The document discusses decidability and defines key concepts such as:

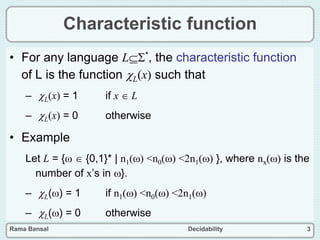

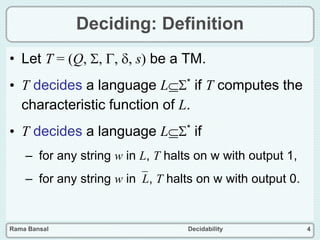

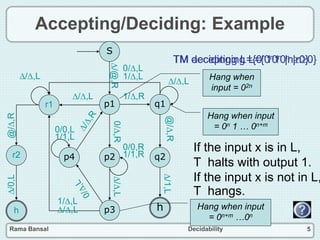

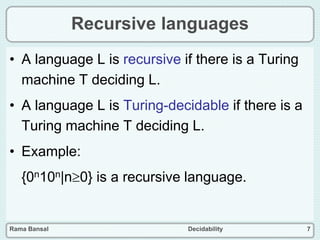

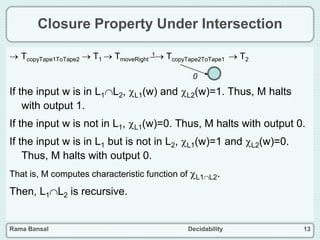

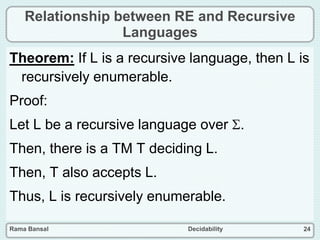

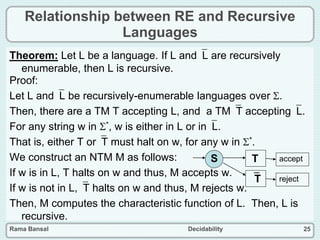

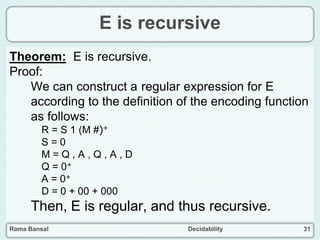

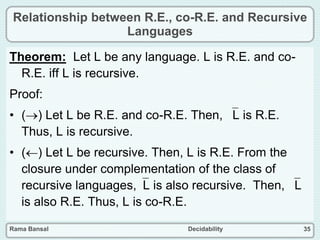

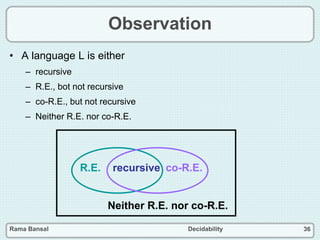

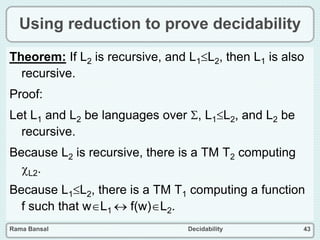

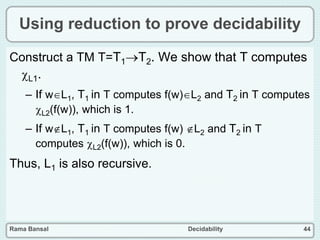

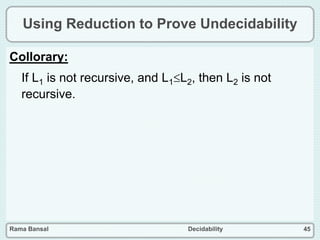

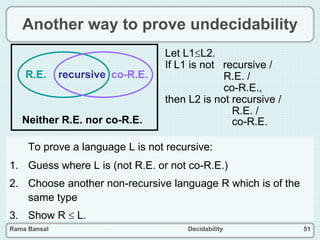

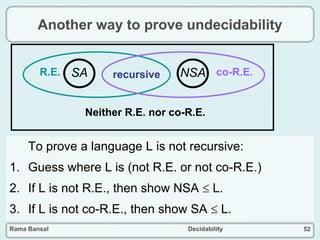

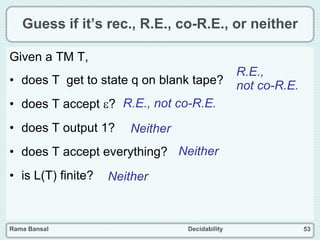

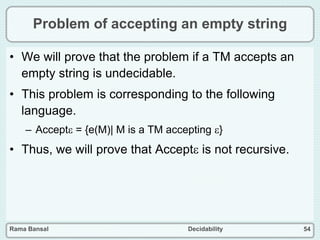

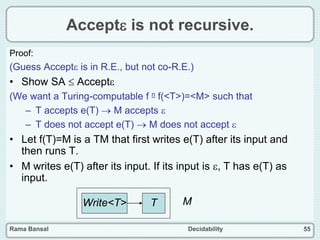

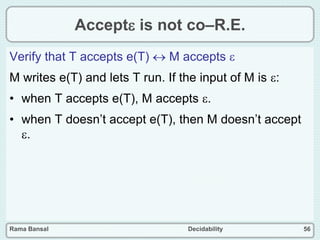

