This exploratory case study examined effective methods for faculty without formal writing education to implement a writing-infused curriculum across disciplines. There is a need for this due to gaps in past writing-across-the-curriculum initiatives and students' lack of writing proficiency. While almost all college courses require writing, instructors outside English often have no composition training. The study gathered input from instructors assessing writing in discipline-specific courses and explored current teaching strategies. It addressed gaps in research on writing initiatives at non-traditional universities. The theoretical framework of "teacher-learner community" informed the study, which involved a qualitative survey, classroom observations, and a focus group to identify strategies for faculty to assess student writing without expertise in

![8

literary perspective and not including experience or students’ contextual framework when

teaching writing (Bazerman et al., 2005, p. 20).

Past WAC initiatives provided strategies to students for writing in their major-

specific courses. WAC needs to be expanded to regionally accredited art and design

colleges and universities, such as Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD),

Maryland Institute College of Arts (MICA), and Rhode Island School of Design (RISD).

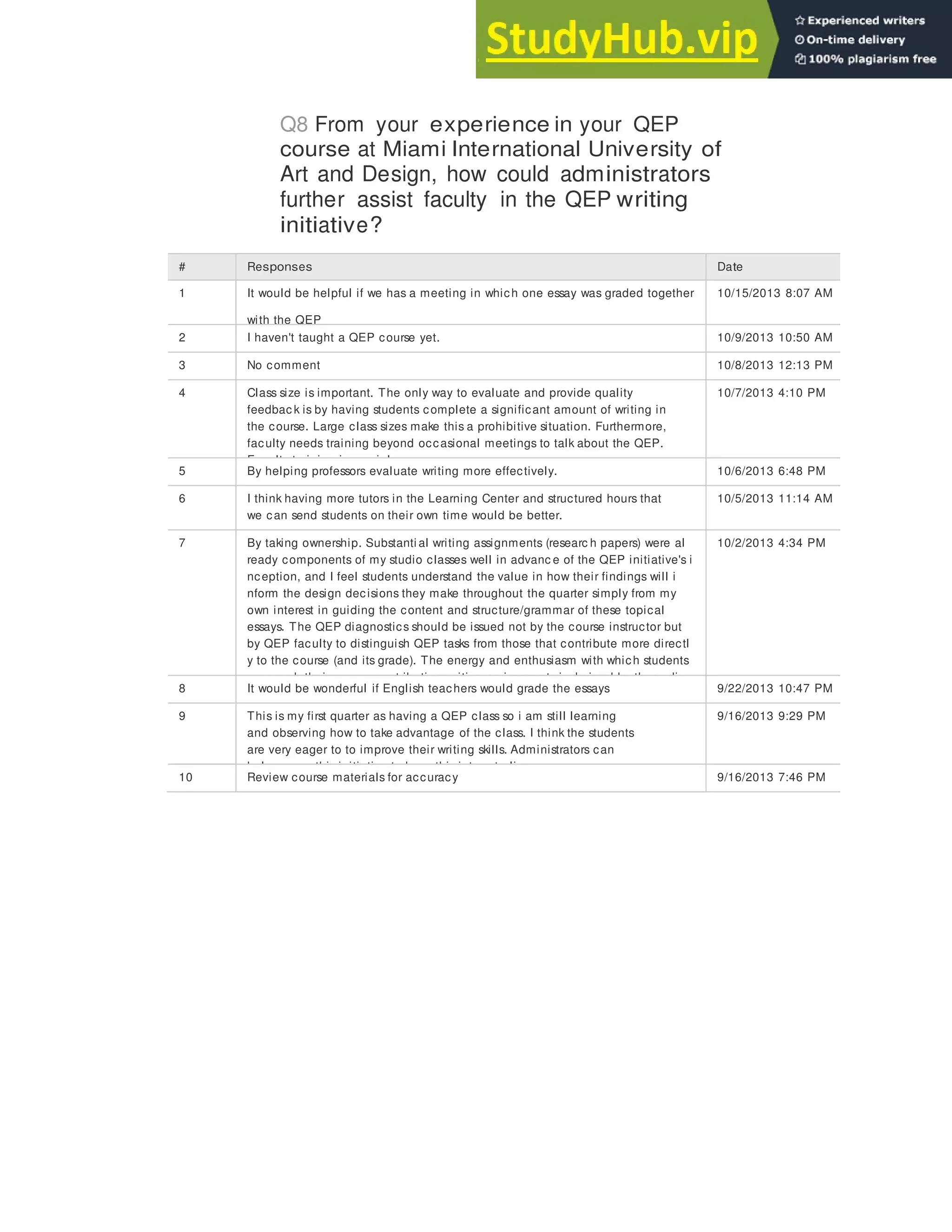

These institutions needed to assess student writing proficiency as a part of the

accreditation process (Mullin, 2008; New England Association of Schools and Colleges:

Commission on Institutions of Higher Education [NEASC-CIHE], 2011; SACSCOC,

2012). Because of the general decline in recent university graduates’ ability to possess

both technical and language skills, they were less likely to procure employment (Mullin,

2008). This may have been a primary reason why traditional and non-traditional

universities, such as Miami International University of Art and Design (MIUAD), have

implemented writing programs that are major-specific to meet the demands of today’s

workforce (Wingate, Andon, & Cogo, 2011).

