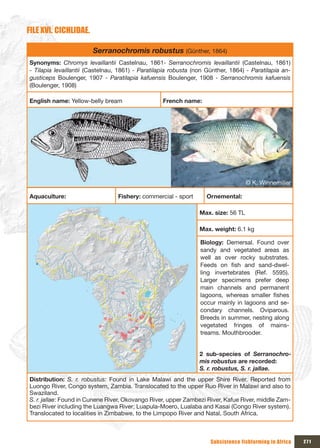

This document provides guidelines for setting up small-scale fish farming operations to address lack of protein in subsistence communities in Africa. It outlines the objectives of providing essential information to start fish production with minimal costs using local resources. The document discusses constraints to consider, such as environmental, social, and cultural factors that will influence appropriate techniques. It also notes limitations of existing manuals, such as a focus on commercial operations rather than subsistence needs, and lack of adaptation to local conditions. The guidelines cover setting up a program, technical aspects, management, and addressing various constraints.

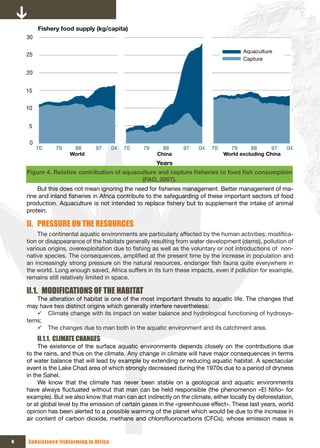

![LIST OF PHOTOS

Part I - INTRODUCTION AND THEORICAL ASPECTS 1

Part II - PRACTICAL ASPECTS 27

Photo A. Measurement of a slope (DRC) [© Y. Fermon]. 56

Photo B. Example of rectangular ponds in construction laying in parallel (Liberia) [© Y. Fermon]. 68

Photo C. Cleaning of the site. Tree remaining nearby a pond {To avoid}(DRC); Sites before cleaning (Liberia)

[© Y. Fermon]. 77

Photo D. Channel during the digging (Liberia) [© Y. Fermon]. 80

Photo E. Stakes during the building of the dikes (Liberia) [© Y. Fermon]. 82

Photo F. Dikes. Slope badly made, destroed by erosion (DRC)[© Y. Fermon]; Construction (Ivory Coast)

[© APDRA-F](CIRAD). 89

Photo G. Example of non efficient screen at the inlet of a pond (Liberia) [© Y. Fermon]. 93

Photo H. Example of filters set at the inlet of a pond in Liberia [© Y. Fermon]. 93

Photo I. Mould and monks (Guinea). The first floor and the mould; Setting of the secund floor [© APDRA-F]

(CIRAD). 100

Photo J. First floor of the monk associated with the pipe (Guinea) [© APDRA-F](CIRAD). 102

Photo K. Top of a monk (DRC)[© Y. Fermon]. 102

Photo L. Building of a pipe(Guinea) [© APDRA-F](CIRAD). 103

Photo M. Setting of a fences with branches (Liberia) [© Y. Fermon]. 108

Photo N. Compost heap. [Liberia © Y. Fermon], [© APDRA-F](CIRAD). 126

Photo O. Use of small beach seine (Liberia, Guinea, DRC) [© Y. Fermon]. 132

Photo P. Mounting, repair and use of gill nets (Kenya, Tanzania) [© Y. Fermon]. 132

Photo Q. Cast net throwing (Kenya, Ghana) [© F. Naneix, © Y. Fermon]. 134

Photo R. Dip net (Guinea) [© Y. Fermon]. 135

Photo S. Traps. Traditionnal trap (Liberia); Grid trap full of tilapia (Ehiopia) [© Y. Fermon]. 136

Photo T. Fish packing in plastic bags (Guinea, (Ehiopia) [© Y. Fermon, © É. Bezault]. 138

Photo U. Hapas in ponds (Ghana) [© É. Bezault]. 143

Photo V. Concrete basins and aquariums (Ghana) [© Y. Fermon]. 145

APPENDIx 187

Photo W. Nests of Tilapia zillii (Liberia) [© Y. Fermon]. 219

Photo X. Claroteidae. Chrysichthys nigrodigitatus [© Planet Catfish]; C. maurus [© Teigler - Fishbase];

Auchenoglanididae. Auchenoglanis occidentalis [© Planet Catfish]. 232

Photo Y. Schilbeidae. Schilbe intermedius [© Luc De Vos]. 233

Photo Z. Mochokidae. Synodontis batensoda [© Mody - Fishbase]; Synodontis schall [© Payne - Fishbase]. 234

Photo AA. Cyprinidae. Barbus altianalis; Labeo victorianus [© Luc De Vos, © FAO (drawings)]. 235

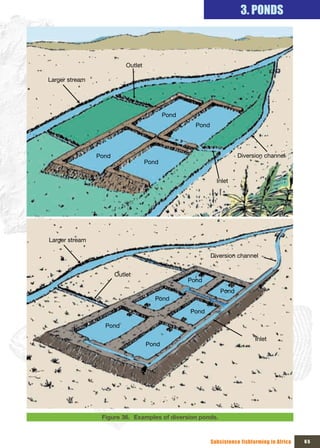

Photo AB. Citharinidae. Citharinus gibbosus; C. citharus [© Luc De Vos]. 235

Photo AC. Distichodontidae. Distichodus rostratus; D. sexfasciatus [© Fishbase]. 236

Photo AD. Channidae. Parachanna obscura (DRC) [© Y. Fermon]. 236

Photo AE. Latidae. Lates niloticus [© Luc De Vos]. 237

xviii Subsistence fishfarming in Africa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-18-320.jpg)

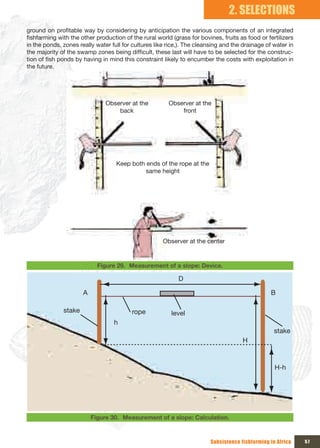

![(the maximum error is lower than 6 cm by 20 m of distance). It requires a team of three people. An

observer installs a stake with the starting point A whose site is marked and maintains the rope on

the graduation corresponding to h. The observer in B also maintains the rope against the same

graduation, then upwards moves the cord on the second stake or to the bottom of the slope, until

the person placed at the center indicates that the plumb level is with horizontal with the well tended

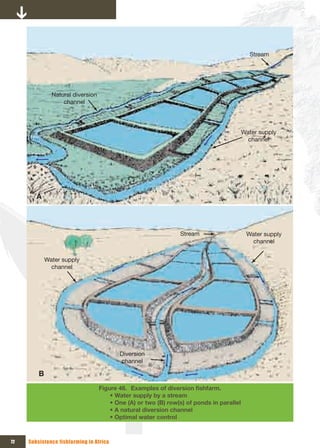

rope. If one does not have a mason level, a water bottle can be enough. There H is known. It is then

possible to measure the H-h difference. The slope P in % will be then:

P = (H-h) x 100 / D

With D = distance between has and B.

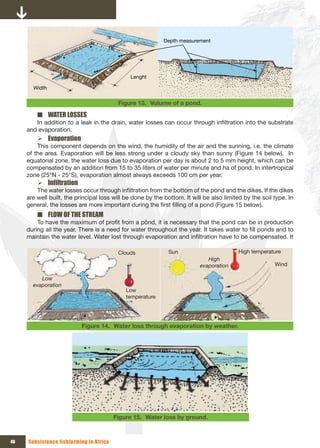

II.4. THE OTHER PARAMETERS

II.4.1. THE ACCESSIBILITY OF THE SITE

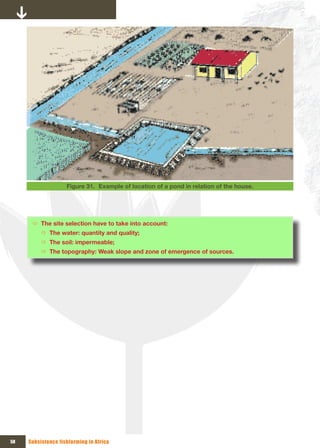

A good fishfarmer will daily control the pond. At least, he comes each day to survey the pond,

he gives to eat per day to his fish if necessary. Each week, he reloads the composts, he cuts grasses

on the dikes… It is necessary thus that the pond is not too far from the house of the fishfarmer and

that there are no barriers between the pond and the house (river in rainy season, for example). It is

advised to live more close as possible to its pond to supervise it against the thieves (Figure 31, p. 58).

II.4.2. THE POSSIBILITY OF BUILDING WITH LOWER COSTS

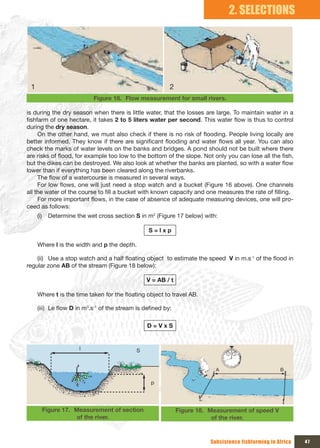

It was already seen that one will not build a pond where the slope is very strong because the

downstream dike should be very large and thus expensive for a pond of reduced surface. For each

work, one compares the required effort with the benefit which one can draw.

If there are the choice, one thus will prefer an open site at a site full with tree trunks which are ne-

cessary to be remove with all the roots. One also will choose a ground without rocks or large stones.

II.4.3. THE PROPERTY LAND

It is a question of knowing the owner of the site on which will be established the future series of

ponds. One will have to make prospection. One

of the solutions is to require to the villagers to see

by themselves which are the sites of proximity.

Then, to evaluate the various sites according to

the criteria above.

In margin of the ponds, the maintenance or

the plantation of the trees and other plant spe-

cies will make it possible in very broken ground

not only to protect the grounds against ero-

sion, but also to consider the exploitation of the

Photo A. Measurement of a slope (DRC) [© Y. Fermon].

