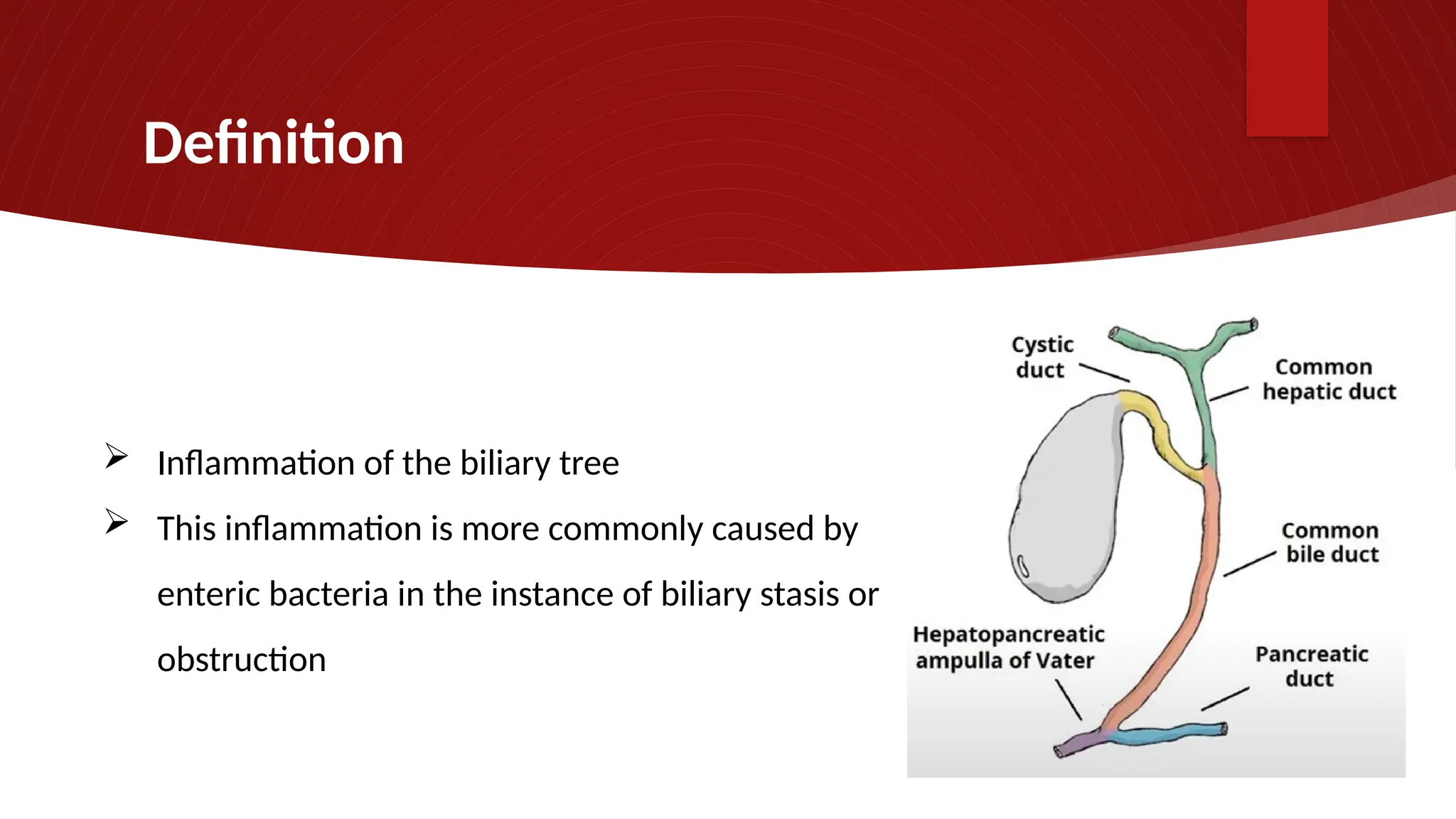

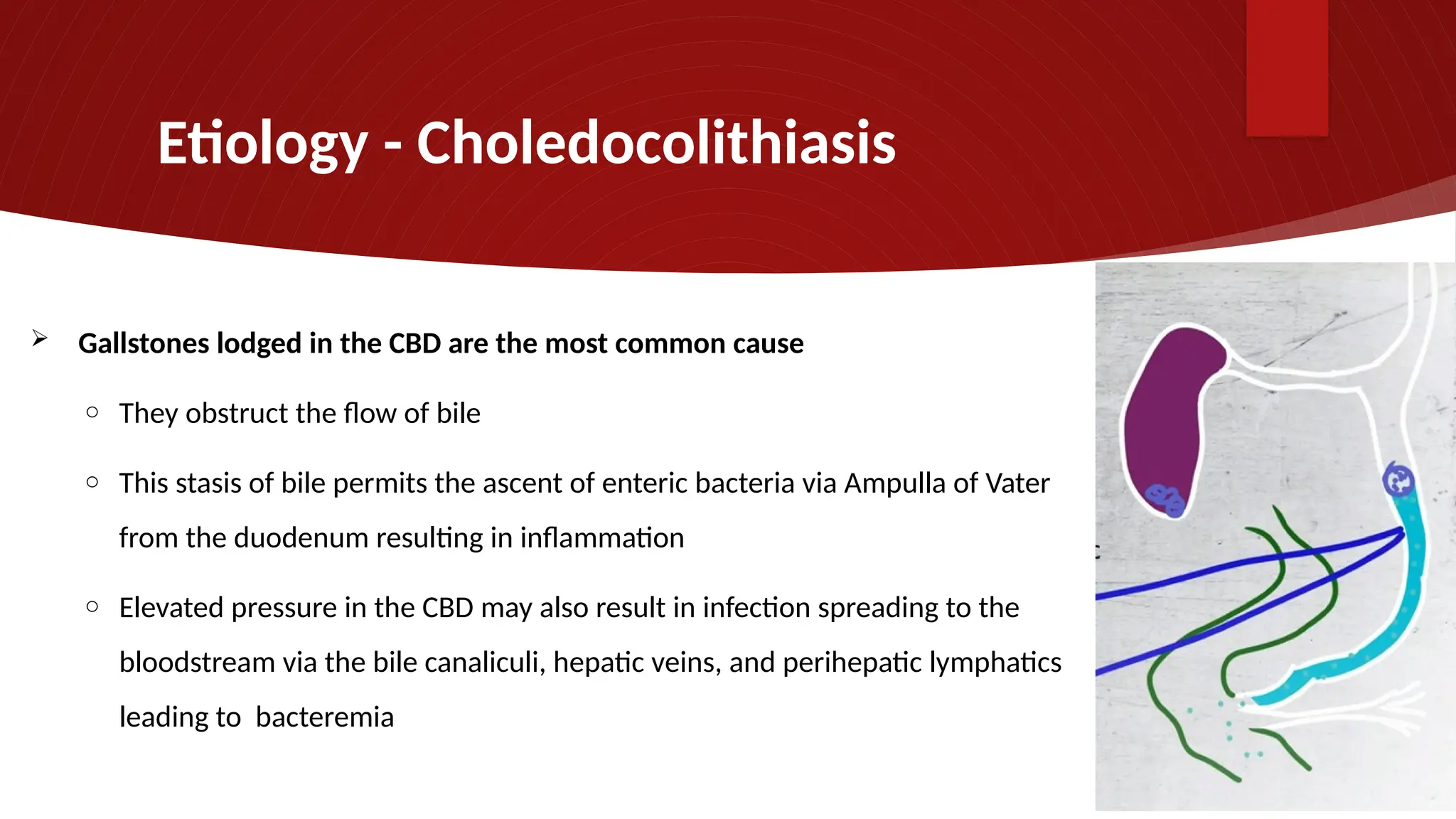

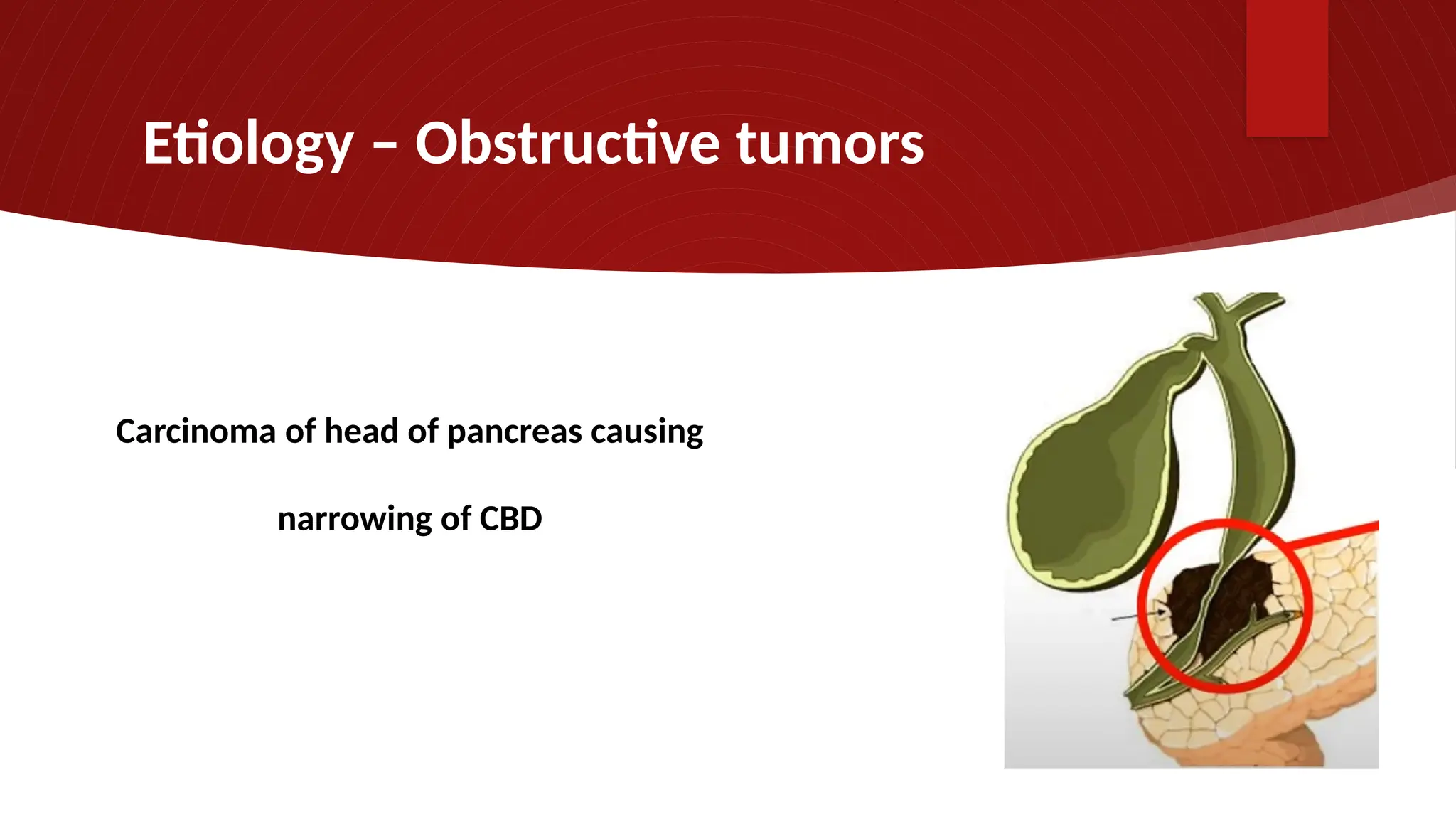

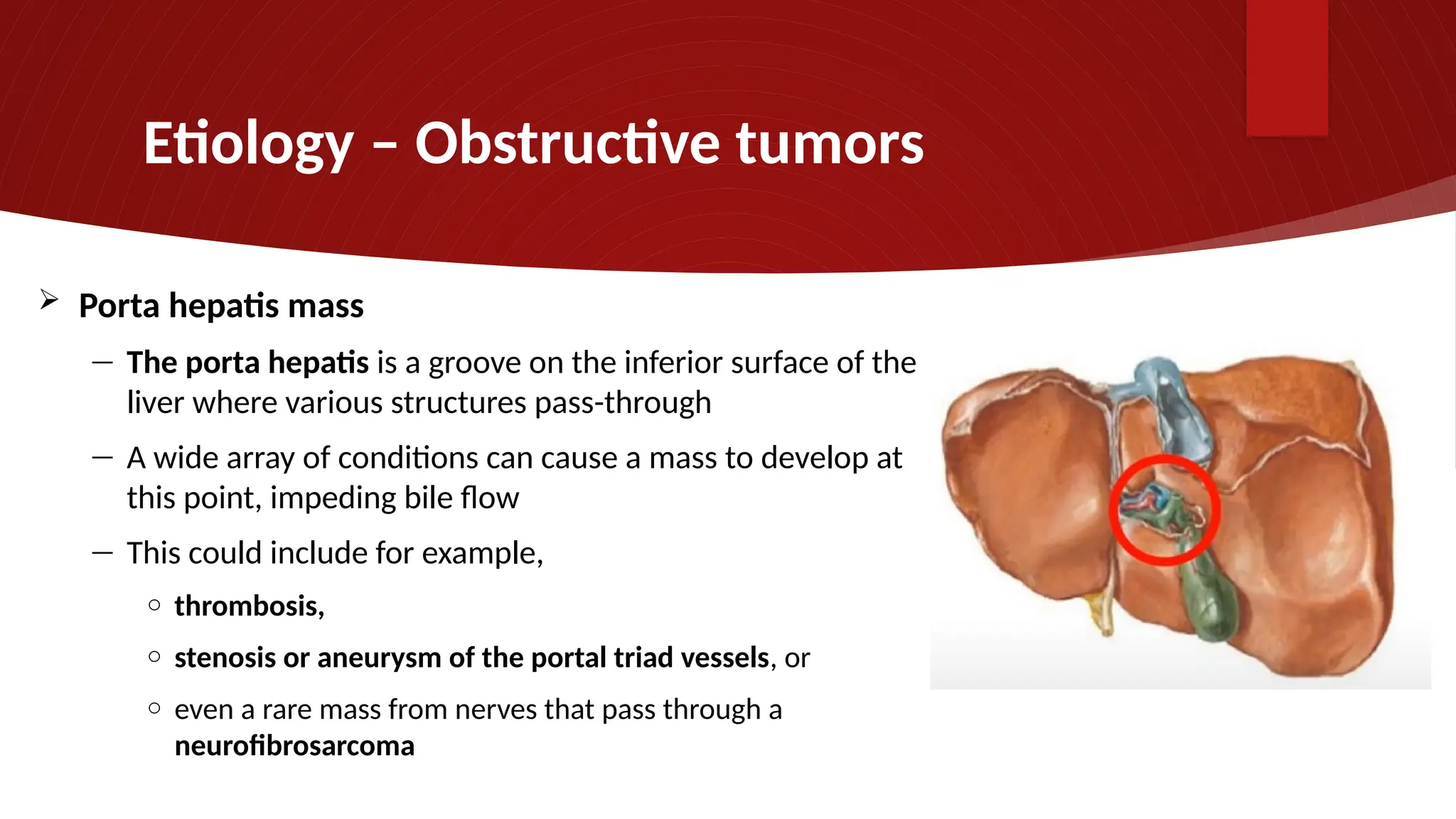

