This document presents a model for how integrins may initiate mechanotransduction signaling in osteocytes. Key points:

- Osteocytes are believed to sense mechanical loading in bone but require high strains for signaling, which tissue-level strains are too small to provide.

- The model proposes that osteocyte processes are attached to the bone canaliculi wall at discrete locations by β3 integrins. These integrin attachments act as focal adhesion complexes and amplify strains.

- Electron microscopy identified previously unrecognized projections from the canalicular wall that directly contact osteocyte processes, consistent with integrin attachments.

- A theoretical model was constructed to predict forces on the integrin attachments and resulting membrane strains, finding

![A model for the role of integrins in flow induced

mechanotransduction in osteocytes

Yilin Wang*, Laoise M. McNamara†, Mitchell B. Schaffler†, and Sheldon Weinbaum*‡

*Department of Biomedical Engineering, The City College of New York and the Graduate Center, City University of New York, New York, NY 10031;

and †Leni and Peter W. May Department of Orthopedics, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY 10029

Contributed by Sheldon Weinbaum, August 3, 2007 (sent for review May 14, 2007)

A fundamental paradox in bone mechanobiology is that tissue- initiating intracellular signaling was hard to identify because

level strains caused by human locomotion are too small to initi- none of the likely molecules in the tethering complex [i.e.,

ate intracellular signaling in osteocytes. A cellular-level strain- proteoglycans, hyaluronic acid, or CD44 (8, 10–12)] are known

amplification model previously has been proposed to explain this mediators of mechanically induced cell signaling. In this paper,

paradox. However, the molecular mechanism for initiating signal- we propose a paradigm for cellular-level strain amplification by

ing has eluded detection because none of the molecules in this integrin-based focal attachment complexes along osteocyte cell

previously proposed model are known mediators of intracellular processes.

signaling. In this paper, we explore a paradigm and quantitative Using an acrolein-paraformaldehyde-based fixation approach