56 Subsistence fishfarming in Africa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-74-320.jpg)

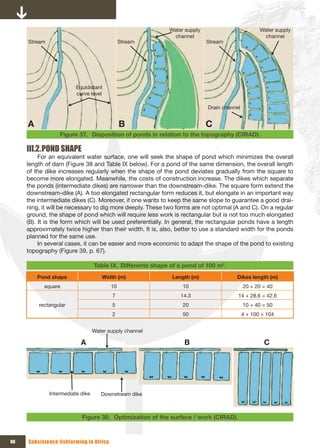

![supply channels of the ponds. However, the fact

that it is the same water which passes in all the

ponds can bring problems as for the propagation

of diseases. Indeed, if a pond is contaminated,

the risk of contamination of the others and to lose

all its production is important. There will be also

problems during drainings of the ponds. The re-

quired slope is also more important in total.

9 In parallèle (Photo B, p. 68): The ponds are

independent from each other, each one being

supply directly from the supply channel. Wa-

ter is not re-used after having crossed a pond.

At contrario of ponds in series, it is possible to

isolate without problems each ponds, and thus

Photo B. Example of rectangular ponds in to limit the risks of contamination. Drainings are

construction laying in parallel (Liberia) done independently and the slope is the same for

[© Y. Fermon]. all the ponds.

III.5. SIZE AND DEPTH OF THE PONDS

The ponds are characterized by their size, their form and their depth. We saw in au paragraphe

II.1, p. 45 the calculation of the surface and the volume of a pond.

III.5.1. THE SIZE

The individual size of sunken ponds and diversion ponds can be decided upon by the farmer,

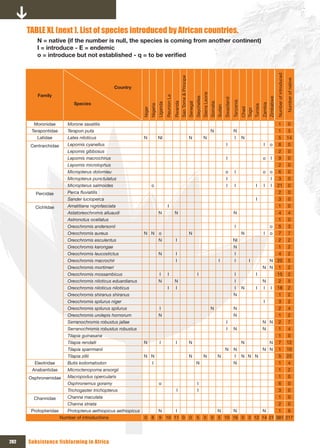

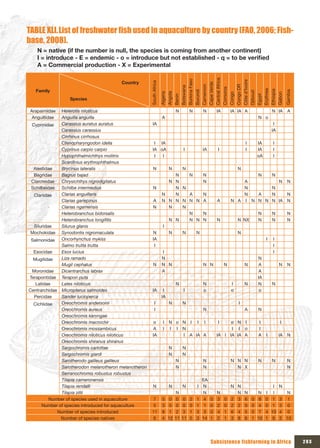

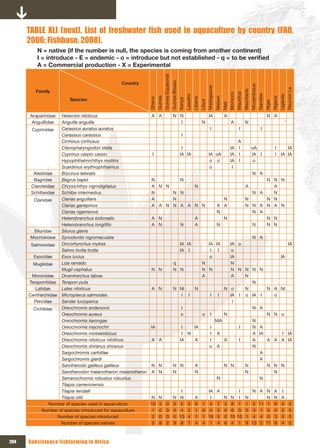

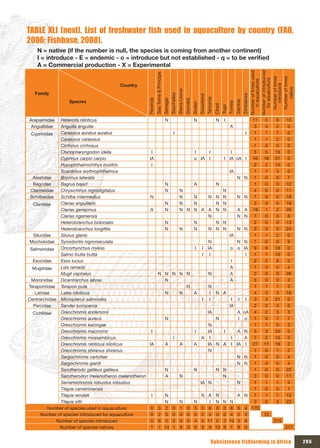

considering the following factors (Table X and Table XI below):

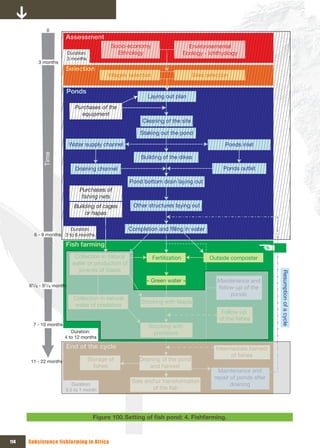

9 Use: A spawning pond is smaller than a nursery pond, which is in turn smaller than a fatte-

ning pond.

9 Quantity of fish to be produced: A subsistence pond is smaller than a small-scale commer-

cial pond, which is in turn smaller than a large-scale commercial pond.

9 Level of management: An intensive pond is smaller than a semi-intensive pond, which is in

turn smaller than an extensive pond.

9 Availability of resources: There is no point in making large ponds if there are not enough

resources such as water, seed fish, fertilizers and/or feed to supply them.

9 Size of the harvests and local market demand: Large ponds, even if only partially harves-

ted, may supply too much fish for local market demands.

Table X. Size of fattening ponds.

Type of fishfarming Area (m2)

Subsistence 100 - 400

Small-scale commercial 400 - 1000

Large-scale commercial 1000 - 5000

Table XI. Resource availability and pond size.

Small pond Large pond

Small quantity Large quantity

Water

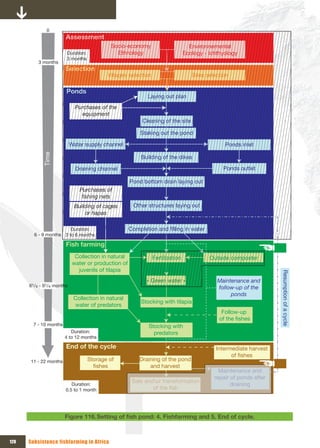

Rapid filling/draining Slow filling/draining

Fish seed Small number Large number

Fertilizer / feed Small amount Large amount

Small harvest Large harvest

Fish marketing

Local markets Town markets

68 Subsistence fishfarming in Africa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-86-320.jpg)

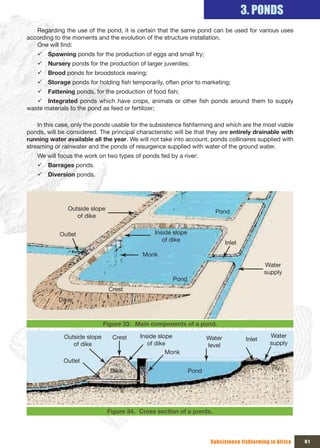

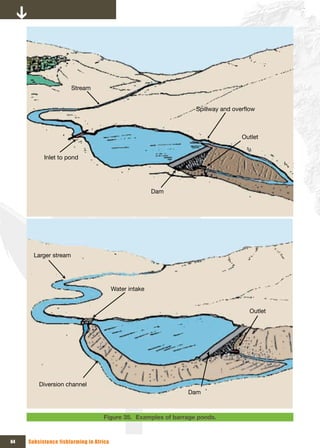

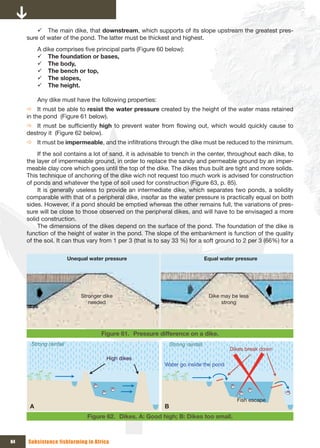

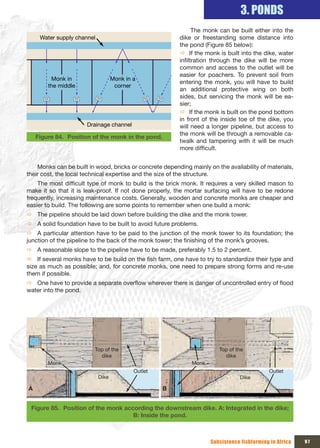

![3. PONDS

Photo C. Cleaning of the site. On left: Tree remaining nearby a pond {To avoid}(DRC);

On right: Sites before cleaning (Liberia) [© Y. Fermon].

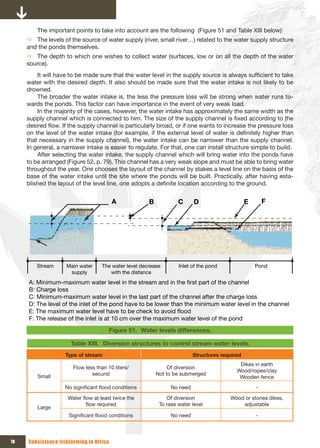

III. WATER SUPPLY: WATER INTAKE AND CHANNEL

The water supply includes water intake, the main channel and the small canals which bring water

from the main channel to the pond.

The principal water intake are used to regulate overall and to derive the water supply from a pond

or a group of ponds. They have primarily the role to ensure a regular water supply, which may be

regulated according to the present conditions.

The water inlets are settled, if possible, against the water current to prevent the transport of ma-

terial that the river carries, to the ponds. This canal fed in theory by a constant flow, but adjustable,

is made to bring water to the upper part of the ponds built so that their complete draining can be

made whatever the level of water in the bottom of the valley. This condition is very important and

must be strictly respected. In too often cases where it is not, the ponds are just simple diverticula

of rivers whose flood demolish the dike and where the fish enter and leave easily. One makes some

surveys to see whether it does not arise particular difficulties (presence of rocks in particular).

The main elements of a water intake are:

Ö A diversion structure being used to regulate the level of the watercourse and to ensure that it is

sufficient to feed the water intake without drowning.

Ö A device of regulation of the level of entry (and flow) inside the structure itself, being used to

regulate the water supply of the ponds; such a device is generally connected to the transport of

water structure;

Ö A structure of protection of the entry, for example stilts to prevent any deterioration of the water

intake due to the debris.

One will use an open or free level water intake in which the levels of supply are not controlled and

where the water catch functions under all the conditions of flow. This system is simple and relatively

cheap, but it generally requires a reliable water supply which does not vary too much.

Subsistence fishfarming in Africa 77](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-95-320.jpg)

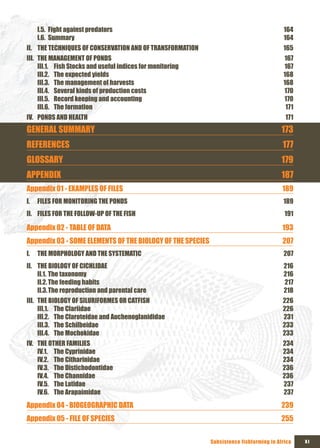

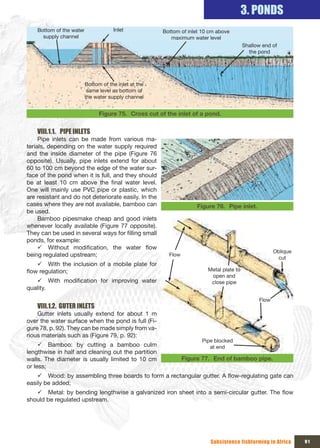

![Table XIV. Channel dimensions.