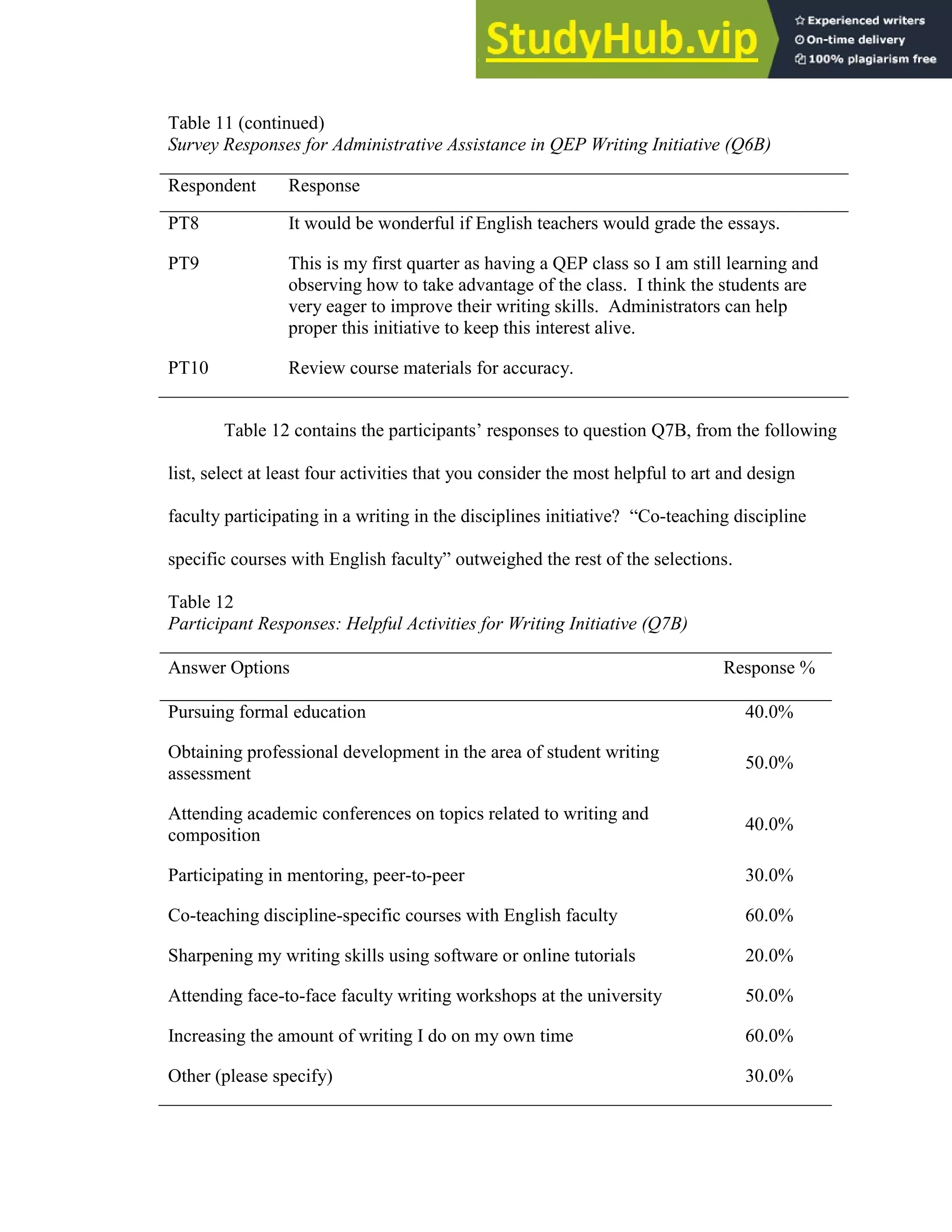

Educational Accreditation

Oral and written communication skills are important components of a college

degree and are required as part of the regional accreditation process. The expectation that

college graduates will be able to speak and write proficiently in English is reflected in

standards set by educational regional accreditation bodies, such as SACSCOC, that

develop guidelines for universities to follow to maintain specific standards for writing

courses.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anexploratorycasestudyfacultyinvolvementindevelopingwriting-infusedcourseswithintheprofessionaldisci-230805195440-0c70ba2a/75/AN-EXPLORATORY-CASE-STUDY-FACULTY-INVOLVEMENT-IN-DEVELOPING-WRITING-INFUSED-COURSES-WITHIN-THE-PROFESSIONAL-DISCIPLINES-18-2048.jpg)