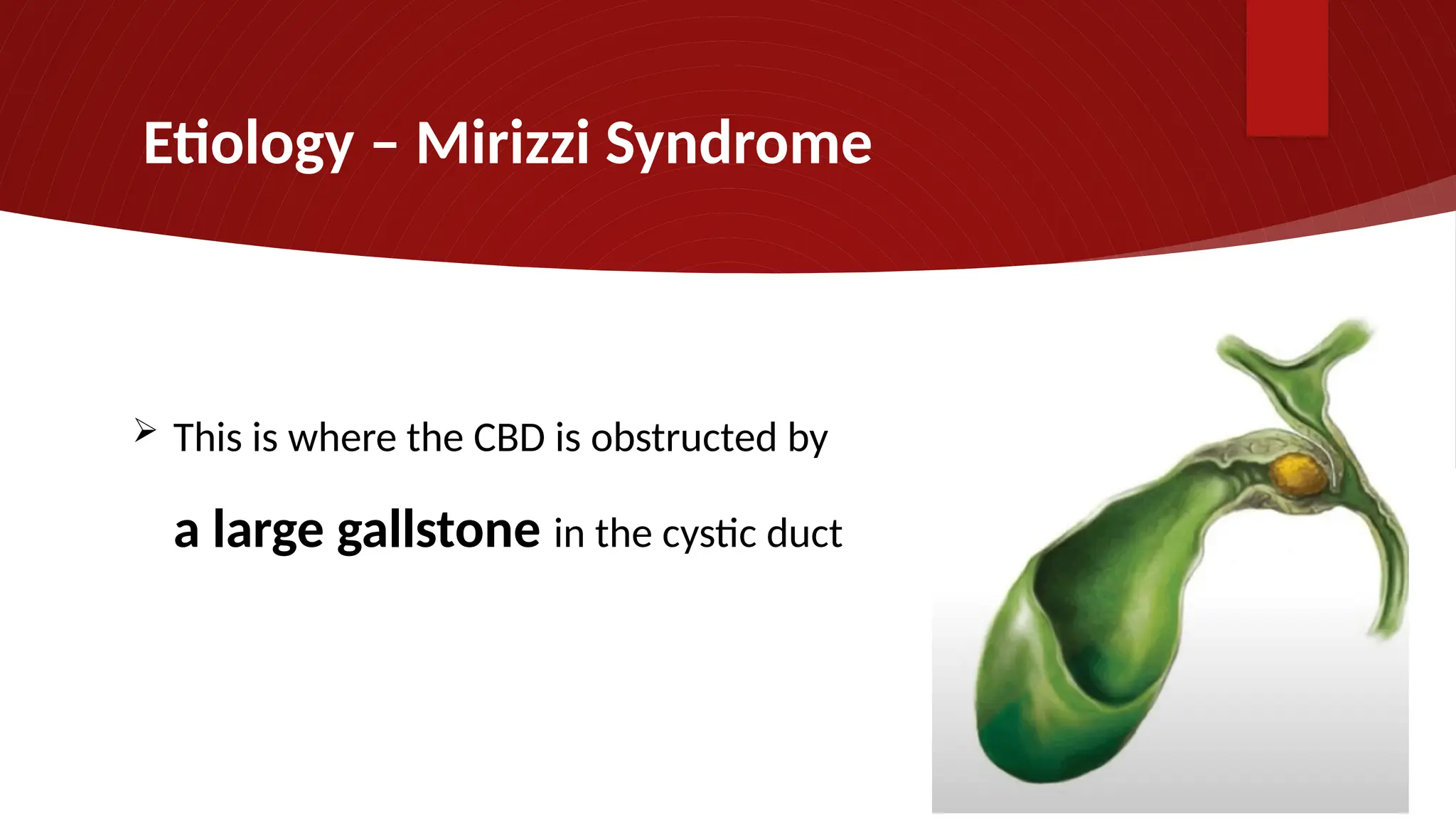

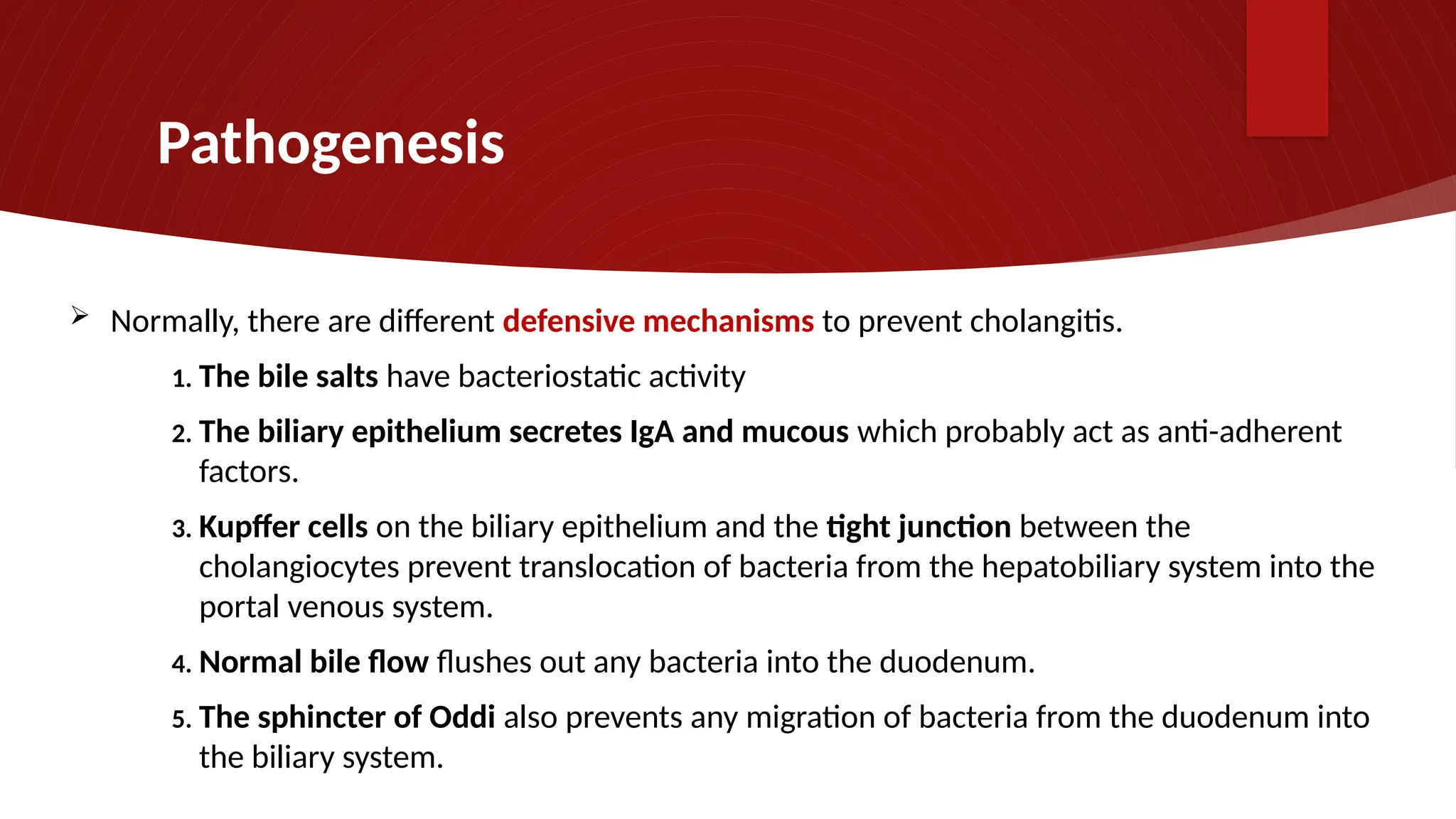

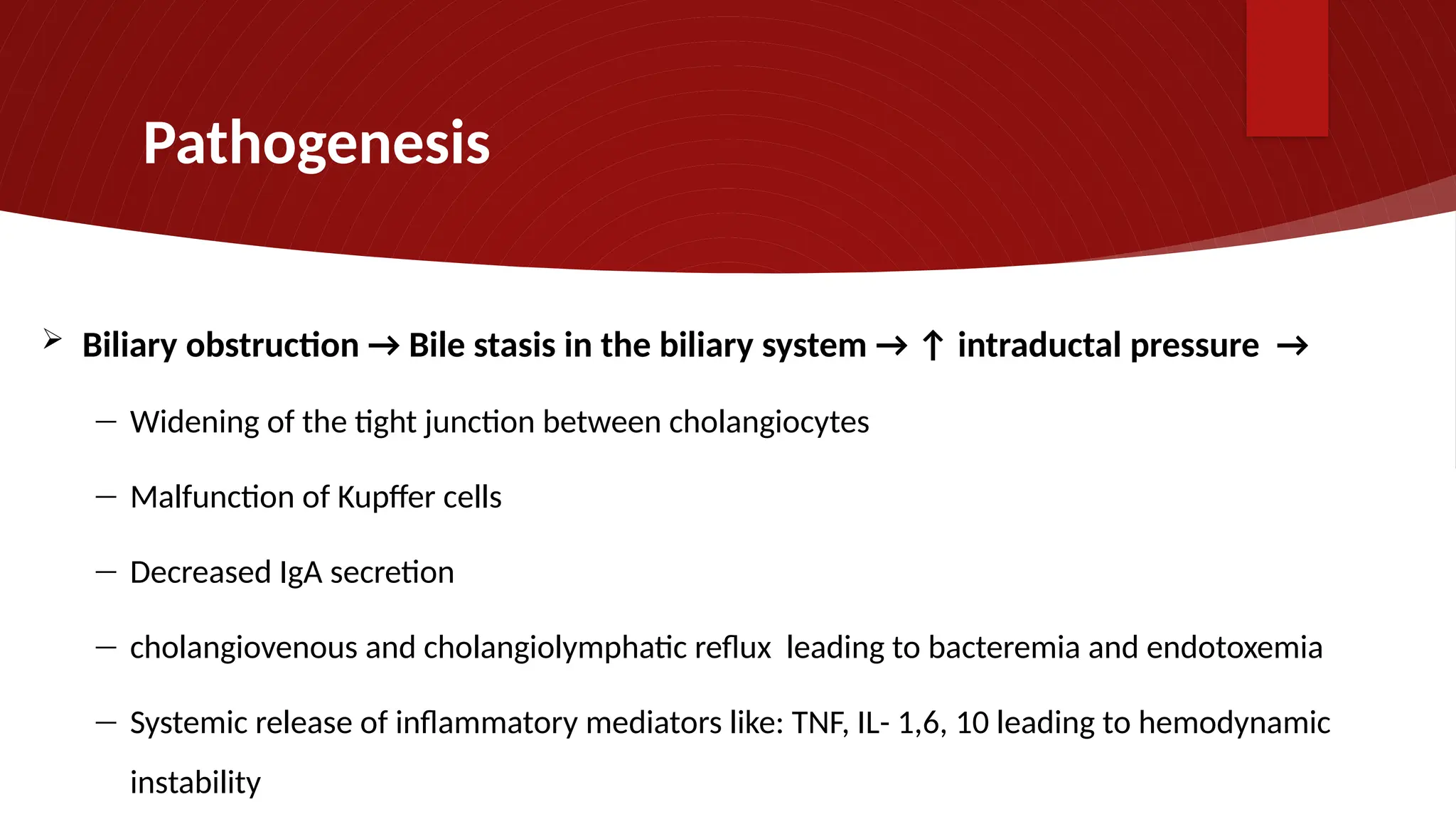

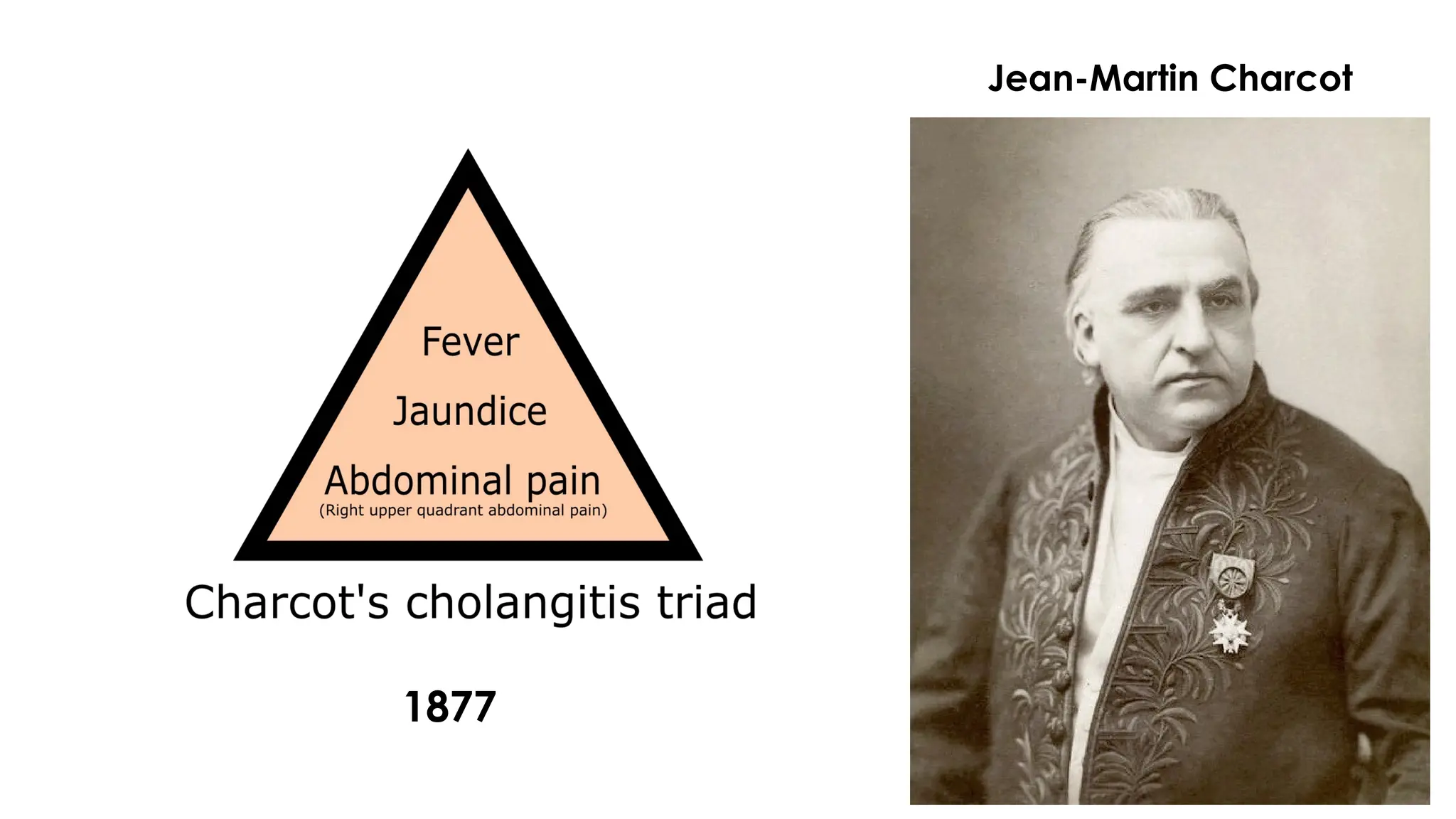