Small farm Medium farm

A few l/s 20-50 l/s

Bottom width 20 to 30 cm 50 cm

Water depth 20 to 40 cm 60 to 80 cm

Side slope 1.5:1 1.5:1

Top width 60 to 100 cm 150 to 180 cm

Bottom slope 0 1 ‰ (1 cm per 10 m)

to the channel a too strong slope. So, despite these precautions, the water of the channel is turbid,

it should be provided on the water course of the mud tanks or conceived widenings in such way that

the current velocity is enough low there, to allow the deposit of the suspended matter.

After the last checks of the definite location, one can carry out the earthwork of the dry channel,

while starting where one wants, according to the needs for the moment. This operation is done in

three times (Figure 54 below):

1. First, to dig the central part with distant vertical walls of a width equal to the width of the bottom,

then one adjusts the slope longitudinally along the bottom, and one proceeds to the cut of the slopes

(sloping).

2. Be carefull to leave in place (in the axis or on the edges) the stakes whose tops must be used

Cnttre line Centre line Cut out sides of channel

Leave 10 Dig out

cm of earth remaining

at the 10 cm of earth

bottom Bottom width Bottom width Bottom width

Mark the Move the rope

line of the out to the slope

channel stakes

with centre, Cut out sides of

slope and Rope channel

bottom Leave

stakes sections of Remove

earth sections of

Rope earth

Stretch a Check

Remove centre cross-section

rope along and bottom

the bottom with wooden

stakes gauge

stakes

Masons level

Stakes Final channel

bottom

Figure 54. Channel digging.

Photo D. Channel during the digging (Liberia) [© Y. Fermon].

80 Subsistence fishfarming in Africa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-98-320.jpg)

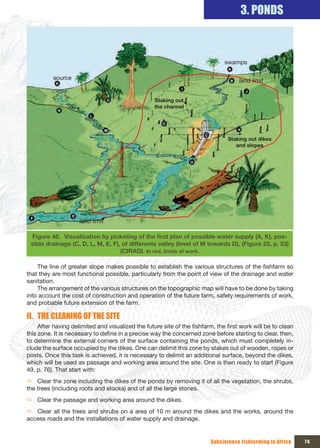

![V. THE PICKETING OF THE POND

On the area delimited by the draining and

water supply channels, one can now delimit the

ponds. This operation is called the picketing or

staking. It must allow to represent the site of the

dikes as well as dimensions and the heights of

the dikes with stakes. It will thus be necessary

to respect, thereafter, these dimensions during

work (Figure 57 below and Photo E opposite).

The staking is done using stakes which

must have a sufficient height to allow spoil or

fill later without risk to discover the buried ends

or to cover the air ends. One will on the whole

have 4 rows of pegs for the main dike and the 2

side dikess and 3 for the upstream dike. These

stakes will be spaced from each other of 2 m. A

spacing between the rows of pegs will be func- Photo E. Stakes during the building of the

tion of dimensions of the dikes. dikes (Liberia) [© Y. Fermon].

Water supply channel Water supply channel

Location of the pond Location of the pond

Drain channel Drain channel

Figure 57. Picketing of the pond and the dikes.

82 Subsistence fishfarming in Africa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-100-320.jpg)

![3. PONDS

soil of better bearing pressure. The bench or top

of the dike must have a width higher than 1 m to

allow later handling of the seine during fishings.

An establishment of the dike starts with the es-

tablishment of the foundation.

The downstream-dike which surround the

fishfarming site is the object of a pressure exer-

ted by the water of the ponds. Water saturates

the soil in bottom with the dike (Figure 64, p. 85).

The downstream-dike must be made conse-

quently to avoid any infiltration. On the sandy

soils, it must have a base broader than on the

argillaceous soils.

When water, in its way, meets a ground wa-

ter located low, the water of the basement of the

Figure 63. Digging of the cut-off trench for pond is in balance with the expanse of water

clay core. since it lost its pressure. In this successful case,

there is no more infiltration once the water-log-

Clay core lowers saturation line ged soil with water.

Hydraulic The calculation of the height of the dam to

Water line gradients be built should take into account (Figure 65 op-

8:1 posite):

4:1

8:1 9 Desired depth of water in the pond.

9 Freeboard, i.e. upper part of the dike

which should never be immersed. It varies from

25 cm for the very small ponds in derivation to

100 cm (1 m) for the barrage ponds without di-

Clay core version canal.

9 The dike height that will be lost during

Figure 64. Clay core and saturation of the

settlement, taking into account the compres-

dikes.

sion of the subsoil by the dike weight and the

Settlement (dike heigh lost) settling of fresh soil material. This is the settle-

Freeboard (25 - 100 cm)

ment allowance which usually varies from 5 to

20 % of the construction height of the dike.

Accordingly, two types of dike height may be

defined (Figure 66 opposite):

Depth of water

Ö The design height DH, which is the height the

dike should have after settling down to safely

Figure 65. High of a dike. Depth; Freeboard; provide the necessary water depth in the pond.

Settlement. It is obtained by adding the water depth and the

freeboard.

Ö The construction height CH, which is the

(15%) height the dike should have when newly built

SH and before any settlement takes place. It is equal

FB (30) to the design height plus the settlement height.

The construction height (CH in cm or m) sim-

CH

{153} DH WD ply from the design height (DH in cm or m) and

(130) (100) the settlement allowance (SA in %) as follows:

CH = DH / [(100 - SA) / 100]

Figure 66. High of the structure (definitions

and example in the texte).

Subsistence fishfarming in Africa 85](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-103-320.jpg)

![If the maximum water depth in a diversion pond of medium size is 100 cm and the freeboard

30 cm, the design height of the dike will be DH = 100 + 30 = 130 cm. If the settlement allowance is

estimated to be 15%, the required construction height will be:

CH = 130 / [(100 - 15) / 100] = 130 / 85 = 153 cm.

A dike rests on its base. It should taper upward to the dike top, also called the crest or crown.

The thickness of the dike thus depends on:

Ö The width of the crest; and.

Ö The slope of the two sides.

The dike must make 4 m at the base for a minimum 1 m of height, globally. The slope of the

dike at the bottom of the slope of the pond is more important to limit erosion and to allow an easier

access to the bottom of the pond (Figure 60, p. 83, Figure 66 and Table XV below). The width of the

top of the dike is related to the depth of water and the part which the dike must play for circulation

and/or transport:

Table XV. Examples fo dimension of dikes.

Surface (m2) 200 400 - 600

Quality of soil Good Fair Good Fair

Water depth (max m) 0.80 1.00

Freeboard (m) 0.25 0.30

Height of dike (m) 1.05 1.30

Top width (m) 0.60 0.80 1.00

Dry side, slope (SD) (outside) 1.5:1 2:1 1.5:1

Wet side, slope (SW) (inside) 1.5:1 2:1 2:1

Base width (m) 4.53 6.04 6.36 8.19

Settlement allowance (%) 20 20 15 15

Construction height (m) 1.31 1.31 1.53 1.53

Cross-section area (m2)

3.36 4.48 5.63 7.26

Volume per linear m (m2)

Crest

(> 1.00 m)

Crest width at least

equals water depth (1.00)

(0.40)

Dry side

slope

Wet side slope {1.5:1}

{2:1}

Water

depth

Clayey soils

Increase as sand increase

Figure 67. Dimension of a dike.

86 Subsistence fishfarming in Africa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-104-320.jpg)

![3. PONDS

Photo F. Dikes. On left: Slope badly made, destroed by erosion (DRC)[© Y. Fermon];

On right: Construction (Ivory Coast) [© APDRA-F](CIRAD).

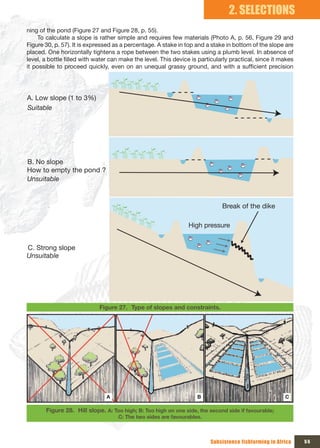

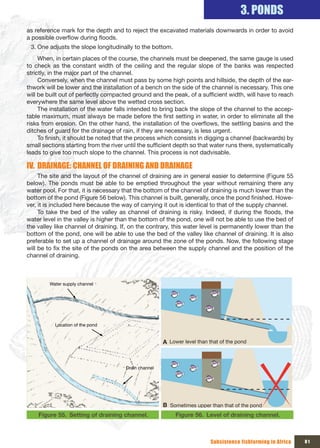

VII. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE PLATE (BOTTOM)

The pond having to be completely empty without remaining water puddle pools there, one ar-

ranges the bottom or the plate in soft slope towards the outlet (Figure 72 below).

The construction of the bottom of the plate is done by clearing the bumps to remain slightly in

top of the projected dimensions. For the embankments, a particular care is given here to the com-

paction and the choice of the quality of the soil to be used, because one is in a case similar to that

of the supply channel which is permanently submerged.

In the case of small ponds, the bottom must be with a soft slope (0.5 to 1.0%), since the water

inlet to the outlet, to ensure an easy and complete dry setting of the pond. One must always make

sure that the entry of the outlet is slightly below the lowest point of the bottom of the pond.

For the ponds whose surface is rather important (more than 4 ares) the installation of ditches of

drainage towards the emptying device is very useful. It is preferable to ensure a complete dry setting

by a network of not very deep ditches of draining and having a slope of 0,2 %, rather than to seek to

create a slope on all the plate of the pond.

When the bottom of the plate is entirely regularized, one will carry out the digging of the drains

converging of the edges towards the zone of draining. The drains are small channels built to facilitate

I = Inlet I

I

O = Outlet

I

O

A B O C O

Figure 72. The bottom or plate. Direction of the slope (A)

and drain setting: In ray (B); As «fish bones» (C).