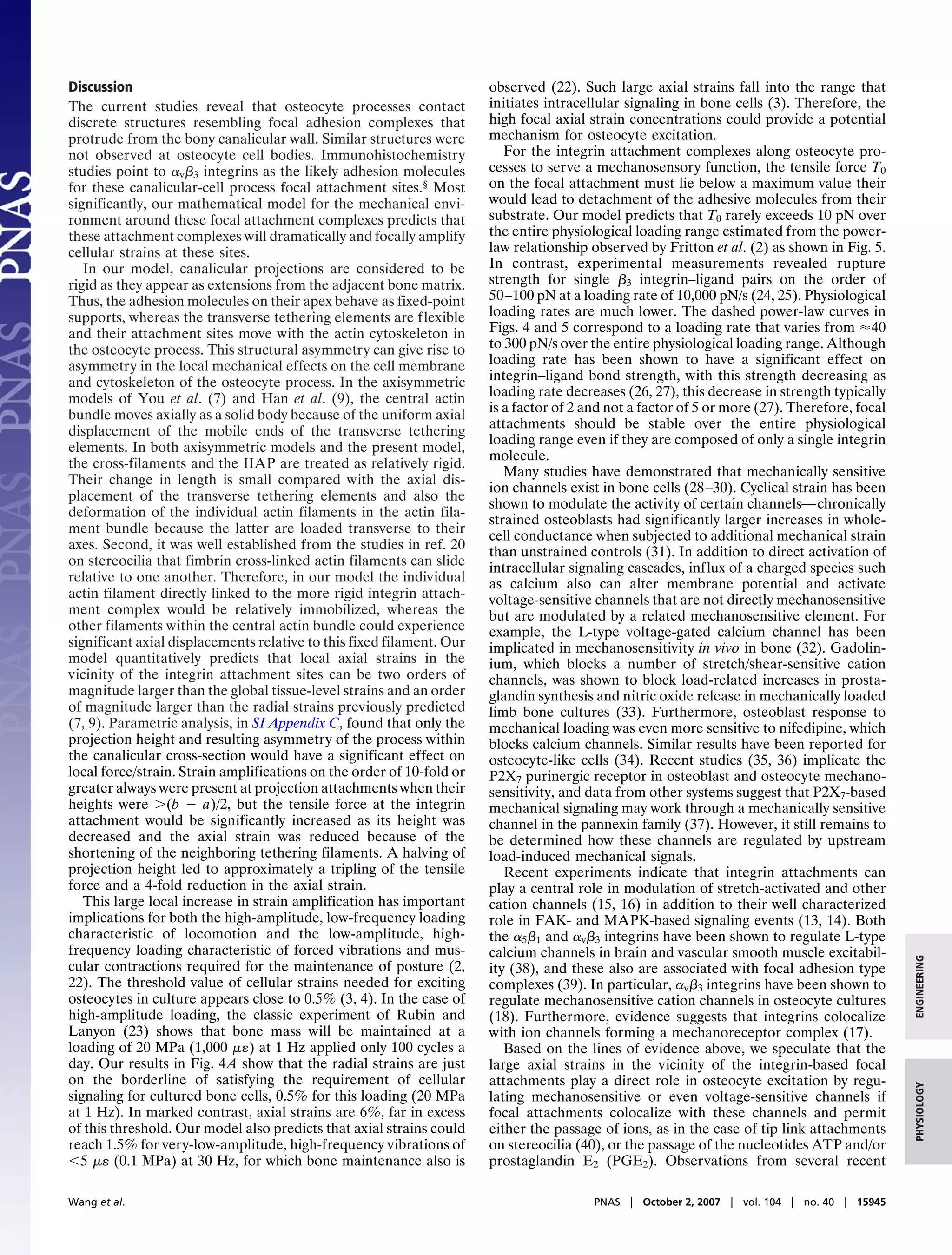

model for the initiation of intracellular signaling, namely that the for electron microscopy,§ we observed that discrete conical

processes are attached directly at discrete locations along the structures protrude periodically from the bony canalicular wall,

canalicular wall by 3 integrins at the apex of infrequent, previ- where they directly contact the cell membrane of the osteocyte

ously unrecognized canalicular projections. Unique rapid fixation process and, thus, resemble focal adhesion complexes (Fig. 1).

techniques have identified these projections and have shown them

Other studies pointed to ␣v3 integrins as the likely adhesion

to be consistent with other studies suggesting that the adhesion

molecules for these canalicular-cell process focal attachment

molecules are ␣v3 integrins. Our theoretical model predicts that

sites.§

the tensile forces acting on the integrins are <15 pN and thus

Integrins are transmembrane heterodimeric molecules com-

provide stable attachment for the range of physiological loadings.

posed of an ␣-subunit and a -subunit, and they anchor the cell’s

The model also predicts that axial strains caused by the sliding of

actin microfilaments about the fixed integrin attachments are an

cytoskeleton to the extracellular matrix molecules. More impor-

order of magnitude larger than the radial strains in the previously

tantly for understanding osteocyte mechanotransduction, inte-

proposed strain-amplification theory and two orders of magnitude grin focal adhesion complexes have been implicated as major

greater than whole-tissue strains. In vitro experiments indicated mechanical transducer sites in various other cells, initiating a

that membrane strains of this order are large enough to open host of intracellular signaling pathways, including focal adhesion

stretch-activated cation channels. kinase and small GTPases of the Ras family (13, 14). Further-

more, a growing body of evidence suggests that focal integrin

bone mechanotransduction ͉ integrin attachments ͉ osteocyte cell attachments are functionally and even structurally integrated

process ͉ strain amplification ͉ bone fluid flow with other putative membrane mechanotransducers, including

stress-activated ion channels in a range of cell types including

osteocytes (15–18).

A fundamental paradox in bone biology is that tissue-level

strains, which rarely exceed 0.1% in vivo (1, 2), are too small

to initiate intracellular signaling in bone cells in vitro (3, 4), where

Based on our in situ morphological studies, we herein con-

struct a model to quantitatively determine the mechanical

the necessary strains (typically 1.0%) would cause bone fracture. effects of focal attachment complexes on osteocyte cell pro-

