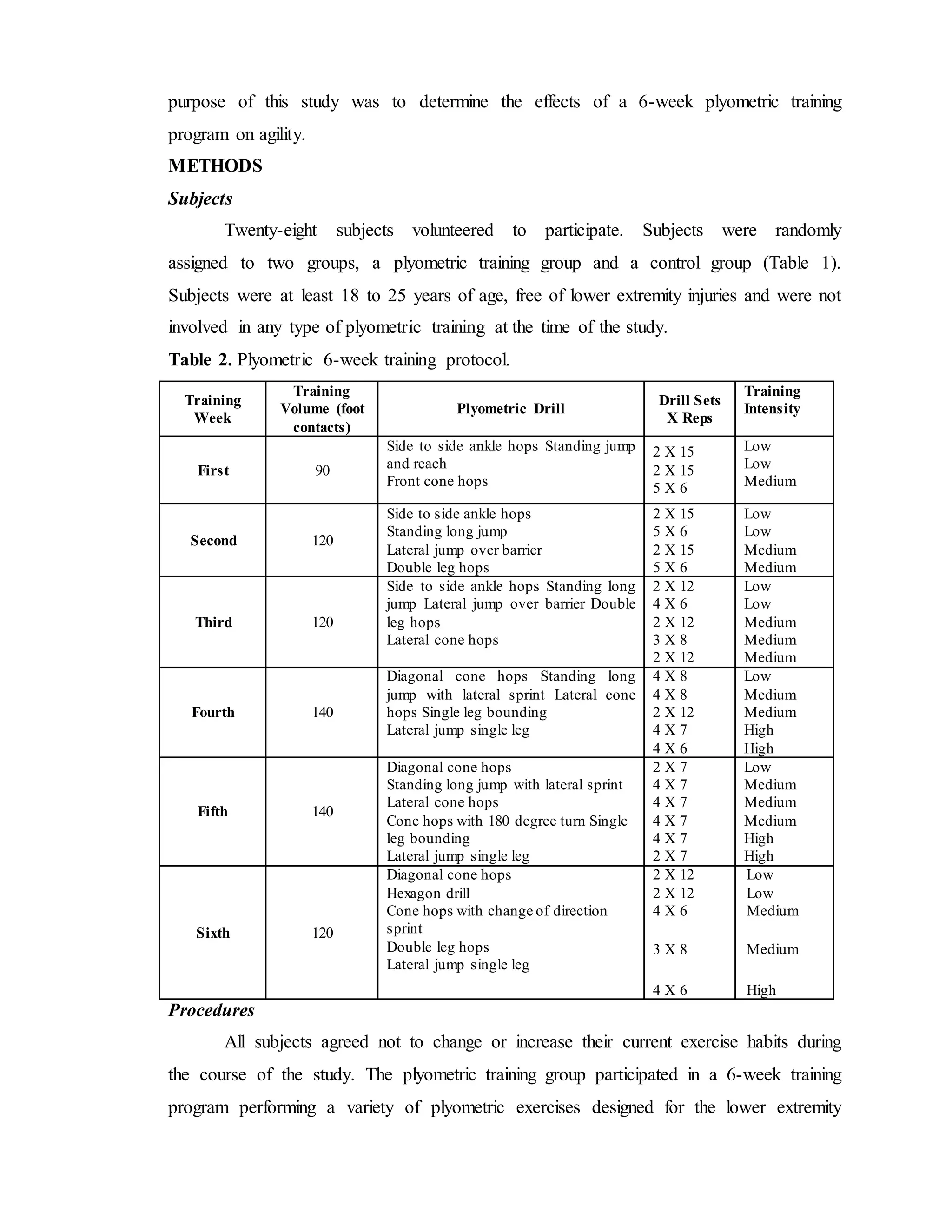

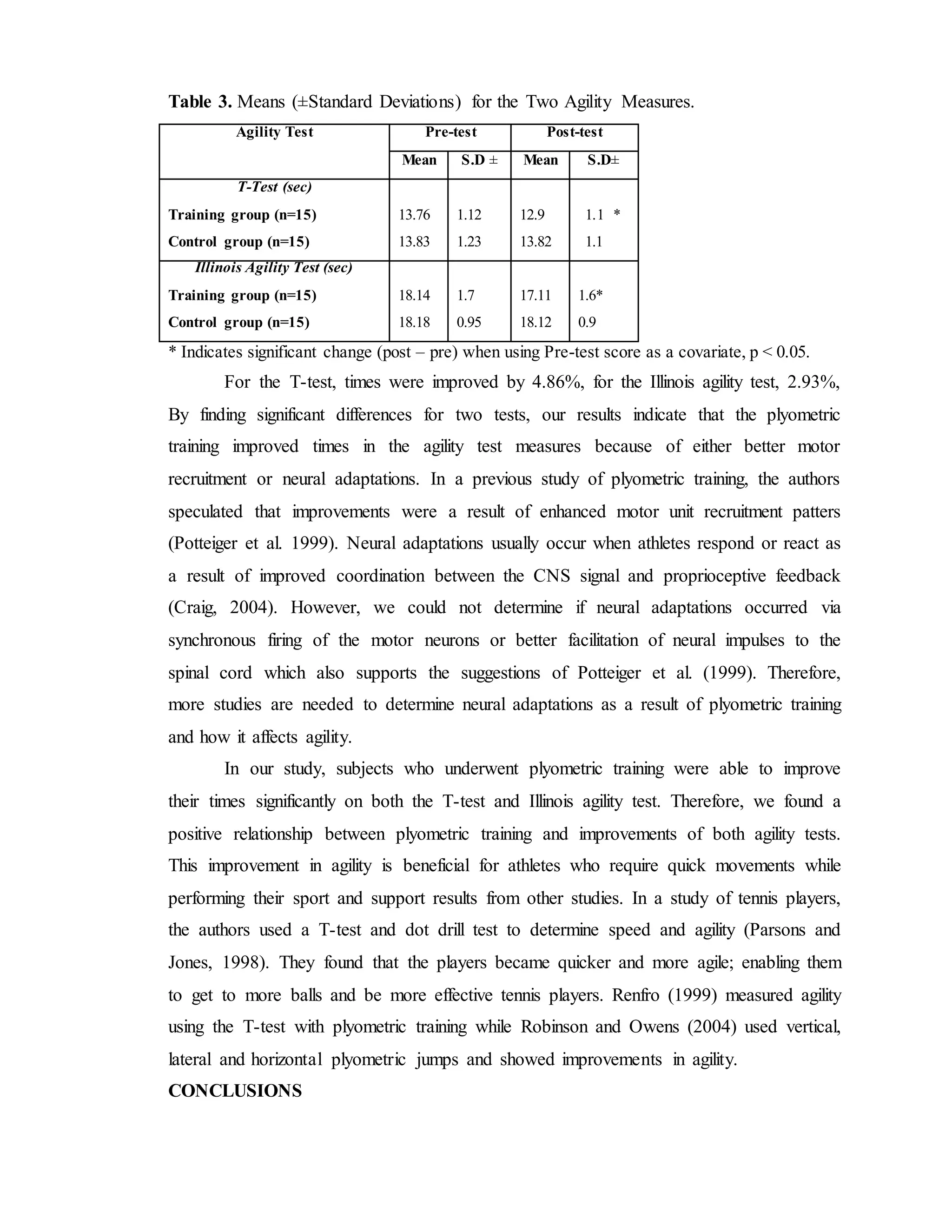

This study examined the effects of a 6-week plyometric training program on agility among athletes. 28 subjects were randomly assigned to a plyometric training group or a control group. The training group performed plyometric exercises 2 times per week for 6 weeks, while the control group did not train. Both groups were tested on the T-test and Illinois Agility Test before and after the training. The results showed that the training group significantly improved their times on both agility tests after training, while the control group did not improve. This suggests that 6 weeks of plyometric training can effectively improve an athlete's agility.