Subsistence fishfarming in Africa 89](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-107-320.jpg)

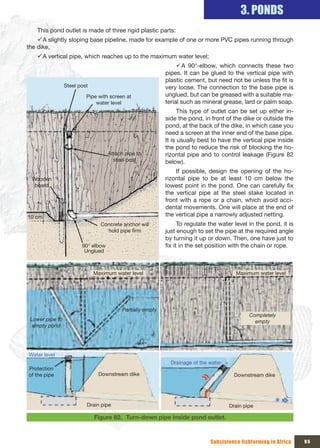

![3. PONDS

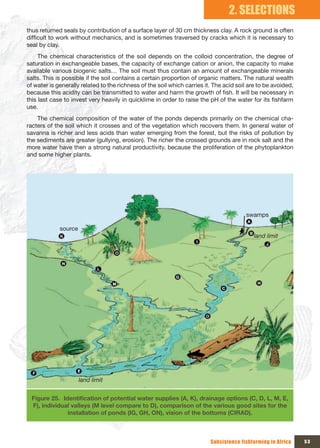

VIII.1.5. THE FILTRATION

At the inlet, filtering devices of water are usually used:

9 To improve water quality by reducing turbidity and while allowing to eliminate certain organic

matters in suspension, such as vegetable debris.

9 To limit the wild fish introduction, which can take food, transmit infections and diseases and

reduce the production of the ponds. The carnivorous species can destroy the fish stock, in particular

smaller ones.

It is possible to make various types of more or less effective structures and more or less heavy

to implement. Initially, one can put a rather coarse stopping like a grid, on the level of the general

water supply channel or the pond to prevent the large debris to pass into the ponds. For the aquatic

animals, one will use finer structures. Often, simple net, sometimes mosquito net, were used on

the inlet (Photo G below). However, either these grids are filled very quickly and thus require a daily

cleaning, or they are destroyed because not solid

enough. One can indeed set up more elaborate

structures, but which often require higher over-

costs. However, it is possible to set up a system

simple, not too expensive and requiring a regular

but nonconstraining maintenance, may be only

one to twice a year, if water is rather clear. It is

a question of making pass the water by gravels,

then by sand filter (Figure 81 and Photo H, p. 93).

If the feed water is too turbide and char-

ged in sediment, it is possible to set up a filter

Photo G. Example of non efficient screen at decantation before its arrival in the pond,. The

the inlet of a pond (Liberia) [© Y. Fermon]. principle is simple. It is enough to install a small

Photo H. Example of filters set at the inlet of a pond in Liberia [© Y. Fermon].

To fill with Filtering mass

the filtering masses Gravel Sand

Wire netting

Debris

Concrete Water supply

channel

Water

Pond

Wild fishes

Dikes

Figure 81. Diagram of an example of sand filter.

Subsistence fishfarming in Africa 93](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-111-320.jpg)

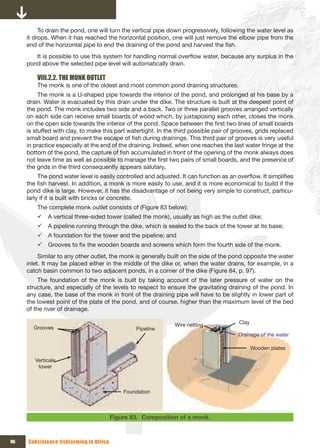

![Clamp

A B

Figure 88. Mould of a monk. A: Front view; B: Upper view.

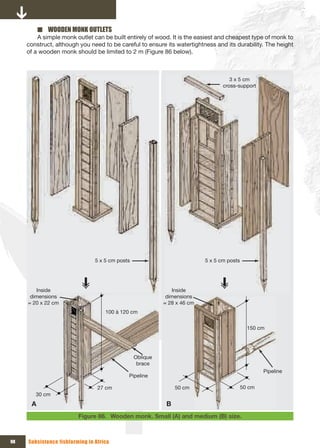

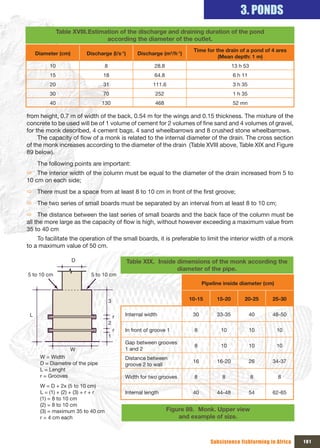

mer invested itself in the research of sand and the gravel, these monks were finally less expensive

than those which are carried out in breeze blocks. Then, this type of formwork undergoes major

changes. As private individuals again, the mould is from now transportable by only one person with

foot or bicycle. The shuttering timber coats oil internally (engines oil of vehicles for example) is thus

carried out above the foundation in order to run the wings and the back of the monk.

As an indication, the dimensions presented in Table XVII below can be adopted, according to the

size of the pond. Thus, for a pond from 0.5 to 2 ha, the formwork to be run will be able to have: 2 m

Table XVII. Informations on the dimensions of the

monk according the size of the pond.

Surface of the

S < 0.5 ha S > 0.5 ha

pond

Height (m) 1.50 2.0,

Bach width (mi) 0.54 0.70

Sides width (m) 0.44 0.54

Depth of concrete 0.12 0.15

Photo I. Mould and monks (Guinea). On left: The first floor and the mould;

On right: Setting of the secund floor [© APDRA-F] (CIRAD).

100 Subsistence fishfarming in Africa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-118-320.jpg)

.

Clay

Photo K. Top of a monk (DRC)

[© Y. Fermon].

The maintenance of the mould requires a

minimum of attention. It is preferable to store it

made so that it becomes not deformed and to

coat it as soon as possible with engine oil. Used

well, a mould can make more than 20 monks.

By leaving some iron stems in the still fresh

concrete to make the junction with the following

stage, it was completely possible to build by

stage a monk of more than 2 m (Photo I, p. 100 and

Photo J above).

The soil used between the small planks to

block the monk must be rich in organic matter in

order to keep its plasticity. Too pure clays often

fissure side of the tube, which is not long in cau-

sing escapes.

The height of water in the pond is thus regu-

lated by the monk thanks to the small boards out

of wooden between which one packs clay (Figure

90 opposite). Water is retained in the pond by this

impermeable layer up to the level of the highest

small board.

Netting at the top of the last small board pre-

Figure 90. Functioning of a monk. vents fish from leaving the pond over the highest

102 Subsistence fishfarming in Africa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-120-320.jpg)

.

small board of the monk. One will always take care that the meshs of netting are smaller than fish

raised in the pond.

When the pond is filled to the last small board, all the water which enters more in the pond,

crosses the grid above the impermeable layer and falls to the bottom of the monk. In this place, it

crosses the dike then leaves the pond while passing by the drain (Photo K, p. 102).

The monk ended, it is essential to equip it with foundations called soles. The sole is also used as

plane surface and hard to catch last fish easily.

The monks of this type are generally provided with drains. One can use a PVC drain or set up

concrete tubes. If one wants to obtain the best results, the drain must have a good foundation whose

construction must be done at the same time as that of the column of the monk (Figure 91 and Photo

L above). The seals of the drains must be carefully sealed to avoid the water escapes.

In the wet environments, because of water abundance which compensates the risks of escape,

the concrete tubes constitute a good technique:

Ö They are cheap: two baggs of cements are enough for 10 m of tube for which it is necessary to

add a half bagg for the seals;

Ö Their section allows an higher capacity that of a pipe of 100 or 120 mms in diameter;

Ö The flat bottom of the tube makes it possible to accelerate the ends of draining, which is very

practical;

Ö It is easy to add a tube when the need is felt some.

However the concrete tubes present also some disadvantages, in particular in the dry zones,

which are as many recommendations:

Ö The mould must be quite manufactured and correctly maintained so that the junctions are en-

casable and remain it;

Ö It is preferable to assemble the tubes before building the dike, it is thus easier to move the water.

One can then install them on a dry and hard soil instead of posing them on mud;

Subsistence fishfarming in Africa 103](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-121-320.jpg)

![Ix.3. BIOLOGICAL PLASTIC

If the ground used can let infiltrate water, it will be necessary to use the technique of “biological

plastic”, to reinforce the sealing of the plate of the pond. This technique allows to reduce the water

leaks and infiltrations by filling the plate and the dikes of a pond built on a ground not impermeable

enough. The realization of the biological plastic is done in the following way:

1. After having regularized the structures well by removing vegetable debris and stones, one

covers all the plate and the future water side of the dikes with waste of pigsty.

2. One recovers then this waste using leaves of banana tree, straw or other vegetable matters.

3. Then, one spreads out a layer of ground over the unit and one rams copiously.

4. Two to three weeks after, the pond can be fill with water.

Ix.4. THE FENCE

The fence prevents the entry of predatory of all species (snakes, frogs, otters…) in the enclosure

of the pond (Figure 98 and Photo M below). It can be made of a netting, that one buries on at least

a 10 cm depth and the higher end turned towards the pond. Metal stakes or of not very putrescible

wood are thus established all the 50 - 90 cm to be used as support with the grid fixed using wire of

fastener. For the bamboos, it will be necessary to think of their replacements after 18 months to the

maximum in tropical zone. Other materials other than netting can be used.

In all the cases, it is advisable to take care that

the fence does not have any hole on the whole of

its perimeter. The second role is also to limit the

poaching which is one of the important causes

of the abandonment of the ponds. The use of the

access doors in the enclosure of the ponds will

have to be, so controlled well.

If necessary, if the piscivorous birds are too

numerous, one can have recourse to the installa-

tion of a coarse net on the ponds and to the use

of scarecrows.

Photo M. Setting of a fences with branches

(Liberia) [© Y. Fermon].

Stream

Pond

Fishponds

Fisherman

Door B

Predators

Dikes

Thief Channel

Controle of water level A

Figure 98. Fences (A).

In scrubs (B); In wood or bamboo (C). C

108 Subsistence fishfarming in Africa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-126-320.jpg)

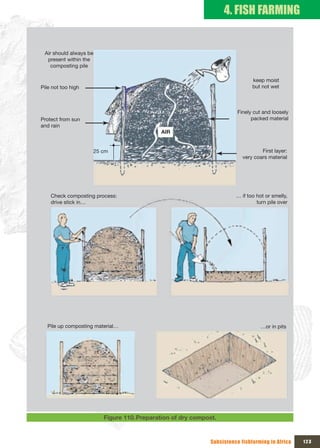

![Installation of a crib in

each of the two shallow

corners

Photo N. Compost heap. [Up, Liberia

Figure 115. Compost heap in crib in a pond.

© Y. Fermon], [Down, © APDRA-F](CIRAD).