![28

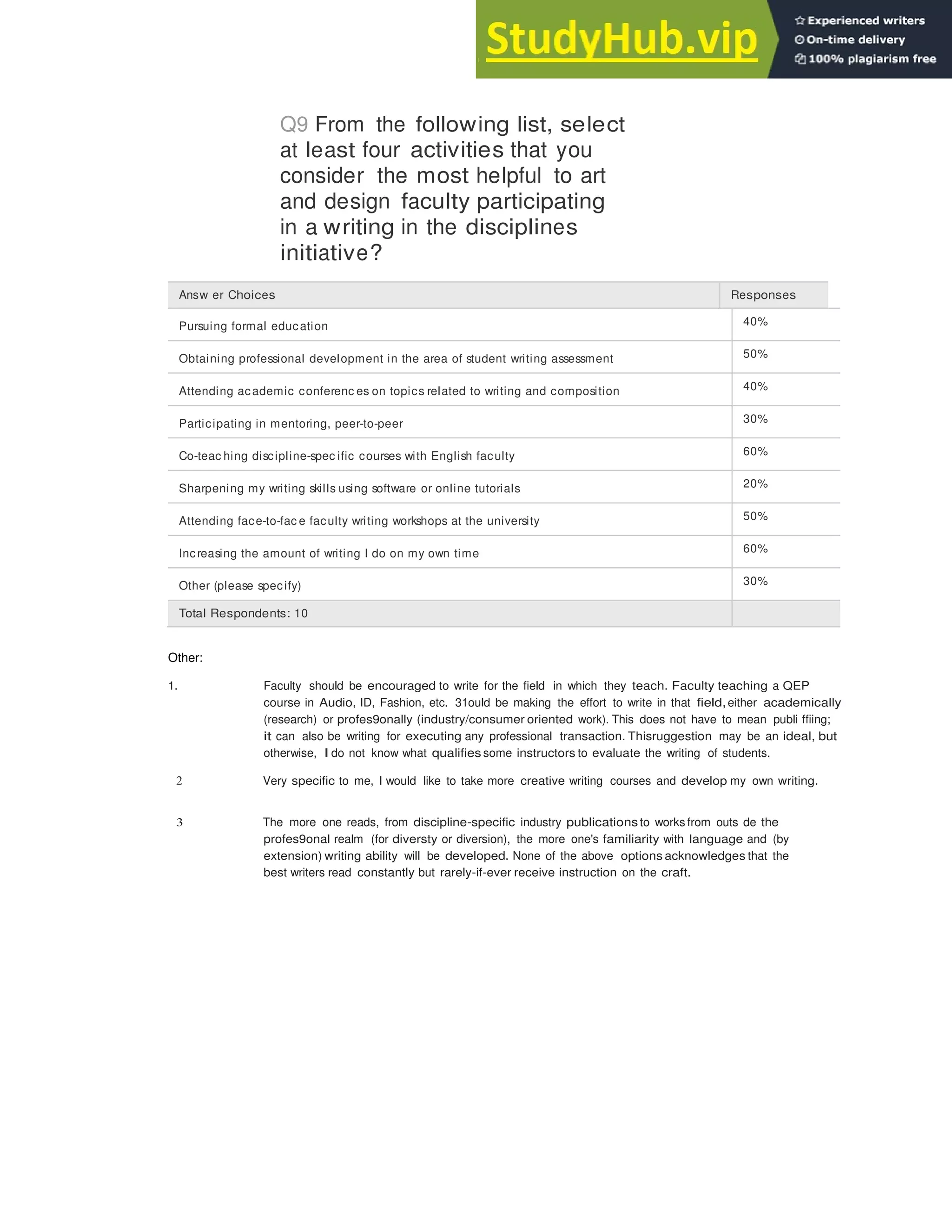

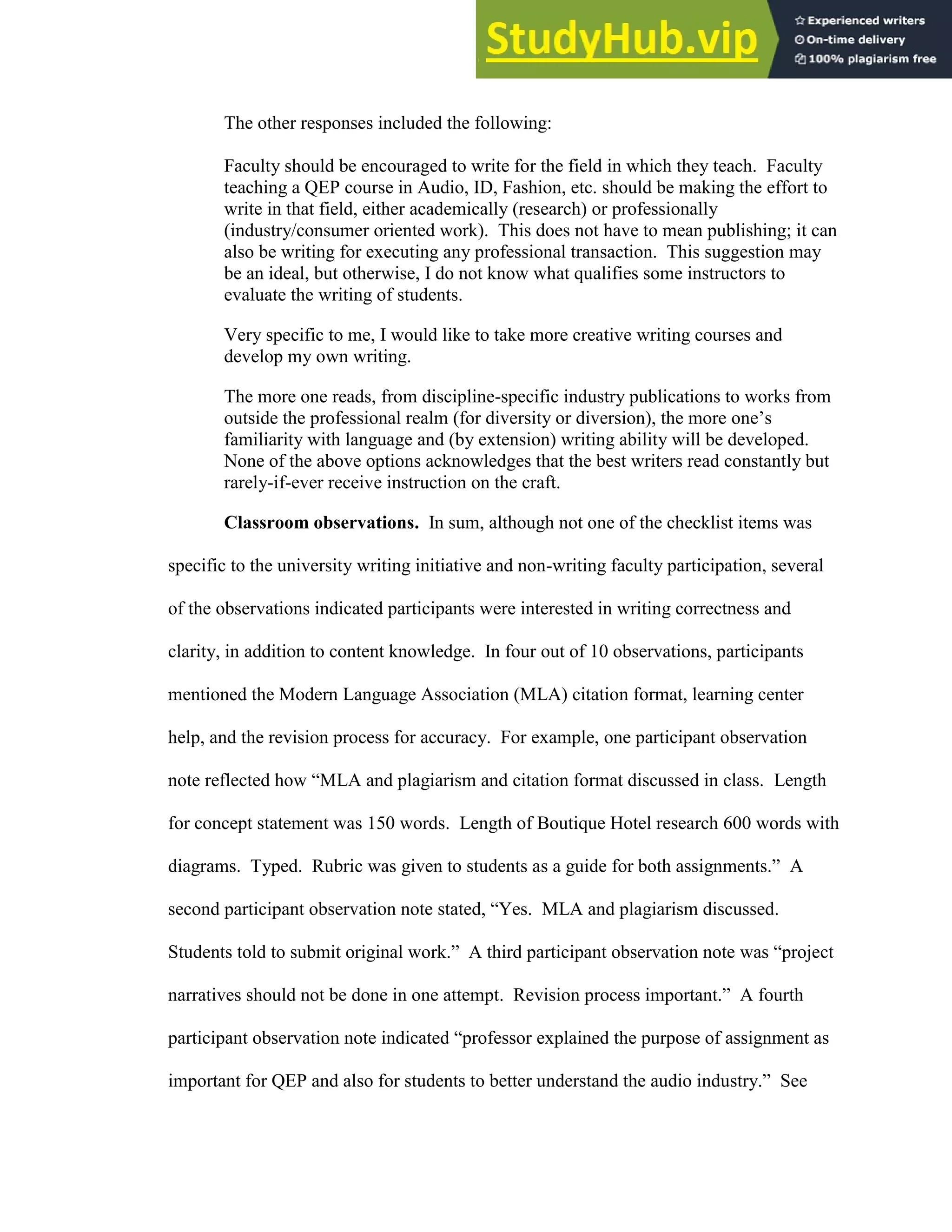

student writing in the disciplines (Altbach et al., 2005; Fernsten & Reda, 2011; McLeod

& Soven, 2000; Perelman, 2011). Over the last 50 years, changes in admission standards,

core curriculum, and regional accreditation standards have triggered the need for faculty

without a formal academic background in the language arts to assess students’ basic

grammar skills and usage within discipline-specific academic situations (Altbach et al.,

2005; Bazerman et al., 2005; Condon & Rutz, 2012; Lucas, 2006; McLeod & Soven,

2000). Over the last 15 years, several other gaps in the teaching of writing, such as

technology, diversity, and curriculum alignment, have become evident and are discussed

in this chapter (Hassel, 2013).