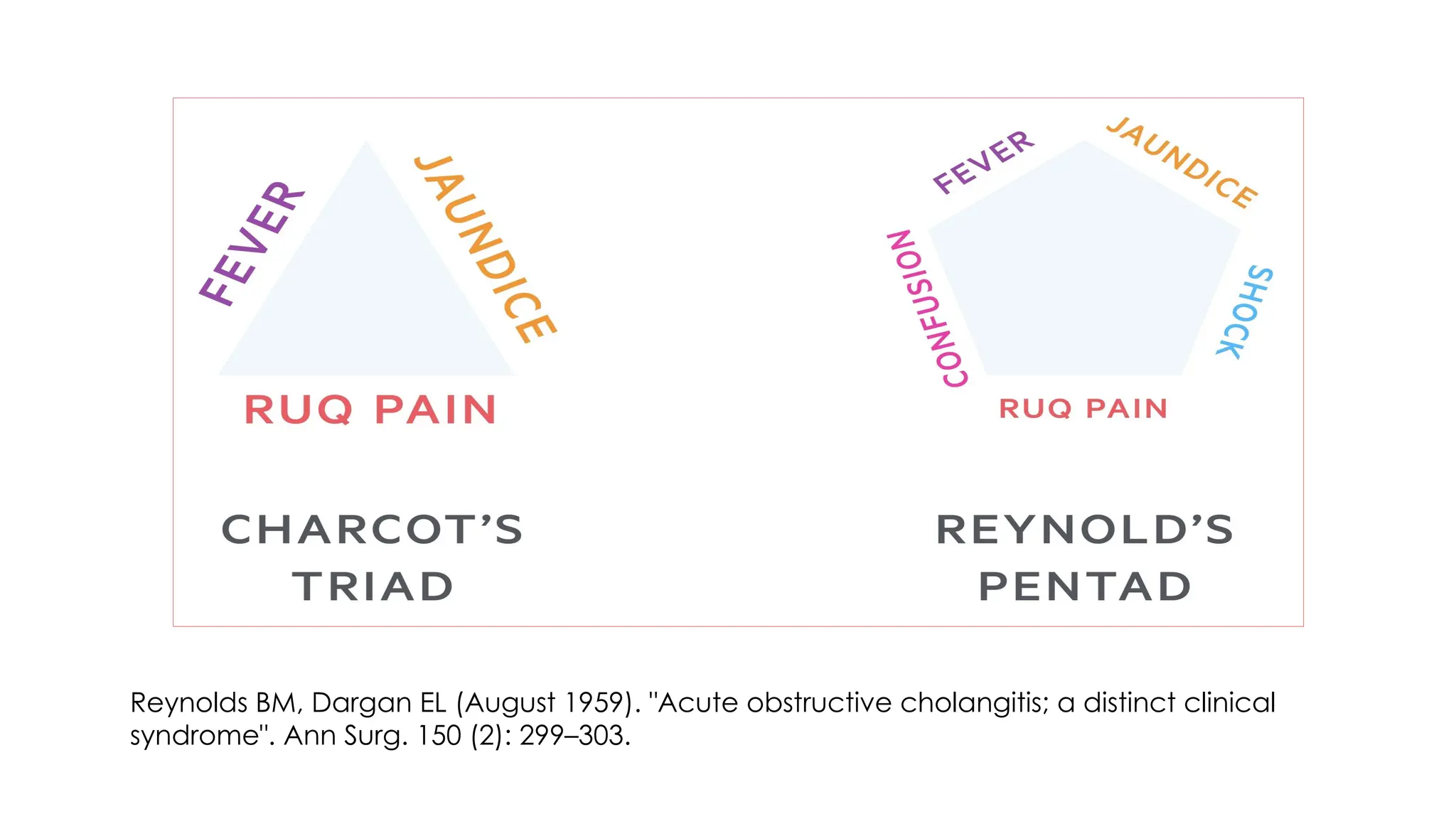

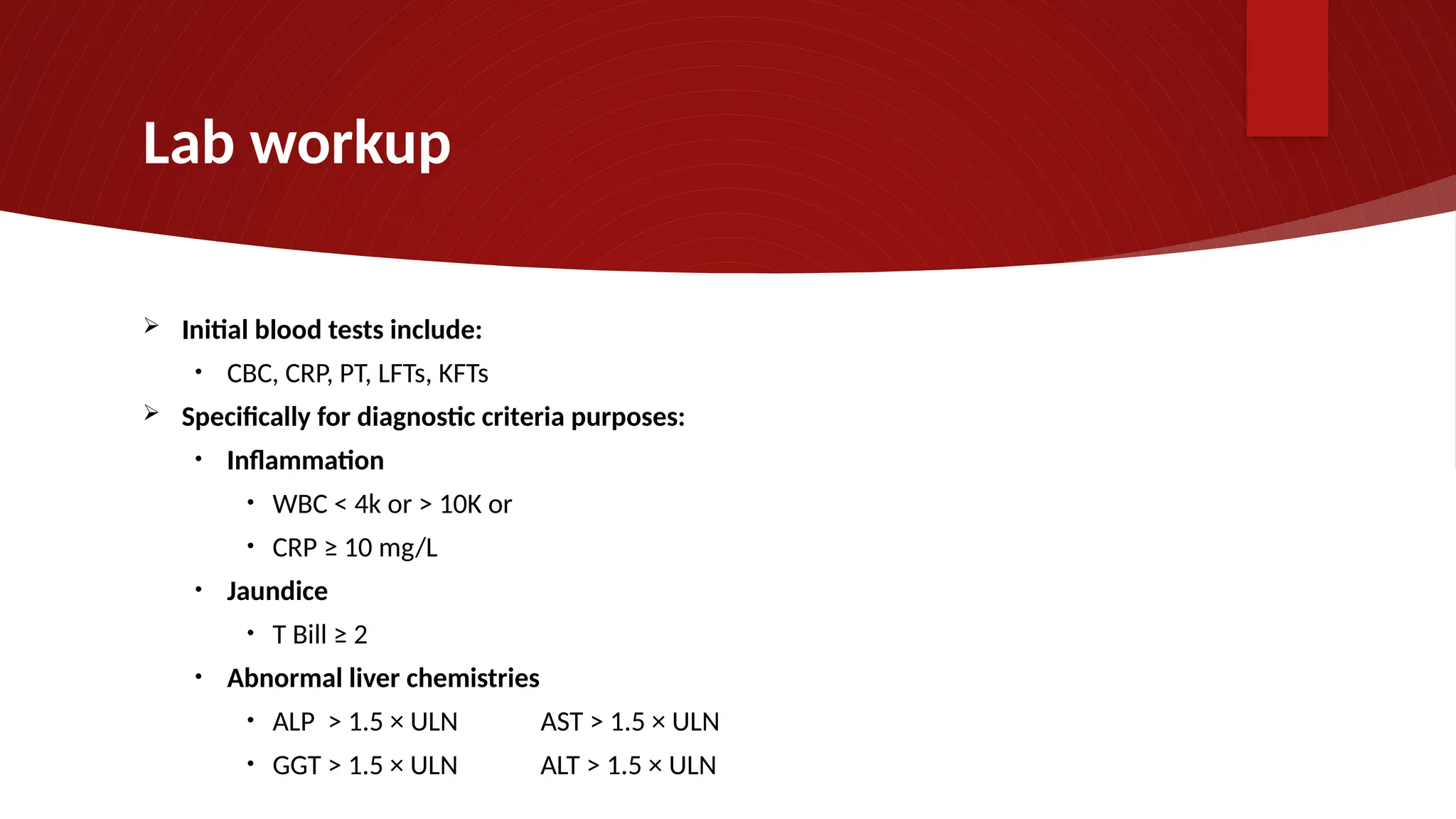

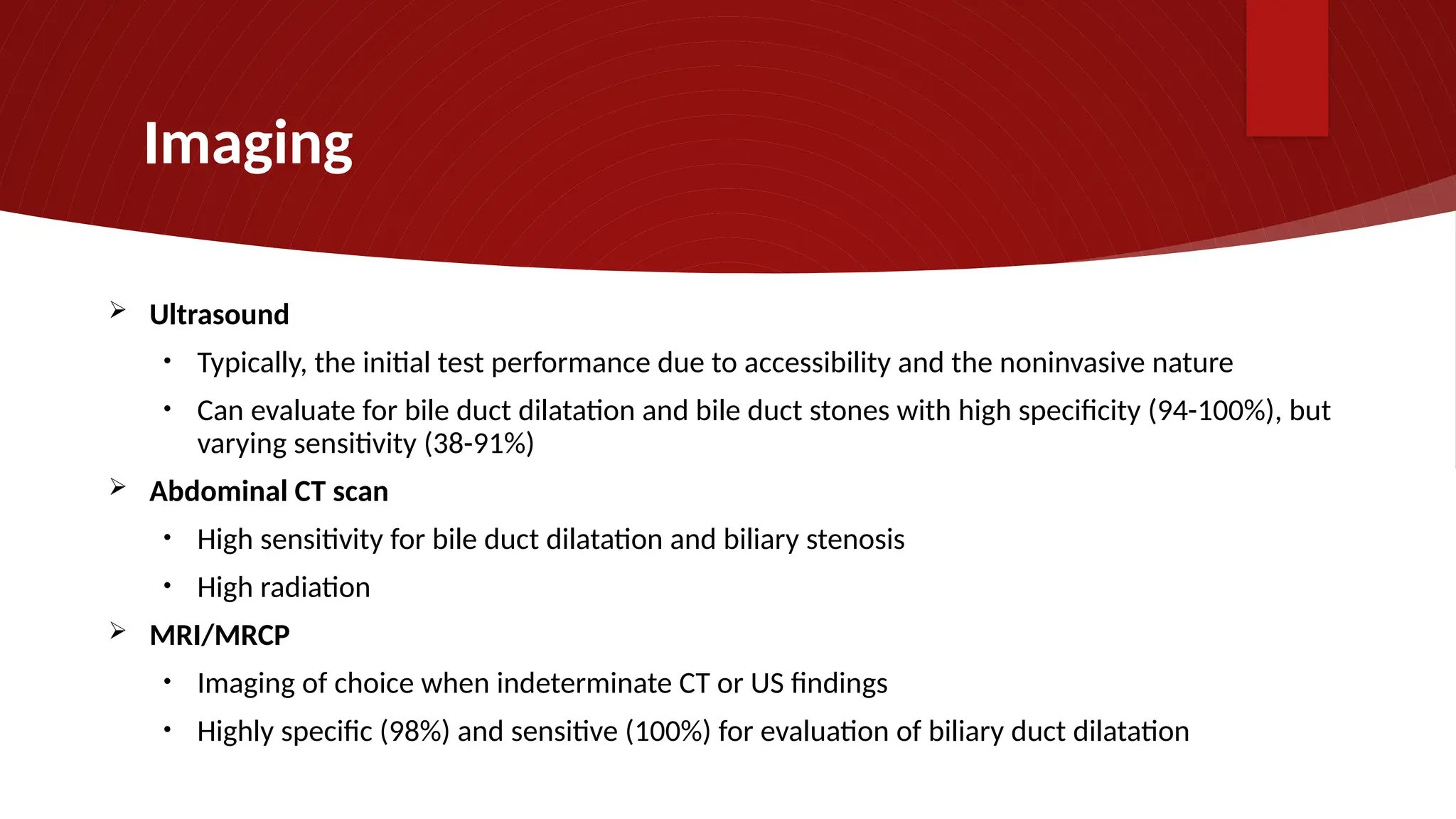

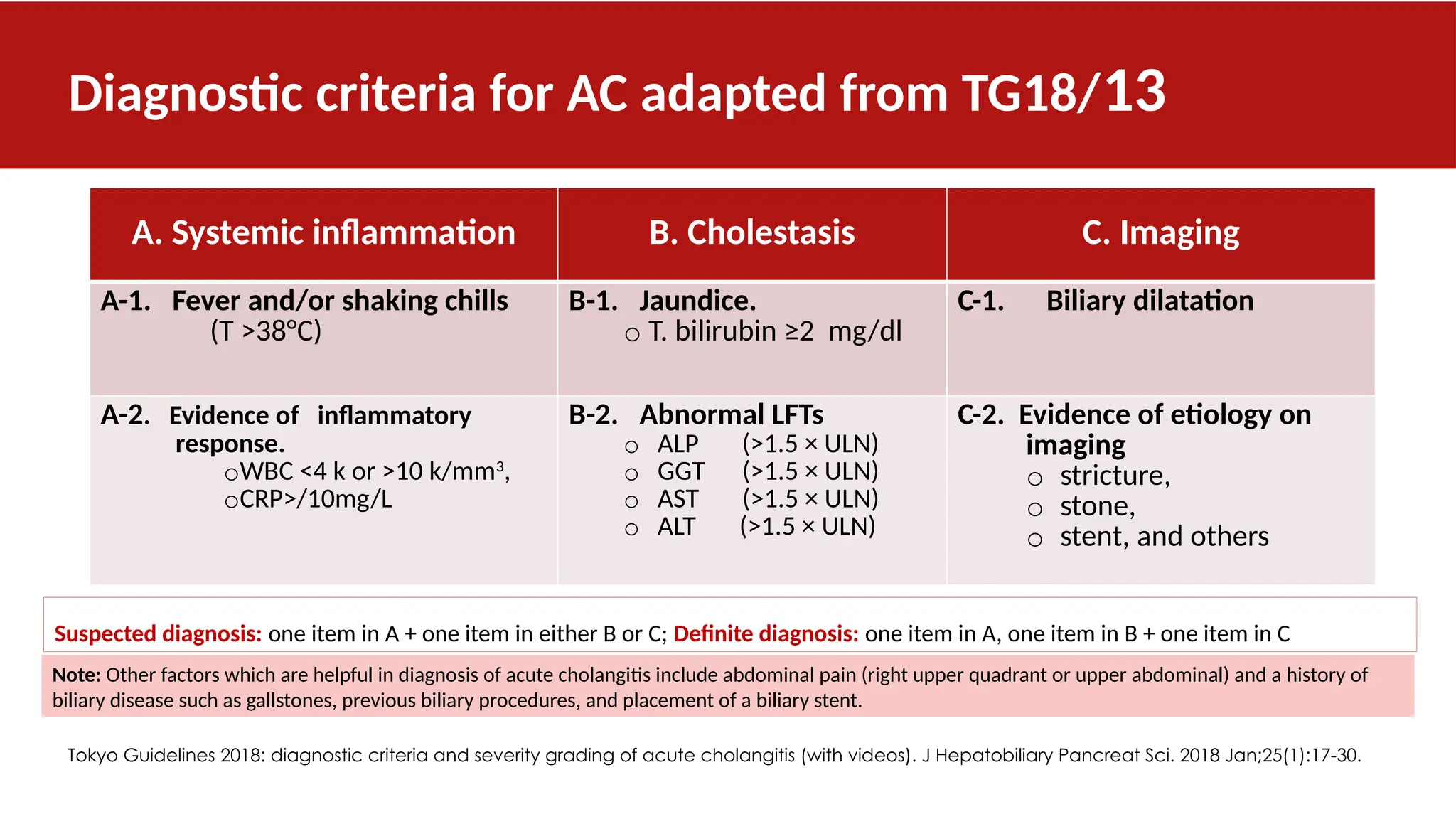

