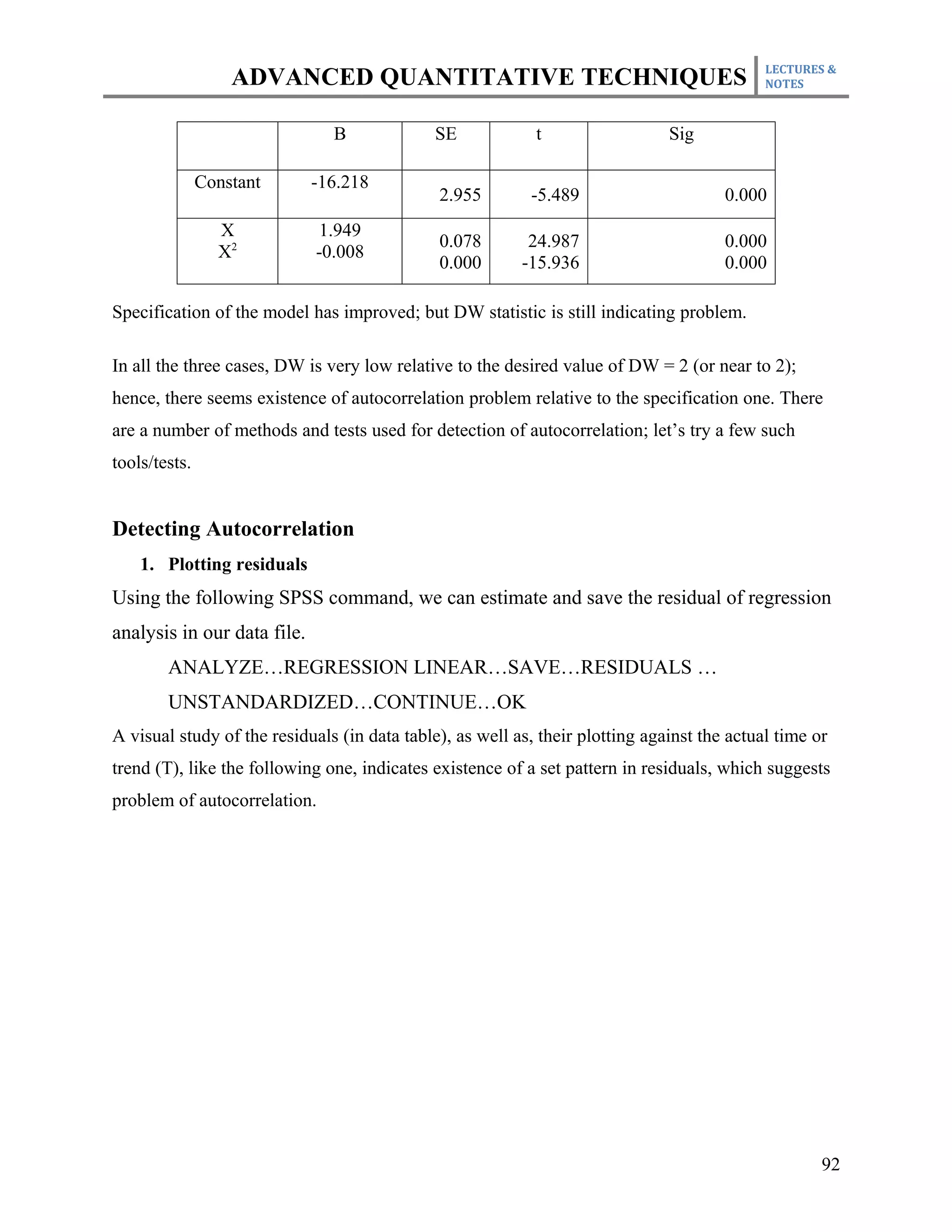

(3) Using DW statistic

The Durban-Watson d or DW statistic ranges between 0 and 4; where:

a. There is no-autocorrelation around a d = 2 (between du and 4-du)

b. Then there are two ‘indecision zones’ on both sides of ‘No-autocorrelation’ zone.

c. On both extreme ends, ‘positive autocorrelation’ and ‘negative autocorrelation’ zones

exist.

[ ] [ ]

+ [ Indecision ] No [ Indecisive ] -

Autocorrelation [ Zone ] Autocorrelation [ Zone ] Autocorrelation

[ ] [ ]

0 __________dl__________du________2______4-du_________4-dl____________ 4

How to test? The estimated model (9.2) estimates DW = 0.123, which needs to compare with

the tabulated values provided in the Durban-Watson d statistic tables. We have n = 40 and K’ = 1

(k excluding intercept). At n = 40 and K’= 1, table provides dl = 1.442 and du = 1.544. As

calculated DW = 0.123 falls below du, that suggests existence of the problem of autocorrelation.

