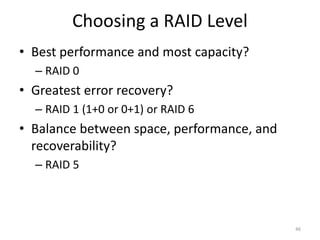

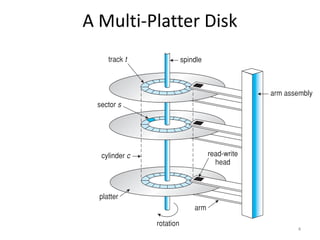

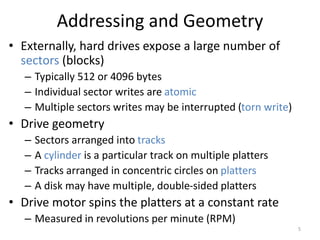

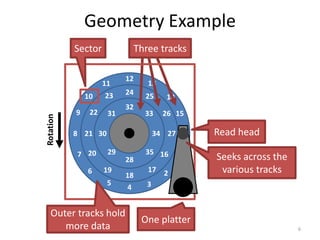

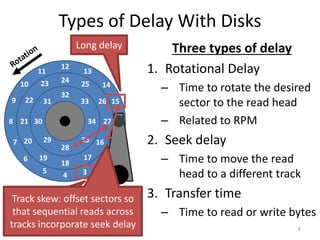

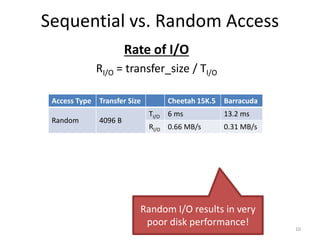

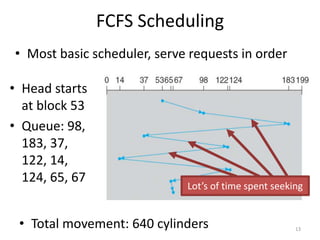

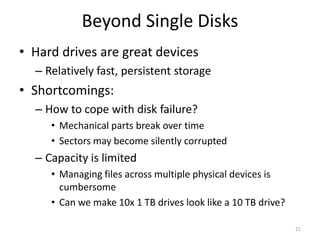

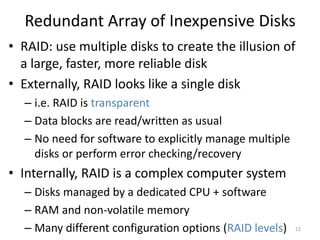

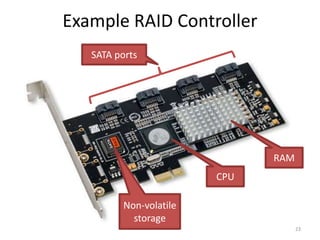

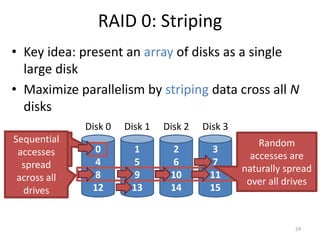

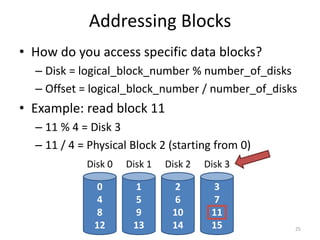

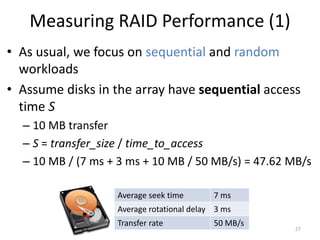

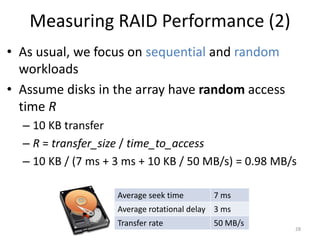

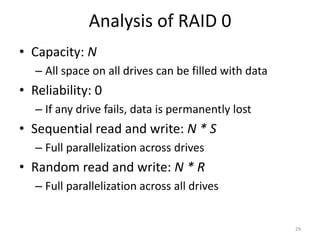

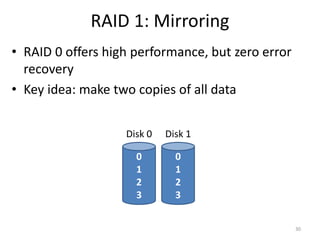

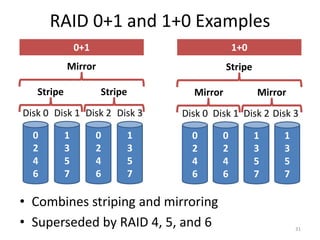

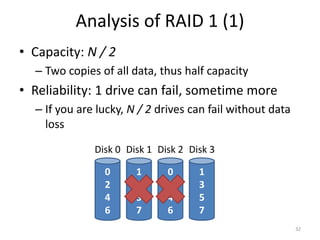

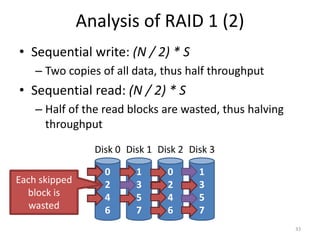

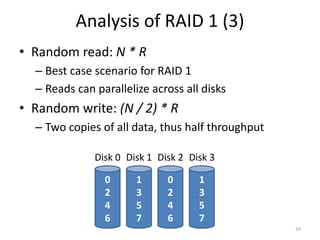

Hard drives store data on spinning platters, with sectors arranged in concentric tracks. RAID arrays distribute data across multiple disks for increased capacity, performance, and reliability. RAID levels 0 and 1 provide different tradeoffs - RAID 0 uses striping for higher