This review of the literature addresses the gaps that exist in research on writing intensive

curriculum in the media arts and design area. This chapter includes an analysis of: (a)

history of infusing writing across the professional disciplines, (b) freshman composition

and general education, (c) writing across the curriculum (WAC), (d) teaching writing

strategies and WAC implementation today, (e) effective strategies for the teaching of

writing, and (f) research gaps in teaching college English

History of Infusing Writing Across the Professional Disciplines

The importance of written and oral communication skills is not a new

phenomenon in higher education. The Yale Report (Yale University, 1828) asserted that

higher education should lay the “foundation” for a general education:

The course of instruction, which is given to the undergraduates in the college, is

not designed to include professional studies. Our object is not to teach that which

is peculiar to any one of the professions; but to lay the foundation which is

common to them all. There are separate schools for medicine, law, and theology,

connected with the college, as well as in various parts of the country; which are

open for the reception of all who are prepared to enter upon the appropriate

studies of their several professions. With these, the academical [sic] course is not

intended to interfere. (Yale University, 1828, p. 9)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anexploratorycasestudyfacultyinvolvementindevelopingwriting-infusedcourseswithintheprofessionaldisci-230805195440-0c70ba2a/75/AN-EXPLORATORY-CASE-STUDY-FACULTY-INVOLVEMENT-IN-DEVELOPING-WRITING-INFUSED-COURSES-WITHIN-THE-PROFESSIONAL-DISCIPLINES-38-2048.jpg)

![33

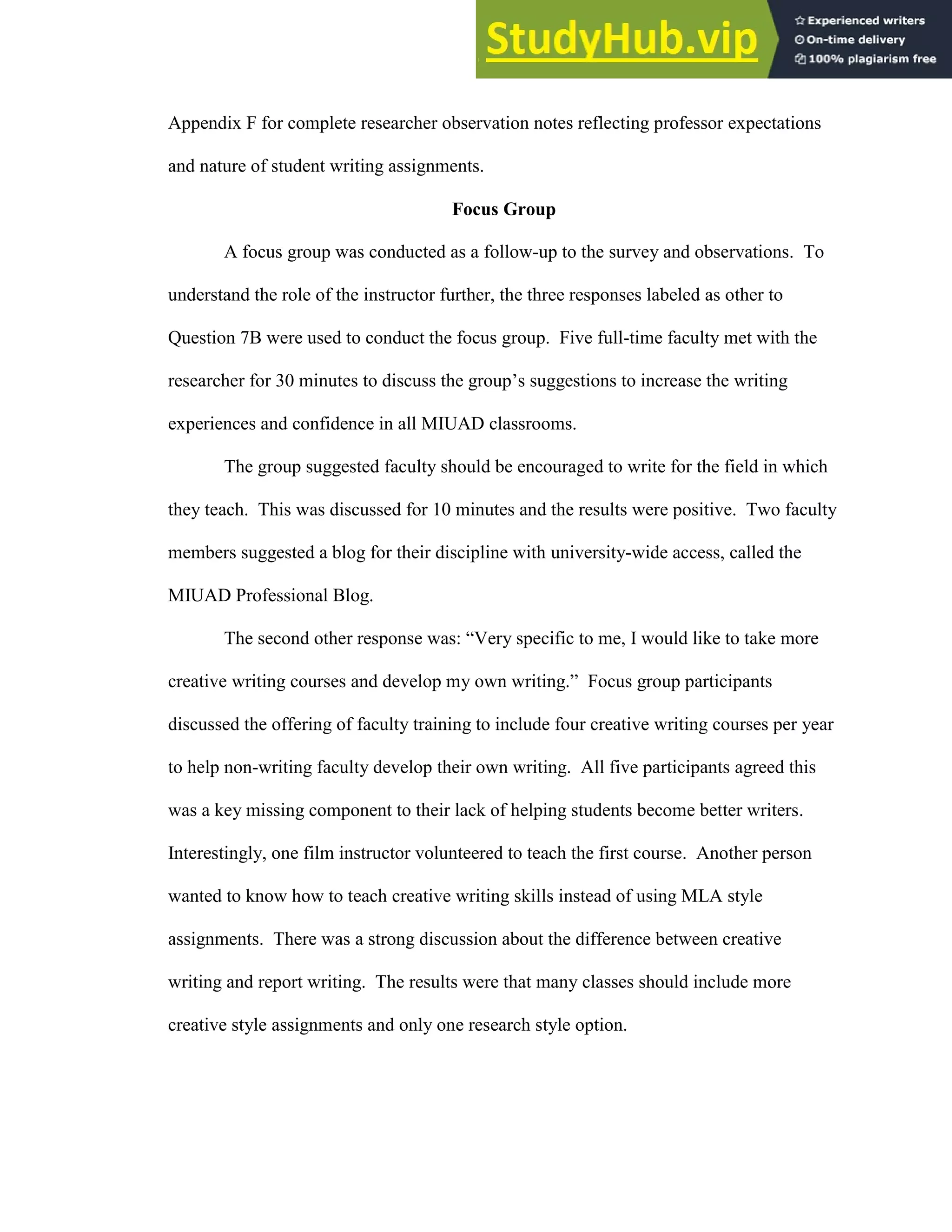

approaches (Bordelon, 2010, p. 258). The report showed support “to integrate classroom

activities . . . with student experience . . . with each other . . . and with the total pattern of

the world in which we live” (Bordelon, 2010, p. 258). In other words, in this theory,

students learn best when they can relate their writing assignments with their lives and

discipline-specific subject matter.