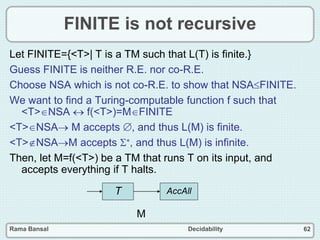

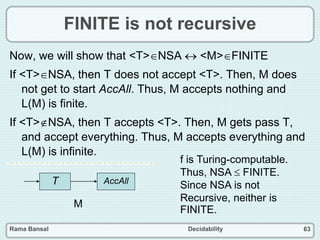

- A language is decidable if there is a Turing machine that can decide its characteristic function.

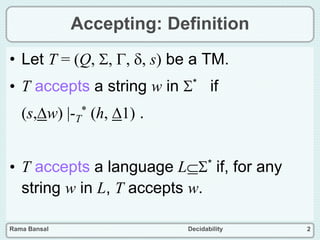

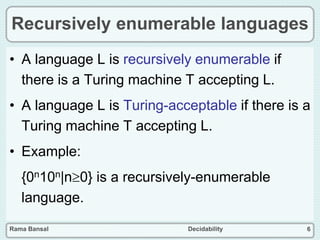

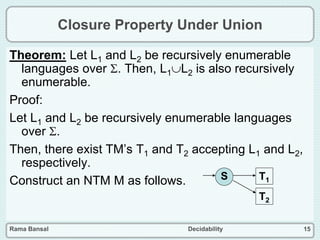

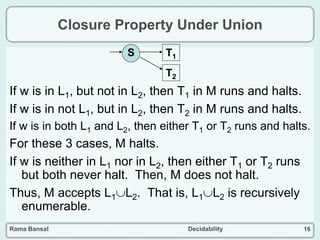

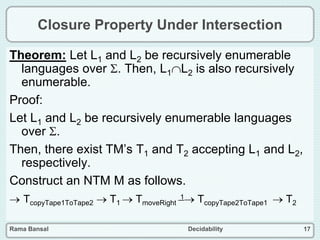

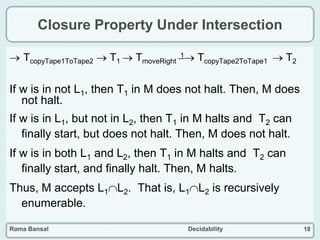

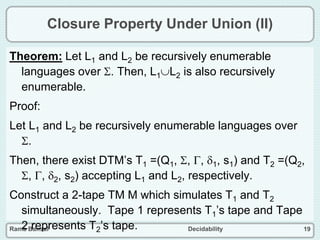

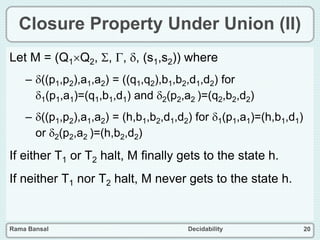

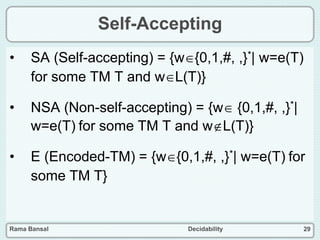

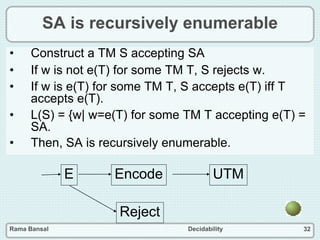

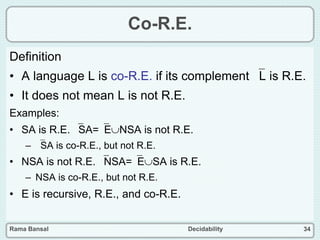

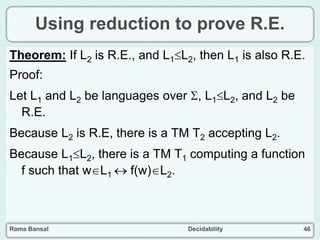

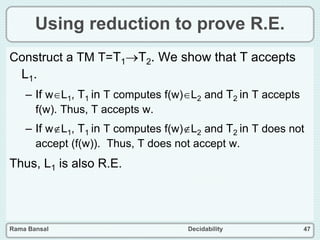

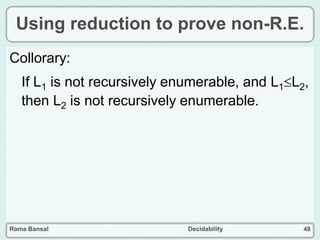

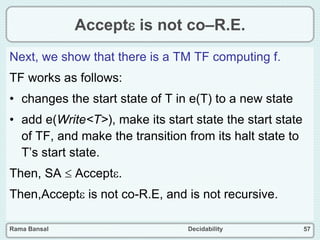

- A language is recursively enumerable if there is a Turing machine that can accept it.