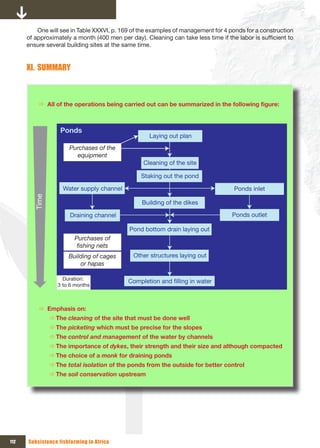

III. SUMMARY

Ö The two steps are:

Ö The fertilization

Ö The expectation of a « green water » which indicate that the pond is ready for

ensemensement

Ö Emphasis on:

Ö The preparation of aerobic and anaerobic compost

126 Subsistence fishfarming in Africa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-144-320.jpg)

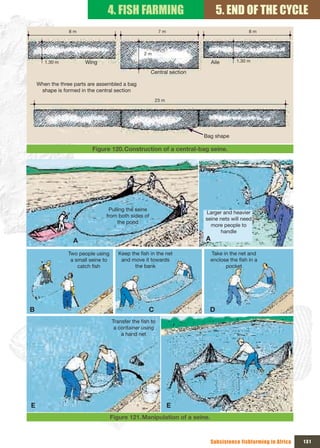

![Photo O. Use of small beach seine (Liberia, Guinea, DRC) [© Y. Fermon].

I.2. GILL NETS

One of the most widely used nets in fres-

hwater capture fisheries is the gill net, which

may also be useful on a farm for selective har-

vesting of larger fish for marketing.

Photo P. Mounting, repair and use of gill nets (Kenya, Tanzania)

[© Y. Fermon].

132 Subsistence fishfarming in Africa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-150-320.jpg)

![Open Closed

net net

Use a castnet

in the water

Photo Q. Cast net throwing (Kenya, Ghana)

[© F. Naneix, © Y. Fermon].

Use a castnet

from a boat

In position Closed

Figure 123. Use of a cast net.

I.4. DIP OR HAND NETS

Dip nets are commonly used on fish farms for handling and transferring small quantities of fish.

They can be bought complete, assembled from ready-made parts or you can make the nets yourself.

A dip net is made of three basic parts (Figure 124 and Photo R, p. 135):

9 A bag, made of netting material suitable in size and mesh type for the size and quantity of

fish to be handled;

9 A frame from which the bag hangs, generally made from either strong galvanized wire or iron

bar (usually circular, triangular or «D» shaped, with fixing attachments for the handle);

134 Subsistence fishfarming in Africa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-152-320.jpg)

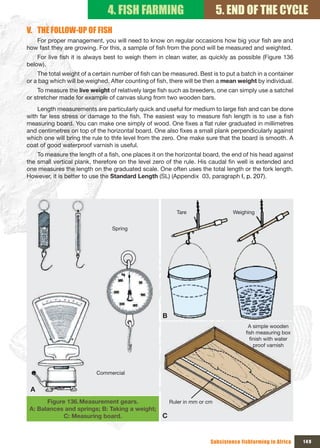

![4. FISH FARMING 5. END OF THE CYCLE

Round

Square or rectangular

Half-round

Handle

Frame

Bag

Photo R. Dip net (Guinea) [© Y. Fermon].

9 A handle, made from metal or wood and

0.20 to 1.50 m long, depending on the use of the Figure 124. Different types of dip nets.

dip net.

The size and shape of dip nets vary greatly. It is important to keep the following guidelines in

mind. Handle live fish using dip nets with relatively shallow bags. Their depth should not exceed 25

to 35 cm. One will have to select a size suitable for the size of fish to be handled.

I.5. TRAPS

There are many different kinds of traps commonly used when fishing in lakes and rivers in the

wild. It might be the case to catch broods-

tock or associated species as catfish.

Certain kinds may be useful for simple and

regular harvest of food fish without distur-

bing the rest of the pond stock.

These traps are usually made with

wood, plastic pipe, bamboo or wire

frames, with netting, bamboo slats or wire

mesh surfaces.

Opening: 25 to 30 cm

There are two main types (Figure 125 Length: 80 to 100 cm

opposite and Photo S, p. 136):

9 Pot traps, which are usually bai-

ted and have a funnel-shaped entrance

through which fish can enter but have dif-

ficulty escaping from; and

9 Bag or chamber traps, which

usually have a guide net that leads the fish

into a chamber and have a V-shaped en-

trance that keeps the fish from escaping. Figure 125. Differents types of local traps.

Subsistence fishfarming in Africa 135](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-153-320.jpg)

![Photo S. Traps. On left and up on right,

traditionnal trap (Liberia); Down on

right, grid trap full of tilapia (Ehiopia)

[© Y. Fermon].

I.6. HANDLINE AND HOOKS

One of the easiest methods to capture broodstock is just with a fishing handline. It is a selective

gear which allow to capture and to maintain in life without problem fish like the tilapia.

It will however be a question of using as much as possible hooks without barb.

II. THE TRANSPORT OF LIVE FISH

Transport of live fish is common practice on many fish farms, used for example:

Ö After harvest of fish in wild;

Ö To take fish to short-term live storage.

The duration of transport varies according to the distance to be covered:

9 From the river, transport time is usually longer, varying from a few hours to one or two days;

9 On the farm, transport time is usually very short (a few minutes) to short (up to 30 minutes).

There exist certain basic principles governing the transport of alive fish:

Ö Live fish are generally transported in water. The quality of this water changes progressively du-

ring transport. Major changes occur in the concentration of the chemicals.

¾ Dissolved oxygen (DO) is mainly used by fish for their respiration. Bacterial activity and oxyda-

tion processes will also use oxygen in the presence of organic matter.

9 The oxygen consumption increase with the temperature.

9 The DO consumption by small fish for 1 kg is higher than fish a larger size.

136 Subsistence fishfarming in Africa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-154-320.jpg)

![night or early in the morning. In the same way,

direct solar light will be avoided and it will be

preferably to place the containers in the shade.

The containers can bec over with bags or wet

tissue to increase the cooling effect of evapo-

ration

One should not feed fish during transport.

As much as possible, the water of trans-

port will be replaced by better oxygenated and

fresher water, during long stops, if the fish seem

disturbed or start to come to water surface to

breathe, instead of remaining calmly at the bot-

tom or when transport lasts more than 24 hours

without additional oxygen contribution. If ne-

cessary, the quantity of oxygen in water can be

increased by agitating water with the hand.

The density of fish should not be too high

to avoid a too strong oxygen uptake. For a bag

of ½ liter, 3 or 4 fish of 2 cm but only one of

8 cm must be put in. Moreover, for fish suba-

dultes and adults, wounds can be caused by the

contacts and may result in the death of a fish.

As soon as a fish died in a bag or a contai-

ner, it should be removed quickly.

For the release of fish in water, one will let

the container soak in order to reduce the va-

riation in temperature between the water of the

bag and the water of the pond. Then, one will

put water of the pond little by little in the contai-

ner to finish the acclimatization of fish before

releasing them.

Photo T. Fish packing in plastic bags

(Guinea, (Ehiopia)

[© Y. Fermon, © É. Bezault].

Regulator, valve

and air cylinder Deflate bag

and close it

Tie

around Pull

tube tube

Tube Air Air

Water Water + Water +

Water + air Water + air

Fish Fish

+ fish + fish

Figure 126. Fish packing in plastic bags.

138 Subsistence fishfarming in Africa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-156-320.jpg)

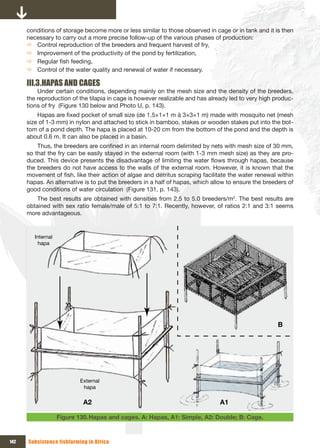

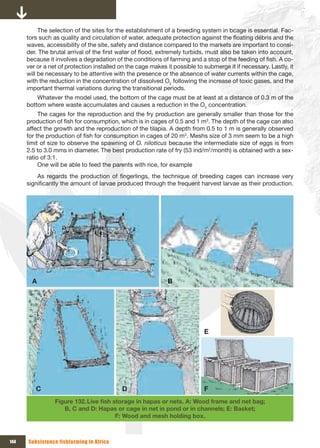

![4. FISH FARMING 5. END OF THE CYCLE

A B C

Figure 131. Differents systems of reproduction of tilapia in hapas and cages. A: Simple;

B: Double with breeders in the middle; C: Breeders in one half.

One of the advantages of the use of the system hapas is the facility of control of the spawnings

and recovery of fry, each unit being easily handle by one or two people maximum. One can also get

the fry every day with hand net. A good harvest interval will be from 10 to 14 days for females of one

to two years old.

The cages generally consist of a rigid framework of wood made support or of metal equipped

with a synthetic net delimiting a volume of water and equipped with a system of floating attached to

the upper framework or supported by stakes inserted in the lakes or river at a shallow depth.

Photo U. Hapas in ponds (Ghana) [© É. Bezault].

Subsistence fishfarming in Africa 143](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-161-320.jpg)

![4. FISH FARMING 5. END OF THE CYCLE

These harvests, repeated and complete, are all the more effective as they do not require draining of

the pond, nor fishings with the seine, and thus limit the losses of offspring regularly observed at the

time of these operations. Moreover, the system with double net reduces the cannibalism exerted by

the adults, thus increasing the number of larvae produced by female. To note that cages and hapas

can be used to store fish collected during the draining of the ponds of production.

Consequently, in fishfarming production, it seems advisable to install parents with the

density of 4 ind/m2, of 1.5 to 2 years old, with males slightly larger than the females with a sex-

ratio of 1 male for 3 females.

These cages or hapas can be put directly in the water supply channe or other points where they

will be protected. They can be used for several ends:

Ö Production of fingerlings

Ö Storage of fingerlings collected in the wild

Ö Storage of the associated species after captures in the wild

Ö Storage of fish after draining of the ponds.

One will be able to also make use of small nets or others materials for that (Figure 132, p. 144).

III.4. THE OTHER STRUCTURES

There exist other structures like the concrete basins or aquariums to produce fingerlings. Howe-

ver, these structures are rather indicated for large production in commercial-type operations. They

require costs and technical much more higher and expensive (Photo V below).

The basins in masonry or breeze blocks generally have a elongated shape making it possible to

maintain a good circulation water.

The aquariums must be of big size (minimum 200 l for tilapia).

