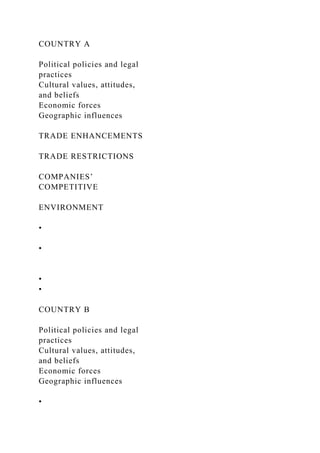

Chapter 6 of 'International Business Environments and Operations' discusses trade protectionism, outlining governmental policies aimed at enhancing or restricting trade. It elaborates on the economic and noneconomic rationales for intervention, the conflicting pressures from interest groups, and the complexities of trade policy outcomes. Furthermore, it illustrates the instruments of trade control, including tariffs and nontariff barriers, as well as the impact of these policies on business opportunities and uncertainties.

![•

•

•

GLOBAL SUPPLY MANAGEMENT FORUM

CASE: GS-34

DATE: 9/27/04 (REV’D. 04/07/05)

Lyn Denend prepared this case under the supervision of

Professor Hau Lee as the basis for class discussion rather than

to

illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an

administrative situation.

Copyright © 2004 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland

Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. To order

copies or

request permission to reproduce materials, e-mail the Case

Writing Office at: [email protected] or write: Case Writing

Office, Stanford Graduate School of Business, 518 Memorial

Way, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305-5015. No part

of

this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system,

used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any

means –– electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or

otherwise –– without the permission of the Stanford Graduate](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/6-internationalbusinessenvironmentsoperations-221224072054-11d6ae57/85/6-International-BusinessEnvironments-Operations-docx-18-320.jpg)