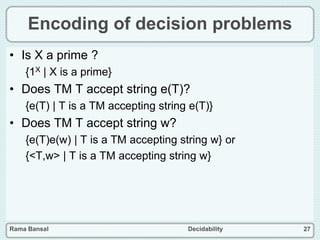

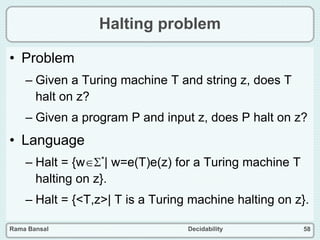

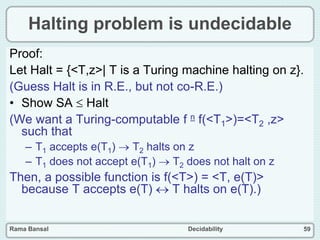

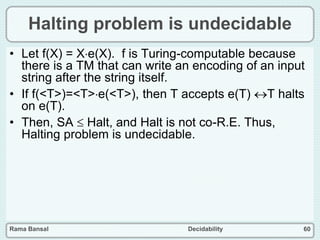

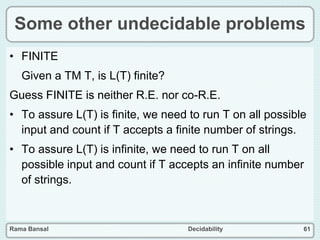

- The halting problem, which asks whether a Turing machine will halt on a given input, is undecidable.

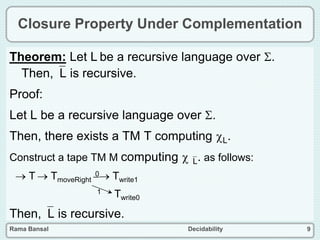

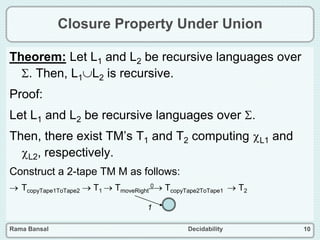

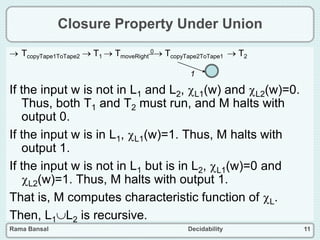

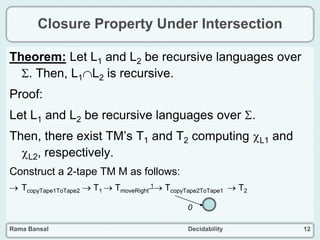

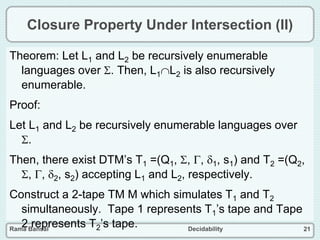

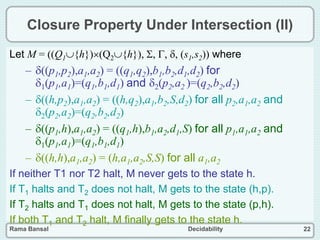

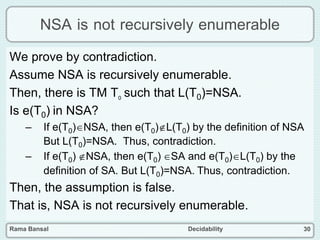

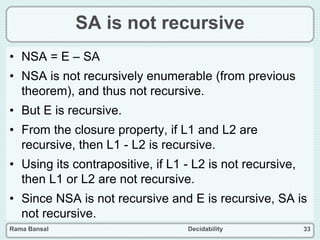

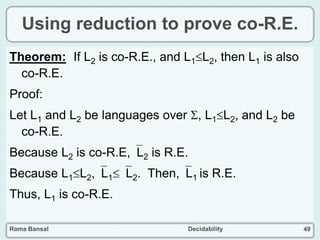

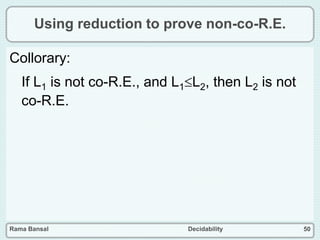

- Closure properties are discussed, showing that the classes of recursive and recursively enumerable languages are closed under union, intersection, and complement.