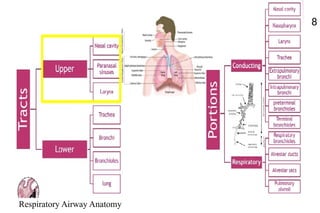

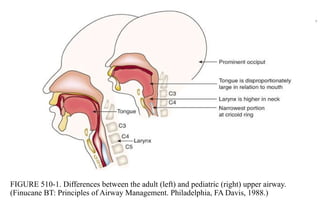

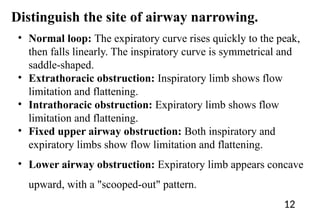

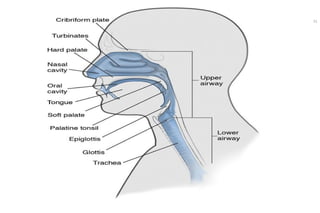

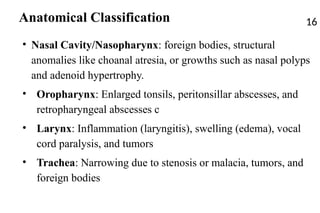

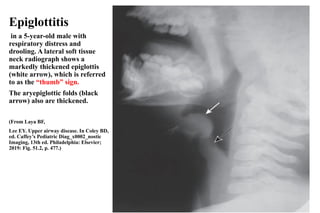

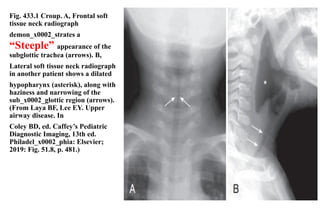

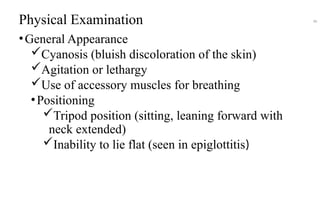

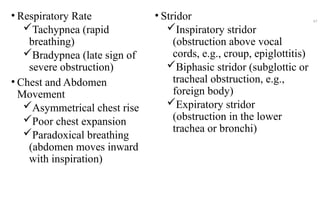

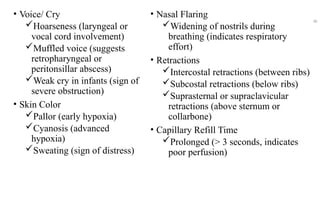

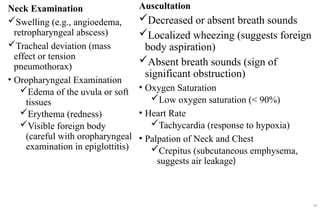

This document outlines the approach to managing acute upper airway obstruction, focusing on its causes, clinical assessment, and treatment strategies. It emphasizes the differences in airway obstruction across age groups and details various conditions leading to obstruction, especially in children. The importance of immediate intervention and detailed history and physical examination for effective management is also highlighted.