Remedies (Gujarati 2007, pages 485-495)

There are two major remedies, namely:

(a) When the ‘coefficient of autocorrelation’ (rho = ρ) is not known, then remedy is

‘first-differencing’, that is:

(Yt – Yt-1) = β1(Xt – Xt-1) + et (9.6a)

(b) When ρ is known, then remedy is:

(Yt – ρYt-1) = α + β1(Xt – ρXt-1) + et (9.6b)

The First-Differencing method

Using TRANSFORM and COMPUTE command in SPSS, we can generate lagged variables,

namely:

LagY = Yt-1

LagX = Xt-1

Further generating FDY = Yt – Yt-1 = Yt – LagY (9.7a)

and FDX = X = Xt-1 = Xt – LagX (9.7b)

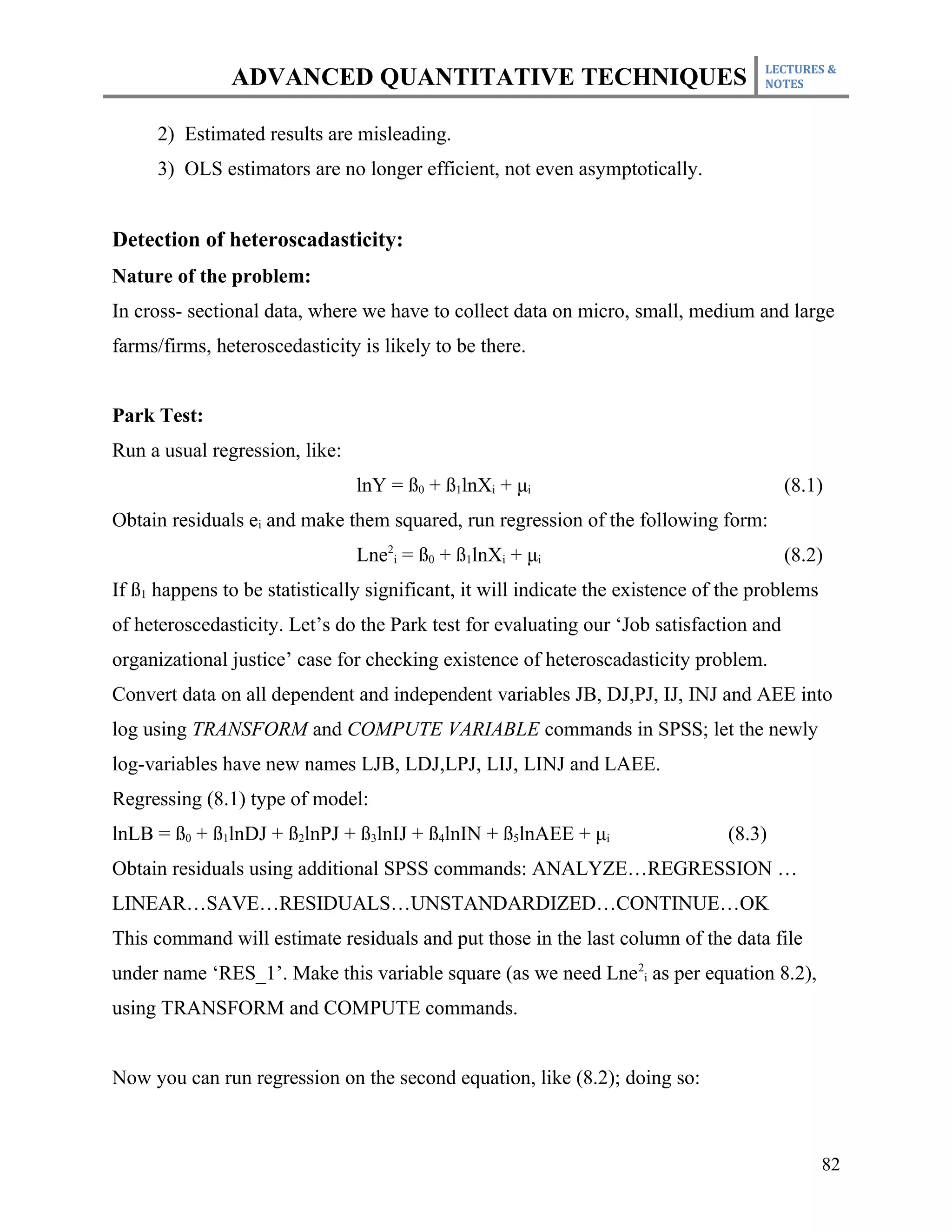

95](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aqt-instructor-notes-final-121206004954-phpapp01/75/Aqt-instructor-notes-final-95-2048.jpg)