Photo V. Concrete basins and aquariums (Ghana) [© Y. Fermon].

Subsistence fishfarming in Africa 145](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-163-320.jpg)

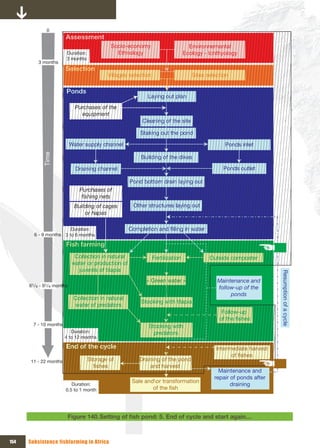

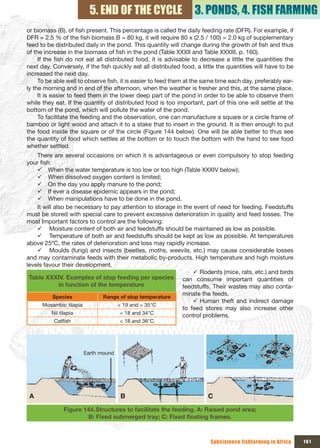

![5. END OF THE CYCLE 3. PONDS, 4. FISH FARMING

III. THE MANAGEMENT OF PONDS

Proper management consists of monitoring the fish ponds regularly, keeping good records and

planning ahead for the operation of the farm. On this basis, for example one can decide when to

fertilize your ponds.

III.1. FISH STOCKS AND USEFUL INDICES FOR MONITORING

It is important to monitor the fish stocks closely. For this it is necessary first to learn about the va-

rious indices or parameters which are commonly used to measure and compare the performances

of various stocks in fish farms such as their growth, production and survival.

The following terms are used to describe the size of a fish stock:

9 Initial fish stock which is the certain number and weight of fish stocked into the pond at the

beginning of the production cycle. Two parameters then are:

¾ Stocking rate which is the average number or weight of fish per unit area such as 2 fish/

m2, 2 kg fish/m2, or 200 kg/ha;

¾ Initial biomass which is the total weight of fish stocked into a specified pond such as

100 kg in Pond X.

9 Fish stock during production cycle which is the certain number and weight of fish present

in the pond. They are growing, although some of them may disappear, either escaping from the pond

or dying. An important parameter is then:

¾ Biomass present which is, on a certain day, the total weight of fish present in a pond.

9 Final fish stock which is the certain number or weight of fish at the end of the production

cycle, similarly:

¾ Final biomass which is the total weight of fish present at final harvest.

Concerning the changes in a fish stock at harvest or over a period of time:

Ö Output or crop weight is the total weight of fish harvested from the pond.

Ö Production is the increase in total weight that has taken place during a specified period. It is

the difference between the biomass at the end and the biomass at the beginning of the period. For

example, for a stocking of 55 kg, and a weight measured after 30 days of 75 kg, 75 - 55 = 20 kg.

Ö Yield is the production expressed per unit area. For example if 20 kg were produced in a 500 m2

pond, the yield during the period was 20 / 500 = 0.040 kg/m2 = 4 kg/100 m2 or 400 kg/ha.

Ö Production rate is the production expressed per unit of time (day, month, year, etc). For example,

if 20 kg were produced in 30 days, the daily production rate would be 20 / 30 = 0.66 kg/day.

Ö Equivalent production rate is the yield expressed per unit of time, usually per day or per year

= 365 days. It enables to compare productions obtained in various periods. For example 400 kg/ha

produced in 30 days are equivalent to (400 x 365) / 30 = 4 866.7 kg/ha/year. It may be also useful

to indicate the average daily production rate, which in this case is 4 866.7 / 365 = 13.3 kg/ha/day or

1.33 g/m2/day.

Ö Survival rate is the percentage of fish still present in the pond at the end of a period of time. It

should be as close as possible to 100 percent. For example, if there were 1200 fish at the beginning

of the period and 1 175 fish at the end, the survival rate during that period was

[(1 175 x 100) / 1200] = 97.9%; mortality rate was 100 - 97.9 = 2.1%.

A stock of fish is made of individuals. One can point out here the measurements taken on the

individuals for the follow-up of the pond (Chapter 09 paragraph V, p. 149).

Ö The average weight (g) obtained by dividing the biomass (g) by the total number of fish present.

Ö Average growth (g), i.e. increase in the average weight during one period of time given. It is

about the difference between the average weight at the beginning and the end of the period.

Ö Average growth rate, i.e. the growth (g) expressed per unit of time, generally a day. One speaks

then about daily growth rate, obtained by dividing the growth for one period given by the duration of

this period into days. It is calculated either for one period determined during the operating cycle, or

for the totality of this cycle.

Subsistence fishfarming in Africa 167](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-185-320.jpg)

![Example: A pond (312 m²) have been stocking with 680 fish of an initial biomass of 5.6 kg. At the

end of the cycle of production (149 days), the harvest was of 43.8 kg for 450 fish. So:

Pond production = 43.8 - 5.6 = 38.2 kg

Yield = 38.2 / 312 = 12.24 kg/100 m2

Production rate = 38.2 / 149 = 0.26 kg/day

Equivalent production rate = (12.24 x 365) / 149 = 30 kg/100 m2/year

Survival rate = [(450 x 100) / 680] = 66%

Mortality rate = 100 – 66 = 34%

Initial average weight of the fish was of 5600 / 680 = 8.2 g,

and final average weight of 43800 / 450 = 97.3 g.

So, it is:

Average growth during the cycle of production = 97.3 – 8.2 = 89.1 g

Daily groqth rate = 89.1 / 149 = 0.6 g/day.

III.2. THE ExPECTED YIELDS

Yields depend on the species used. However, one can give an estimate of the expected weight

per pond, depending on the species.

Let us consider a pond of 400 m2 containing Nile tilapia (polyculture with the African catfish

Clarias gariepinus), of weight to loading ranging between 5 and 10 g for the two species. At the end

of 7 months of extensive farming (fish given up with themselves, without any contribution), one can

expect a production of approximately 30 kg (either in the 750 kg/ha/an). For the same duration in a

little less extensive (more or less fertilized pond), the annual production will vary from 50 to 100 kg,

that is to say the equivalent from 1.2 to 2.5 tonnes/ha/an. That will go up to 10 tonnes/ha/an in far-

ming with a predator, that is to say 150 kg per pond of 400 m2 over 6 months.

In polyculture which associates Heterotis niloticus and Heterobranchus isopterus, the juveniles

of H. isopterus are introduced with the maximum density of 20 individuals per are into the ponds of

production of tilapia. These systems produce yields of about 4 to 15 t/ha/an, according to the level

of fertilizer contribution.

One can thus obtain 150 kg of fish for a pond of 100 m2 per year, i.e. approximately 12 kg per

month for 100 m2 of pond. For a small pond of 200 m2, which is the minimum, one will be able to thus

have approximately 24 kg per month of fish, that is to say 0.8 kg per day.

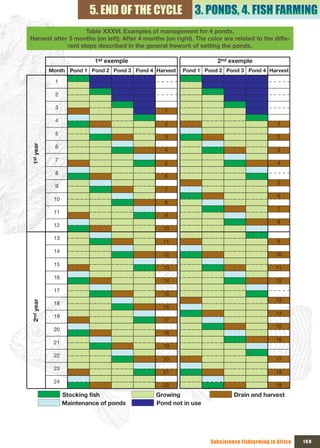

III.3. THE MANAGEMENT OF HARVESTS

The management of harvests will depend on the mode of approach. But in most cases, the vil-

lagers will have by themselves to regulate this aspect. This management will depend on the quantity

of ponds, but it seems adequate to have at least 3 ponds to ensure a quasi monthly harvest with fish

of consumable size.

If one puts fry in different ponds at different times of the year, one will be able to harvest them

at different periods also and, thus, a quantity not too important of fish at the same time. One will be

able to fish all the year.

If there are 4 ponds and a good supply of fingerlings, it can be stocked in each pond at different

month of the year and harvest the pond every 3 to 6 months later according to the size at which

fish seem consumables (Table XXXVI, p. 169). Indeed, depending on location, fish of 60 to 80 g will be

consumed and a tilapia can reach this size in 3 months. The duration and the time of growth will also

depend on the follow-up of growth.

By estimating 4 ponds of 400 m2, which can produce up to 50 kg per month by pond, one will be

able to produce up to 500 kg per year. In a country where the fish is sold to 5 US$/kg, that will make

168 Subsistence fishfarming in Africa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-186-320.jpg)

![Glossary

A B

Abiotic: Physical factor that influences the de- Bacteria: Very small unicellular organism

velopment and / or survival of an organism. growing in colonies often large and unable

Abundance: Quantitative parameter used to to produce components of carbon through

describe a population. The enumeration of photosynthesis; mainly responsible of rot-

a plant or animal population, is generally ting vegetable matter and dead animals.

impossible, hence the use of indicators. Benchmark: see Point, reference

By extension, abundance means a num- Benthos: Groups of vegetable and animals or-

ber of individuals reported to a unit of time ganisms in or on the surface layer of the

or area, within a given population, recruit- bottom of a pond. Associated term: ben-

ment, stock, reported to a unit of time or thic. Opposite: pelagos.

area.

Bicarbonates: Acid salts of carbonic acid (see

Amino acid: Class of organic components carbonate) solution in water, they contain

containing carbon, hydrogen and oxygen, the ion HCO3 as calcium bicarbonate

associated in large numbers, they are pro- Ca(HCO3)2 for example.

teins, some of them play an essential role in

fish production. Bioaccumulation: Catch of substances - e.g.

heavy metals or chlorinated hydrocarbons

Aerobic: Condition or process in which ga- - resulting in high concentrations of these

seous oxygen is present or necessary. substances in aquatic organisms.

