The document provides a comprehensive overview of intestinal obstruction, detailing its types, clinical features, and diagnostic approaches including imaging techniques like CT and ultrasound. It discusses the causes of both small bowel and large bowel obstructions, highlighting intrinsic and extrinsic factors, as well as differentiating simple from complicated obstructions. Additionally, it emphasizes the importance of identifying the transition point and includes various imaging findings associated with specific causes, like Crohn's disease, neoplasia, and adhesions.

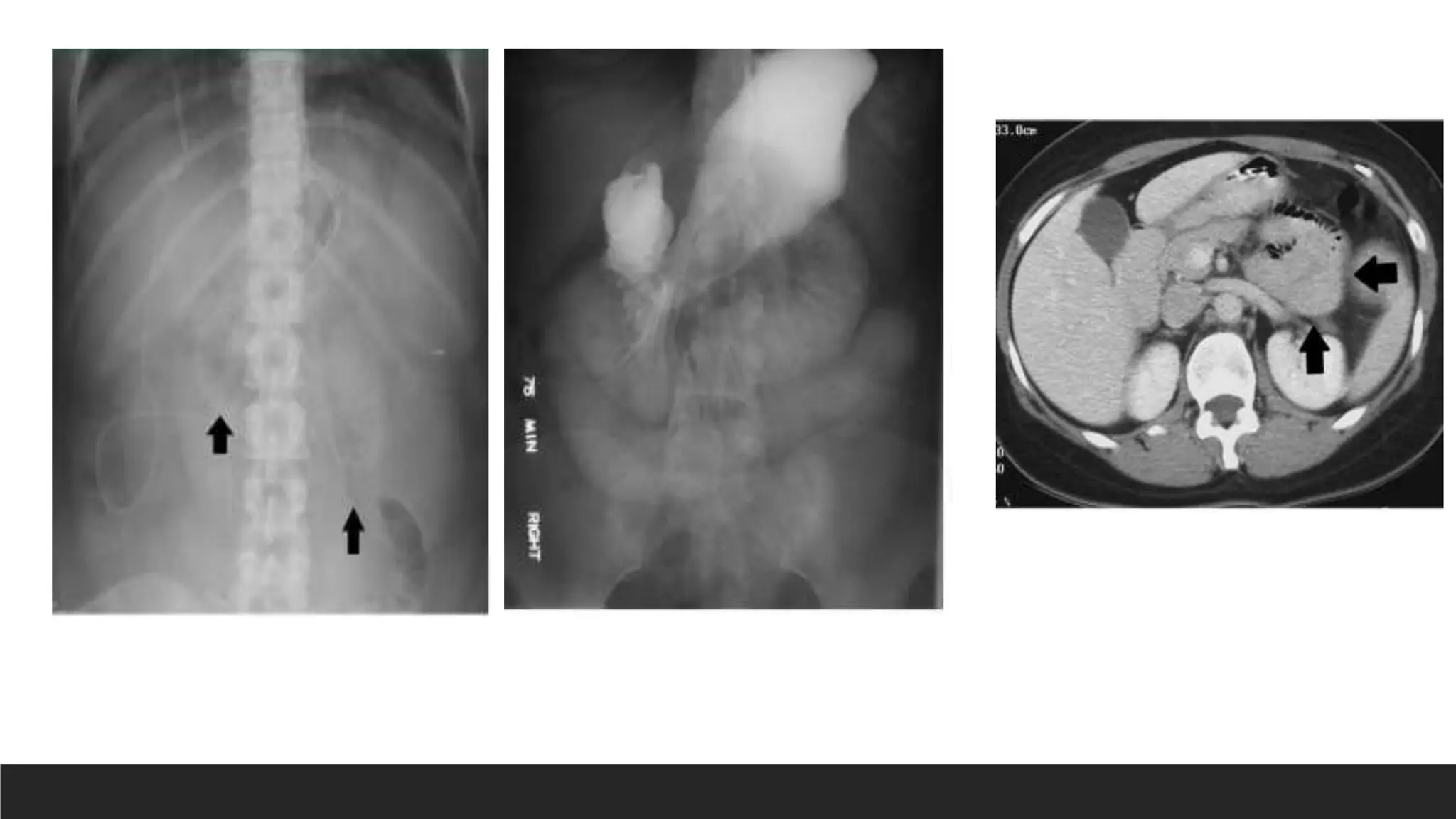

![Colorectal carcinoma

Common sites-sigmoid colon and splenic flexure.

The most common site of perforation[3%–8%] in LBO is not at the site of the tumor but

at the cecum

Barium enema

seen as filling defects

appear as exophytic or sessile masses

may be circumferential -apple core sign

CT

Asymmetric and short-segment colonic wall thickening

or an enhancing soft-tissue mass centered in the colon that narrows the colonic lumen

Pericolonic lymph nodes](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/approachtointestinalobstruction-240503145117-07bbd539/75/Approach-to-intestinal-obstructions-pptx-58-2048.jpg)