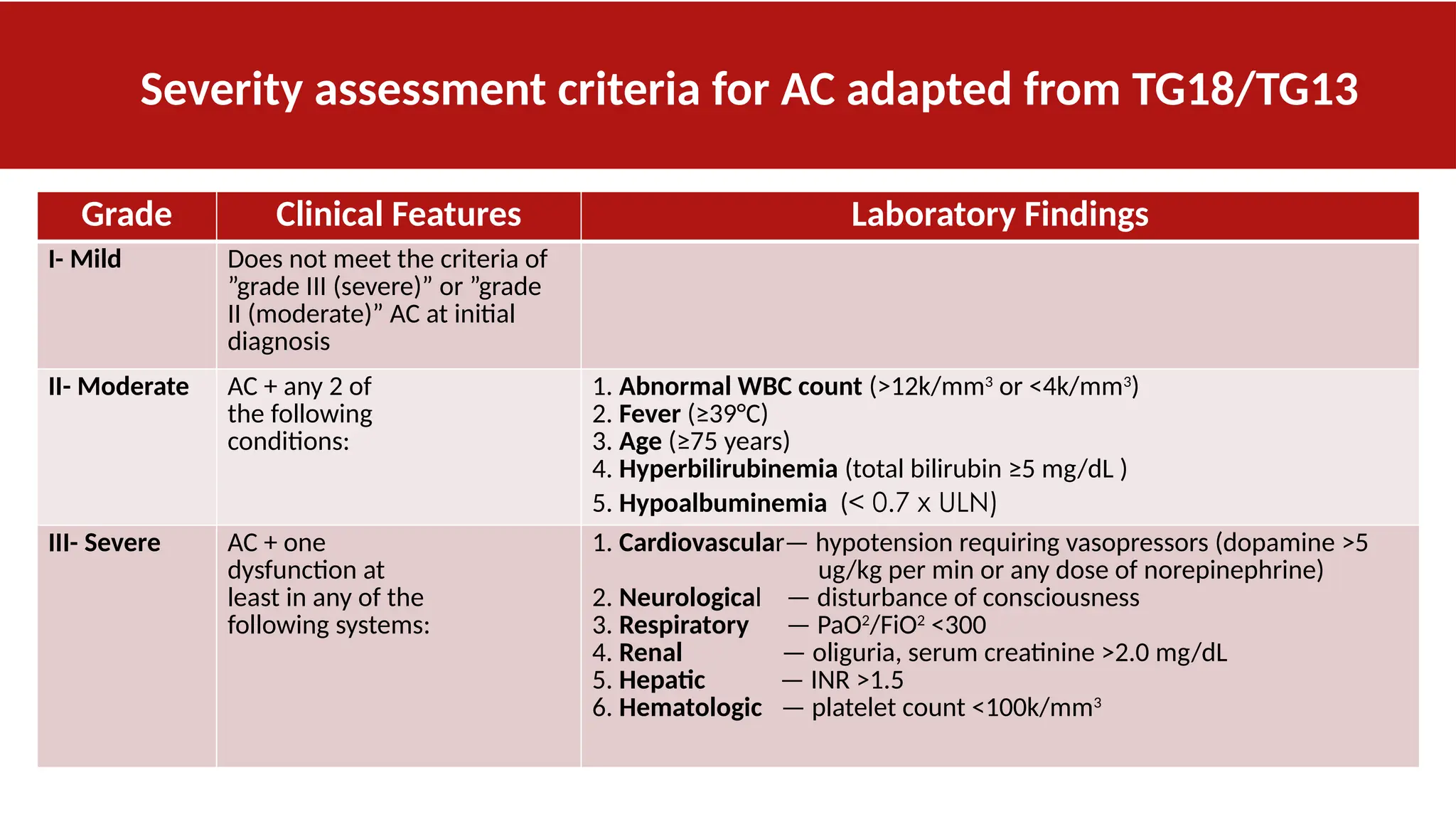

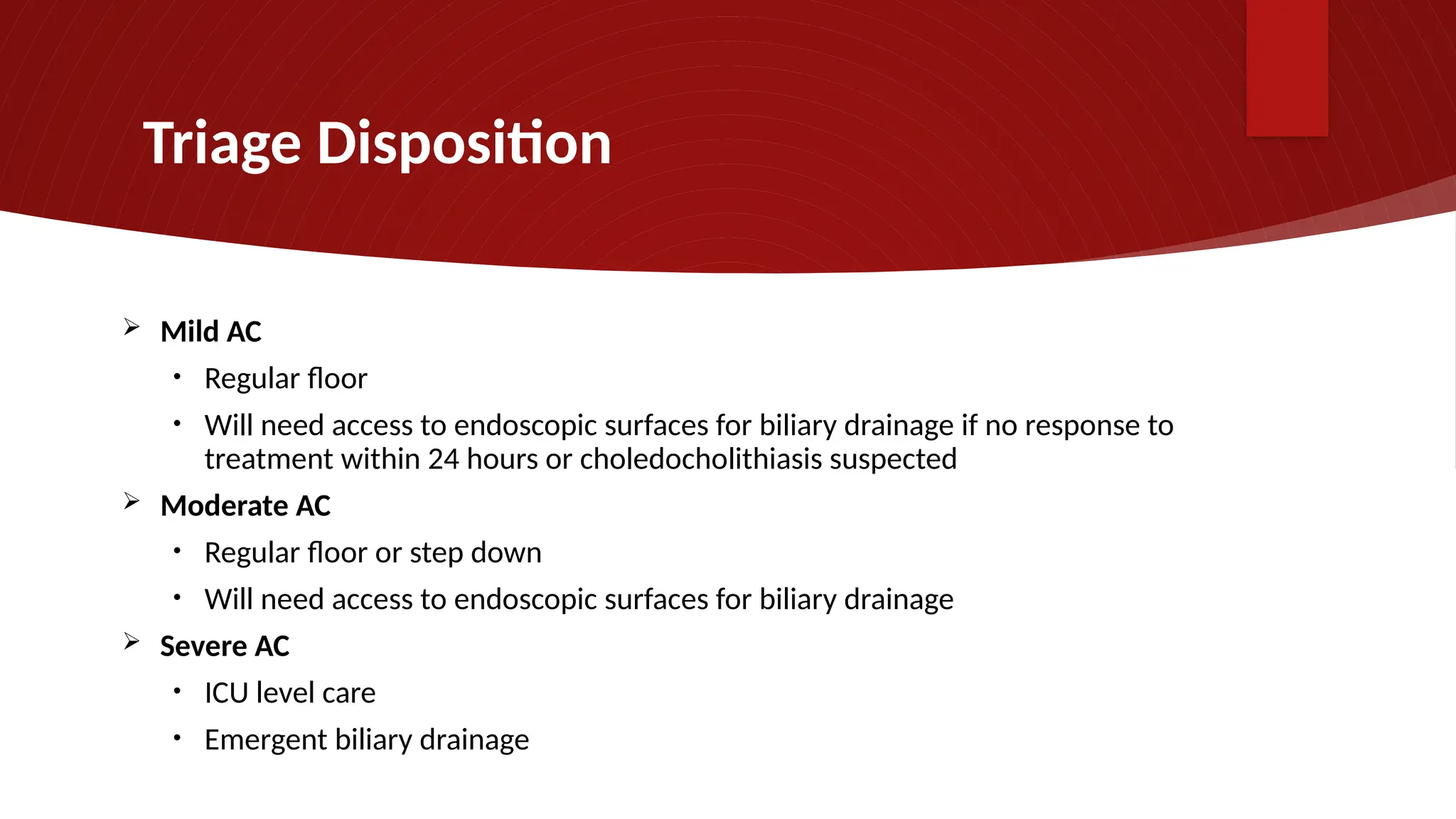

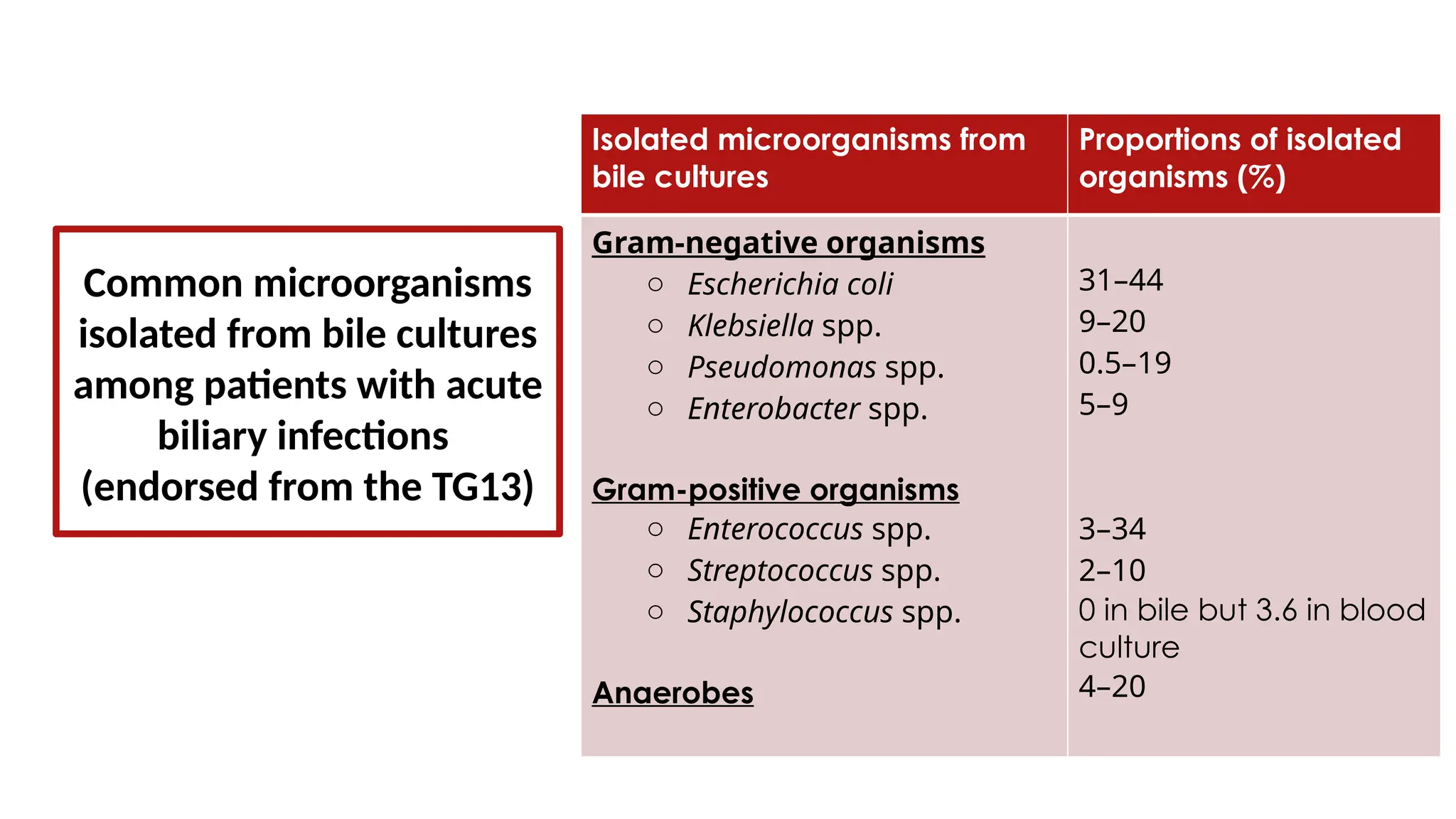

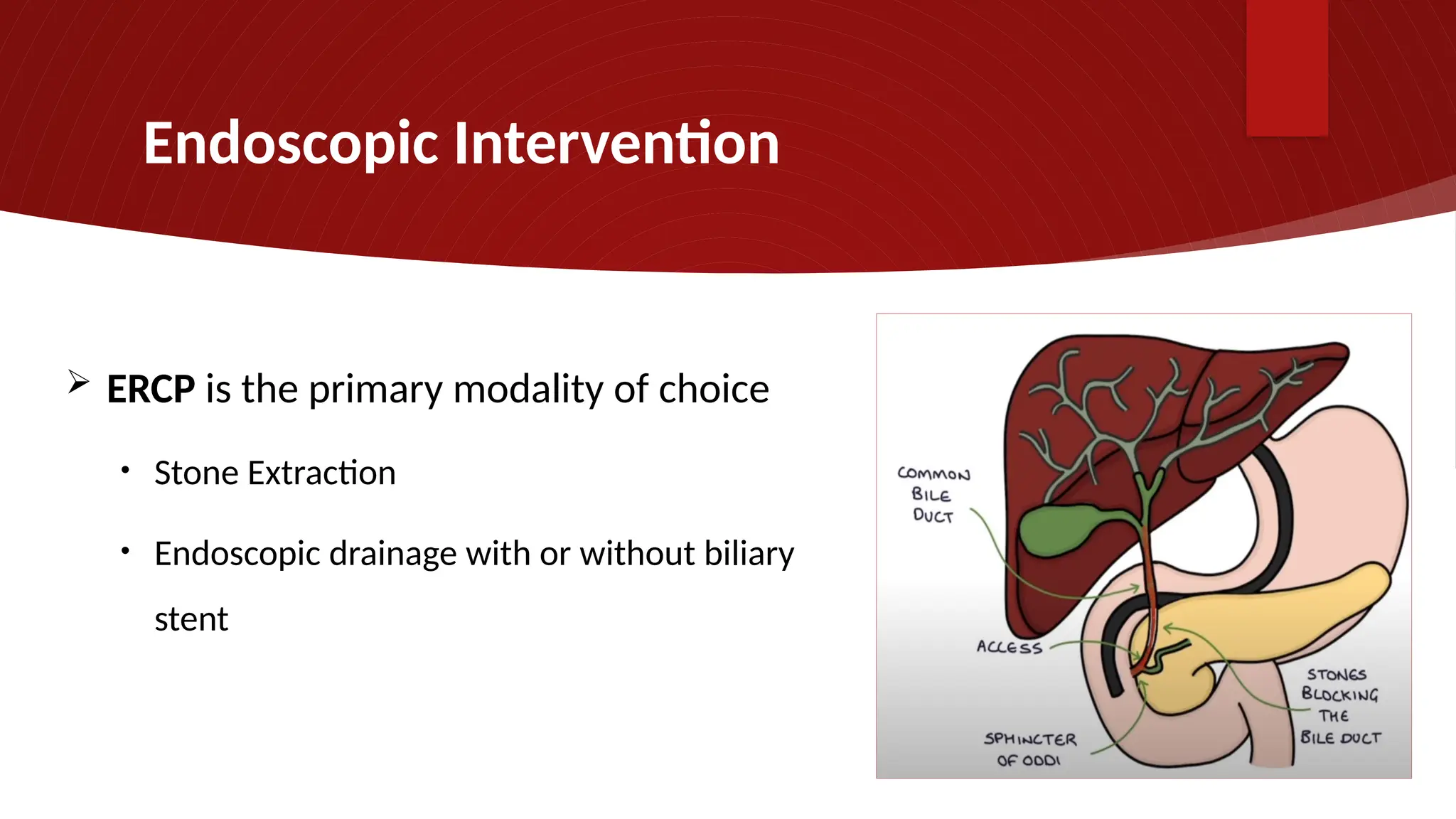