Aerobic organisms obtain their energy for

growth of aerobic respiration. Biocenose: Group plants and animal forming

a natural community, which is determined

Anaerobic: Sayd for conditions or processes by the environment or the local ecosystem.

where gas oxygen is not present or are not

necessary. Biodiversity: Variation among living organisms

from all sources including, inter alia, terres-

Anoxic: Characterized by the absence of oxy- trial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems

gen. In a anoxic environment, the mainte- and the ecological complexes of which

nance of aerobic respiration is impossible, they are part: this includes diversity within

consequently, the life is limited to the pre- species, between species and ecosystem.

sence of organizations whose metabolism

is ensured by other mechanisms (fermen- Bioethics: Part of morality concerning research

tation, anaerobic breathing like the sulfato- on life and its uses.

reduction, bacterial photosynthesis…). Biomass: (a) Total live weight of a group (or

Aquaculture: Commonly termed ‘fish farming’ stock) of living organisms (e.g. fish, plan-

but broadly the commercial growing of kton) or of a definite part of this group

marine or freshwater animals and plants in (e.g. breeders) present in a water surface,

water. The farming of aquatic organisms, at a given time. [Syn.: stock present].

including fish, mollusks and aquatic plants, (b) Quantitative estimate of the mass of the

i.e., some form of intervention in the rearing organisms constituting whole or part of a

process, such as stocking, feeding, pro- population, or another unit given, or contai-

tection from predators, fertilizing of water, ned in a surface given for a given period.

etc. Farming implies individual or corporate Expressed in terms of volume, mass (live

ownership of the farmed organisms. weight, dead weight, dry weight or ashes-

off weight), or of energy (joules, calories).

Aufwuchs: German term indicating the layer of [Syn.: charge].

algae adhering on rocks.

Subsistence fishfarming in Africa 179](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-197-320.jpg)

![Equidistance of the level lines: Difference in nity, through which energy is transferred by

rise between two close level lines. food way. Energy enters the food chain by

Ethology: Animal behavior science. the fixation by the primary producers (green

plants for the major part). It passes then to

Eutrophic: Rich in nutrients, phosynthetic pro- the herbivores (primary consumers) then

ductive and often deficient in oxygen under to the carnivores (secondaries and tertiary

warm weather. consumers). The nutritive elements are then

Eutrophication: The enrichment of a water recycled towards the primary production by

body in nutritive elements, in a natural or the detritivores.

artificial way, characterized by wide plank- Fry: A young fish at the post-larval stage. May

tonique blooms and a subsequent reduction include all fish stages from hatching to fin-

in the dissolved oxygen content. gerling. An advanced fry is any young fish

Extrusion: Process of transformation of food from the start of exogenous feeding after

material is subjected for a very short time the yolk is absorbed while a sac fry is from

(20 to 60 s) at high temperatures (100 to hatching to yolk sac absorption.

200°C) at high pressures (50 to 150 bars),

and a very intense shear . G

F Gauge: Model of wood being used to give the

wanted form, for example with a channel or

Fatty-acid: Formed lipid of a more or less long a dike.

hydrocarbon chain comprising a carboxyl Gamete: Reproductive cell of a male or female

group (-COOH) at an end and a methyl living organism.

group (-CH3) at the other end.

Gene: ÉlémentBasic element of the genetic in-

Fecundity: In general, potential reproductive heritance contained in the chromosomes.

capacity of an organism or population, ex-

pressed by the number of eggs (or offspring) Genetics: Science for the purpose of studying

produced during each reproductive cycle. issues concerning the transmission of traits

from parents to offspring in living beings.

Relative fecundity: Number of eggs per

unit fresh weight. Genotype: Genetic structure of an organism at

the locus or loci controlling a given pheno-

Absolute fecundity: Total number of eggs type. An organism is homozygote or hetero-

in a female. zygote at each of the loci.

Feedingstuff, supplementary: Food distribu- Gonado-somatic ratio: Ratio of the weight of

ted in addition to food presents naturally. the gonades to the total live weight (or of

Feedingstuff, composed: Food with several the total live weight to the weight of the go-

ingredients of vegetable or animal origin nades), usually expressed like a percentage.

in their natural, fresh or preserved state,

or of derivative products of their industrial H

transformation, or of organic or inorganic

substances, containing or not additives, Halieutic: Science of the exploitation of the

intended for an oral food in the shape of a aquatic alive resources.

complete feedingstuff. Herbivore: Animal which feed mainly on plants.

Fermentation: The anaerobic degradation of or- Hormone: Chemical substance produced in

ganic substances under enzymatic control. part of an organism and generally conveyed

Fingerling: Term without rigorous definition; by blood in another part of this organism,

says for young fish starting from advanced where it has a specific effect.

fry until the one year age starting from the Humus: Decomposed organic matter present in

hatching (independently of the size). [Syn.: organic manures, composts or grounds, in

juvenile]. which the majority of the nutritive elements

Food chain: Simplistic concept referring to the are available for fertilization.

sequential series of organisms, pertaining Hybridization: Fecundation of a female of a

to successive trophic levels of a commu- species by the male of a different species.

Subsistence fishfarming in Africa 181](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-199-320.jpg)

![Hydraulics: Relating to water, the action or the components (fats and similar substances)

energy utilization related to its movements. largely present in the living organisms; the

lipids have two principal functions: energy

I source and source of certain food compo-

nents (fatty-acids) essential to the growth

Ichtyology: The study of fish.

and survival.

Ichtyophagous: Animal feeding mainly on fish.

[Syn.: piscivorous]. M

Indigenous: Native of a country or a place. Macrophagous: Living organism which feeds

[Syn.: native]. on preys having a size larger than that of its

Irrigation sluice: Work derivation placed on a mouth. Opposite: microphagous.

feeder canal to divert its flow into two (type Macrophyte: Relatively large vascular plant

in T) or in three (type in X) parts, or to in- by comparison with the microscopic phy-

crease the water level in a section of the toplankton and the filamentous algae. The

channel, or to control the water supply with basic structure of a aquatic macrophyte is

height of the water supply of a pond. visible with the eye.

J Maturation: Process of evolution of the go-

nades towards maturity.

Juvenile: Stage of the young organism before

Metamorphosis: All changes characterizing

the adult state. [Syn.: fingerling].

the passage of the larval state in a juve-

K nile or adult state for some animals. These

changes concern at the same time the form

and physiology and is often accompanied

L by a change of the type of habitat.

Larva, larvae: Specific stage to various ani- Mesocosme: Ecosystem isolated in a more or

mals, which is between the time of hatching less large enclosure from a volume from wa-

and the passage at the juvenile/adult form ter from one to 10 000 m3. Mainly used for

by metamorphosis. the production of alive preys in earthenware

Level: see Elevation. jars, basins, pockets plastic, ponds and en-

closure.

Level or reference plan: Level or plan used on

several occasions during a particular topo- Metabolism: Physical and chemical processes

graphical survey and by report to which the by which the food is transformed into com-

raised lines or points are defined. plex matter, the complex substances are

decomposed into simple substances and

Levelling: Operation consisting in measuring energy which is available for the organism.

differences in level in various points in the

ground with topographical survey. Milt: Mass genital products. Said also for the

sperm of fish.

Life cycle: The sequence of the stages of the

development of an individual, since the Monoculture: Farming or culture of only one

stage egg until death. species of organisms at the same time.

Line of saturation: Upper limit of the wetland in Mulch: Made non-dense cover organic residues

an earthen dike partially submerged. (for example cut grass, straw, sheets) which

one spreads on the surface of the ground,

Line of sight: Imaginary line from the eye of the mainly to preserve moisture and to prevent

observer and directed towards a fixed point, bad grasses from pushing.

it is always a straight line, also called «line

of sight.» Mulching: Placement of a layer of vegetable

matter, in order to protect young plantations

Limnology: The study of the lakes, ponds and (see Mulch).

other plans of stagnant fresh water and their

biotic associations. N

Lipid: One of the main categories of organic

Nekton: Animal whose swim actively in a pond;

182 Subsistence fishfarming in Africa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-200-320.jpg)

![Photosynthesis: (a) Process by which the green of speed appearing when water moves

plants containing chlorophyl transform solar through a pipe or any other hydraulic work.

energy into chemical energy, by producing Probiotic: All the bacteria, yeasts or algae

organic matters starting from minerals. (b) added to some food products and which

Mainly production of composed of carbon help with the digestion of fibers, stimulate

starting from carbonic gas CO2 and water, the immune system and prevent or treat

with oxygen release. gastro-enteritis.

Phylogeny: Characterize the evolutionary his- Protein: Composed organic whose molecule is

tory of the groups of living organisms, in of important size and of which the structure

opposition to ontogeny which characterizes complex, made by one or more chains of

the history of the development of the indivi- amino-acids; essential to the organism and

dual. Associated term: phylogenetic. the functioning of all the living organisms;

Phytobenthos: Benthic flora. The food proteins are essential for all the

Phytoplankton: Unicellular algae living in sus- animals, playing a part of reconstituting tis-

pension in the water mass. Vegetable com- sue or energy source.

ponent of the plankton. Protozoa: Very small unicellular animal orga-

Piscivorous: Animal feeding mainly on fish. nisms, living sometimes in colonies.

[Syn.: ichthyophagous].

Q

Plan: Imaginary plane surface; any straight line

connecting two unspecified points of a plan

is located entirely in this plan. R

Plankton: All organisms of very small size, ei- Raceway: Basin with the shape of circuit used

ther plants (phytoplankton), or animals (zoo- for the farming in eclosery.

plankton), which live in suspension in water. Ration: Total quantity of food provided to an

Planktivorous: Animal feeding on phyto- and/or animal during one 24 hours period.

of zooplankton. Recruitment: Process of integration of one new

Plasticity: (a) Capacity which has a soil to be- generation to the global population. By ex-

come deformed without breaking and to tension, the new class of juveniles itself.

remain deformed even when the deforming Repopulation: Action to released in large num-

force does not act any more. (b) Ability of ber in the natural environment of the orga-

a trait in an organism to adapt to a given nisms produced in eclosery, with an aim of

environment. reconstitution of impoverished stocks.

Point, lost: Temporary topographic point of Resilience: Refer to the aptitude of an ecologi-

reference which one carries out the survey cal system or a system of subsistence to be

between two definite points; It is not used restored after tensions and shocks.

any more when the statements necessary

Respiration: Process by which a living orga-

were made.

nism, plants or animal, combines oxygen

Point, reference: Point usually fixes identified and organic matter, releasing from energy,

on the ground by a reference mark placed at carbonic gas (CO2) and other products.

the end of a line of sight. (see Benchmark). [Syn.: breathing].

Polyculture: The farming of at least two non- Rhizome: Thick and horizontal stem, generally

competitive species in the same unit of far- underground, which emits growths to the

ming. top and of the roots downwards.

Porosity: Free space between the particles or

the lumps ones in the soil. S

Post-larva: Stage which follows that of the larva Scrubbing: In-depth migration of the soluble

immediately and presents some characters substances or colloids in the interstices of

of the juveniles one. the ground.