Osteocytes, the most abundant cells in adult bone, are widely cesses. Specifically, we test the hypothesis that focal attachment

believed to be the primary sensory cells for mechanical loading complexes produce locally high strains along the cell membrane

because of their ubiquitous distribution throughout the bone of osteocyte processes. Our theoretical model provides the direct

tissue and their dendritic interconnections with both neighboring prediction of the piconewton-level forces on the focal attach-

osteocytes and osteoblasts (5, 6), but osteocytes also require high ments and the radial and axial membrane strains around these

local strains for mechanical stimulation. You et al. (7) developed attachment complexes as a function of loading magnitude and

an intuitive strain-amplification model to explain this paradox frequency. Axial membrane strains in the vicinity of the focal

wherein osteocyte processes are attached to the canalicular wall attachment sites can be an order of magnitude larger than the

by transverse tethering elements in the pericellular matrix. previously predicted radial strains generated by the transverse

According to this model, the drag generated by load-induced tethering elements (7, 9).

fluid flow through the pericellular matrix would create tensile

ENGINEERING

forces along the transverse elements supporting the pericellular

matrix. These resulting tensions then were transmitted by trans- Author contributions: M.B.S. and S.W. designed research; Y.W. and L.M.M. performed

research; M.B.S. and S.W. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; Y.W., M.B.S., and S.W.

membrane proteins to the central actin filament bundle in the analyzed data; and Y.W., M.B.S., and S.W. wrote the paper.

osteocyte cell process leading to circumferential expansion of The authors declare no conflict of interest.

the cell process. The basic structural features in this model, the

Abbreviation: IIAP, integrin intracellular anchoring protein.

transverse tethering elements, and the organization of the actin ‡To whom correspondence should be addressed at: Department of Biomedical Engineer-

filament bundle in the dendritic cell process were shown exper- ing, City College of New York, 138th Street at Convent Avenue, New York, NY 10031.

imentally by You et al. (8). The latter study also provided key E-mail: weinbaum@ccny.cuny.edu.

PHYSIOLOGY

input data for a greatly refined three-dimensional theoretical §McNamara, L. M., Majeska, R. J., Weinbaum, S., Friedrich, V., Schaffler, M. B. (2006) Trans.

model by Han et al. (9). Although both models elegantly showed Orthop. Res. Soc. 31:393 (abstr.).

that very small whole-tissue strains would be amplified 10-fold or This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/

more at the cellular level because of the tensile forces in the 0707246104/DC1.

transverse tethering elements, the molecular mechanism for © 2007 by The National Academy of Sciences of the USA

www.pnas.org͞cgi͞doi͞10.1073͞pnas.0707246104 PNAS ͉ October 2, 2007 ͉ vol. 104 ͉ no. 40 ͉ 15941–15946](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/amodelforflowinducedmechanotransduction-130303130916-phpapp02/75/A-model-for-flow-induced-mechanotransduction-1-2048.jpg)