However, despite Weeks’ efforts to support the integration of teaching writing in

the disciplines, the academic community continued to focus on the new freshman

composition course and how it would be the vehicle through which students learned

proper writing skills and etiquette (Bordelon, 2010). Weeks’ approach to teaching and

learning integrative writing included “vocational education, to social studies, to

reforming the teaching of English, to challenging traditional gender constraints . . . of the

time” (Bordelon, 2010, p. 258). The practice during Weeks’ time was to teach writing

and composition as a separate skill rather than as part of content matter.

Composition courses addressed students’ writing skills based on their ability to

read and respond to literary works, separate from discipline-specific writing tenets

(Yageleski, 2012, p. 189). At the time, the question of whether writing skill knowledge

transferred from the English classroom to the discipline-specific classroom remained

unaddressed. “Traditional approaches to [writing] pedagogy . . . tended to be largely

prescriptive and academic, highlighting individual achievement rather than group

cooperation” (Bordelon, 2010, p. 258). The transfer of knowledge between the writing

class and the discipline-specific classroom would come to fruition during the WAC

initiatives of the 21st century through vertical legitimacy of the curriculum and horizontal

outreach. WAC pedagogy of the 21st century focuses on the collective acquisition of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anexploratorycasestudyfacultyinvolvementindevelopingwriting-infusedcourseswithintheprofessionaldisci-230805195440-0c70ba2a/75/AN-EXPLORATORY-CASE-STUDY-FACULTY-INVOLVEMENT-IN-DEVELOPING-WRITING-INFUSED-COURSES-WITHIN-THE-PROFESSIONAL-DISCIPLINES-43-2048.jpg)

![37

reading Dewey’s psychology of learning, that language is used to “organize and maintain

social groups, construct meanings and identities, coordinate behavior, mediate power,

produce change, and create knowledge” (San Diego State University, n.d., para. 1).

Human understanding and processing of new knowledge are facilitated through a process

of association––students understand new information and skills if they are able to relate

them to something familiar and pertinent to them. This is possible though learning within

a community and social interactions with others with similar experiences (Dewey, 2008).

Eurich’s ideas on learning in relation to human experience, the central idea that

writing should be taught in relation to a student’s discipline, gained psychologists’

attention. Dewey embraced the idea of “learning communities” to support collaborative

and contextual learning. Dewey equated subject matter knowledge to human beings’

social experience:

Any problem of scientific inquiry that does not grow out of actual (or “practical”)

social conditions is factitious . . . That which is observed, no matter how carefully

and no matter how accurate the record, is capable of being understood only in

terms of projected consequences of activities . . . Problems with which inquiry

into social subject-matter is concerned must, if they satisfy the conditions of

scientific method, (1) grow out of actual social tensions, needs, “troubles”; (2)

have their subject-matter determined by the conditions that are material means of

bringing about a unified situation, and (3) be related to some hypothesis, which is

a plan and policy for existential resolution of the conflicting social situation.

(Dewey, 2008, p. 499)

Dewey’s philosophical approach to education suggests human beings process knowledge

in a scientific manner and learn and process new information based on their observations

and direct interactions with new information as related to their personal experiences.

Dewey’s embrace of contextual learning would influence the progressive

education movement during the 1950s and 1960s. This point of view supports the idea

that the “content teacher must see that these general [writing] principles are used](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anexploratorycasestudyfacultyinvolvementindevelopingwriting-infusedcourseswithintheprofessionaldisci-230805195440-0c70ba2a/75/AN-EXPLORATORY-CASE-STUDY-FACULTY-INVOLVEMENT-IN-DEVELOPING-WRITING-INFUSED-COURSES-WITHIN-THE-PROFESSIONAL-DISCIPLINES-47-2048.jpg)

