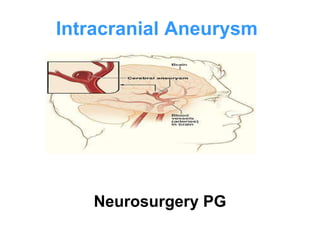

Intracranial aneurysms are focal dilatations of blood vessels in the brain that are prone to rupture and cause subarachnoid hemorrhage. The most common type is saccular aneurysms located at vessel junctions or branch points. Ruptured aneurysms present with sudden severe headache, neck stiffness, nausea/vomiting, and sometimes altered consciousness. Diagnosis is made using CT or MRI of the brain along with CT or catheter angiography. Treatment involves surgery such as clipping or endovascular coiling to prevent further rupture as well as managing complications like vasospasm.