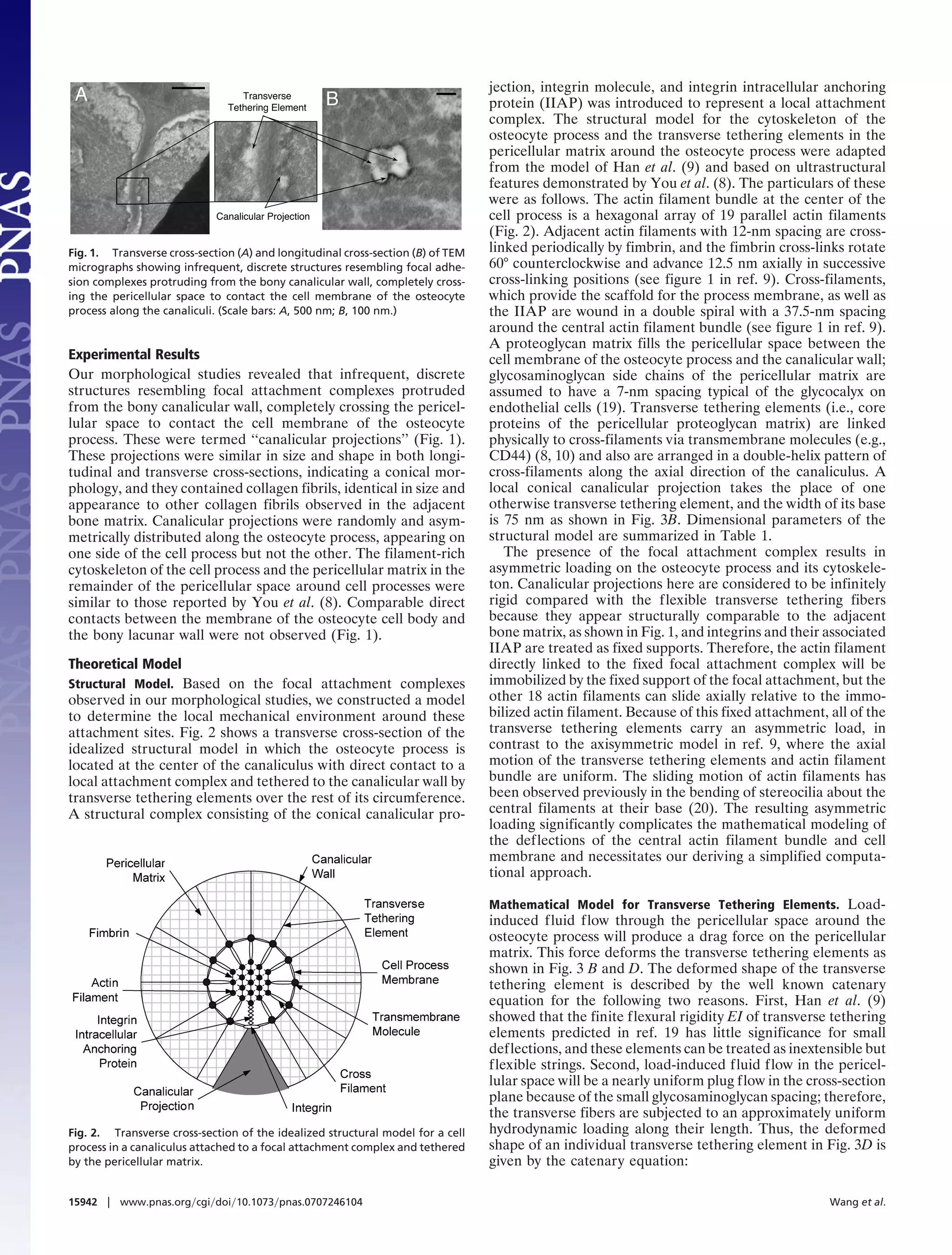

![bundle with its fimbrin cross-links in the core of the osteocyte

process is replaced by a homogenous cylindrical elastic structure

that has the same size and overall radial elastic modulus as the

original cross-linked structure. Han et al. (9) show that corner

and central actin filaments in the outer ring of the actin filament

bundle shown in Fig. 2 undergo different radial displacements

␦m1 and ␦m2, respectively, but that ␦m1 is Ϸ91% of ␦m2, and,

therefore, the difference is small enough to use an average value.

Second, the eleven transverse tethering elements and the focal

attachment shown in Fig. 2 are mathematically assumed to act in

the same cross-sectional plane when dealing with the overall

radial force balance as shown in Fig. 3A. As in ref. 9, it is

reasonable to assume that the deformations of these cross-

filaments and IIAP are substantially smaller than the bending

deformation of the actin filaments, which are loaded transverse

to their axes. Thus, the cross-filaments and IIAP are assumed not

to deform in the radial direction.

With these idealizations, one can reduce the complex struc-

tural geometry in Fig. 2 and its loading to a much simpler planar

loading configuration in which the osteocyte process is asym-

metrically located and loaded with a fixed focal attachment site

at point I at the apex of the canalicular projection, as sketched

in Fig. 3 A and B. Thus, the deformation induced by the tension,

Ti, is given by

␦i ϭ fTi ͑i ϭ 0,1,2, . . . , 6͒, [3]

Fig. 3. Deformation diagrams for the idealized mathematical model. (A)

Transverse cross-section of the idealized homogeneous elastic cylinder and where

the idealized plane for all of the transverse tethering elements and focal

attachment. (B) Longitudinal cross-section of the deformed transverse teth- 3

Lf

ering elements and sliding actin filaments. (C) Top view of the undeformed fϭ

and deformed cell process membrane around the focal attachment site (not to 340EIa

scale). (D) Force balance on a deformed transverse tethering element. The

dashed lines indicate the deformed structural elements. is the radial elastic modulus of the of the homogeneous cylin-

drical core [derived in supporting information (SI) Appendix A],

T0 is the tension associated with the focal attachment, T1–T6 are

wL

Tx

ϭ sinh

wd

Tx

ͩ ͪ

, [1]

the tensions on the transverse tethering elements, and the local

␦i are the deflections of the homogenous cylindrical core induced

by the Ti. Here, Lf is the length of one periodic unit shown in Fig.