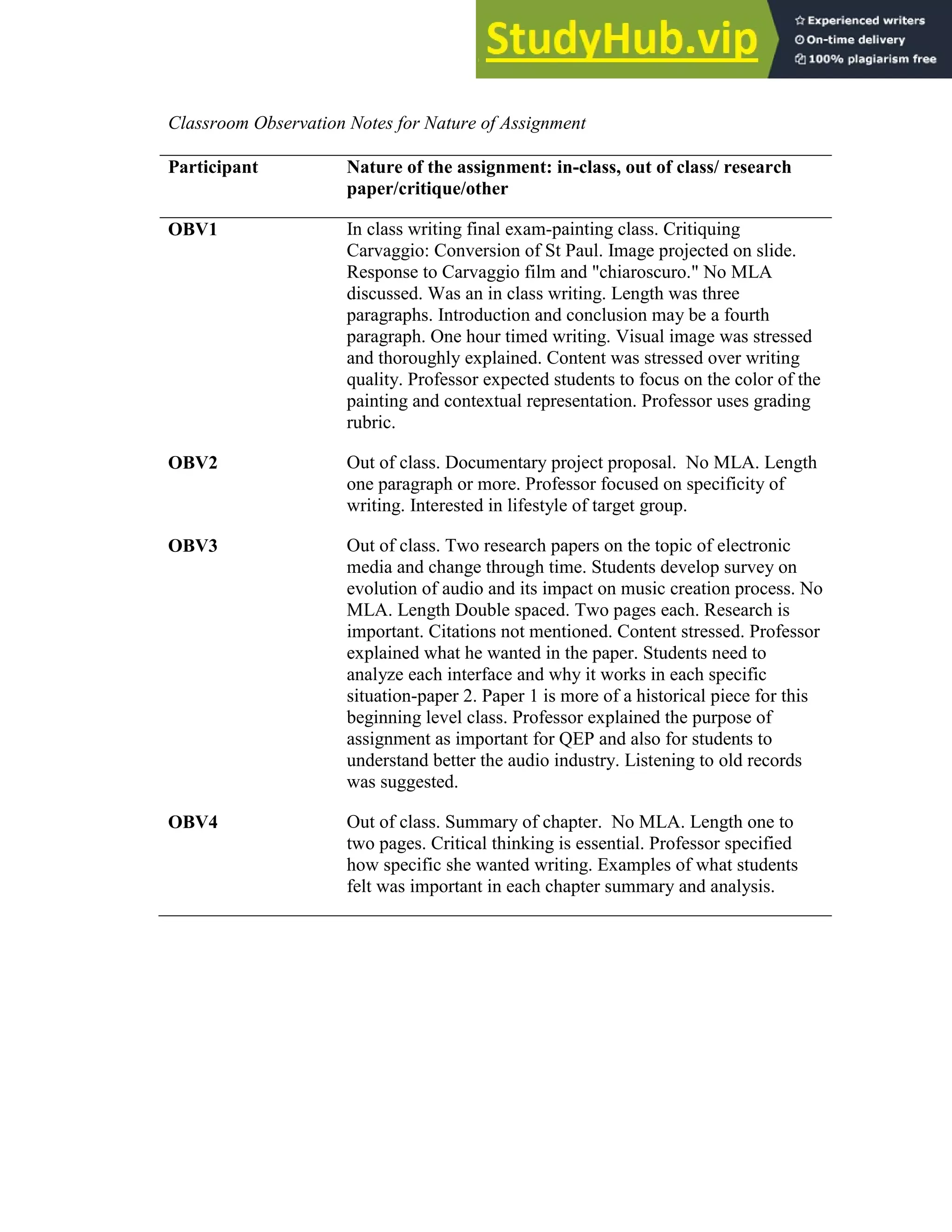

![63

participants as well as work directly with participants during the course of the study.

“This type of case study is used to explore [a] situation in which the intervention being

evaluated has no clear, single set of outcomes” (Yin, as cited in Baxter & Jack, 2008, p.

548). A quantitative method would not work in this study for two reasons: the number of

participants and the purpose of the study. Because a hypothesis was not possible given

the purpose of the study, which was to discover new information rather than test a

variable or compare results to existing data, no statistical analysis was warranted

(Creswell, 2007; Johnson & Christensen, 2007).

The exploratory case study method enables researchers to determine participants’

realities and experiences during the study and state claims based on the findings. This

method allows researchers to examine a person or situation contextually and within a

natural setting (Creswell, 2007). Through case study methodology, researchers are able

to conduct a contextual analysis of participant experiences and develop new insights or

expand on the existing body of knowledge on the topic of this study (Johnson &

Christensen, 2007). This approach was appropriate for this study because the research

questions asked in what ways and why participants infused writing in their discipline-

specific classrooms (Baxter & Jack, 2008).

