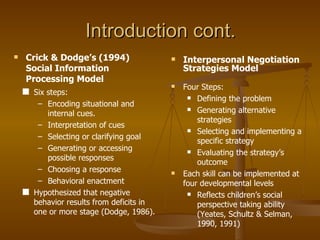

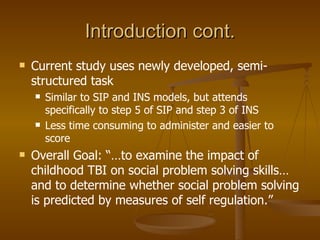

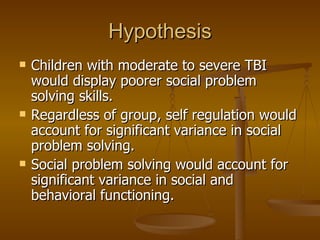

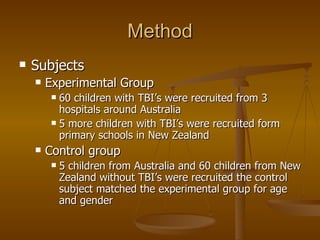

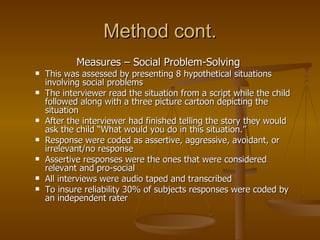

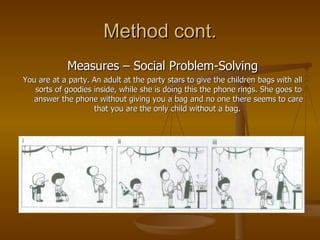

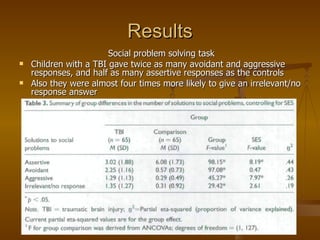

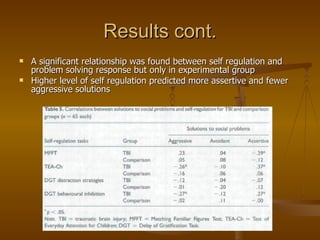

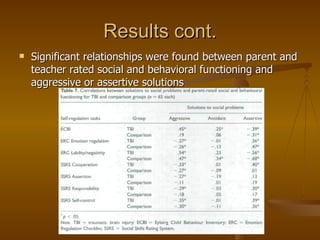

The study examined the association between social problem solving skills, self-regulation, and social/behavioral functioning in children with moderate to severe traumatic brain injuries compared to children without brain injuries. Children with brain injuries provided fewer assertive and more avoidant/aggressive responses to social problem solving scenarios. Higher self-regulation predicted more assertive responses. Social problem solving responses accounted for variance in social/behavioral functioning ratings, with aggressive responses associated with poorer functioning and assertive responses associated with better functioning.