where d is the radial distance between the canalicular wall and 3B, and EIa is the bending rigidity of a single actin filament in the

the cell process membrane, Tx is the constant radial component actin filament bundle of the osteocyte process.

of the tension on the transverse tethering element, and w is the The deformations ␦i (i ϭ 1, 2, . . . , 6) of the transverse

uniform hydrodynamic drag force per unit length of transverse tethering elements are derived in SI Appendix B. These defor-

tethering element. Because the canalicular projections are in- mations are related to the radial distances, di (i ϭ 1, 2, . . . , 6),

frequent and located at discrete locations along the canaliculi, between the canalicular wall and the deformed cell process

the majority of the pericellular space in the canaliculi can be membrane associated with individual transverse tethering

assumed to be of the same geometry as the model in ref. 9. elements:

Therefore, the pressure gradient along the cell process and the

drag force FD on the transverse tethering elements per unit ͱ3

d1 ϭ L Ϫ ␦1 ϩ ␦ 0; d2 ϭ L Ϫ ␦2 ϩ ␦0/2; d 3 ϭ L Ϫ ␦ 3;

length of cell process will be nearly the same as in ref. 9. w is 2

evaluated by dividing the total drag force on an axial periodic

unit of length Lf ϭ 37.5 nm in Fig. 3B by the total length of the [4A–C]

12 transverse tethering elements associated with the periodic ͱ3

unit and is given by d4 ϭ L Ϫ ␦4 Ϫ ␦0/2; d5 ϭ L Ϫ ␦5 Ϫ ␦0; d6 ϭ L Ϫ ␦6 Ϫ ␦0,

2

F DL f

wϭ

ENGINEERING

. [2] [4D–F]

12L

where L is the length of the transverse tethering element.

Here L is the length of each individual transverse tethering Because the tensions T0–T6 are assumed to act in the same

element, FD is the drag force on the transverse tethering plane, the overall force balance for T0–T6 sketched in Fig. 3A can

elements per unit length of cell process and is evaluated by the be expressed as

same expression as equation 8 in appendix A of ref. 9. The model

for the fluid flow through the pericellular matrix is based on the T0 ϩ ͱ3T1 ϩ T2 ϭ T4 ϩ ͱ3T5 ϩ T6. [5]

theoretical model in ref. 21.

PHYSIOLOGY

Eqs. 4A–F and 5 provide seven equations for the seven unknown

Mathematical Model for Osteocyte Cell Processes. Two mathemat- T0–T6, which are related to the displacements ␦0–␦6 through Eqs.

ical idealizations are introduced to simplify the analysis but 1 and 3.

retain the essential physics of the deformation for the central Because the free ends of the transverse tethering elements are

actin filaments shown in Fig. 2. First, the central actin filament displaced both radially and axially (i.e., in directions perpendic-

Wang et al. PNAS ͉ October 2, 2007 ͉ vol. 104 ͉ no. 40 ͉ 15943](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/amodelforflowinducedmechanotransduction-130303130916-phpapp02/75/A-model-for-flow-induced-mechanotransduction-3-2048.jpg)

![Table 1. Values of the parameters used in the model

A 1.5

Parameter Value 20 MPa, 1000 με

Osteonal hydrodynamic model (21, 45)

R adial Str ain ( % )

B, dimensionless relative compressibility 0.53 1.0

10 MPa, 500 με

of bone matrix to water

c, pore fluid pressure diffusion constant 0.13 5 MPa, 250 με

of the Biot theory, mm2/s 0.5

ro, radius of the osteon, m 100

1 MPa, 50 με

r1, radius of the osteonal lumen, m 27

Canaliculus and cell process (7, 8, 19)