The researcher collected data from participants primarily through a qualitative

survey, individual classroom observations, and a focus group. In the qualitative survey

for this study, participants were able to share specific information about their academic

backgrounds, techniques for infusing writing in the classroom, as well as their

suggestions for improving the current QEP pilot for university-wide implementation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anexploratorycasestudyfacultyinvolvementindevelopingwriting-infusedcourseswithintheprofessionaldisci-230805195440-0c70ba2a/75/AN-EXPLORATORY-CASE-STUDY-FACULTY-INVOLVEMENT-IN-DEVELOPING-WRITING-INFUSED-COURSES-WITHIN-THE-PROFESSIONAL-DISCIPLINES-73-2048.jpg)

![64

Additionally, the qualitative survey allowed participants to make

recommendations, share best practices, and suggest ways to implement a writing

initiative in an art and design university setting. In this case study, the primary goal of

classroom observations was to note instructor-student behavior patterns during class

discussions regarding writing tasks and projects. In addition, observing participants in

their natural setting in the classroom gave the researcher insight into how the participants

explained writing assignments to students in class (Yin, 2011). Conversations between

students and comments made during class discussions helped the researcher determine

common patterns and elements in how adults perceive and understand academic writing,

providing clarity and understanding to the information given in the focus group to allow

the researcher to create rich thick descriptions (Yin, 2011).

Finally, given the limited formal research on WAC within an art and design

university, a small group of participants provided personal and specific information

regarding the QEP initiative within MIUAD. The focus group interviews conducted for

this study revealed participants’ perspectives on academic writing within a professional

academic setting, specifically art and design majors.

The gap in the literature showed “boundaries are not clear between the

phenomena [writing-fusion in the professional disciplines] and the context [a regionally

accredited art and design university]” (Baxter & Jack, 2008, p. 545). Moreover, in

situations where there are little formal, quantifiable data on a particular topic, an

exploratory case study allows insight into the topic and the allowable sample size is

small. According to Yin (2011), a sample size of seven to 12 participants is ideal for an

exploratory single case study as used in this research project (p. 30).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anexploratorycasestudyfacultyinvolvementindevelopingwriting-infusedcourseswithintheprofessionaldisci-230805195440-0c70ba2a/75/AN-EXPLORATORY-CASE-STUDY-FACULTY-INVOLVEMENT-IN-DEVELOPING-WRITING-INFUSED-COURSES-WITHIN-THE-PROFESSIONAL-DISCIPLINES-74-2048.jpg)

![124

Shockley-Zalabak, P. S. (2009). Fundamentals of organizational communication:

Knowledge, sensitivity, skills, values (7th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Learning

Solutions.

Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges. (2012). The

principles of accreditation: Foundations for quality enhancement (4th ed.).

Decatur, GA: Author.

Spafford, I. (1943). Building a curriculum for general education: A description of the

general education program. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Taylor, B., & Kroth, M. (2009). Andragogy’s transition into the future: Meta-analysis of

andragogy and its search for a measurable instrument. Journal of Adult

Education, 38(1), 1-10.

Thaiss, C., & Porter, T. (2010). The state of WAC/WID in 2010: Methods and results of

the U.S. survey of the International WAC/WID Mapping Project. National

Council of Teachers of English (NCTE), 16(3), 534-570.

Vander Ark, T. (2013, February 19). Writing across the curriculum with the Literacy

Design Collaborative. Education Week. Retrieved from

http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/on_innovation/2013/02

/writing_across_the_curriculum_with_the_literacy_design_collaborative.html

Vasilachis de Gialdino, I. (2011). Ontological and epistemological foundations of

qualitative research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative

Social Research, 10(2). Retrieved from http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-

fqs0902307

Weimer, W. (2013, March 6). What types of writing assignments are in your syllabus?

[Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-

professor-blog/what-types-of-writing-assignments-are-in-your-syllabus/

Wingate, U., Andon, N., & Cogo, A. (2011). Embedding academic writing instruction

into subject teaching: A case study. Active Learning in Higher Education, 12(1),

69-81.

Woodward-Kron, R. (2008). More than just jargon—Nature and role of specialist

language in learning disciplinary knowledge. Journal of English for Academic

Purposes, 7, 234-249.

Woodward-Kron, R. (2009). “This means that…”: A linguistic perspective of writing and

learning in a discipline. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 8, 165-179.

Yageleski, R. P. (2012, February). Writing as praxis. English Education, 44(2), 188-204.

Yale University. (1828). Reports of the course of instruction in Yale College. New

Haven, CT: Hezekiah Howe.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anexploratorycasestudyfacultyinvolvementindevelopingwriting-infusedcourseswithintheprofessionaldisci-230805195440-0c70ba2a/75/AN-EXPLORATORY-CASE-STUDY-FACULTY-INVOLVEMENT-IN-DEVELOPING-WRITING-INFUSED-COURSES-WITHIN-THE-PROFESSIONAL-DISCIPLINES-134-2048.jpg)