performance but no redundancy, while RAID 1 uses mirroring to allow any single disk failure but halves write performance and capacity. Proper scheduling of read/write requests can improve disk performance under different access patterns like sequential versus random.

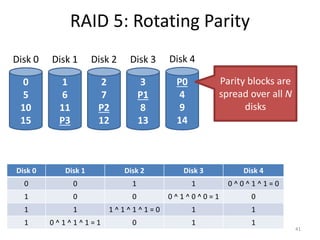

![Analysis of Raid 5

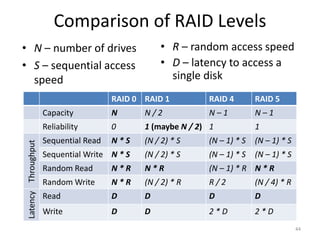

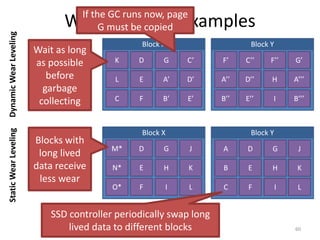

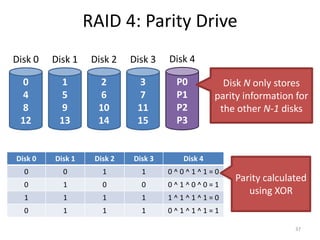

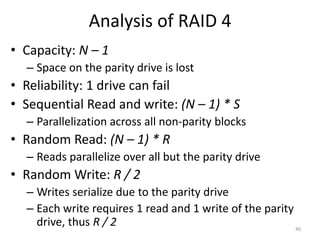

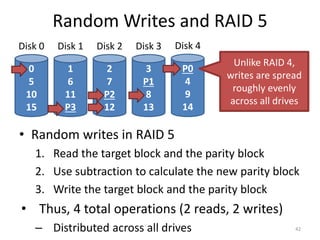

• Capacity: N – 1 [same as RAID 4]

• Reliability: 1 drive can fail [same as RAID 4]

• Sequential Read and write: (N – 1) * S [same]

– Parallelization across all non-parity blocks

• Random Read: N * R [vs. (N – 1) * R]

– Unlike RAID 4, reads parallelize over all drives

• Random Write: N / 4 * R [vs. R / 2 for RAID 4]

– Unlike RAID 4, writes parallelize over all drives

– Each write requires 2 reads and 2 write, hence N / 4

43](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/9storagedevices-231024114801-a3fafcff/85/9_Storage_Devices-pptx-43-320.jpg)