0.0

b, radius of the canaliculus, nm 130

a, radius of the osteocyte process, nm 52 0 10 20 30 40

Frequency (Hz)

c, radius of the homogenous elastic 25

cylinder, nm

⌬, the spacing neighboring two 7

B 15

20 MPa, 1000 με

glycosaminoglycan chains, nm

Kp, Darcy’s permeability of matrix 10.3 10 MPa, 500 με

Ax ial Str a in ( % )

between cell process and canalicular 10

wall, nm2 5 MPa, 250 με

Ϫ2

, fluid viscosity, dyne*⅐s/cm2 10

Central actin bundle (7, 46) 5 1 MPa, 50 με

Lf, length of periodic fimbrin cross-over 37.5

along actin filament, nm 0.1 MPa, 5 με

Ela, bending rigidity of actin filaments, 1.5 ϫ 104

2 0

pN⅐nm

0 10 20 30 40

*1 dyne ϭ 10 N. Frequency (Hz)

Fig. 4. Membrane strains in the vicinity of focal attachment complex. (A) The

ular and parallel to the central line of the cell process), both the radial strain r (open arrow points to the radial strain on the cell process mem-

brane for an axisymmetric loading for a tissue loading of 10 MPa, from ref. 9). (B)

resulting radial and axial strain components on cell processes will

The axial strain a as a function of loading frequency with tissue-loading ampli-

be evaluated as a function of tissue loading. The radial strain r tude as a parameter. The dashed lines in both A and B show the physiological

in the plane through the focal attachment is defined as the ratio loadings of bone tissue based on the power-law relationship between strain

of the summation of deformations ␦0 and ␦6 to the undeformed amplitudes and loading frequencies observed by Fritton et al. (2).

diameter of the cell process membrane 2a in Fig. 3A, and is

given by

strains of 5 (0.1 MPa) at 30 Hz produce an axial strain around

r ϭ ͑␦0 ϩ ␦6͒/2a. [6] the focal attachment site of 1.5%.

In Fig. 5, we show the tensile force on the focal attachment,

The axial strain a in the vicinity of focal attachment site is T0, as a function of loading frequency up to 40 Hz with

defined as the relative change of the nonradial component of the tissue-loading amplitude as a parameter. T0 exhibits a monotonic

deformation of In (i.e., the deformation of the cell membrane of increase as loading frequency increases for a given tissue-loading

osteocyte process generated by the deformed transverse tether- amplitude. One observes that T0 is Ϸ10 pN at a physiological

ing element adjacent to the focal attachment) to its undeformed loading of 1,000 at 1 Hz.

length as shown in Fig. 3C and given by The dashed lines in Figs. 4 and 5 show the power-law

relationship between tissue-level strain amplitude and loading

a ϭ ͑InЈ r Ϫ Innr͒ ր Innr .

n [7] frequency derived from the whole-bone strain measurement by

Here InЈnr is the nonradial component of InЈ, the deformed state Fritton et al. (2).

of In, and Innr is the nonradial component of In.

40

Parameter Values. The values of the parameters used in the model,

which are grouped as parameters for the hydrodynamic model,

30 20 MPa, 1000 με

parameters for the canaliculus and cell process, and parameters

T ens ion ( pN)

for the central actin filament bundle, are shown in Table 1. 10 MPa, 500 με

20

Theoretical Results 5 MPa, 250 με

The radial strain r given by Eq. 6 and the axial strain a given

10 1 MPa, 50 με

by Eq. 7 are shown in Fig. 4 A and B, respectively, as a function

of loading frequency using tissue-loading amplitude as a param-

eter. For comparison, radial strain in the cell process membrane 0

for axisymmetric loading from ref. 9 for a tissue loading of 10 0 10 20 30 40

MPa is shown in Fig. 4A, open arrow. Radial strains predicted Frequency (Hz)

by the current model are Ϸ70% of those in Han et al. (9).

Fig. 5. The tension on the focal attachment T0 as a function of loading

Strikingly, a is approximately one order of magnitude larger frequency with tissue-loading amplitude as a parameter. [The dashed line

than r for the same tissue loading. a is predicted to be Ϸ6% at shows the physiological loadings of bone tissue based on the power-law

a physiological loading of 20 MPa at 1 Hz and can exceed 1% for relationship between strain amplitudes and loading frequencies observed by

low-amplitude, high-frequency tissue loadings, e.g., small tissue Fritton et al. (2).]

15944 ͉ www.pnas.org͞cgi͞doi͞10.1073͞pnas.0707246104 Wang et al.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/amodelforflowinducedmechanotransduction-130303130916-phpapp02/75/A-model-for-flow-induced-mechanotransduction-4-2048.jpg)