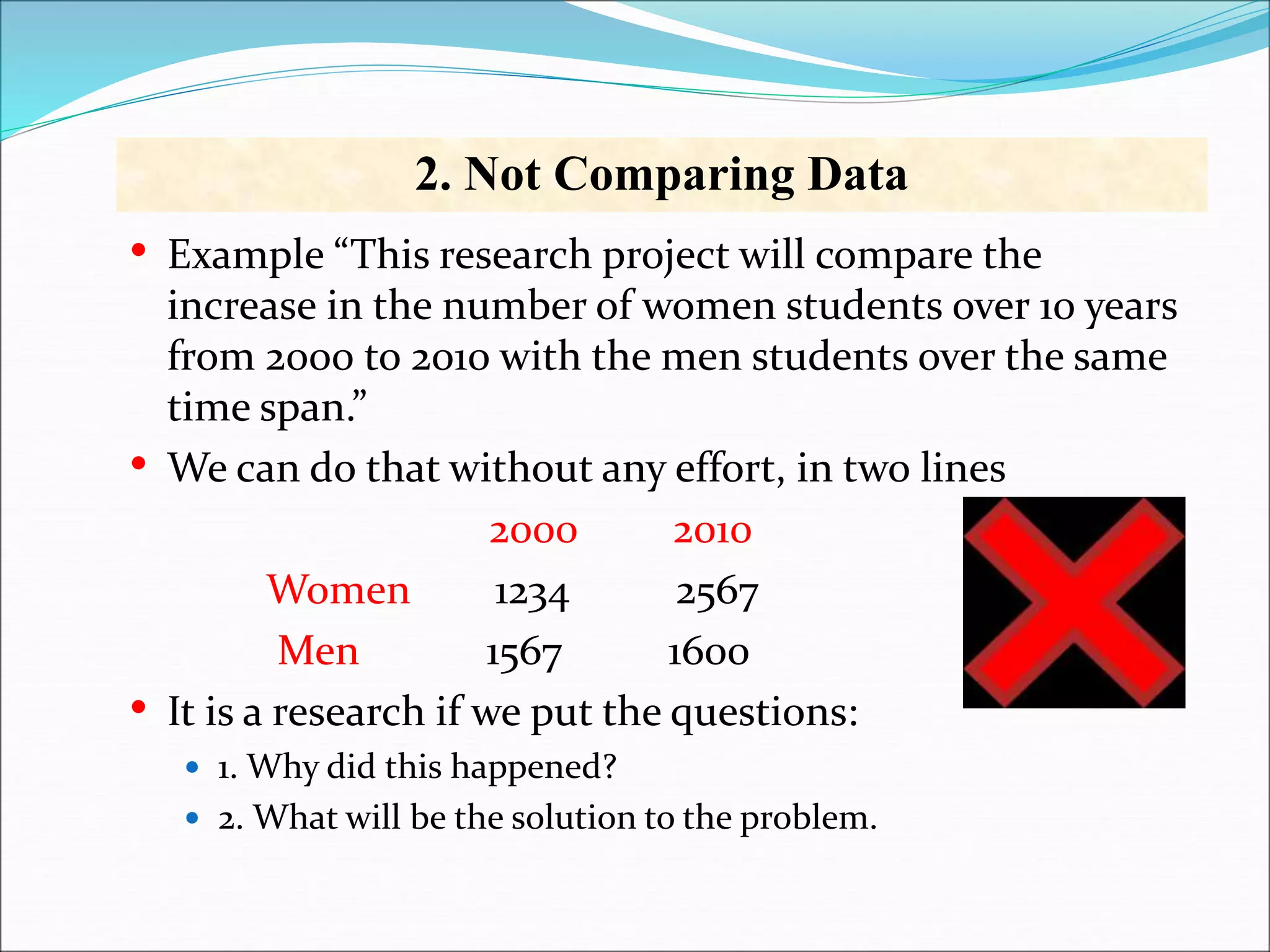

This document discusses defining and justifying a research problem. It begins by defining what constitutes a research problem and provides examples of problems that are and are not suitable for research. It outlines criteria for selecting a good research problem, such as having interest in the problem area and the problem enhancing knowledge. The document provides guidance on justifying a research problem through literature review and discussing it with experts. It also discusses formulating the problem statement, identifying subproblems, and proposing hypotheses as potential solutions to guide the research.