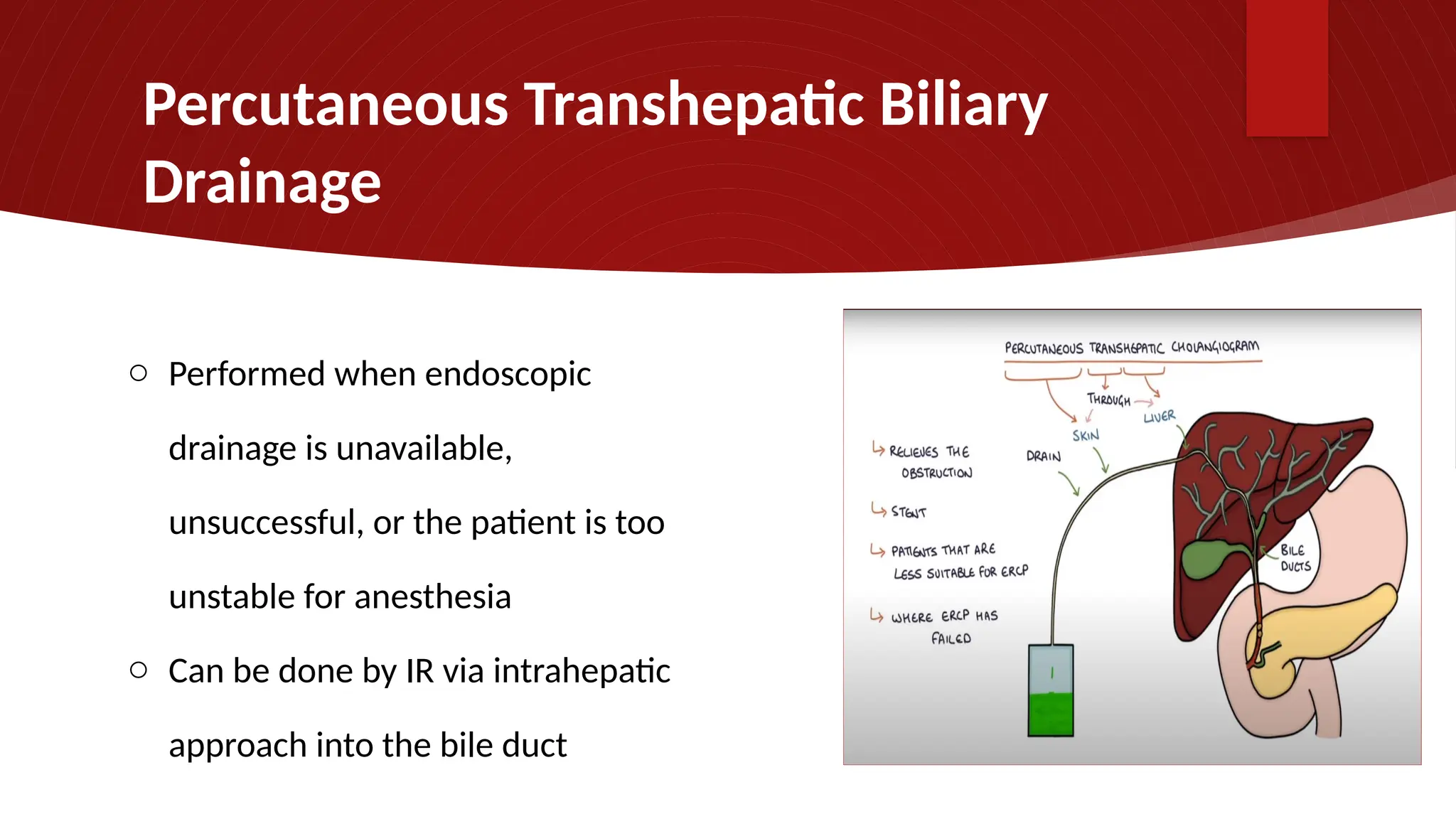

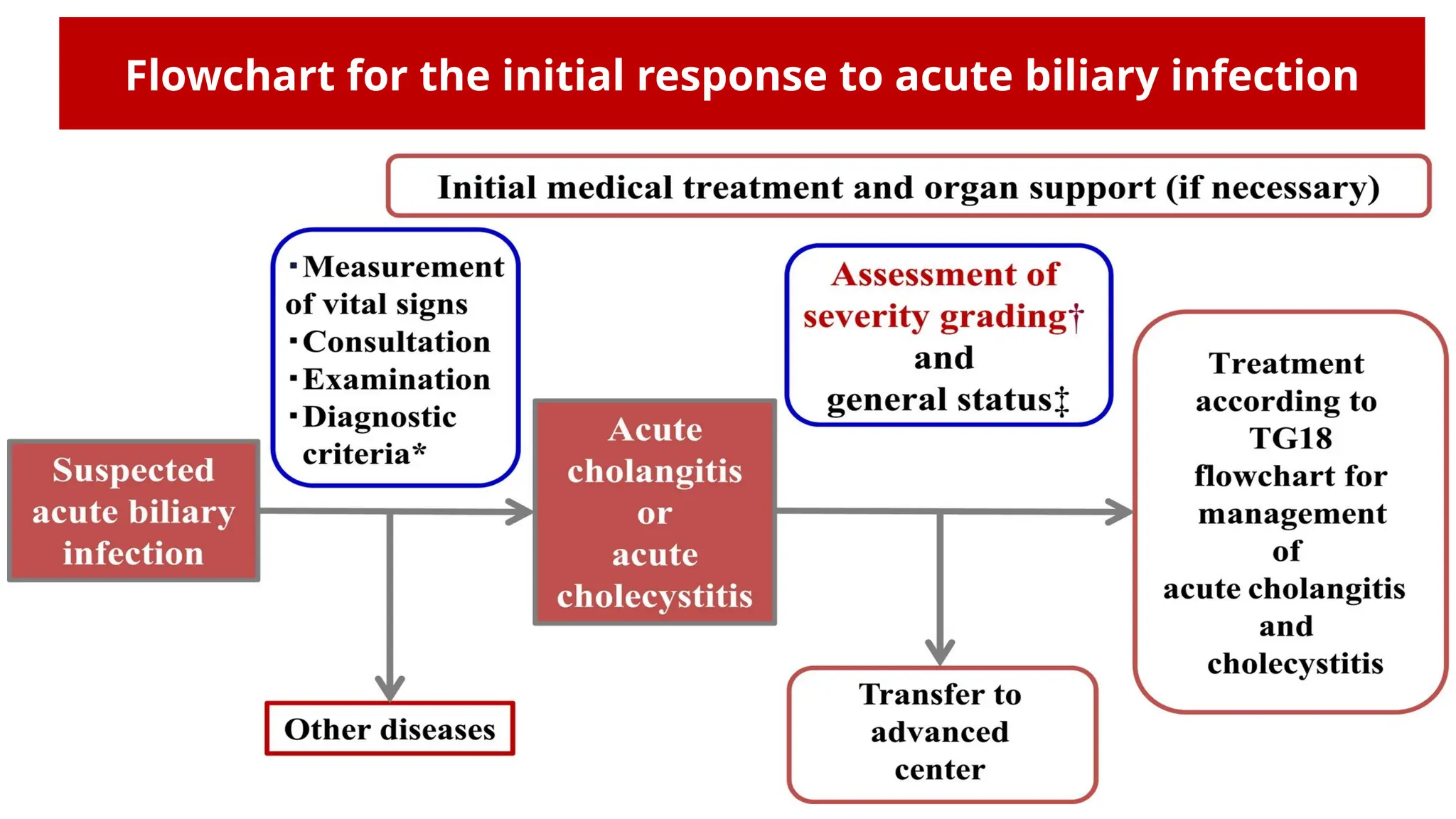

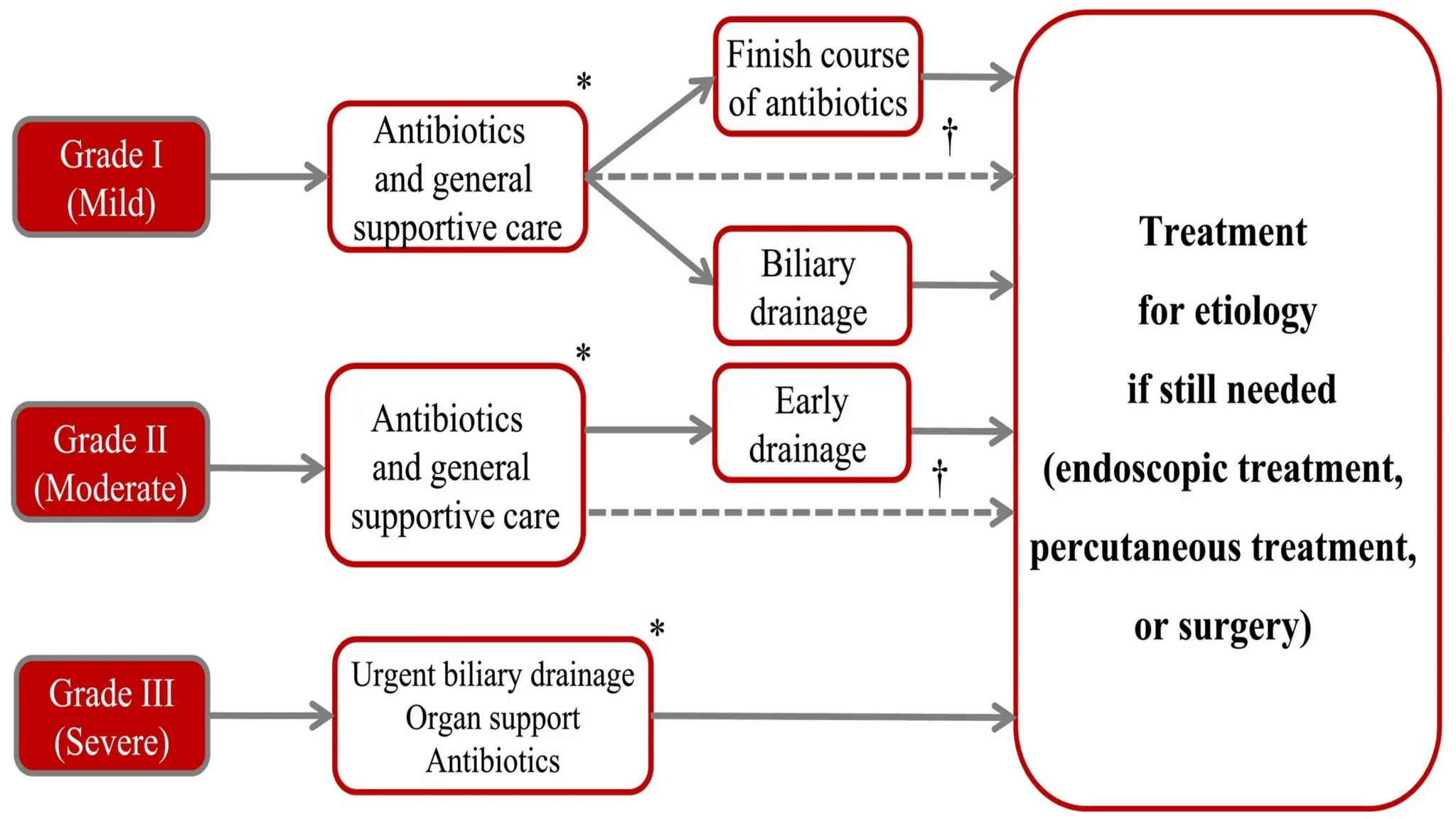

This document discusses acute cholangitis, an infection of the biliary tree often caused by enteric bacteria due to biliary stasis or obstruction, with specific diagnostic criteria and severity assessments based on recent guidelines. It highlights the various etiologies including gallstones, obstructive tumors, and procedural complications, along with recommended diagnostic tests such as ultrasound and MRI. Treatment strategies emphasize supportive care and timely biliary drainage, with the prognosis improving due to advancements in management practices.