Pressure loss: The pressure loss is due for Sedentary: Who moves little and remains in his

example to the friction or the shifting habitat.

184 Subsistence fishfarming in Africa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-202-320.jpg)

![II.3.2. MOUTHBROODING

The eggs are larger but relatively fewer than at the substrates spawners. Most of the time, the

spawn is carried out on a substrate, often prepared by the male. However, for some pelagic species,

the spawn can take place in full water. In general, they are polygamous species. The males form a

territory which the females come to visit. One distinguishes three main categories of oral incubation:

9 Maternal incubation is the most frequent system. The spawn takes place on a substrate,

and the non-adhesive eggs, laid singy or by small groups, are taken quickly in the mouth by the

female. The male deposits its sperm at the time when the female collects eggs or then fertilizes

them in the mouth. Mouthbrooding continues until the juveniles are entirely independent. In certain

cases, the female release them periodically to feed then takes them in the mouth. It is the case of

all Haplochromines and the genus Oreochromis. The females can incubate at the same time eggs

fertilized by several partners.

9 Paternal incubation is practiced by some species only. It is the case for Sarotherodon

melanotheron.

9 Biparental incubation is also a rare case among Cichlidae. At the majority of Chromidotila-

pines the two parents share the fry. There exist also species at which the female begins incubation

then the male takes over: it is the case of Cichlidae gobies of lake Tanganyika.

At the oral incubators, often, the males stayed on a zone of nesting at a shallow depth and on

a movable substrate (gravel, sand, clay). Each male showing a characteristic color patterns delimits

and defends a territory and arranges a nest, where it will try to attract and retain a ripe female. The

shape and the size of the nest vary according to the species and even according to the popula-

tions within the same species (Figure 170 below). It is often about an arena social organization of

reproduction. The females which live in band near the surface of reproduction come only for briefs

stays on the arenas. Going from one territory to another, they are courted by successive males until

the moment when, stopping above the cup of a nest, they form a transitory couple. After a parade

of sexual synchronization (Figure 171, p. 220), the

female deposits a batch of eggs, the male im-

mediately fertilizes them by injecting its sperm

on eggs in suspension in water, then the female

is turned over and takes them in the mouth to

incubate them. This very short operation can

be started again, either with the same male, or

with another male in a nearby territory. At Haplo-

chromines, the anal fins present a spot mimicry

an egg to lure the females. It is about succes-

sive polygyny and polyandry. Finally, the female

moves away from the arena where the males re-

main confined and carries in mouth the fertilized

eggs which it will incubate in sheltered zones. Photo W. Nests of Tilapia zillii (Liberia)

[© Y. Fermon].

A B

Figure 170. Nest of A: Oreochromis niloticus; B: Oreochromis macrochir.

Subsistence fishfarming in Africa 219](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-237-320.jpg)

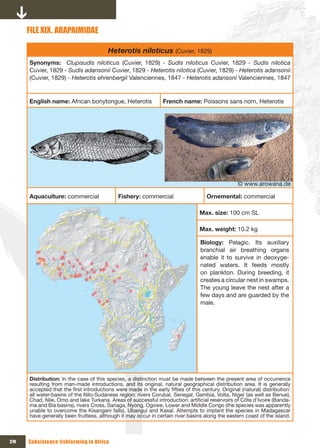

![■ CHRYSICHTHYS AURATUS

The biology of C. auratus seems very close to that of C. maurus but with a definitely lower

growth. This species is not of thus any fishfarming interest.

■ CHRYSICHTHYS NIGRODIGITATUS

In wild, C. nigrodigitatus reaches 18 cm (fork length) in one year, 24 cm in two years and 30 cm

in three years. Studies showed that raised out of basin, it spent eleven months to pass from 15 g

(11 cm) to 250 g (26 cm). In a wild state, C. nigrodigitatus in general reproduces from the size of 33

cm (3 years old) with a behavior similar to that of C. maurus (search for receptacle of spawn by the

pair). The relative fecundity of this species is close to that of C. maurus. It is given, on mean, a value

of 15 ovocytes per g of weight of female, with extreme values of 6 and 24.

The hatching intervenes 4 to 5 days after at the temperature of 29 - 30°C by giving larvae from

25 to 30 mg equipped with an important vitelline bag which reabsorbs gradually in ten days. They

reach 350 - 400 g into 8 to 10 months.

There exists in the adult females a progressive and synchronous development of the gonads cor-

responding to the reproductive season well marked. The spawning begin at the end of August and

their frequency is maximum between September and October (more than 50%). One observes then

a fall around at the end of November and the activity of spawning is completed in December. Howe-

ver, it should be noted that if the majority of the spawnings is located regularly between September

and November, the annual maximum moves appreciably according to the years.

A

B

C

Photo X. Claroteidae. A: Chrysichthys nigrodigitatus [© Planet Catfish];

B: C. maurus [© Teigler - Fishbase];

Auchenoglanididae. C: Auchenoglanis occidentalis [© Planet Catfish].

232 Subsistence fishfarming in Africa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-250-320.jpg)

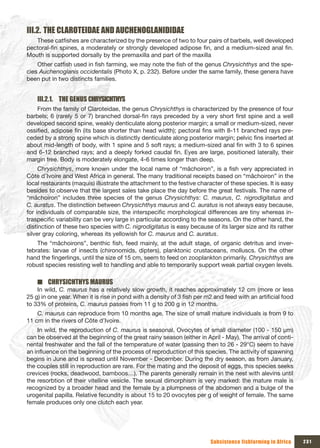

![III.2.2. THE GENUS AUCHENOGLANIS

From the family of the Auchenoglanididae, the genus Auchenoglanis is characterized by its

slightly elongate body, three pairs of barbels (one maxillary and two mandibular) and the position of

the anterior nostril on upper lip. Dorsal fin with 7 branched rays preceded by 2 spines, the first small,

the second strong and denticulate; adipose fin originating shortly behind the dorsal; pectoral fins

with 9 branched rays preceded by a strong spine; pelvic fins well developed, with 6 rays, 5 of them

branched; anal fin medium-sized, with 6-8 branched rays; caudal fin emarginate.

This species has been tested in Côte d’Ivoire at Bouaké. Growth rates have been quite low and

the test was not renewed.

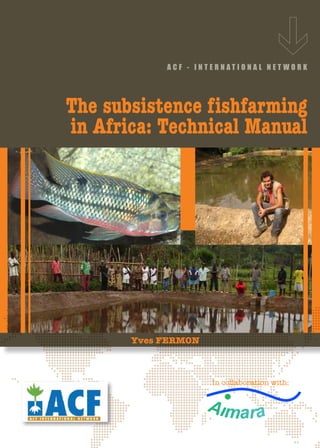

III.3. THE SCHILBEIDAE

The Schilbeidae (a catfish family found in Africa and Asia) are characterized by a dorso-ventrally

flattened head, a rather short abdomen, a laterally compressed caudal region, and an elongate anal

fin (Photo Y below). Dorsal fin is short, sometimes absent. Pectoral fins are provided with a spine (as

also the dorsal fin of most species). Three or four (depending on species) pairs of barbels are found

around mouth. The Schilbeidae are moderately good swimmers with laterally compressed bodies,

as opposed to the majority of bottom-living siluriform fishes which are anguilliform or dorso-ventrally

flattened. Five genera have so far been recognized in Africa: Parailia, Siluranodon, Irvineia, Schilbe

and Pareutropius. The three first genera have only a low economic value because of their small size.

However, some species of the genera Irvineia and Schilbe may reach large size (50 cm or more) are

very appreciated.

For Schilbe mandibularis, the size of the first sexual maturity presents a variation along the river

(upstream, lake and downstream) for the two sexes. It is slightly weaker in the males than in the

females (12.3 cm compared with 14.8 upstream and 14.8 against 18.1 cm downstream). The relative

data with the evolution of sexual maturity and the gonado-somatic ratio reveal a seasonal cycle of

reproduction distinct. The species reproduces in rainy season from April to June then from August

to October. The maximum activity of reproduction occurs from April to June, corresponding to the

peak of pluviometry. The sexual rest occurs during the dry season, from December to March. Ave-

rage relative fecundity reaches 163600 ovocytes per kg of body weight, with a minimum of 15308

ovocytes and a maximum of 584593. The diameter of the ovocyte at the spawn is approximately of

1 mm. A negative effect of the lake environment on certain biological indicators of the reproduction

(size of the first sexual maturity, sex-ratio, average body weight and fecundity) was highlighted. This

influence of the lake could be due to the strong pressure of fishing which is exerted there.

The fish of the genus Schilbe become piscivorous towards 13 - 14 cm TL. They are fish usable

for the control of the populations of tilapia.

III.4. THE MOCHOKIDAE

All representatives of this family have a scaleless body and three pairs of barbels, one maxillary

and two mandibular pairs, except in some rheophilic forms in which the lips are modified into a suc-

king disk. Nasal barbels are absent. First dorsal fin have an anterior spinous ray, adipose fin is large

and sometimes rayed. First pectoral-fin ray is spinous and denticulate. A strong buckler present on

head-nape region. Eleven genera and nearby 180 species are known (Photo Z, p. 234).

Several species of the genus Synodontis can reach a large size (more than 72 cm) and represent

a clear commercial interest. Some could be used as species of complements for polyculture.

Photo Y. Schilbeidae. Schilbe intermedius [© Luc De Vos].

Subsistence fishfarming in Africa 233](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/applicationletter-projectdevelopmentintern-kenya-110128054301-phpapp02/85/Application-letter-project-development-intern-kenya-251-320.jpg)

![A

B

Photo Z. Mochokidae. A: Synodontis batensoda [© Mody - Fishbase]

B: Synodontis schall [© Payne - Fishbase].

IV. THE OTHER FAMILIES

Other fish have been tested and needs tests in fishfarming.

IV.1. THE CYPRINIDAE

It is the family of the Carps which are usually used in fishfarming.

The fish of the family Cyprinidae have a body covered with cycloid scales and a head naked. All

rayed fins are well developed, but adipose fin is absent. Mouth is protrusible, lacking teeth. Some-

times one or two pairs of more or less well developed barbels are present. Lower pharyngeal bones

very well developed, are bearing a few teeth aligned in 1-3 rows.

In spite of fish of large size observed in Africa, such as for example of the genera Labeo, Va-