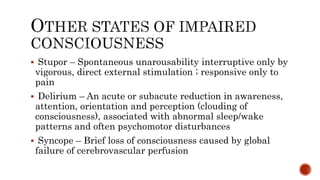

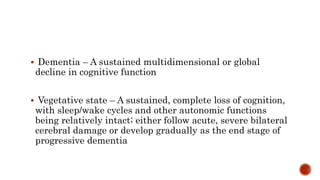

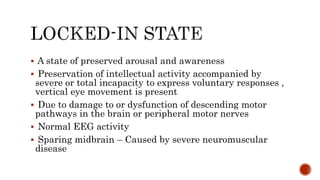

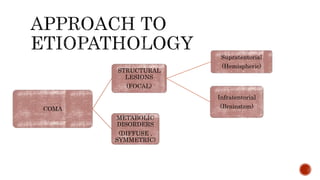

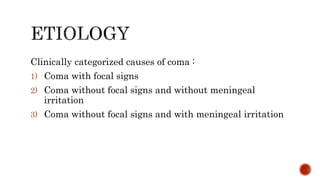

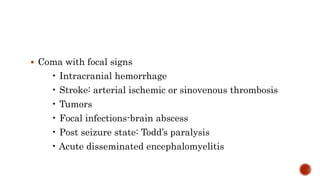

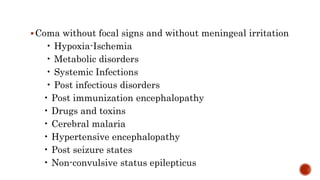

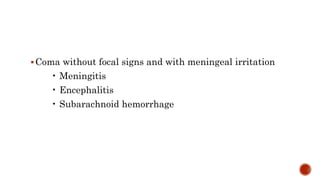

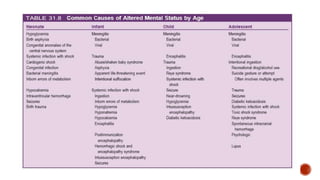

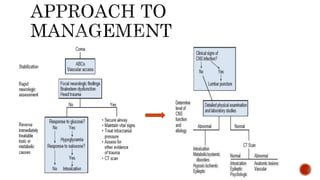

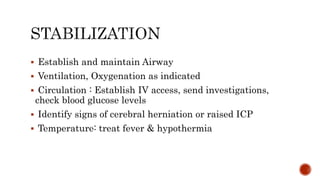

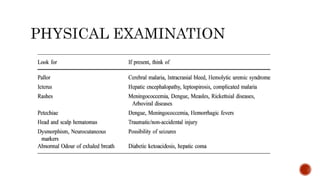

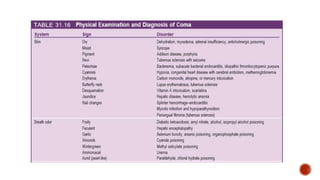

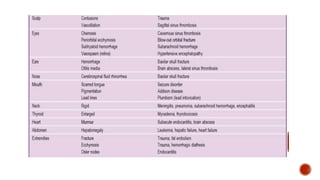

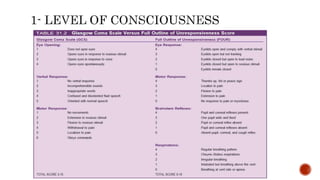

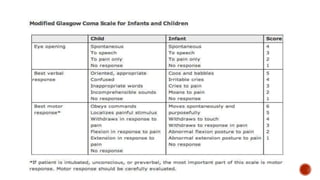

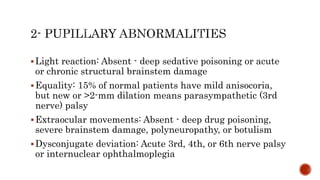

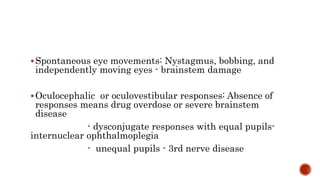

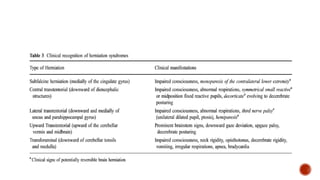

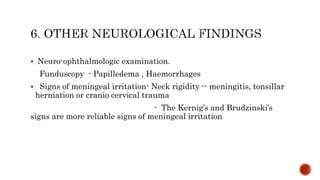

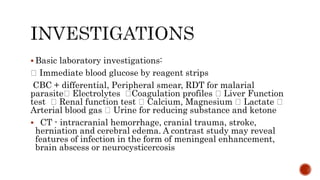

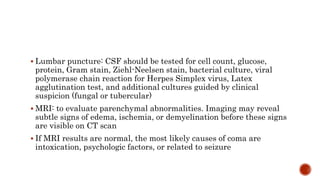

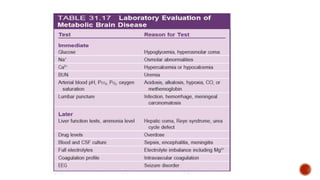

This document provides an overview of coma, including definitions, terminology, causes, assessment approach, management, and prognosis. It defines coma as a state of unarousable unresponsiveness and discusses related altered states of consciousness like stupor, delirium, and vegetative state. Common causes of coma are categorized as those with focal signs, without focal signs but without meningeal irritation, and without focal signs but with meningeal irritation. The rapid assessment approach is outlined, including stabilization, history, neurological exam, investigations like CT/MRI, and management of identified issues. Prognosis depends on etiology, depth and duration of impaired consciousness, with infectious causes generally having better outcomes than hypoxic-